Screen1.Ps (Mpage)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Designer Player

The Designer Player Rodrigo Villagomez Baseball is a multi-billion dollar entertainment industry. The modern age of American sports has seen to it that we no longer look at baseball as just "America's pastime." We must now see it as another corporation striving to produce a product that will be consumed by the populous. It is a corporation that produces the reluctant hero, a man who begrudgingly accepts the title "role model." These players are under intense pressure to continually be on top of their game. They are driven by relentless fans to achieve greater levels of strength and prowess. Consequentially, because of this pressure more professional baseball players are turning to performance-enhancing drugs, more specifically steroids, to aid them in their quest for greatness. Many believe that these drugs decrease the integrity of the players and ultimately the game itself. My opinion is that if it were not for the small percentage of players who have recently been found to use steroids, baseball would not be enjoying the success it does today. So really baseball should be thanking these players for actually keeping the game popular. Before this argument begins, let's first look at the clinical definition of a steroid. A steroid is "any group of organic compounds belonging to the general class of biochemicals called lipids, which are easily soluble in organic solvents and slightly soluble in water" (Dempsey). Now let's put it in terms that you and I can understand with the help of author Dayn Perry. "Testosterone has an androgenic, or masculizing, function and an anabolic, or tissue-building, function. -

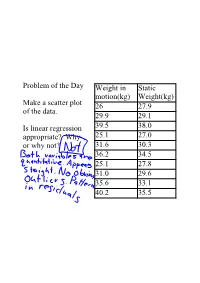

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds Gavel.) Good Afternoon and Welcome to the National Press Club. My Name Is Donna Leinwand. I'm a Repor

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH JEFF IDELSON SUBJECT: JEFF IDELSON, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME, IS SCHEDULED TO SPEAK AT A NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON MAY 11. HALL OF FAME THIRD BASEMAN BROOKS ROBINSON WILL BE A SPECIAL GUEST. MODERATOR: DONNA LEINWAND, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MAY 11, 2009 (C) COPYRIGHT 2009, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Donna Leinwand. I’m a reporter at USA Today and I’m president of the National Press Club. We’re the world’s leading professional organization for journalists and are committed to a future of journalism by providing informative programming, journalism education and fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. On behalf of our 3,500 members worldwide, I’d like to welcome our speaker and our guests in the audience today. I’d also like to welcome those of you who are watching us on C-Span. We’re looking forward to today’s speech, and afterwards, I’ll ask as many questions from the audience as time permits. -

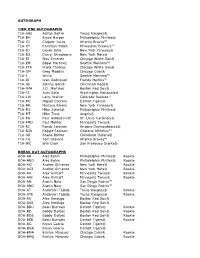

2021 Topps Tier One Checklist .Xls

AUTOGRAPH TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS T1A-ABE Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® T1A-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ T1A-CY Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ T1A-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® T1A-DS Darryl Strawberry New York Mets® T1A-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® T1A-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ T1A-FTA Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® T1A-GM Greg Maddux Chicago Cubs® T1A-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ T1A-IR Ivan Rodriguez Florida Marlins™ T1A-JB Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® T1A-JMA J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® T1A-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® T1A-LW Larry Walker Colorado Rockies™ T1A-MC Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® T1A-MR Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® T1A-MS Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-MT Mike Trout Angels® T1A-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® T1A-PMO Paul Molitor Minnesota Twins® T1A-RJ Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® T1A-RJA Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ T1A-SB Shane Bieber Cleveland Indians® T1A-TG Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ T1A-WC Will Clark San Francisco Giants® BREAK OUT AUTOGRAPHS BOA-AB Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-AG Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AGI Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AK Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AKI Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AN Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-ANO Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-AT Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-ATE Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-AV Alex Verdugo Boston -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

July 10-14, 2015 SQ

OVER 400,000 July 10-14, 2015 SQ. FEET OF FUN Duke Energy Convention Center • Cincinnati, OH LEGENDS PROGRAMTM The Legends Program gives fans the opportunity to meet some Major League Baseball® is looking for volunteers to assist of the past and present Major League Baseball® legends. With with the events surrounding the 2015 MLB® All-Star Week™. four great ways to meet players, the Legends Program provides Volunteer opportunities during MLB® All-Star Week™ include a once in a life time experience for all fans. Fans can get free T-Mobile All-Star FanFest,® MLB® community events and autographs, participate in clinics coached by the legends, take MLB® All-Star hospitality events. The events will take place a photo at the World’s Largest Baseball, or sit in and listen to July 10th through July 14th. Volunteers must be 18 years or the great baseball stories in our Question and Answer sessions. older and can register now on ALLSTARGAME.COM to be All opportunities are included in the price of admission. part of all the fun and excitement. Don’t miss out on this unique and fun opportunity. Question and Answer Sessions Photo Opportunities Ozzie Smith (HOF) Paul Molitor (HOF) Diamond Clinics Autograph Sessions Dave Winfield (HOF) Alex Gordon Past legends who have made appearances include: • Lou Brock (HOF) • Bryce Harper • Rollie Fingers (HOF) • Clayton Kershaw • Barry Larkin (HOF) • Andrew McCutchen • Miguel Cabrera • Giancarlo Stanton Mr. Red Legs Visit for an updated schedule FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT of appearances and autograph sessions *All appearances are subject to change* Duke Energy Convention Center July 10-14, 2015 LIVE OUT YOUR ® BASEBALL DREAMS This July you can experience Major League Baseball® in ways you’ve only dreamed about. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

BASE BOWMAN ICONS PROSPECTS 1 Wander Franco

BASE BOWMAN ICONS PROSPECTS 1 Wander Franco Tampa Bay Rays™ 4 Cristian Pache Atlanta Braves™ 5 Matt Manning Detroit Tigers® 7 Casey Mize Detroit Tigers® 9 Dylan Carlson St. Louis Cardinals® 10 Sixto Sanchez Miami Marlins® 11 JJ Bleday Miami Marlins® 13 Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® 14 Jasson Dominguez New York Yankees® 17 Nick Madrigal Chicago White Sox® 18 Royce Lewis Minnesota Twins® 19 Jo Adell Angels® 22 MacKenzie Gore San Diego Padres™ 26 Julio Rodriguez Seattle Mariners™ 27 Adley Rutschman Baltimore Orioles® 28 Nate Pearson Toronto Blue Jays® 30 CJ Abrams San Diego Padres™ 32 Nolan Gorman St. Louis Cardinals® 34 Jarred Kelenic Seattle Mariners™ 37 Forrest Whitley Houston Astros® 38 Marco Luciano San Francisco Giants® 39 Bobby Witt Jr. Kansas City Royals® 44 Andrew Vaughn Chicago White Sox® 46 Joey Bart San Francisco Giants® 50 Riley Greene Detroit Tigers® BOWMAN ICONS ROOKIES 2 Luis Robert Chicago White Sox® Rookie 3 Justin Dunn Seattle Mariners™ Rookie 6 Bobby Bradley Cleveland Indians® Rookie 8 Yoshi Tsutsugo Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 12 Aaron Civale Cleveland Indians® Rookie 15 Trent Grisham San Diego Padres™ Rookie 16 Dustin May Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 20 A.J. Puk Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 21 Nico Hoerner Chicago Cubs® Rookie 23 Sean Murphy Oakland Athletics™ Rookie 24 Yordan Alvarez Houston Astros® Rookie 25 Jordan Yamamoto Miami Marlins® Rookie 29 Michel Baez San Diego Padres™ Rookie 31 Shun Yamaguchi Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 33 Anthony Kay Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 35 Brusdar Graterol Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 36 Bo -

Golfing Sponsorship Opportunities

201 9 MONDAY, JULY 29, 2019 PERSIMMON WOODS GOLF CLUB Sponsorship Opportunities TITLE SPONSOR • $50,000 AUCTION SPONSOR • $1,500 PRESENTING SPONSORS • $25,000 BREAKFAST & SHOPPING EXPERIENCE SPONSOR • $2,500 DOUBLE PLAY SPONSORS • $10,000 EXTRA INNINGS RECEPTION SPONSOR • $2,500 FOURSOME SPONSORS • $4,000 TEE SIGN SPONSOR • $250 INDIVIDUAL GOLFER • $1,200 (one available) Non-Golfing Sponsorship Opportunities AUCTION SPONSOR (one available) • $1,500 Company name and/or logo featured on auction mobile bidding platform • Company branded signage in auction area • One (1) full color, company-branded tee sign on course • Admission for two (2) to Extra Innings Awards Reception immediately following play of golf BREAKFAST & SHOPPING EXPERIENCE SPONSOR (one available) • $2,500 Company Branded Signage in Breakfast Area • Company Branded Signage in Gi Bag Shopping Area • One (1) Full Color, Company Branded Tee Sign On Course • Opportunity to place product or company information in golfer gi bags • Admission for two (2) to Extra Innings Awards Reception immediately following Golf • One (1) Autographed Item signed by host EXTRA INNINGS RECEPTION SPONSOR (one available) • $2,500 Company branded signage at Extra Innings Awards Reception • One (1) full color, company-branded tee sign on course • Opportunity to place product or company information in golfer gi bags • Admissions for two (2) to Extra Innings Awards Reception immediately following play of golf • One (1) Autographed Item signed by host The Pujols Family Foundation Celebrity Golf Classic serves as a fundraising event to support the work of the foundation. By participating in the golf classic, you help to provide the necessary resources to support programs benefiing the Down syndrome community in St. -

Castrovince | October 23Rd, 2016 CLEVELAND -- the Baseball Season Ends with Someone Else Celebrating

C's the day before: Chicago, Cleveland ready By Anthony Castrovince / MLB.com | @castrovince | October 23rd, 2016 CLEVELAND -- The baseball season ends with someone else celebrating. That's just how it is for fans of the Indians and Cubs. And then winter begins, and, to paraphrase the great meteorologist Phil Connors from "Groundhog Day," it is cold, it is gray and it lasts the rest of your life. The city of Cleveland has had 68 of those salt-spreading, ice-chopping, snow-shoveling winters between Tribe titles, while Chicagoans with an affinity for the North Siders have all been biding their time in the wintry winds since, in all probability, well before birth. Remarkably, it's been 108 years since the Cubs were last on top of the baseball world. So if patience is a virtue, the Cubs and Tribe are as virtuous as they come. And the 2016 World Series that arrives with Monday's Media Day - - the pinch-us, we're-really-here appetizer to Tuesday's intensely anticipated Game 1 at Progressive Field -- is one pitting fan bases of shared circumstances and sentiments against each other. These are two cities, separated by just 350 miles, on the Great Lakes with no great shakes in the realm of baseball background, and that has instilled in their people a common and eventually unmet refrain of "Why not us?" But for one of them, the tide will soon turn and so, too, will the response: "Really? Us?" Yes, you. Imagine what that would feel like for Norman Rosen. He's 90 years old and wise to the patience required of Cubs fandom. -

JOE MAUER DAY •Q"Esgs0 G•Ltair-Ci`

STATE of MINNESOTA WHEREAS: Joseph Patrick Mauer was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota on April 19, 1983; and WHEREAS: Upon graduating from high school, Joe was selected by the Minnesota Twins as the number one overall pick in the first round of the 2001 Major League Baseball First-Year Player Draft; and WHEREAS: On April 5, 2004, Joe made his Major League debut at the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, going 2-for-3 with two walks in the Twins' 7-4 victory over the Cleveland Indians; and WHEREAS: He became the first catcher to ever win the American League batting title, won three AL batting crowns overall, was a six-time AL All-Star, earned five Louisville Slugger "Silver Slugger Awards" and three Rawlings Gold Glove Awards, and was the 2009 AL Most Valuable Player; and WHEREAS: Joe spent his entire 15-year Major League career with the Minnesota Twins, and on September 30, 2018, he played his final game, retiring with a career .306 batting average, 2,123 hits, 428 doubles, 30 triples, 143 home runs, 923 RBI, 1,018 runs scored, and 939 walks; and WHEREAS: Joe ranks first in Minnesota Twins history for doubles, times on base, and games played as catcher; second in games played, hits, and walks; third in batting average, runs and total bases; fifth in RBI; and eleventh in home runs; and WHEREAS: Joe and his wife, Maddie, are active community leaders, annually hosting fundraisers and volunteering countless hours to various charities throughout Twins Territory; and WHEREAS: In 2019, Joe will become the eighth Minnesota Twin to have his number retired by the organization, joining Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Tony Oliva, Kent Hrbek, Kirby Puckett, Bert Blyleven, and Tom Kelly.