Resisting the Neoliberal Girl Power Agent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCHOOL GARDENS.L

CHAPTEIl XI. SCHOOL GARDENS.l By E. G.L'G, 'I'riptis, Thuringia, Germany. C01drnts.-IIistorical Review-Sites and arrangement of Rchool gatdcns-s-Dilterent Rections of fkhool gardens-::\Ianagement-Instruction in School gardens-E\lucu- tional and Economic Significance of School gardens. 1. DISTOIlY. Rchool gardens, in the narrow sense of the term, are a very modern institution; but when considered as including all gardens serving the purpose of instruction, the expression ol Ben Akiba may be indorsed, "there is nothing new under the SUIl," for in a comprehensive sense, school gardens cease to be a modern institution. His- tory teaches that the great Persian King Cyrus the Elder ( 559-5~ B. C.) laid out the first school gardens in Persia, in which the sons of noblemen were instruct ·(1 ill hor- ticulture. King Solomon (1015 B. C.) likewise possessed extensive gardens ill which all kinds of plants were kept, probably for purposes of instruction as well as orna- ment, "from the cedar tree that is in Lebanon even unto the hyssop that springoth out of the wall." The botanical gardens of Italian and other univer -ities belong to school gardens in the broader acceptation of the term. The first to establish a garden of this kind was Gaspar de Gabriel, a wealthy Italian nobleman, who, in 1525 A. D., laid out the first one in Tuscany. Many Italian cities, Venice, Milan, and Naples followed this ex- ample. Pope Pius V (1566-1572) cstabli hed one in Bologna, and Duke Franci . of Tuscany (1574-1584) one in Florence. At that time, almost every important city in Italy possessed its botanical garden. -

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "Say Aprayer"9-4: - the New Single

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "say aprayer"9-4: - the new single. Your prayers are answered. Breathe's gold debut album All That Jazz delivered three Top 10 singles, two #1 AC tracks, and songwriters David Glasper and Marcus Lillington jumped onto Billboard's list of Top Songwriters of 1989. "Say A Prayer" is the first single from Breathe's much -anticipated new album Peace Of Mind. Produced by Bob Sargeant and Breathe Mixed by Julian Mendelsohn Additional Production and Remix by Daniel Abraham for White Falcon Productions Management: Jonny Too Bad and Paul King RECORDS I990 A&M Record, loc. All rights reserved_ the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A GLANCE * Indicates Tie MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MICHAEL BOLTON JOHNNY GILL MICHAEL BOLTON MATRACA BERG Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) Fairweather Friend (Motown) Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) The Things You Left Undone (RCA) BREATHE QUINCY JONES featuring SIEDAH M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Say A Prayer (A&M) GARRETT Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) LISA STANSFIELD I Don't Go For That ((west/ BASIA HANK WILLIAMS, JR. This Is The Right Time (Arista) Warner Bros.) Until You Come Back To Me (Epic) Man To Man (Warner Bros./Curb) TRACIE SPENCER Save Your Love (Capitol) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS SAMUELLE M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Unchained Melody (Verve/Polydor) So You Like What You See (Atlantic) Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) 1IrPHIL COLLINS PEBBLES ePHIL COLLINS goGARTH BROOKS Something Happened 1 -

1995-1996 Literary Magazine

á Shabash AMERICAN EMBASSY MIDDLE SCHOOL 1995-1996 LITERARY MAGAZINE Produced by Ms. Lundsteen’s English Class: Marco Acciarri Youn Joung Choi Bassem Amin Rohan Jetley Erin Brand Tara Lowen-Ault Grace Calma Daniel Luntzel Ajay Chand - Zoe Manickam With special thanks to Mrs. Kochar for her patience and guidance. Cover Design: Tara Lowen-Ault "" "7'_"'""’/Y"*"‘ ' F! f'\ O f O O f-\ ü Ö O o o o O O ____\. O o O . Q o ° '\ . '.-'.. n, . _',':'. '- -.'.` Q; Z / \ / The Handsome Toad A Trip Down Memory Lane Once upon a time a ugly princess was playing soccer with a solid gold ball in her garden. She slipped and the ball went flying up into the air When I was four, and landed into a nearby lake. “lt’s a throw in!” the umpire called out. My Dad was working in England, The princess went to get the ball but soon He was offered a job in Oman, realized that the ball had sunk. Then in spite of He went for the interview in the morning, herself she saw a toad swimming. I told him,“Daddy wear this tie.lt is fashion.” She said to the toad,”lf you go get my gold ball, He wore it. you can sleep in my bed tonight.” ' He got back in the evening. At first the toad did not think it was a good idea I asked “Daddy are we going to Oman?” but after all she was the princess so she could "Yes,” he said. execute him. So the toad agreed. -

Steve Pamon President & Chief Operating Officer Parkwood Entertainment

Steve Pamon President & Chief Operating Officer Parkwood Entertainment Launch With GS External Advisory Council Steve Pamon is the President and Chief Operating Officer of global entertainer Beyoncé’s management and production company, Parkwood Entertainment. In his time at Parkwood Entertainment, the team has continued its history of critical and commercial success in the media, entertainment, and consumer products business, as evident in the Super Bowl 50 Halftime Show, Lemonade visual album, 22 Days Nutrition, The Formation World Tour, Coachella Homecoming, On the Run II world tour, Everything is Love album, Global Citizen Africa Festival, Adidas / Ivy Park partnership, Disney’s The Lion King: The Gift album, among many others. In addition, his team manages the careers of rapper/songwriter, Ingrid and actresses/musicians, Chloe x Halle. Prior to joining Parkwood Entertainment, Pamon was the head of sports and entertainment marketing for JPMorgan Chase, where he led a team responsible for the ongoing operations around the bank’s broad sponsorship portfolio, including Madison Square Garden (NY Knicks & NY Rangers), NY Jets, NY Giants, Radio City Music Hall, The Rockettes, The US Open Tennis Tournament, Chicago Theater, and the Los Angeles Forum. Before joining JPMC, Pamon was the Vice President of Strategy and New Business Development for the National Football League. He also served as the Senior Vice President and General Manager of HBO's digital distribution. His career began with stints at Merrill Lynch, Citigroup, McKinsey & Co., and Time Warner. Outside of his full-time role, Pamon recently completed a 10 year term as a board member of New York Road Runners ("NYRR"), a non-profit organization that produces more than 100 sports events each year - including the famed New York City Marathon. -

Top 200 Concert Grosses

2018 YEAR END | TOP 200 CONCERT GROSSES Artist Tickets Sold Artist Tickets Sold Date Facility/Promoter Support Capacity Gross Date Facility/Promoter Support Capacity Gross 07/20/18 Taylor Swift Camila Cabello 165,654 $22,031,385 06/28/18 Eagles/Jimmy Buffett Vince Gill 48,122 $9,055,130 07/21-22 MetLife Stadium Charli XCX 55,218 Coors Field 48,122 East Rutherford, NJ 100% Denver, CO 100% 3 shows Messina Touring Group / AEG Presents 49.50 - 499.50 1 Live Nation 47.00 - 397.00 23 07/26/18 Taylor Swift Camila Cabello 174,764 $21,779,845 08/25/18 Taylor Swift Camila Cabello 56,112 $9,007,179 07/27-28 Gillette Stadium Charli XCX 58,255 Nissan Stadium Charli XCX 56,112 Foxboro, MA 100% Nashville, TN 100% 3 shows Messina Touring Group / AEG Presents 49.50 - 499.50 2 Messina Touring Group / AEG Presents 49.50 - 499.50 24 08/10/18 Taylor Swift Camila Cabello 116,745 $18,089,414 08/24/18 Drake Migos 67,446 $8,992,078 08/11/18 Mercedes-Benz Stadium Charli XCX 58,373 08/25/18 Madison Square Garden Arena Roy Wood$ 16,861 Atlanta, GA 100% 08/27-28 New York, NY 100% 2 shows Messina Touring Group / AEG Presents 49.50 - 499.50 3 4 shows Live Nation 53.50 - 263.50 25 05/18/18 Taylor Swift Camila Cabello 118,084 $16,251,980 06/25/18 U2 55,575 $8,705,673 05/19/18 Rose Bowl Stadium Charli XCX 59,042 06/26/18 Madison Square Garden Arena 18,525 Pasadena, CA 100% 07/01/18 New York, NY 100% 2 shows Messina Touring Group / AEG Presents 49.50 - 499.50 4 3 shows Live Nation Global Touring 41.00 - 325.00 26 10/05/18 Taylor Swift Camila Cabello 105,002 $15,006,157 -

Susan J. Douglas, Enlightened Sexism: the Seductive Message That Feminism's Work Is Done, New York: Times Books, 2010, 368 Pp, $26.00 (Hardcover).1

International Journal of Communication 5 (2011), Book Review 639–643 1932–8036/2011BKR0639 Susan J. Douglas, Enlightened Sexism: The Seductive Message that Feminism's Work is Done, New York: Times Books, 2010, 368 pp, $26.00 (hardcover).1 Reviewed by Umayyah Cable University of Southern California With biting wit, Susan Douglas’ Enlightened Sexism: The Seductive Message that Feminism's Work is Done sets out to historicize the ever growing divide between the image and the reality of women in the United States. Refusing to fall for the trope of "post-feminism," Douglas is quick to point out that the current state of women's affairs is not reflective of the supposed successful completion of feminism, but is rather an indication of the insidious development of a cultural practice coined as "enlightened sexism." Defined as "feminist in its outward appearance . but sexist in its intent," enlightened sexism takes shape through carefully crafted representations of women that are "dedicated to the undoing of feminism" (p. 10). Douglas’ refusal of the conceptualization of this phenomenon as "post-feminism" stems from an astute observation that the current miserable state of women's affairs in the United States is not to be blamed on feminism (as the peddlers of enlightened sexism would have you think), but on "good, old-fashioned, grade-A sexism that reinforces good, old-fashioned, grade-A patriarchy" (p. 10). Aside from tracing the genealogy of enlightened sexism, this book emphasizes the sociopolitical consequences that are concealed beneath such a mentality, such as the systematic disenfranchisement of poor women and women of color under the so-called liberatory system of consumer capitalism, all while contradictory representations of women are disseminated as "proof" that the liberation of women has been achieved. -

Exploring “Girl Power”: Gender, Literacy and the Textual Practices of Young Women Attending an Elite School

English Teaching: Practice and Critique September, 2007, Volume 6, Number 2 http://education.waikato.ac.nz/research/files/etpc/2007v6n2art5 pp. 72-88 Exploring “girl power”: Gender, literacy and the textual practices of young women attending an elite school CLAIRE CHARLES Faculty of Education, Monash University ABSTRACT: Popular discourses concerning the relationship between gender and academic literacies have suggested that boys are lacking in particular, school-based literacy competencies compared with girls. Such discourses construct “gender” according to a binary framework and they obscure the way in which literacy and textual practices operate as a site in which gendered identities are constituted and negotiated by young people in multiple sites including schooling, which academic inquiry has often emphasized. In this paper I consider the school-based textual practices of young women attending an elite school, in order to explore how these practices construct “femininities”. Feminist education researchers have shown how young women negotiate discourses of feminine passivity and heterosexuality through their reading and writing practices. Yet discourses of girlhood and femininity have undergone important transformations in times of ‘girl power’ in which young women are increasingly constructed as successful, autonomous and sexually agentic. Thus young women’s reading and writing practices may well operate as a space in which new discourses around girlhood and femininity are constituted. Throughout the paper, I utilize the notion of “performativity”, understood through the work of Judith Butler, to show how textual practices variously inscribe and negotiate discourses of gender. Thus the importance of textual work in inscribing and challenging notions of gender is asserted. -

Cashing in on “Girl Power”: the Commodification of Postfeminist Ideals in Advertising

CASHING IN ON “GIRL POWER”: THE COMMODIFICATION OF POSTFEMINIST IDEALS IN ADVERTISING _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by MARY JANE ROGERS Dr. Cristina Mislán, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright by Mary Jane Allison Rogers 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled CASHING IN ON “GIRL POWER”: THE COMMODIFICATION OF POSTFEMINIST IDEALS IN ADVERTISING presented by Mary Jane Rogers, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cristina Mislán Professor Cynthia Frisby Professor Amanda Hinnant Professor Mary Jo Neitz CASHING IN ON “GIRL POWER” ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost gratitude goes to my advisor, Dr. Cristina Mislán, for supporting me throughout this process. She honed my interest in critically studying gender issues in the media, and her guidance, honesty and encouragement are the reasons I was able to develop the conclusions presented in this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Amanda Hinnant, Dr. Cynthia Frisby, and Dr. Mary Jo Neitz for their immensely helpful suggestions before and during the research process of this study. Their enthusiasm and guidance was incredibly meaningful, especially during the developmental stages of my research. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends and family for their ongoing support. Special mention needs to be made of Mallory, my cheerleader and motivator from the first day of graduate school, and my Dad and Mom, who have been there since the beginning. -

University Edition

UNIVERSITY EDITION CREATING AN EFFECTIVE CAMPAIGN TRAINER’S MODULE (UNIVERSITY EDITION) A ready-made workshop guide to teach others how to Development (C4D) framework as a guide. Prepared by (c/o Onyx Charity Association of Selangor) 1 ABOUT PROJECT LIBER8 Project Liber8 is a nonprofit organisation that aims to shift attitudes and behaviour toward the issue of human trafficking and exploitation through youth mobilisation, public education, technology, research and creating strong partnerships. Our mission for this project is based on the Triple-A concept; Attention, Attachment, and Action. We aim to attract the ATTENTION of citizens to the issue of human trafficking, as it is only with proper education that people are truly aware of the situation. We work towards gaining the ATTACHMENT of the public with regards to this issue so that we, as one movement can ACT together to bring change in a more effective and efficient manner. ABOUT ADVOC8 ON THE ROAD (UNIVERSITY EDITION) Advoc8 On The Road (University Edition) is a campaign designed to be a strong platform for youths to understand and learn about women migrant workers’ contributions to promote behavioural change among young Malaysians. This activity/conference/meeting is supported by the Spotlight Initiative, a global, multi-year partnership between the European Union and the United Nations to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls. This second component of this initiative is a module on creating impactful campaigns. At the end of this workshop, youths should be able to : • Research, identify and comprehend relevant issues. • Apply critical thinking to develop solutions unique to the needs and resources of their community. -

Skyline Orchestras

PRESENTS… SKYLINE Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Skyline, led by Ross Kash. Skyline has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 10 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Skyline Members: • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES…………………………..…….…ROSS KASH • VOCALS……..……………………….……………………………….….BRIDGET SCHLEIER • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..………….…………………….……VINCENT FONTANETTA • GUITAR………………………………….………………………………..…….JOHN HERRITT • SAXOPHONE AND FLUTE……………………..…………..………………DAN GIACOMINI • DRUMS, PERCUSSION AND VOCALS……………………………….…JOEY ANDERSON • BASS GUITAR, VOCALS AND UKULELE………………….……….………TOM MCGUIRE • TRUMPET…….………………………………………………………LEE SCHAARSCHMIDT • TROMBONE……………………………………………………………………..TIM CASSERA • ALTO SAX AND CLARINET………………………………………..ANTHONY POMPPNION www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 DANCE: 24K — BRUNO MARS A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY — FERGIE A SKY FULL OF STARS — COLD PLAY LONELY BOY — BLACK KEYS AIN’T IT FUN — PARAMORE LOVE AND MEMORIES — O.A.R. ALL ABOUT THAT BASS — MEGHAN TRAINOR LOVE ON TOP — BEYONCE BAD ROMANCE — LADY GAGA MANGO TREE — ZAC BROWN BAND BANG BANG — JESSIE J, ARIANA GRANDE & NIKKI MARRY YOU — BRUNO MARS MINAJ MOVES LIKE JAGGER — MAROON 5 BE MY FOREVER — CHRISTINA PERRI FT. ED SHEERAN MR. SAXOBEAT — ALEXANDRA STAN BEST DAY OF MY LIFE — AMERICAN AUTHORS NO EXCUSES — MEGHAN TRAINOR BETTER PLACE — RACHEL PLATTEN NOTHING HOLDING ME BACK — SHAWN MENDES BLOW — KE$HA ON THE FLOOR — J. -

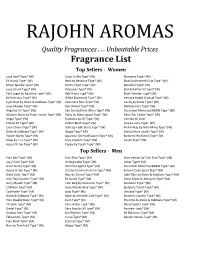

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type*