University of California Riverside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This section provides a summary of the Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the proposed Gonzaga Ridge Wind Repowering Project (proposed Project). Included in this summary are areas of known controversy and issues to be resolved, a summary of project alternatives, a summary of all project impacts and associated mitigation measures, and a statement of the ultimate level of significance after mitigation is applied. ES.1 DOCUMENT PURPOSE This EIR was prepared by the California Department of Parks and Recreation (CDPR), as lead agency, to inform decision makers and the public of the potential significant environmental effects associated with the proposed Project. This EIR has been prepared in accordance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) of 1970 (California Public Resources Code, Section 21000 et seq.) and the Guidelines for Implementation of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA Guidelines; 14 CCR 15000 et seq.) published by the Public Resources Agency of the State of California. The purpose of this EIR is to focus the discussion on those potential effects on the environment resulting from implementation of the proposed Project which the lead agency has determined may be significant. Feasible mitigation measures are recommended, when applicable, that could reduce significant environmental impacts or avoid significant environmental impacts. ES.2 PROJECT LOCATION The Project site is located in western Merced County and includes land leased from CDPR located in the eastern portion of Pacheco State Park (Park) on approximately 1,766 acres. The Park is located on State Route 152 (SR-152), that connects two major north-south arteries—Interstate 5 (I-5), which is 16 miles to the east, and U.S. -

SLLPIP EIS/EIR Appendix K: Draft Cultural Resources Report

Appendix K Draft Cultural Resources Report This page left blank intentionally. Cultural Resources Consultants CULTURAL RESOURCES REPORT FOR THE SAN LUIS LOW POINT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT, MERCED AND SANTA CLARA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Christopher Park, AICP CDM Smith 2295 Gateway Oaks Drive Sacramento, California 95883 Prepared by: Lisa Holm, PhD, John Holson, MA, Marc Greenberg, MA, Mary O’Neill, BA, Elena Reese, MA, Shanna Streich, MA, Christopher Peske, BA, Edward de Haro, BA, and Josh Varkel, BA Pacific Legacy, Inc. Bay Area Division 900 Modoc Avenue Berkeley, California 94707 Project No. 3459-02 Total Current Project Area for the Lower San Felipe Intake Alternative, the Combination Alternative, the Treatment Alternative, and the San Luis Reservoir Expansion Alternative: 51,475 Acres USGS 7.5’ Topographic Quadrangle Maps: Calaveras Reservoir (1980), Crevison Peak (2015), Cupertino (1991), Los Banos Valley (2015), Mariposa Peak (2015), Pacheco Pass (1971), San Jose East (1980), San Jose West (1980), San Luis Dam (1969), and Santa Teresa Hills (1981), California December 2018 This page left blank intentionally. Confidentiality Statements Archaeological remains and historic period built environment resources can be damaged or destroyed through uncontrolled public disclosure of information regarding their location. This document contains sensitive information regarding the nature and location of cultural resources, which should not be disclosed to unauthorized persons. Information regarding the location, character or ownership of certain historic properties may be exempt from public disclosure pursuant to the National Historic Preservation Act (54 USC 300101 et seq.) and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (Public Law 96-95 and amendments). In addition, access to such information is restricted by law, pursuant to Section 6254.10 of the California State Government Code. -

Ethnohistory and Ethnogeography of the Coast Miwok and Their Neighbors, 1783-1840

ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGEOGRAPHY OF THE COAST MIWOK AND THEIR NEIGHBORS, 1783-1840 by Randall Milliken Technical Paper presented to: National Park Service, Golden Gate NRA Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division Building 101, Fort Mason San Francisco, California Prepared by: Archaeological/Historical Consultants 609 Aileen Street Oakland, California 94609 June 2009 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report documents the locations of Spanish-contact period Coast Miwok regional and local communities in lands of present Marin and Sonoma counties, California. Furthermore, it documents previously unavailable information about those Coast Miwok communities as they struggled to survive and reform themselves within the context of the Franciscan missions between 1783 and 1840. Supplementary information is provided about neighboring Southern Pomo-speaking communities to the north during the same time period. The staff of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) commissioned this study of the early native people of the Marin Peninsula upon recommendation from the report’s author. He had found that he was amassing a large amount of new information about the early Coast Miwoks at Mission Dolores in San Francisco while he was conducting a GGNRA-funded study of the Ramaytush Ohlone-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. The original scope of work for this study called for the analysis and synthesis of sources identifying the Coast Miwok tribal communities that inhabited GGNRA parklands in Marin County prior to Spanish colonization. In addition, it asked for the documentation of cultural ties between those earlier native people and the members of the present-day community of Coast Miwok. The geographic area studied here reaches far to the north of GGNRA lands on the Marin Peninsula to encompass all lands inhabited by Coast Miwoks, as well as lands inhabited by Pomos who intermarried with them at Mission San Rafael. -

Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, Circa 1852-1904

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb109nb422 Online items available Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Finding Aid written by Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Documents BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM 1 Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in Cali... Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt. Date Completed: March 2008 © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Documents pertaining to the adjudication of private land claims in California Date (inclusive): circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892 Microfilm: BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM Creators : United States. District Court (California) Extent: Number of containers: 857 Cases. 876 Portfolios. 6 volumes (linear feet: Approximately 75)Microfilm: 200 reels10 digital objects (1494 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: In 1851 the U.S. -

How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, and the Colonial Roots of California, 1846 – 1879

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, And The Colonial Roots Of California, 1846 – 1879 Camille Alexandrite Suárez University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Suárez, Camille Alexandrite, "How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, And The Colonial Roots Of California, 1846 – 1879" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3491. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3491 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3491 For more information, please contact [email protected]. How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, And The Colonial Roots Of California, 1846 – 1879 Abstract The construction of California as an American state was a colonial project premised upon Indigenous removal, state-supported land dispossession, the perpetuation of unfree labor systems and legal, race- based discrimination alongside successful Anglo-American settlement. This dissertation, entitled “How the West was Won: Race, Citizenship, and the Colonial Roots of California, 1849 - 1879” argues that the incorporation of California and its diverse peoples into the U.S. depended on processes of colonization that produced and justified an adaptable acialr hierarchy that protected white privilege and supported a racially-exclusive conception of citizenship. In the first section, I trace how the California Constitution and federal and state legislation violated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This legal system empowered Anglo-American migrants seeking territorial, political, and economic control of the region by allowing for the dispossession of Californio and Indigenous communities and legal discrimination against Californio, Indigenous, Black, and Chinese persons. -

San Luis Reservoir

MISSION STATEMENTS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR The Mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation's natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS & RECREATION To provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping to preserve the state's extraordinary biological diversity, protecting its most valued natural and cultural resources, and creating opportunities for high-quality outdoor recreation. San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area Draft Resource Management Plan / General Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement / Revised Draft Environmental Impact Report This document contains a joint Draft Resource Management Plan (RMP)/General Plan (GP) and Draft Environmental Impact Statement/Revised Draft Environmental Impact Report (Draft EIS/EIR) for the San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area (SRA) and adjacent lands owned by the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) and managed by the California Department of Parks and Recreation (also known as California State Parks, or CSP), California Department of Water Resources (DWR), and California Department of Fish and Game (DFG). This document also contains policies, in the form of goals and guidelines, that relate to the project area and a description of the desired future condition of project area lands and waters for recreation and resource use and management. The purpose of the Draft EIS/EIR is to help Reclamation and CSP select a preferred alternative for implementing the RMP/GP. -

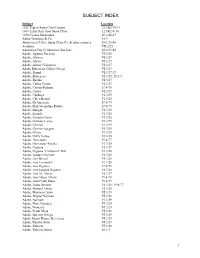

Subject Index

SUBJECT INDEX Subject Location 1852 Trip to Santa Clara County 12:1&2/10-11 1868 Letter Sent from Santa Clara 12:1&2/8-10 1890 Census Substitutes 26:2/46-47 Abbot-Downing & Co. I:1/9 Abstracts of Titles, Santa Clara Co. & other counties 38:1/29-40 Acadians VII:3/25 Admission Day Celebration, San Jose 22:2/39-40 Adobe, Agustin Narvaez VI:3/28 Adobe, Alvirez VI:3/29 Adobe, Alviso VI:3/27 Adobe, Alviso (Valencia) VI:3/27 Adobe Bakeoven, Gilroy-Ortega VI:3/29 Adobe, Bernal VI:3/27-29 Adobe, Berreyesa VI:3/29; 20:1/3 Adobe, Buelna VI:3/27 Adobe, Carlos Castro VI:3/29 Adobe, Carson-Perham 19:4/78 Adobe, Castro VI:3/29 Adobe, Chaboya VI:3/29 Adobe, Chico Bernal VI:3/28 Adobe, De Quevedo 19:4/79 Adobe, Don Secundino Robles 19:4/79 Adobe, Enright VI:3/28 Adobe, Estrada VI:3/28 Adobe, Estrada-Castro VI:3/28 Adobe, Galindo-Larios VI:3/29 Adobe, German VI:3/29 Adobe, German-Sargent VI:3/29 Adobe, Gilroy VI:3/29 Adobe, Hall's Valley VI:3/28 Adobe, Hernandez 19:4/77 Adobe, Hernandez-Peralta VI:3/28 Adobe, Higuera VI:3/27 Adobe, Higuera "California" Mill VI:3/28 Adobe, Joaquin Narvaez VI:3/28 Adobe, Jose Bernal VI:3/28 Adobe, Jose Fernandez VI:3/28 Adobe, Jose Higuera 19:4/78 Adobe, Jose Joaquin Higuera VI:3/28 Adobe, Jose M. Alviso VI:3/27 Adobe, Jose Maria Alviso 19:4/78 Adobe, Juan Prado Mesa 19:4/77 Adobe, Juana Briones VI:3/28; 19:4/77 Adobe, Manuel Alviso VI:3/28 Adobe, Mariano Castro VI:3/29 Adobe, Miguel Narvaez VI:3/28 Adobe, Narvaez VI:3/29 Adobe, New Almaden VI:3/29 Adobe, Pomeroy VI:3/29 Adobe, Prado Mesa VI:3/28 Adobe, Quentin Ortega VI:3/29 -

San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area EA 07-45

Photo by Roy W. Martin Draft Environmental Assessment Restroom Replacement and Trail Construction - San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area EA 07-45 U.S Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid-Pacific Region South Central California Area Office Fresno, California May 2007 Contents Page Chapter 1: Purpose and Need for Action ................................................. 5 1.1 Background ................................................................................. 5 1.2 Purpose and Need....................................................................... 8 1.3 Scope ………………………………………………………………… 8 1.4 Potential Issues ........................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Proposed Action and Alternatives ......................................... 8 2.1 Alternative 1 (No Action Alternative) ............................................ 8 2.2 Common Aspects of all Action Alternatives 2 through 5............... 9 2.3 Alternative 2 – Trail Construction Only......................................... 9 2.4 Alternative 3 – Basalt Use Area Restroom Replacement Only..... 13 2.5 Alternative 4 – San Luis Creek Day Use Area Restroom Replacement Only .............................................................................................. 15 2.6 Alternative 5 – Complete 1.5 Miles of Trail and Replace the Restroom Facilities at the Above Two Locations Specified Above Project (Proposed Action) .............................................................................................. 15 Chapter -

UFW Office of the President: Arturo Rodriguez Records 69.5 Linear Feet (69 SB, 1 MB) 1938-1997, Bulk 1976-1996

UFW Office of the President: Arturo Rodriguez Records 69.5 linear feet (69 SB, 1 MB) 1938-1997, bulk 1976-1996 Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Byron S. Collier on July 22, 2011. Accession Number: LR002199 Creator: UFW President’s Office Acquisition: The records of the UFW Office of the President: Arturo Rodriguez Records were placed in the Walter P. Reuther Library in June 1991 and March 1998 and opened for research in August 2011. Language: Material in English and in Spanish. Access: Records are open for research. Items in vault are available at the discretion of the archives. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Restrictions: Researchers may encounter records of a sensitive nature – personnel files, case records and those involving investigations, legal and other private matters. Privacy laws and restrictions imposed by the Reuther Library prohibit the use of names and other personal information, which might identify an individual, except with written permission from the Director and/or the donor. Notes: Citation style: “UFW Office of the President: Arturo Rodriguez Records, Box [#], Folder [#], Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Related Material: United Farm Workers of America records collections at the Walter P. Reuther Library. Box 70: Audio/video tapes were transferred to the Reuther Library’s Audiovisual Department. Original signed letters to Dolores Huerta in Box 21: 20-21 have been moved to the vault. PLEASE NOTE: Material in this collection has been arranged by series ONLY. Folders are not arranged within each series – we have provided an inventory based on their original order. -

San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area Final Resource Management Plan / General Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement

2. Existing Conditions 2 Existing Conditions This chapter summarizes the existing land uses, resources, existing facilities, local and regional plans, socioeconomic setting, and visitor uses that will influence the management, operations, and visitor experiences at the Plan Area. This information will provide the baseline data for developing the goals and guidelines for the management policies of the Plan and will serve as the affected environment and environmental setting for the purpose of environmental review. 2.1 Land Use 2.1.1 Surrounding Land Uses / Regional Context The Plan Area is surrounded by a variety of land uses. Residential and commercial uses exist nearby in the unincorporated community of Santa Nella to the northeast of O’Neill Forebay. Lands to the southeast of the Plan Area between San Luis Reservoir and Los Banos Creek Reservoir include privately owned ranchlands, agricultural lands, an electrical substation, and scattered nonresidential uses. The San Joaquin Valley National Cemetery is northeast of O’Neill Forebay. Immediately west of San Luis Reservoir is Pacheco State Park, owned by CSP. DFW properties are located north of San Luis Reservoir and east of the O’Neill Forebay. The nearest incorporated cities are Los Banos, approximately 13 miles to the east; Gustine, approximately 18 miles to the north; and Gilroy, approximately 38 miles to the west. Santa Nella lies 2 miles to the northeast. Other nearby communities include Volta and Hollister. The Villages of Laguna San Luis, south of O’Neill Forebay and east of San Luis Reservoir, is an approved community plan that has not been constructed. Agua Fria is another planned community that could be developed south of and adjacent to the Villages of Laguna San Luis. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Cultural Resources

Chapter 17: Cultural Resources Chapter 17 1 Cultural Resources 2 17.1 Introduction 3 Cultural resources are defined as prehistoric and historic archaeological sites, 4 architectural features (e.g., buildings, bridges, flumes, trestles, railroads), and 5 traditional cultural properties. However, the focus of this chapter is more on 6 cultural resources than historic properties. 7 This chapter describes the known existing cultural resources conditions in the 8 study area and the potential changes that could occur as a result of implementing 9 the alternatives evaluated in this Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). 10 Implementation of the alternatives could affect cultural and historic resources 11 through potential changes in the operation of the Central Valley Project (CVP) 12 and State Water Project (SWP). Changes in CVP and SWP operations could 13 increase the frequency and duration of low-elevation reservoir conditions that 14 would increase the time of exposure of inundated cultural resources within 15 reservoirs that store CVP and SWP water. Changes in CVP and SWP operations 16 also could reduce water supply availability to agricultural lands, and those lands 17 could be subject to land use changes that could increase disturbances of cultural 18 resources if present. 19 17.2 Regulatory Environment and Compliance 20 Requirements 21 Potential actions that could be implemented under the alternatives evaluated in 22 this EIS could affect reservoirs, streams, and lands served by CVP and SWP 23 water supplies located on lands with cultural resources. Actions implemented, 24 funded, or approved by Federal and state agencies would need to be compliant 25 with appropriate Federal and state agency policies and regulations, as summarized 26 in Chapter 4, Approach to Environmental Analyses.