Different Leaves from Dunk Island: the Banfields, Dorothy Cottrell and the Singing Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drivenow Suggested Iternary

Brisbane to Cairns 10 day Suggested Itinerary Day 1. Brisbane to Noosa Collect your campervan today. Allow at least 1-1.5 hours so that you are familiar with the vehicle before leaving the depot. Depart Perth and head north for Noosa. The seaside town offers many boutique shops, white beaches with crystal-clear waters and world class restaurants. Before reaching Noosa, just outside of Caloundra is the famous Australia Zoo, which used to be home to the legendary crocodile hunter Steve Irwin. Distance: 145kms, 2 hours Stay: Two nights at Noosa Bougainvillia Holiday Park Day 2. Noosa There are many day trips you can do from Noosa. Montville is a must-see on your campervan travels. Approximately one hour south-west of Noosa, Montville is home to the best fudge in Queensland and offers quaint markets on weekends, amazing walking tracks, a cheese factory and a number of wineries. The small town of Eumundi, located approximately 30 minutes north-west of Noosa, hosts one of the largest markets on the Coast. The Eumundi Markets are held every Wednesday and Saturday. Or if you aren’t up for a spot of shopping Noosa has some amazing beaches! Day 3. Noosa to Hervey Bay Today say goodbye to the beautiful Noosa and travel to Hervey Bay. If you every wanted to go whale watching and see the magnificent humpback whales come out to play, then Hervey Bay is the place. The season runs from mid-July to early November every year and is a must if you are in the area. -

Great Keppel Island Resort Project

Great Keppel Island Resort project Coordinator-General’s report on the environmental impact statement March 2013 © State of Queensland. Published by Queensland Government, March 2013, 63 George Street, Brisbane Qld 4000. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this publication. The State of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Copyright inquiries about this publication should be directed to [email protected] or in writing to: Administrator (Crown Copyright and Other IP), Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning, PO Box 15517, City East, Qld 4002. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone the Queensland Department of State Development, Infrastructure and Planning on 132 523. Disclaimer: This report contains factual data, analysis, opinion and references to legislation. The Coordinator-General and the State of Queensland make no representations and give no warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose of such data, analysis, opinion or references. You should make your own enquiries and take appropriate advice on such matters. Neither the Coordinator-General nor the State of Queensland will be responsible for any loss or damage (including consequential loss) you may suffer from using or relying upon the content of this report. -

Discovering the Family Islands Book

! ! ! ! ! ! ! Discovering!the! ! ! FAMILY!ISLANDS! ! ! ! ! A guide to the Bedarra and Dunk Island group, ! North Queensland ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! v! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Other books by James Porter Fiction The Swiflet Isles Warri of the Wind The Kumul Feathers Hapkas Girl The Sacred Tree Non-fiction Discovering Magnetic Island Further Confessions of the Beachcomber (E. J. Banfield collection) Beachcomber’s Paradise (E. J. Banfield collection) vi vii Acknowledgements Contents The quotations from Captain Cook’s journals were obtained from the Dr J. C. Beaglehole edited version, The Journals of Captain James Cook on his voyage of discovery, Volume 1. Other references include E. J. Banfield’s books: Confessions of a Beachcomber, My Tropic Isle, Tropic Days, and Last Leaves from Dunk Island; a booklet Clump Point and District by Miss Constance Mackness, M.B.E.; and the Cardwell Shire Story by Dorothy Jones. Noel Wood of Bedarra Island kindly supplied much of the information about settlers on the islands after Banfield. Dr Betsy R. Jackes of the School of Biological Sciences at the James Cook University of North Queensland, Townsville, corrected many of the botanical plant names which have changed since Banfield’s time. Chris Dickson of Bedarra was most helpful while I was researching material on the islands. Sketches are by Kathryn Kerswell, maps and photographs are mainly my own. James G. Porter Preface x Discovery 1 Geography 8 E. J. Banfield 21 First published in 1983 by Another Beachcomber and Island Settlers 29 Kullari Publications The Plants 52 P.O. Box 477 Birds 62 Lutwyche, Qld 4030 Marine Life 75 Access Reprinted 1985 © James G. -

Coastal Queensland & the Great Barrier Reef

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Coastal Queensland & the Great Barrier Reef Cairns & the Daintree Rainforest p228 Townsville to Mission Beach p207 Whitsunday Coast p181 Capricorn Coast & the Southern Reef Islands p167 Fraser Island & the Fraser Coast p147 Noosa & the Sunshine Coast p124 Brisbane ^# & Around The Gold Coast p107 p50 Paul Harding, Cristian Bonetto, Charles Rawlings-Way, Tamara Sheward, Tom Spurling, Donna Wheeler PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Coastal BRISBANE FRASER ISLAND Queensland . 4 & AROUND . 50 & THE FRASER Coastal Queensland Brisbane. 52 COAST . 147 Map . 6 Redcliffe ................94 Hervey Bay ............149 Coastal Queensland’s Manly Rainbow Beach .........154 Top 15 . 8 & St Helena Island .......95 Maryborough ..........156 Need to Know . 16 North Stradbroke Island ..96 Gympie ................157 What’s New . 18 Moreton Island ..........99 Childers ...............157 If You Like… . 19 Granite Belt ............100 Burrum Coast National Park ..........158 Month by Month . 21 Toowoomba ............103 Around Toowoomba .....106 Bundaberg .............159 Itineraries . 25 Bargara ............... 161 Your Reef Trip . 29 THE GOLD COAST . .. 107 Fraser Island ........... 161 Queensland Outdoors . 35 Surfers Paradise ........109 Travel with Children . 43 Main Beach & The Spit .. 113 CAPRICORN COAST & Regions at a Glance . 46 Broadbeach, Mermaid THE SOUTHERN & Nobby Beach ......... 115 REEF ISLANDS . 167 MATT MUNRO / LONELY PLANET IMAGES © IMAGES PLANET LONELY / MUNRO MATT Burleigh Heads ......... 116 Agnes Water Currumbin & Town of 1770 .........169 & Palm Beach .......... 119 Eurimbula & Deepwater Coolangatta ............120 National Parks ..........171 Gold Coast Hinterland . 122 Gladstone ..............171 Tamborine Mountain ....122 Southern Reef Islands ...173 Lamington Rockhampton & Around . 174 National Park ..........123 Yeppoon ...............176 Springbrook Great Keppel Island .....178 National Park ..........123 Capricorn Hinterland ....179 DINGO, FRASER ISLAND P166 NOOSA & THE WHITSUNDAY SUNSHINE COAST . -

The Title Page of E.J. Banfield's the Confessions of a Beach

H.P. HESELTINE THE CONFESSIONS OF A BEACHCOMBER The title page of E.J. Banfield's The Confessions of a Beach- comber bears this quotation from Thoreau: If a man does not keep pace with his companions perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears. We have it on the authority of the naturalist Charles Barrett' that this was Banfield's favourite quotation from the American writer. Indeed, the range and number of his quotations from Thoreau's books suggest that the lord of Dunk Isle had a deeply familiar admiration for the hermit of Concord. Two chapters of Banfield's second book, My Tropic Isle (1911),2 for instance, carry epigraphs from Thoreau. Chapter V, "Silences," is headed, thus, by the quotation, "Who has not hearkened to her [Nature's] infinite din?" Chapter VI, devoted to "Fruits and Scents," establishes its theme through Thoreau's phrase, "The pot herb of the gods." There are more than specific echoes of Thoreau in Banfield's prose. The whole of the Con- fessions is structured on much the same lines as Walden: in each book, opening chapters which give some account of the back- ground to and motives for the writer's retreat from society, are followed by descriptions, varying from the lyrical to the virtu- ally statistical, of the surroundings where he makes his new life. Such explicit borrowings and analogies of structure seem to invite a comparison between Banfield and Thoreau, between Dunk Island and Walden Pond (between Townsvile and Con- cord even?) as a profitable way into something like an exact understanding of the Australian writer's achievement. -

The History of Green Island

91 THE HISTORY OF GREEN ISLAND By DOROTHY JONES Read at a Meeting of the Society on 24 June 1976 Introduction — I have chosen to present this paper, on the occasion of the centenary year of Cairns, on the history of probably its most familiar area, Green Island. 1 do this because the broad history of Cairns itself is already well known in the Society's papers through the researches of the late Mr. J. W. Collinson. Green Island, about 34 acres in extent, lies some 16 miles due east of Cairns. Low and sandy, it is virtually a wooded sand cay surrounded by coral reefs. On Trinity Sunday, 1770, Captain Cook anchored the Endeavour in Mission Bay to look for water, the third landing he had made in what was to be the Colony of Queensland. From this anchorage a "low green woody island" bore 35 deg. E, which he named Green Island. Generally accepted that the naming was to honour the 'Endeavour's'' astronomer, 1 have found only the patently descriptive reference given. Green Island with its dangers of reef and shoal, flat profUe and obvious sand cay characteristics deserved and received no attention from mariners in transit, official or otherwise, who confined their activities to nearby Fitzroy Island with its mainland characteristics and, more importantly, easily accessible fresh water. After settlement began in the far north Green Island was well known to the captains of the small ships of the sixties sailing a hazardous course out of Bowen through Cleveland Bay, Cardwell and Somerset to Gulf ports, or on a commercial venture in search of sandalwood, pearling or beche de mer grounds. -

Hamilton Island

ISLAND getaways HAMILTON ISLAND Perfectly situated on the edge of the Great Barrier Reef, amongst Queensland’s 74 Whitsunday Islands, Hamilton Island offers an experience like no other: glorious weather, Arafura Torres Strait azure waters, brilliant beaches, awe-inspiring coral reefs, fascinating fl ora and fauna, fi ne Sea Timor DARWIN Kakadu Sea National Park Gulf of Carpentaria GREAT KATHERINE Cape York LIZARD ISLAND Peninsula food and wines, and activities almost too numerous to mention. BAR COOKTOWN RI Kimberley ER Purnululu Cape National Park Tribulation PORT DOUGLAS Coral (Bungle Bungle Ranges) HALLS CAIRNS CREEK Sea BROOME Geikie Gorge DUNK ISLAND National Park NORTHERN REEF TERRITORY MARI TOWNSVILLE NE AIRLIE HAYMAN Mt Isa ISLAND WHITSUNDAY BEACH GROUP HAMILTON PARK ISLAND The Ghan QUEENSLAND EXMOUTH Ningaloo ALICE SPRINGS Reef KINGS HERON WESTERN CANYON ISLAND AUSTRALIA AYERS ROCK/ULURU FRASER ISLAND WARBURTON MONKEY MIA NOOSA Sunshine SOUTH AUSTRALIA Coas t BRISBANE COOBER SURFERS PARADISE Indian Indian Pacific PEDY Gold Coas t Ocean Nullarbor Plain KALGOORLIE WILPENA POUND NEW COFFS HARBOUR SOUTH PERTH Great Australian Flinders Ranges WALES Bight Hunter Barossa Valley Valley Blue Mountains ADELAIDE MARGARET RIVER SYDNEY ALBANY CANBERRA KANGAROO South Pacific ISLAND VICTORIA Southern Ocean Ocean MELBOURNE Great Ocean BLUE MOUNTAINS Road PHILLIP HUNTER VALLEY ISLAND Bass Strait Tasm an Sea Cradle Mt-L St Clair LAUNCESTON National Park TASMANIA HOBART Short on time? Fly direct from Sydney, Brisbane or Melbourne to Hamilton Island to make the most of your time in the Whitsundays. REEF VIEW HOTEL The views of Catseye Bay from the coral sea rooms are amongst the best in the world. -

Shark Control Records Hindcast Serious Decline in Dugong Numbers Off the Urban Coast of Queensland Dugong Distribution and Abund

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARlNE PARK AuTIiOkIT'i RESEARCH PUBLICATION NO. 70 Shark Control Records Hindcast Serious Decline in Dugong Numbers off the Urban Coast of Queensland Helene Marsh, Glenn De'ath, Neil Gribble and Baden Lane AND Dugong Distribution and Abundance in the Southern Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and Hervey Bay: Results of an Aerial Survey in October-December 1999 RCSEARCH PUBLICATION NO. 70 I lVIl ! *" Shark Control Records Hindcast Serious Decline in Dugong Numbers off the Urban Coast of Queensland Helene Mar~Ii'. Glenn De'alh', Neil Gribblc2 >lnd Bad{."fl L:lndl 'ScIIOU1 <>I 1""",">lII:."".",.._ <;tw- ,"oO !JIIoIlr"l'lTY. J.",,,,, (;<><>1< U,,,,,,,,~, fow...._ 01<1 ~a II........,,.;,,, "Nor'h.." r_ ~~r., PO 110' 53'l'I!. C>o1"s. UId 4810. _ ..Iio, ~.J.yI(j 9No1< Con,'Ol 0,.",--. M'~ H<oJ<c, Gox-?< S..-w, Bre./;<lno,) 00J .cw. Au-..lr."" ••U.:.:••••_I.:1.'\' Dugong Distribution and Abundance in the Southern Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and Hervey Bay: Results of an Aerial Survey in October-December 1999 Helene Marsh and Ivan Lawler GIUAT•IlAilRJER REEF 1'0 tl<>. 1319 TOWf>~yi~o 01<1 481 0 TelepOO<1e: (01) 4'50 0100 Fo.: (07) 4112 8093 Fmall: INFOO(Jbm1l>.',go"."" www.!lbt"mlJlO.go•...., © Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority/James Cook University 2001 ISSN 1037-1508 ISBN 0 642 23099 4 Published August 2001 by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. -

Pesticide Monitoring in Inshore Waters of the Great

Pesticide monitoring in inshore waters of the Great Barrier Reef using both time-integrated and event monitoring techniques (2012 - 2013) September 2013 Prepared for – The Program Manager, The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority PESTICIDES - INSHORE MARINE WATER QUALITY MONITORING & TERRESTRIAL RUN-OFF – DRAFT REPORT 2011-2012 Project Teams – Inshore Marine Water Quality Monitoring Christie Gallen1, Chris Paxman1, Andrew Banks1, Jochen Mueller1 Assessment of Terrestrial Run-off Entering the Reef Christie Gallen1, Chris Paxman1, Jochen Mueller1, Eduardo Da Silva2, Amelia Wengner2, Caroline Petus2, Michelle Devlin2 1The University of Queensland, The National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology (Entox) 2Australian Centre for Tropical and Freshwater Research (ACTFR), Catchment to Reef Research Group, James Cook University Report should be cited as – Gallen, C., Devlin, M., Paxman, C., Banks, A., Mueller, J. (2013) Pesticide monitoring in inshore waters of the Great Barrier Reef using both time-integrated and event monitoring techniques (2012 - 2013). The University of Queensland, The National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology (Entox). Direct Enquiries to – Professor Jochen Mueller Phone: +61 7 3000 9197 Fax: +61 7 3274 9003 Email: [email protected] Web: Entox Homepage The University of Queensland The National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology (Entox) 39 Kessels Rd Coopers Plains QLD 4108 i National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology Entox is a joint venture between The University of Queensland and Queensland Health PESTICIDES - INSHORE MARINE WATER QUALITY MONITORING & TERRESTRIAL RUN-OFF – DRAFT REPORT 2011-2012 Acknowledgements Other contributors to this work include- Carol Honchin of the GBRMPA for her work on the PSII-HEq Index in 2010. -

1998 ANNUAL REPORT1998 ANNUAL 1998 Annual Report Brought to You by Global Reports 1998 Annual Report

1998 ANNUAL REPORT 1998 Annual Report Brought to you by Global Reports 1998 Annual Report Registered Office Financial Calendar Notice of Meeting Qantas Airways Limited 1998 The Annual General Meeting of ACN 009 661 901 30 June Year end Qantas Airways Limited will be held Qantas Centre 20 August Preliminary final result at 2:00 pm on Wednesday Level 9 Building A announcement 18 November 1998 in the 203 Coward Street 4 November Record date for final Grand Ballroom at the Mascot NSW 2020 dividend Sheraton Brisbane Hotel & Towers, Australia 18 November Annual General Meeting 249 Turbot Street, Brisbane. Telephone 61 2 9691 3636 Brisbane Facsimile 61 2 9691 3339 2 December Final dividend payable 31 December Half year end Qantas Share Registry 60 Carrington Street 1999 Sydney NSW 1115 18 February Half year result Australia announcement Telephone 61 2 8234 5470 3 March Record date for interim Facsimile 61 2 8234 5050 dividend 31 March Interim dividend payable Depositary for American 30 June Year end Depositary Receipts 19 August Preliminary final result The Bank of New York announcement ADR Division 3 November Record date for final 101 Barclay Street dividend New York NY USA 17 November Annual General Meeting Telephone 1 212 815 2218 Adelaide Facsimile 1 212 571 3050 1 December Final dividend payable General Counsel & Company Secretary Brett Johnson Internet Address http://www.qantas.com.au All amounts are expressed in Australian dollars unless otherwise stated. Brought to you by Global Reports Operating profit before abnormals and tax of $478 -

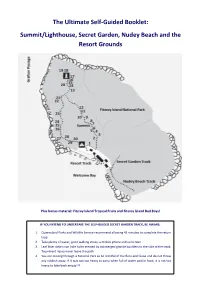

The Ultimate Self-Guided Booklet: Summit/Lighthouse, Secret Garden, Nudey Beach and the Resort Grounds

The Ultimate Self-Guided Booklet: Summit/Lighthouse, Secret Garden, Nudey Beach and the Resort Grounds Plus bonus material: Fitzroy Island Tropical Fruits and Fitzroy Island Bad Boys! IF YOU INTEND TO UNDERTAKE THE SELF-GUIDED SECRET GARDEN TRACK, BE AWARE: 1. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service recommend allowing 45 minutes to complete the return loop 2. Take plenty of water, good walking shoes, a mobile phone and sunscreen 3. Leaf litter debris can hide holes created by submerged granite boulders to the side of the track. To prevent injury never leave the path 4. You are moving through a National Park so be mindful of the flora and fauna and do not throw any rubbish away. If it was not too heavy to carry when full of water and/or food, it is not too heavy to take back empty!!! The information in this booklet is dedicated to all those that have called Fitzroy Island home, from the island’s original inhabitants, the Gunggandji people, to the military and lightkeepers who each played their role in shaping the island’s fate. The Gunggandji were walking these paths before paths existed, living off these trees and surviving in this forest for thousands of years before the first European explorers ever set foot on this land. When war threatened our shores the men of the No. 28 Radar Station stepped up to protect these lands; their influence can still be seen across the island today as can the Lightkeepers that came after them. Each served their country in isolation in lieu of modern comforts. -

Reef Trust Offsets Plan and Calculator

Reef Trust Offsets Plan and Calculator October 2017 SUMMARY 1. Background ‘Biodiversity offsetting’ is a mechanism whereby the permitted environmental impacts of development projects are compensated through conservation activities that yield a gain at least equivalent to the impact. This project is an extension of a project that was funded by the National Environmental Science Programme’s (NESP) Tropical Water Quality Hub (“Phase 1”). The purpose of the Phase 1 project was to design a scientifically robust calculation approach to determine the amount of money that a proponent would pay when voluntarily using the Reef Trust as an offset provider (Maron et al. 2016). The current project was funded by the Department of the Environment and Energy (Department) to address the gaps in the prototype calculator and develop a Reef Trust Offsets Plan. Background and methods are detailed in Appendix 1. 2. Purpose The purpose of the Reef Trust Offsets Plan (Plan) is to provide guidance on determination of offset costs, actions, and locations for Great Barrier Reef (Reef) biodiversity offsets delivered through the Reef Trust on behalf of approval holders under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). 3. Structure The Reef Trust Offsets Plan and Calculator includes this summary document and five appendices, and the calculation spreadsheet: Appendix 1. Background and Methods Appendix 2. Offset Approach for Surrogates Appendix 3. Summary of Literature Review and Expert Elicitation Appendix 4. Case Studies Appendix 5. References Reef Trust Calculator (xls) 4. Context Offsets will be implemented by the Reef Trust only 1) after impacts have been avoided and mitigated according to the mitigation hierarchy, 2) in accordance with the EPBC Act Environmental Offsets Policy and other relevant policies and guidelines, and 3) through voluntary arrangements with proponents (Figure 1) which then become binding conditions of approval.