Preventing Head Trauma from Football Field to Shop Floor to Battlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1983 Topps Football Card Checklist

1983 TOPPS FOOTBALL CARD CHECKLIST 1 Ken Anderson (Record Breaker) 2 Tony Dorsett (Record Breaker) 3 Dan Fouts (Record Breaker) 4 Joe Montana (Record Breaker) 5 Mark Moseley (Record Breaker) 6 Mike Nelms (Record Breaker) 7 Darrol Ray 8 John Riggins (Record Breaker) 9 Fulton Walker 10 NFC Championship 11 AFC Championship 12 Super Bowl XVII 13 Falcons Team Leaders (William Andrews) 14 William Andrews 15 Steve Bartkowski 16 Bobby Butler 17 Buddy Curry 18 Alfred Jackson 19 Alfred Jenkins 20 Kenny Johnson 21 Mike Kenn 22 Mick Luckhurst 23 Junior Miller 24 Al Richardson 25 Gerald Riggs 26 R.C. Thielemann 27 Jeff Van Note 28 Bears Team Leaders (Walter Payton) 29 Brian Baschnagel 30 Dan Hampton 31 Mike Hartenstine 32 Noah Jackson 33 Jim McMahon 34 Emery Moorehead 35 Bob Parsons 36 Walter Payton 37 Terry Schmidt 38 Mike Singletary 39 Matt Suhey 40 Rickey Watts 41 Otis Wilson 42 Cowboys Team Leaders (Tony Dorsett) Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Bob Breunig 44 Doug Cosbie 45 Pat Donovan 46 Tony Dorsett 47 Tony Hill 48 Butch Johnson 49 Ed "Too Tall" Jones 50 Harvey Martin 51 Drew Pearson 52 Rafael Septien 53 Ron Springs 54 Dennis Thurman 55 Everson Walls 56 Danny White 57 Randy White 58 Lions Team Leaders (Billy Sims) 59 Al Baker 60 Dexter Bussey 61 Gary Danielson 62 Keith Dorney 63 Doug English 64 Ken Fantetti 65 Alvin Hall 66 David Hill 67 Eric Hipple 68 Ed Murray 69 Freddie Scott 70 Billy Sims 71 Tom Skladany 72 Leonard Thompson 73 Bobby Watkins 74 Packers Team Leaders (Eddie Lee Ivery) 75 John Anderson 76 Paul Coffman 77 Lynn -

NFL's Goodell Doesn't Agree with Kaepernick's Actions

Sports FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2016 43 T Romo heads list of declining NFL players DALLAS: Tony Romo followed the best season of his career in 2014 with one injury after another. The question no longer is whether Romo can duplicate the success he had just two years ago when he led the Dallas Cowboys to 12 wins and the NFC East title. Rather, people wonder if can stay healthy to play at all. Romo missed 12 games in 2015 after he broke his left collarbone twice. He begins this year on the sideline after suffering a back injury in the presea- son. The four-time Pro Bowl quarterback is clearly on the decline. Here are other players who could trend downward in 2016: Jason Peters, LT, Eagles: He’s an eight-time Pro Bowl pick and two-time All-Pro who has missed only two games in the past three seasons. But the 34-year-old Peters isn’t the dominant blocker he used to be. He has 18 penalties and 12 sacks allowed over the last two seasons. Chris Johnson, RB, Cardinals: Johnson was on his way to his sev- enth 1,000-yard season in eight years before getting hurt last sea- son. He ran for 814 yards in 11 games. His injury gave David Johnson an opportunity to play more and he was dynamic. The Cardinals are in good hands with either Johnson, but expect David to get the ball more than Chris. Demaryius Thomas, WR, Broncos: Thomas had 105 catches for 1,304 yards and six TDs in 2015 despite Peyton Manning’s rapid decline. -

1984 Topps Football Card Checklist

1984 Topps Football Card Checklist 1 Eric Dickerson 2 Ali Haji-Sheikh 3 Franco Harris 4 Mark Moseley 5 John Riggins 6 Jan Stenerud 7 AFC Championship 8 NFC Championship 9 Super Bowl XVIII (Marcus Allen) 10 Colts Team Leaders (Curtis Dickey) 11 Raul Allegre 12 Curtis Dickey 13 Ray Donaldson 14 Nesby Glasgow 15 Chris Hinton 16 Vernon Maxwell 17 Randy McMillan 18 Mike Pagel 19 Rohn Stark 20 Leo Wisniewski 21 Bills Team Leaders (Joe Cribbs) 22 Jerry Butler 23 Joe Danelo 24 Joe Ferguson 25 Steve Freeman 26 Roosevelt Leaks 27 Frank Lewis 28 Eugene Marve 29 Booker Moore 30 Fred Smerlas 31 Ben Williams 32 Bengals Team Ldrs. (Cris Collinsworth) 33 Charles Alexander 34 Ken Anderson 35 Ken Anderson 36 Jim Breech 37 Cris Collinsworth 38 Cris Collinsworth 39 Isaac Curtis 40 Eddie Edwards 41 Ray Horton 42 Pete Johnson Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Steve Kreider 44 Max Montoya 45 Anthony Munoz 46 Reggie Williams 47 Browns Team Leaders (Mike Pruitt) 48 Matt Bahr 49 Chip Banks 50 Tom Cousineau 51 Joe DeLamielleure 52 Doug Dieken 53 Bob Golic 54 Bobby Jones 55 Dave Logan 56 Clay Matthews 57 Paul McDonald 58 Ozzie Newsome 59 Ozzie Newsome 60 Mike Pruitt 61 Broncos Team Ldrs. (Steve Watson) 62 Barney Chavous 63 John Elway 64 Steve Foley 65 Tom Jackson 66 Rick Karlis 67 Luke Prestridge 68 Zack Thomas 69 Rick Upchurch 70 Steve Watson 71 Sammy Winder 72 Louis Wright 73 Oilers Team Leaders (Tim Smith) 74 Jesse Baker 75 Gregg Bingham 76 Robert Brazile 77 Steve Brown 78 Chris Dressel 79 Doug France 80 Florian Kempf 81 Carl Roaches 82 Tim Smith 83 Willie Tullis 84 Chiefs Team Leaders (Carlos Carson) 85 Mike Bell 86 Theotis Brown 87 Carlos Carson 88 Carlos Carson 89 Deron Cherry Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 90 Gary Green 91 Billy Jackson 92 Bill Kenney 93 Bill Kenney 94 Nick Lowery 95 Henry Marshall 96 Art Still 97 Raiders Team Ldrs. -

Utilizing Public Policy and Technology to Strengthen Organ Donor Programs

UTILIZING PUBLIC POLICY AND TECHNOLOGY TO STRENGTHEN ORGAN DONOR PROGRAMS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INFORMATION POLICY, CENSUS, AND NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 25, 2007 Serial No. 110–57 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html http://www.oversight.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 43–028 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:33 Jul 16, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\43028.TXT KATIE PsN: KATIE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HENRY A. WAXMAN, California, Chairman TOM LANTOS, California TOM DAVIS, Virginia EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOHN L. MICA, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee DIANE E. WATSON, California MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts DARRELL E. ISSA, California BRIAN HIGGINS, New York KENNY MARCHANT, Texas JOHN A. YARMUTH, Kentucky LYNN A. WESTMORELAND, Georgia BRUCE L. -

Dallas Cowboys Hard 4792.Pdf

Dallas Cowboys - Free Printable Wordsearch TOUJFRODSMITHDALEHE LLESTRAEHTBWJ MICHAELGALLUPZVTCDH NZMATMCBRIARA TDPQSNMITERRELLOWENS SBPGVZPHNWNY XYOIMSTGLYOTYDENNIS THURMANJAJFQN DBRNBDARRENWOODSONPMLHL ZVNTRILZO YAOOMQPVEHERBERTSCOTT DMAGYEVEODV WMVBNEMUNJIYHZVXSGPKK WWCRIREPGAA VJMELERDZARSDTGGETAB LVOKFIEYTRKC XDIOMICEORALVINHARP ERKSMHQNMXEPE KDUYBALRDLARRYALLENC VCKAWRCAFGRK KUOABHNLAIOWKPWHVOBBKX YRAOERREEM CUUDNYTDYWTGOTEXSCHRAM MTIFNTULSI TGZTLEPREJFHTOMRAFF ERTYIYXEISLCI UOWUQPTCARGORUZUGRNQBK LNIZWNSIOC PQNAJRBHTVSRRYBLAEL COLLINSMZESTD UGTYGMAOODIBBDLQNBZAE YWSQSAHLBTK IJEJTLTHOMASHENDERS ONXVVNDNELURA NPRABOEDVRAYFIELDWRI GHTIQROZMRJC BWRCMJLEQGKSFRISNRFY ZIKHERYEAAAH IDASABABRWJYKLEQEOPP ERIKQNTCRSYA LENNWOISEORPTASDIAQA EBLHIJNOYERR LMCQCBHSORYWUENRENNPYA PVHORHLLAL YAEQOBDOCNTJNELOIRN LWJRMDUSWAGTI JRWRLRXSPKWOOEAWSOILE IWNEEOMNULE OCIWEEOIVHJIDRRFDD ECLEACNHOIDPIW EOLVBUPDGNGKTADORHUEK RUOKRTKCPFA DMLKENQVOUCEJTEACHAR BOJCWVWENMFT UUITAIMRGADEYYESNHX SDSUDXWVDWVTE PRAOSGYVJMKKQYRNCEBA IHBCUPGIOEDR RRMNLBMXLACZZEPILQLR CARHYZLTXBUS EASVEEUDLXRFHBMNNPHWWB FOBMPKYYSZ EYIAYUFBZWPYFNDLLCL SQMWCFMSAKVEJ TERRANCE WILLIAMS DARREN WOODSON TONY TOLBERT MAT MCBRIAR TRAVIS FREDERICK DENNIS THURMAN DON MEREDITH TEX SCHRAMM BILLY JOE DUPREE TERENCE NEWMAN CHUCK HOWLEY CHRIS JONES THOMAS HENDERSON DEMARCO MURRAY BRANDON CARR BYRON JONES RUSSELL MARYLAND MICHAEL IRVIN JACK DEL RIO JAY NOVACEK DALE HELLESTRAE L P LADOUCEUR DAVE MANDERS JAY RATLIFF TYRONE CRAWFORD HARVEY MARTIN DUANE THOMAS BOB BREUNIG HERSCHEL WALKER TERRELL OWENS DAK -

Patriots Travel to London to Face the Buccaneers

PATRIOTS TRAVEL TO LONDON TO FACE THE BUCCANEERS MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-2) at TAMPA BAY BUCCANEERS (0-6) WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 21 Sunday, Oct. 25, 2009 ¹ Wembley Stadium (84,000) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 - 11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conf. 11:10 - 11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room The NFL’s International Series of regular-season Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability games returns to the United Kingdom this Sunday TBA Tampa Bay Conf. Calls when Tampa Bay hosts New England. The contest THURSDAY, OCTOBER 22 will mark the third consecutive year of an NFL 1:15 - 11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room regular-season game at London’s Wembley TBA Practice Availability Stadium. On October 26, 2008 the New Orleans Saints defeated the San Diego 3:30- 4p.m. Photo Opp (Team Depature) Chargers 37-32 before a crowd of 83,226. The International Series began on October FRIDAY, OCTOBER 24 28, 2007 when the New York Giants defeated the Miami Dolphins, 13-10. 12:50 p.m. (UK) media availability with four Said Patriots Chairman and CEO Robert Kraft, “We are proud to be selected by players in the Long Room at The Brit Oval Cricket the NFL to be featured in this year’s international game. I am sure our trip to the Ground, Kennington, London. United Kingdom will prove to be an unforgettable experience for our players and 2009 PATRIOTS SCHEDULE coaches, as well as the many fans that will travel to the game. I know that the UK is home to some of our most passionate Patriots fans and we look forward to the REGULAR SEASON (4-2) experience.” Mon., Sept. -

Appears on a Players Card, It Means That You Use the K Or P Column When He Reovers a Fumble

1981 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1981 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most. Realistic use of the players frequently below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he reovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA BALTIMORE BUFFALO CHICAGO OFFENSE OFFENSE OFFENSE OFFENSE EB: Wallace Francis EB: Ray Butler EB: Jerry Butler EB: Brian Baschnagel OC Alfred Jenkins Roger Carr Frank Lewis Rickey Watts Alfred Jackson Brian DeRoo Byron Franklin TC OA Marcus Anderson OC Reggie Smith TB OB Randy Burke Ron Jessie Ken Margerum Tackle: Mike Kenn David Shula TA TB OC Lou Piccone TB OC Tackle: Keith Van Horne Warren Bryant Kevin Williams OB Tackle: Joe Devlin Ted Albrecht Eric Sanders Tackle: Jeff Hart Ken Jones Dan Jiggetts Guard: R.C. -

2007 Washington Redskins

2007 WASHINGTON REDSKINS Record: 9-7 3rd Place – NFC East (Wild Card playoff team) Playoffs: 1st Round loss to Seattle Head Coach: Joe Gibbs 2007 9-7 Sept. 9 W 16-13 OT Miami Sept. 17 W 20-12 at Philadelphia Sept. 23 L 17-24 NY Giants Oct. 7 W 34-3 Detroit Oct. 14 L 14-17 at Green Bay Oct. 21 W 21-19 Arizona Oct. 28 L 7-52 at New England Nov. 4 W 23-20 OT at NY Jets Nov. 11 L 25-33 Philadelphia Nov. 18 L 23-28 at Dallas Nov. 25 L 13-19 at Tampa Bay Dec. 2 L 16-17 Buffalo Dec. 6 W 24-16 Chicago Dec. 16 W 22-10 at NY Giants Dec. 23 W 33-21 at Minnesota Jan. 1 W 27-6 Dallas [Playoffs] Jan. 5 L 14-35 at Seattle 1 of 3 Never a Dull Moment for the Redskins in 2007 Drama, drama and more drama. So it went for the Redskins during a 2007 season that carried elements of a Hollywood script, or a riveting novel, for that matter. As the most erudite sports historians would agree, it was a unique year for any professional team. All the while, the Redskins and their fans rode an emotional roller coaster as the burgundy and gold endured one type of adversity after another. Repeated heartbreaking losses, multiple injuries to key players, embarrassing coaching blunders, and something so unimaginable and unprecedented in NFL history, the murder of safety Sean Taylor, the team’s best player and the face of the franchise for years to come, all befell the Redskins in 2007. -

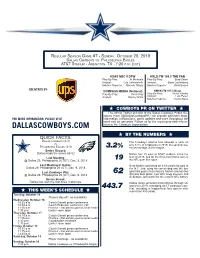

62 Dallascowboys.Com

REGULAR SEASON GAME #7 - SUNDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2019 DALLAS COWBOYS VS. PHILADELPHIA EAGLES AT&T STADIUM - ARLINGTON, TX - 7:20 P.M. (CDT) KXAS NBC 5 DFW KRLD-FM 105.3 THE FAN Play-By-Play: Al Michaels Play-By-Play: Brad Sham Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Analyst: Babe Laufenberg Sideline Reporter: Michele Tafoya Sideline Reporter: Kristi Scales DELIVERED BY: COMPASS MEDIA (National) KMVK-FM 107.5 Mega Play-By-Play: Kevin Ray Play-By-Play: Victor Villalba Analyst: Danny White Analyst: Luis Perez Sideline Reporter: Carlos Nava H COWBOYS PR ON TWITTER H The official Twitter account of the Dallas Cowboys Public Re- lations team (@DallasCowboysPR) will provide pertinent stats, FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE VISIT information, transactions, game updates and more throughout the week and on gameday. Follow us for the most up-to-date info re- DALLASCOWBOYS.COM lated to the Cowboys organization. H BY THE NUMBERS H DALLAS COWBOYS (3-3) The Cowboys offense has allowed a sack on VS. only 3.2% of dropbacks in 2019, the second-low- PHILADELPHIA EAGLES (3-3) 3.2% est percentage in the league. Series Record: Dallas leads the series 68-52 Dallas has 19 wins at AT&T stadium since the Last Meeting: start of 2016, tied for the third-most home wins in @ Dallas 29, Philadelphia 26 (OT), Dec. 9, 2018 19 the NFL over that span. Last Meeting in Dallas: Brett Maher connected on a 62-yard field goal at Dallas 29, Philadelphia 26 (OT), Dec. 9, 2018 the N.Y. Jets, tying his career-long and the lon- Last Cowboys Win: 62 gest field goal in team history. -

Shawn Springs

DECEMBER 2020 Volume 36 Issue 12 DIGEST FORMER NFL STAR’S COMPANY DEVELOPS PADDING TECHNOLOGY TO HELP SAVE LIVES Bored? Get Out the Board SORRY! IS PART OF GAMES’ REVIVAL DURING PANDEMIC Shawn IP’s Future Under Biden Springs VIEWPOINTS ON IMPACT OF THE PRESIDENT-ELECT $5.95 FULTON, MO MO FULTON, FULTON, PERMIT 38 38 PERMIT PERMIT US POSTAGE PAID PAID POSTAGE POSTAGE US US PRSRT STANDARD STANDARD PRSRT PRSRT EDITOR’S NOTE Inventors DIGEST EDITOR-IN-CHIEF REID CREAGER A Christmas Story ART DIRECTOR CARRIE BOYD Too Sweet for Words CONTRIBUTORS “MOM! Come on. No way!” STEVE BRACHMANN “Way, Reid. Very way.” ELIZABETH BREEDLOVE “So we sit down to play Scrabble for the first time in forever, and on LOUIS CARBONNEAU the first play of the game you use all your tiles with a seven-letter word DON DEBELAK for 86 points? And the word is … fathead?” ALYSON DUTCH “How ’bout that? Isn’t this a great game?” MARIE LADINO JACK LANDER “It is. In fact, I wrote about it recently.” JEREMY LOSAW “I wonder who invented Scrabble?” EILEEN MCDERMOTT “Alfred Mosher Butts. He was an unemployed architect who invented EDIE TOLCHIN the game during the Depression.” “I’ll bet the inventor played the game a lot.” GRAPHIC DESIGNER JORGE ZEGARRA “He did. But you sure wouldn’t want to play against his wife. Apparently, she once scored 234 points against him with the word ‘quixotic.’” INVENTORS DIGEST LLC “Well, you win most of the time we play. But it’s still fun sharing this time with you.” PUBLISHER LOUIS FOREMAN “Today might be your turn to win, Mom. -

Mids Try to Bounce Back from Heartbreaking Loss

NAVY SPORTS INFORMATION Football Contact: Scott Strasemeier Assistant AD / Sports Information Office Phone: 410-293-8775 Fax: 410-293-8954 Email: [email protected] Navy Sports Information • Ricketts Hall • 566 Brownson Road • Annapolis, MD 21402 Website: www.navysports.com Navy Schedule... Game Information... Date Opponent Time Date: September 10, 2005 Time: 6:00 p.m. (EDT) Sept. 3 vs. Maryland# (CSTV) L, 23-20 Place: Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium (34,500) Sept. 10 Stanford (CSTV) 6:00 pm City: Annapolis, Md. Sept. 24 at Rice 8:00 pm Records: N avy (0-1), S t a n fo rd (0-0) Oct. 1 at Duke TBA Television: College Sports Te l evision (Tom McCart hy and Ray Lucas); Oct. 8 Air Force (CSTV) 1:30 pm HDNet (Pete Medhurst and Astor Heave n ) Oct. 15 Kent State (CSTV) 1:30 pm Radio: Navy Radio Network — Bob Socci (PxP), Omar Nelson Oct. 29 at Rutgers TBA (Color) and John Feinstein (Analysis) Nov. 5 Tulane (HC-CSTV) 1:30 pm Internet: w w w. n av y s p o rts.com (Gametracker and links to audio) Nov. 12 at Notre Dame (NBC) 1:00 pm Series: Navy leads 1-0-1 Streak: Tied-1 Nov. 19 Temple (CSTV) 1:30 pm Dec. 3 vs.Army$ (CBS) 2:30 pm Home games in bold. # — M&T Bank Stadium (Baltimore, Md.) Mids Try To Bounce Back From $ — Lincoln Financial Field (Philadelphia, Pa.) Heartbreaking Loss... Stanford Schedule... Date Opponent Time Game Data... Sept. 10 at Navy (CSTV) 6:00 pm Navy (0-1) will play host to a Pac-10 school at Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium (34,000) for Sept. -

Boston-Denver

BOSTON -D ENVER SERIES HISTORY SERIES BREAKDOWN The Patriots and Broncos will meet (Including Playoffs) for the 43rd time in series history and Overall Record .................... 16-26 (Including 0-2 in playoffs) for the 16th time in the last 18 years. Record in New England ............................................................. 8-9 The Broncos have won five of the last Record in Denver ............................. 8-17 (Including 0-2 in playoffs) seven regular-season and playoff Total Points in the Series ........................... Denver 977, Patriots 847 contests, but had a three-game Bill Belichick vs. Denver ......................... 3-9 (3-5 with New England) winning streak snapped last season Josh McDaniels vs. New England ............................................... 0-0 on Monday Night Football when the TALE OF THE TAPE Patriots beat Denver 41-7 on October 2009 Regular Season New England Denver 20. Record 3-1 4-0 The Broncos own a 26-16 advantage in the series, including a Divisional Standings 2nd 1st 2-0 mark in the playoffs. New Total Yards Gained 1,504 1,460 England lost a Divisional playoff game Total Offense (Rank) 376.0 (8) 365.0 (9) at Denver during the 1986 and 2005 Rush Offense 102.3(18) 148.0 (4) playoffs. Of the 42 previous games in Pass Offense 273.8 (5) 217.0 (17) the series, 25 have been played in Points Per Game 21.8 (14) 19.8 (19) Denver. The Patriots have played Touchdowns Scored 8 8 more games against the Broncos than Third Down Conversion Pct. 45.8 36.7 any other team that has never been Total Yards Allowed 1,150 959 in New England’s division.