Subtitling: an Analysis of the Process of Creating Swedish Subtitles for a National Geographic Documentary About Mixed Martial Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BISPING: Barnett Needs to Push the Pace Vs. Nelson

FS1 UFC TONIGHT Show Quotes – 9/23/15 BISPING: Barnett Needs To Push The Pace Vs. Nelson Florian: “Uriah Hall Is Too Dangerous To Just Stand and Trade With” LOS ANGELES – UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian and guest host Michael Bisping break down the upcoming FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BARNETT VS. NELSON. Karyn Bryant and Ariel Helwani add reports. UFC TONIGHT guest host Michael Bisping on how Josh Barnett can beat Roy Nelson: “Josh needs to not get hit by the right hand of Roy. He needs to push the pace of the fight, move forward, and push Roy up against fence and brutalize him with knees and elbows like he did with Frank Mir. Most of his finishes came from the clinch position. He finishes fights against the fence. He did that against Frank Mir.” UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian on Barnett avoiding Nelson’s knock out power: “Josh doesn’t want to be on the outside where Roy’s right hand can get him. He wants to be on the inside. He’s been busy on the submission circuit. He’s dangerous on the mat and that’s where he wants to get Roy.” Bisping on how Nelson should fight Barnett: “What Roy can’t get is predictable. If he just tries to throw the big right hand, Barnett is going to see it coming. Roy has to mix up his striking. I’m not sure he’s going to go for takedowns. But he has to mix his striking. His right hand and left hooks, to keep Josh at bay.” Florian on Nelson mixing up his strikes: “The knock on Nelson is his lack of evolution. -

KING of the RING – Muay Thai Rules

WIPU – World independent Promoters Union in association with worldwide promoters, specialized magazines & TV p r e s e n t s WORLD INDEPENDANT ORIENTAL PRO BOXING & MMA STAR RANKINGS OPEN SUPER HEAVYWEIGHT +105 kg ( +232 lbs ) KING OF THE RING – full Muay Thai rules 1. Semmy '' HIGH TOWER '' Schilt ( NL ) = 964 pts LLOYD VAN DAMS ( NL ) = 289 pts 2. Peter '' LUMBER JACK '' Aerts ( NL ) = 616 pts Venice ( ITA ), 29.05.2004. 3. Alistar Overeem ( NL ) = 524 pts KING OF THE RING – Shoot boxing rules 4. Jerome '' GERONIMO '' Lebanner ( FRA ) = 477 pts - 5. Alexei '' SCORPION '' Ignashov ( BLR ) = 409 pts KING OF THE RING – Thai boxing rules 6. Anderson '' Bradock '' Silva ( BRA ) = 344 pts TONY GREGORY ( FRA ) = 398 pts 7. '' MIGHTY MO '' Siligia ( USA ) = 310 pts Auckland ( NZ ), 09.02.2008. 8. Daniel Ghita ( ROM ) = 289 pts KING OF THE RING – Japanese/K1 rules 9. Alexandre Pitchkounov ( RUS ) = 236 pts - 10. Mladen Brestovac ( CRO ) = 232 pts KING OF THE RING – Oriental Kick rules 11. Bjorn '' THE ROCK '' Bregy ( CH ) = 231 pts STIPAN RADIĆ ( CRO ) = 264 pts 12. Konstantins Gluhovs ( LAT ) = 205 pts Johanesburg ( RSA ), 14.10.2006. 13. Rico Verhoeven ( NL ) = 182 pts Upcoming fights 14. Peter '' BIG CHIEF '' Graham ( AUS ) = 177 pts 15. Ben Edwards ( AUS ) = 161 pts 16. Patrice Quarteron ( FRA ) = 147 pts 17. Patrick Barry ( USA ) = 140 pts 18. Mark Hunt ( NZ ) = 115 pts 19. Paula Mataele ( NZ ) = 105 pts 20. Fabiano Goncalves ( BRA ) = 89 pts WIPU – World independent Promoters Union in association with worldwide promoters, specialized magazines & TV p r e s e n t s WORLD INDEPENDANT ORIENTAL PRO BOXING & MMA STAR RANKINGS HEAVYWEIGHT – 105 kg ( 232 lbs ) KING OF THE RING – full Muay Thai rules CHEIK KONGO (FRA) = 260 pts 1. -

Hdnet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012

HDNet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012 Monday January 30, 2012 3:30 PM ET / 12:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT HDNet Fights Visions of New York City DREAM New Year! 2011 - Former PRIDE Heavyweight Champion Fedor Emelianenko meets New York in all its striking juxtapositions of nature and modern progress, geometry and geog- Olympic Judo Gold Medalist Satoshi Ishii. Shinya Aoki defends the DREAM Lightweight Title raphy - the harbor from Lady Liberty’s perspective to Central Park as the birds experience it. against Satoru Kitaoka. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Cheers Prison Break Diane Meets Mom - Diane’s nervous about meeting Frasier’s mother Hester, who’s a Riots, Drills and the Devil - Michael’s ploy to buy some work time by prompting a cellblock renowned psychologist. Hester’s pleasant during dinner, but when Frasier leaves them alone, lockdown leads to a full-scale riot; Nick convinces Veronica that he really does want to help she threatens to kill Diane if she continues to interfere with her son’s life. her; and Kellerman hires an inmate to kill Lincoln. 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT Cheers JAG An American Family - Carla’s ex-husband returns with his new bride, demanding custody of Offensive Action - In a P-3 Squadron over the Pacific Ocean, Cmdr. O’Neil hounds Lt. Kersey their oldest son. The normally feisty Carla shocks everyone at the bar when she agrees to the during a mission. -

The Three Pillars of Catch in Japan Pro-Wrestling"

ne go g e in ith v rn ve w ha a a d le o le h ho u itt to t er y w fe ly l c m ft a s d nt is gi e a . M r ry n re e lo y se n st he ve a a er r an 't pa e ot t ts pp th o sn a W d u gh a t - ad g e J e e , b fi n bu ve h in o to th nc n is ka , ro is tl D k n e pa . H ? ed p th es ac i flu a e d n to t r b ch in J er K? e ha -W at d/ to h pp ce - t ro C e n e a n P n in ur nc h de te n pa ra et e vi la o a t r id e cu e J id ev pe nc in d e s e A ttl d flu M li an in M d US to n n k , a i ac an g ch b z lin at it do st C ht ki e n g Ri r i ou d -W ed r le ro in , b st P ra pe re n T ro w ow u , s E an hi p d on Ja te ti ar iza st n ga or ; an ap nt J e to ud h st tc a o so t G al h y ug el , ro lik rs B t e os ch ch d ry m ot a A ve G te m 't of y ro n to at an f e as t d m ng th w o e d ni g n a g oy a ar tin o ur he tr h le si n m n s sz g vi a Ki e de e in d ig s h t f Th d n W s y ; w go t o lu a in on a d e it n nc el it si S lle h P e is i nt P a ki n e ud h . -

Brandon Vera, Et Al. V. Zuffa, LLC, D/B/A Ultimate

Case5:14-cv-05621 Document1 Filed12/24/14 Page1 of 63 1 Joseph R. Saveri (State Bar No. 130064) Joshua P. Davis (State Bar No. 193254) 2 Andrew M. Purdy (State Bar No. 261912) Kevin E. Rayhill (State Bar No. 267496) 3 JOSEPH SAVERI LAW FIRM, INC. 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 625 4 San Francisco, California 94111 Telephone: (415) 500-6800 5 Facsimile: (415) 395-9940 [email protected] 6 [email protected] [email protected] 7 [email protected] 8 Benjamin D. Brown (State Bar No. 202545) Hiba Hafiz (pro hac vice pending) 9 COHEN MILSTEIN SELLERS & TOLL, PLLC 1100 New York Ave., N.W., Suite 500, East Tower 10 Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 408-4600 11 Facsimile: (202) 408 4699 [email protected] 12 [email protected] 13 Eric L. Cramer (pro hac vice pending) Michael Dell’Angelo (pro hac vice pending) 14 BERGER & MONTAGUE, P.C. 1622 Locust Street 15 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Telephone: (215) 875-3000 16 Facsimile: (215) 875-4604 [email protected] 17 [email protected] 18 Attorneys for Individual and Representative Plaintiffs Brandon Vera and Pablo Garza 19 [Additional Counsel Listed on Signature Page] 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 21 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN JOSE DIVISION 22 Brandon Vera and Pablo Garza, on behalf of Case No. 23 themselves and all others similarly situated, 24 Plaintiffs, ANTITRUST CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 25 v. 26 Zuffa, LLC, d/b/a Ultimate Fighting DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Championship and UFC, 27 Defendant. 28 30 Case No. 31 ANTITRUST CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 32 Case5:14-cv-05621 Document1 Filed12/24/14 Page2 of 63 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 3 I. -

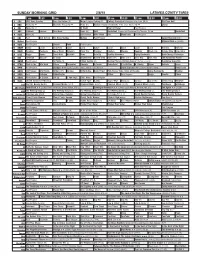

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Nevada

Case 2:15-cv-01045-RFB-PAL Document 518 Filed 02/16/18 Page 1 of 46 1 Eric L. Cramer (Pro Hac Vice) Michael Dell’Angelo (Pro Hac Vice) 2 Patrick F. Madden (Pro Hac Vice) Mark R. Suter (Pro Hac Vice) 3 BERGER & MONTAGUE, P.C. 4 1622 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 5 Telephone: (215) 875-3000 Facsimile: (215) 875-4604 6 [email protected] 7 [email protected] [email protected] 8 [email protected] 9 Attorneys for Individual and Representative Plaintiffs Cung Le, Nathan Quarry, Jon Fitch, Luis Javier 10 Vazquez, Brandon Vera, and Kyle Kingsbury 11 (Additional counsel appear on signature page) 12 13 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEVADA 14 15 Cung Le, Nathan Quarry, Jon Fitch, Brandon Case No.: 2:15-cv-01045-RFB-PAL Vera, Luis Javier Vazquez, and Kyle Kingsbury, 16 on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR CLASS 17 CERTIFICATION 18 Plaintiffs, 19 v. 20 Zuffa, LLC, d/b/a Ultimate Fighting 21 Championship and UFC, 22 Defendant. 23 24 25 26 27 28 Case No.: 2:15-cv-01045-RFB-(PAL) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR CLASS CERTIFICATION PUBLIC COPY-REDACTED Case 2:15-cv-01045-RFB-PAL Document 518 Filed 02/16/18 Page 2 of 46 1 NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION 2 TO ALL PARTIES AND ATTORNEYS OF RECORD: 3 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that Plaintiffs Cung Le, Nathan Quarry, Jon Fitch, Brandon Vera, Luis 4 Javier Vazquez, and Kyle Kingsbury (“Plaintiffs”) will and hereby do move the Court, pursuant to 5 Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23, for an order certifying this action as a class action and appointing 6 Co-Lead and Liaison Class Counsel. -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University. -

Pop Gym Zine #2

Forward (March 2019) Hello! I don’t know if this is the your second issue, if this is your first time picking up our zine, your second read-through of the second issue, your first time reading both issues backwards (I don’t know your life), but we are so happy to have you here on this page our second-ever zine! As we mentioned before, this zine is filled with stories and art from a bunch of folks who do martial arts, self-de- fense, health, and more!. Not so much a “how to” guide, but more a collection of narratives from folks who have found and made a place for themselves within the Martial Arts and Movement world, and how their practices have changed them. We hope that this zine (also featuring some cool resources) will inspire folks to pick up some self-de- fense of their own, even if it means going to your local self-defense workshop whenever you have a free moment. As we go into our third year of existence, we just can’t wait for all the cool events we have coming up: new spaces, new friends, old friends, new opportunities to share self-defense skills with folks and communities we love to work with. We’re crossing our fingers because of some big plans we have coming up that could take this project to the NEXT LEVEL, and we can’t wait for all the cool things this can bring. In any case, hope you enjoy the works in this zine. Wher- ever you are in your life (or wherever we are in the future) hopefully this zine can be of some use to you in some way. -

Ufc® 165 Fight Between Jon Jones and Alexander Gustafsson to Be Inducted Into Ufc® Hall of Fame

UFC® 165 FIGHT BETWEEN JON JONES AND ALEXANDER GUSTAFSSON TO BE INDUCTED INTO UFC® HALL OF FAME Las Vegas – UFC® today announced that the classic 2013 fight between UFC light heavyweight champion Jon Jones and Alexander Gustafsson will be inducted into the UFC Hall of Fame’s ‘Fight Wing’ as part of the Class of 2020. The 2020 UFC Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, presented by Toyo Tires®, will take place on Thursday, July 9, at The Pearl at Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas. The event will be streamed live on UFC FIGHT PASS®. “Going into the first Jones vs. Gustafsson fight, fans and media didn’t care about the fight, because they didn’t believe Gustafsson deserved a title shot, and this thing ended up being the greatest light heavyweight title fight in UFC history,” UFC President Dana White said. “To be there and watch it live was amazing. It was an incredible fight and both athletes gave everything they had for all five rounds. This fight was such a classic it was named the 2013 Fight of the Year and will always be considered one of the greatest fights in combat sports history. This fight showed what a true champion Jon Jones was, as this was the first time he was taken into deep waters and truly tested. This fight also put Gustafsson on the map and showed his true potential. Congratulations to Jon Jones and Alexander Gustafsson on being inducted into the UFC Hall of Fame ‘Fight Wing’ for such an epic fight.” As the main event of UFC® 165: JONES vs. -

Outside the Cage: the Political Campaign to Destroy Mixed Martial Arts

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2013 Outside The Cage: The Political Campaign To Destroy Mixed Martial Arts Andrew Doeg University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Doeg, Andrew, "Outside The Cage: The Political Campaign To Destroy Mixed Martial Arts" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2530. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2530 OUTSIDE THE CAGE: THE CAMPAIGN TO DESTROY MIXED MARTIAL ARTS By ANDREW DOEG B.A. University of Central Florida, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 © 2013 Andrew Doeg ii ABSTRACT This is an early history of Mixed Martial Arts in America. It focuses primarily on the political campaign to ban the sport in the 1990s and the repercussions that campaign had on MMA itself. Furthermore, it examines the censorship of music and video games in the 1990s. The central argument of this work is that the political campaign to ban Mixed Martial Arts was part of a larger political movement to censor violent entertainment. -

Sea Fighters

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY CIR CULATION DEP ARTM EN T CHILDREN’ S ROOM Entrance on 42nd Street Books circulate for four weeks ( 28 days ) unless “ ” “ ” stamped 1 week or 2 weeks . No renewals are allowed . A fine will be charged for each overdue book at the rate of 5 cents per calendar day for adult books and 2 cents per calendar day for chil ’ dren s books . m—n m m.w - THE MACMILLAN COMP ANY NE W Y OR K BOS TON CHICAG O D ALLAS ATLANTA S AN FRANCIS CO I m N m A A co. M CM LL , ' ' ‘ LOND ON 0 BOMBAY CALCU I I A ME LBOURNE H E A MI AN F AN ADA T M C LL CO. O C TORONTO sE A F I G H T E R S NAVY YARNS OF THE GREAT WAR BY E L WARR N H . MI LER Namarl: E THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1920 All Right: Reserved COPY R IGHT, 1920, B r THE MACM ILLAN C OMPANY t and electrot ed Published ctober 1920. Se up yp . O . 1 0 E ( 59 70 ( l H fb ; 570 %o CONTENT S PEAS E OF TH E NAVY BR OTH ER TO I CARU S TH E S ALU TE H IS B IT — 10 0 S . C. 3 TH E D EF E N S E TH E H A N DS OF TH E CAP TAI N L IVE B AI T TH E PLAI N PAT H OF DU TV S EA FIGH TERS PEAS E OF TH E NAVY P afe a TH E eases N v y people .