Mission 66 and the Environmental Era, 1952 Through 1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dedication to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

STUDY, LEARN AND LIVE (continued) SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY JESUIT MISSION “WHAT WE DO HERE, WHICH IS ESPECIALLY UNIQUE, IS TO The Mission of Saint Louis University is the pursuit of truth for the greater PROVIDE A COMMUNITY WITHIN THE COMMUNITY FOR OUR glory of God and for the service of humanity. The University seeks excellence in UNDERREPRESENTED MINORITY STUDENTS. THE FEELING OF the fulfillment of its corporate purposes of teaching, research, healthcare and service to the community. It is dedicated to leadership in the continuing quest BELONGING ENHANCES SOCIAL, ACADEMIC AND EMOTIONAL DEDICATION TO for understanding of God’s creation and for the discovery, dissemination and DEVELOPMENT.” – MICHAEL RAILEY, M.D. integration of the values, knowledge and skills required to transform society in the spirit of the Gospels. As a Catholic, Jesuit university, this pursuit is motivated DIVERSITY, EQUITY You’ll love our city! Check out the new sports-anchored entertainment district by the inspiration and values of the Judeo-Christian tradition and is guided by in the heart of downtown Ballpark Village St. Louis! Attend one of the over 150 the spiritual and intellectual ideals of the Society of Jesus. events scheduled each year including concerts, family shows, community events AND INCLUSION and Saint Louis University men’s and women’s Billiken basketball games at the on Saint Louis University celebrating over 200 years in Jesuit education. campus 10,600 seat Chaifetz Arena. Check out the trendiest boutiques and upscale dining establishments in Clayton and the Central West End. If live music is your OFFICE OF DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION thing, Soulard boasts some of the best blues venues in town. -

1 a Premier Class a Office Building in Downtown St. Louis with Rich Amenities and Spectacular Views

800 MARKET STREET | ST. LOUIS, MO 63101 A premier Class A office building in Downtown St. Louis with rich amenities and spectacular views Jones Lang LaSalle Americas, Inc., a licensed real estate broker 1 BUILDING HIGHLIGHTS Bank of America Plaza provides a premium tenant experience with spectacular views of the city. The building's common areas bring people together with convenient and comfortable lobbies and lounges. The tech-equipped conference center provides meeting space for up to 250 people. While boasting amazing views of Citygarden, the fully-staffed fitness center focuses on employee well-being with top-of-the-line equipment, personal training and group classes. » 30-story designated BOMA 360 Performance Building » Beautiful multi-million dollar renovations of atrium, café, common areas and amenities » On-site amenities + Fitness center + Conference center + Retail banking + 24-hour security + Sundry shop + Café (serves breakfast and lunch) » Attached and covered 2,100-car parking garage with reserved spots available » On-site property management » On-site building engineering staff » Unobstructed views of Citygarden, Busch Stadium, Kiener Plaza and the Gateway Arch » Excellent highway access » Lease rates from $20.00 - $22.00 per SF 2 MORE THAN 32,000 SF OF COMMON AREAS AND TENANT AMENITIES fitness center | conference center | on-site café | sundry shop | large tenant lounge 3 LARGE BLOCK OF CONTIGUOUS SPACE 30 29 Bank of America Plaza currently offers up to 72,876 sf of contiguous 28 space across 3 full floors and 1 partial floor. These upper tier floors offer 27 excellent views of downtown St. Louis from every angle - Citygarden, 26 Busch Stadium, the Gateway Arch and Union Station. -

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Bus and Motorcoach Drop-Off for Gateway Arch Bus Drop-Off Is Located on Southbound Memorial Drive Behind What Was Previously the Millennium Hotel

Effective Summer 2016 Bus and Motorcoach Drop-Off for Gateway Arch Bus drop-off is located on Southbound Memorial Drive behind what was previously the Millennium Hotel. Allows for accessible path for those visiting the Gateway Arch. Bus drop-off available for a MAXIMUM of 15 minutes. No parking is allowed in this space. Located South of the Gateway Arch on Leonor K. Sullivan Blvd. between Poplar Street Bridge and Chouteau Ave. From Illinois: Poplar Street Bridge Heading WEST on the Poplar Street Bridge, continue on Interstate 64 West. Take exit 40A toward Stadium/Tucker Blvd. Continue straight off the exit (slightly LEFT) onto S. 9th Street. Continue one block north then take the next RIGHT turn on Walnut Street. Continue EAST on Walnut Street then turn RIGHT on Memorial Drive. Bus drop-off inlet will be on the right immediately after turning onto southbound Memorial Drive. From Illinois: MLK Bridge Heading WEST on the Martin Luther King Bridge, make a SLIGHT RIGHT to stay on N 3rd Street. Turn LEFT on Carr Street. Turn LEFT on Broadway. Continue South on Broadway then turn LEFT on Walnut St. Turn RIGHT on Memorial Drive. Bus drop-off inlet will be on the right immediately after turning onto southbound Memorial Drive. From Illinois: Eads Bridge Heading WEST on Eads Bridge, continue straight onto Washington Avenue. Turn left on Broadway. Continue South on Broadway then turn LEFT on Walnut St. Turn RIGHT on Memorial Drive. Bus drop-off inlet will be on the right immediately after turning onto southbound Memorial Drive. From Illinois: Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge Heading WEST on the Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge, take the LEFT exit for N. -

Overview History of the National Park Service, 2019

Description of document: Overview History of the National Park Service, 2019 Requested date: 04-June-2020 Release date: 24-June-2020 Posted date: 13-July-2020 Source of document: NPS FOIA Officer 12795 W. Alameda Parkway P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 Fax: Call for options - 1-855-NPS-FOIA Email: [email protected] FOIA.gov The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. From: FOIA, NPS <[email protected]> Sent: Wed, Jun 24, 2020 8:30 am Subject: 20-927 NPS history presentation FOIA Response Your request is granted in full. -

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition

Beautiful Dreams, Breathtaking Visions: Drawings from the 1947-1948 Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Architectural Competition BY JENNIFER CLARK The seven-person jury seated around a table in the Old Courthouse with competition advisor George Howe in 1947. The jury met twice to assess designs and decide what the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial would look like. The designs included far more than a memorial structure. A landscaped 90-acre park, various structures, water features, a campfire theater, museum buildings, and restaurants were also part of the designs. (Image: National Park Service, Gateway Arch National Park) 8 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2018 Today it is hard to conceive of any monument Saint Louis Art Museum; Roland A. Wank, the chief that could represent so perfectly St. Louis’ role architect of the Tennessee Valley Authority; William in westward expansion as the Gateway Arch. The W. Wurster, dean of architecture at MIT; and Richard city’s skyline is so defined by the Arch that it J. Neutra, a well-known modernist architect. George seems impossible that any other monument could Howe was present for the jury’s deliberations and stand there. However, when the Jefferson National made comments, but he had no vote. Expansion Memorial (JNEM) was created by LaBeaume created a detailed booklet for the executive order in 1935, no one knew what form competition to illustrate the many driving forces the memorial would take. In 1947, an architectural behind the memorial and the different needs it was competition was held, financed by the Jefferson intended to fulfill. Concerns included adequate National Expansion Memorial Association, parking, the ability of the National Park Service a nonprofit agency responsible for the early to preserve the area as a historic site, and the development of the memorial idea. -

Thank You, George & Melissa Paz Caring for Your Museum

GATEWAY ARCH PARK FOUNDATION CONNECTION www.archpark.org @GatewayArchPark TERF ¯ BLUES AT THE ARCH E SUNRISE YOGA IN S Looking Join us online every As we all look forward T Tuesday at 7 a.m. The fih annual to Blues at the Arch W at the Gateway Arch Winterfest will return 2021, you can still Ahead 11 Park Foundation to Kiener Plaza in 2020 WINTERFESTrelive the great GATEWAY ARCH PARK FOUNDATION Gateway Arch Facebook page. featuring a whimsical moments G of this N Our “Salute to Veterans” tribute is presented by walk-through holiday A O Park Foundation T I Sco Credit Union. For more information, visit the light display. Stay tuned year’s E T W A A D signature events Gateway Arch Park Foundation Facebook page to www.archpark.org event on Y N A U R F O continue. and website. for more information. our website. C H P A R K Caring for Your Museum The Museum at the Gateway Arch receives an update. ICE RINK MARKET IGLOO VILLAGE The Gateway Arch Westward Expansion period of the United States with National Park is a more perspectives from the cultures involved. Visitors can learn how events that took place in downtown St. Louis the 90+ acres of Gateway Arch National Park shaped oasis. Amid the American history. beautifully forested The new Museum was designed to be a hands-on surroundings found experience with many tactile exhibits and, as anticipated, within one of the it requires regular maintenance and repairs. Gateway Arch Park Foundation serves our National few urban national Park in many ways, including funding ongoing exhibit parks west of the maintenance. -

Currents and Undercurrents: an Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 476 001 SO 034 781 AUTHOR McKay, Kathryn L.; Renk, Nancy F. TITLE Currents and Undercurrents: An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-01-00 NOTE 589p. AVAILABLE FROM Lake Roosevelt Recreation Area, 1008 Crest Drive, Coulee Dam, WA 99116. Tel: 509-633-9441; Fax: 509-633-9332; Web site: http://www.nps.gov/ laro/adhi/adhi.htm. PUB TYPE Books (010) Historical Materials (060) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS --- *Government Role; Higher Education; *Land Use; *Parks; Physical Geography; *Recreational Facilities; Rivers; Social Studies; United States History IDENTIFIERS Cultural Resources; Management Practices; National Park Service; Reservoirs ABSTRACT The 1,259-mile Columbia River flows out of Canada andacross eastern Washington state, forming the border between Washington andOregon. In 1941 the federal government dammed the Columbia River at the north endof Grand Coulee, creating a man-made reservoir named Lake Roosevelt that inundated homes, farms, and businesses, and disrupted the lives ofmany. Although Congress never enacted specific authorization to createa park, it passed generic legislation that gave the Park Service authorityat the National Recreation Area (NRA). Lake Roosevelt's shoreline totalsmore than 500 miles of cliffs and gentle slopes. The Lake Roosevelt NationalRecreation Area (LARO) was officially created in 1946. This historical study documents -

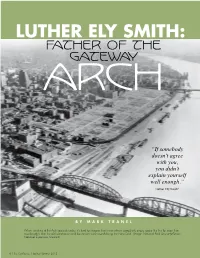

Father of the Gateway Arch | the Confluence

LUTHER ELY SMITH: Father of the Gateway Arch “If somebody doesn’t agree with you, you didn’t explain yourself well enough.” Luther Ely Smith1 BY MARK TRANEL When standing at the Arch grounds today, it’s hard to imagine that it was almost completely empty space like this for more than two decades after the old warehouses and businesses were razed during the New Deal. (Image: National Park Service-Jefferson National Expansion Museum) 6 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2012 As St. Louis pursues an initiative established a Civil Service to frame the Gateway Arch with more Commission in 1941, he was active and esthetic grounds, and with appointed to leadership roles, first as a goal of completing the project by vice-chairman until 1945 and then 2015, the legacy of Luther Ely Smith as chairman until 1950. From 1939 and his unique role in the creation to 1941, Smith was chairman of of the Jefferson National Expansion the organization committee for the Memorial (the national park Missouri non-partisan court plan, surrounding the Arch) is a reminder of which successfully led an initiative the tenacity such major civic projects petition to amend the Missouri require. What is today a national park Constitution to appoint appellate was in the mid-nineteenth century the court judges by merit rather than heart of commerce on the Missouri Trained as a lawyer, Luther Ely Smith political connections.3 He was also and Mississippi rivers; forty years (1873-1951) was at the forefront of urban president of the St. Louis City Club.4 later it was the first dilapidated urban planning. -

Our Facilities Meetings and Events Our Rooms Eat and Drink out and About

T: +1 314 421 1776 E: [email protected] OUR ROOMS EAT AND DRINK GUEST ROOMS LOBBY BAR Our standard guest rooms are a field of sweet dreams thanks to the Hilton Serenity Bed Meet your friends or just people watch in Collection™. All rooms also feature high speed internet access and spectacular views of the Lobby Bar and savor a cocktail, beer or the city, Busch Stadium, and the Gateway Arch. glass of wine along with a selection of sandwiches, salads or soups. ACCESSIBLE ROOMS Appointed like our standard guest rooms, our accessible rooms also feature options such MARKET STREET BISTRO AND BAR as roll-in shower or low tub with grab bars and wide doorways. Enjoy American-style breakfast, lunch or dinner prepared with fresh seasonal EXECUTIVE LEVEL Guests staying in our fully appointed Executive Level rooms enjoy breakfast and evening ingredients and accented with views of appetizers in our Evecutive Level Lounge. downtown St. Louis. THREE SIXTY ROOFTOP BAR SUITES With separate living and sleeping areas, our suites are perfect for families or guests Perched on the 26th Floor, our rooftop bar preferring more space or for hospitality suites. Watch the game at Busch Stadium from with seating indoors and out oers soaring the two-bedroom Presidential Suite. views of the St. Louis skyline, the Gateway Arch and an easy base inside Busch Stadium. OUR FACILITIES HILTON FITNESS BY PRECOR © Full equipped with the latest generation cardio and strength training machines, Hilton Fitness by Precor© takes a personalized approach that provides the idea balance to demanding daily lives. -

STLRS Fact Sheet

HYATT REGENCY ST. LOUIS AT THE ARCH 315 Chestnut Street St. Louis, Missouri 63102, USA T +1 314 655 1234 F +1 314 241 9839 stlouisarch.regency.hyatt.com ACCOMMODATIONS RESTAURANTS & BARS 910 guestrooms, including 62 suites / parlors, 388 kings, • Red Kitchen & Bar: daily breakfast buffet, seasonal menu and and 442 double / doubles creative cocktail concoctions All Accommodations Offer • Starbucks®: full service one-stop coffee shop; conveniently located • Free Wi-Fi is available in guestrooms and social spaces like lobbies on the lobby level and restaurants, excluding meeting spaces • Brewhouse Historical Sports Bar: a huge selection of local craft beers, • Hyatt Grand Bed® in-house smoked meats and BBQ • Spectacular Gateway Arch or Downtown view rooms • Ruth’s Chris Steak House: fine dining; famous sizzling steaks, seafood • 50-inch flat-screen television with remote control, in-room pay movies and signature cocktails • Video checkout RECREATIONAL FACILITIES • Telephone with voicemail and data port • StayFit™ Center featuring the latest equipment such as Life Fitness® cardio • Deluxe bath amenities and hair dryer and strength-training machines complete with flat-screen televisions • Coffeemaker • In-room refrigerator MEETING & EVENT SPACE • Iron / ironing board • A total of 83,000 square feet of indoor / outdoor stacked meeting • iHome® alarm clock radio and event space • Dog friendly • Grand Ballroom offers 19,758 square feet of space with 14,600 square feet of prefunction space SERVICES & FACILITIES • Regency Ballroom offers 16,800 -

Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2001 Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion Bradley David Roeder University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Roeder, Bradley David, "Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion" (2001). Theses (Historic Preservation). 322. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Roeder, Bradley David (2002). Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Roeder, Bradley David (2002). Creation and Destruction: Mitchell/Giurgola's Liberty Bell Pavilion. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/322 uNivERsmy PENNSYLVANIA. UBKARIES CREATION AND DESTRUCTION: MITCHELL/GIURGOLA'S LIBERTY BELL PAVILION Bradley David Roeder A THESIS In Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2002 Advisor Reader David G. DeLong Samuel Y. Harris Professor of Architecture Adjunct Professor of Architecture I^UOAjA/t? Graduate Group Chair i Erank G.