No. 250 Cabrini Boulevard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

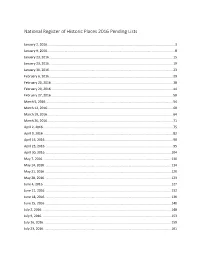

National Register of Historic Places Pending Lists for 2016

National Register of Historic Places 2016 Pending Lists January 2, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 9, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 8 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 January 30, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 23 February 6, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 29 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 38 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 44 February 27, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 50 March 5, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................... -

RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (Aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5t11 Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 29, 2002, Designation List 340 LP-2118 RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5T11 Street), Manhattan. Built 1925-27; Emery Roth, architect, with Thomas Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1312, Lot 70. On July 16, 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ritz Tower, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Ross Moscowitz, representing the owners of the cooperative spoke in opposition to designation. At the time of designation, he took no position. Mark Levine, from the Jamestown Group, representing the owners of the commercial space, took no position on designation at the public hearing. Bill Higgins represented these owners at the time of designation and spoke in favor. Three witnesses testified in favor of designation, including representatives of State Senator Liz Kruger, the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission has received letters in support of designation from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, from Community Board Five, and from architectural hi storian, John Kriskiewicz. There was also one letter from a building resident opposed to designation. Summary The Ritz Tower Apartment Hotel was constructed in 1925 at the premier crossroads of New York's Upper East Side, the comer of 57t11 Street and Park A venue, where the exclusive shops and artistic enterprises of 57t11 Street met apartment buildings of ever-increasing height and luxury on Park Avenue. -

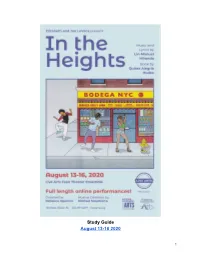

Study Guide August 13-16 2020

Study Guide August 13-16 2020 1 Dramaturg’s Note by Shannon Montague I am an educator. My entire life has been focused on the premise that curiosity is a gift with never-ending benefits. The more we seek to understand, the better. When I set out to create a packet of key terms for the cast of In the Heights, I didn’t think it would become the show’s official Study Guide, and that I would become the show’s dramaturg. I simply wanted to illuminate the world that Lin-Manuel Miranda created, complete with characters who are multi-layered and a world that spans generations. I not only sought to share what I knew, but also, more importantly, to understand what I didn’t know. I lived in the same time as Big Pun. I made mixtapes. Our cast did not. Miranda understands Latinx culture and growing up in New York City. I do not. What we all understand is that musical theater and the arts have power. That’s why we are here. I simply sought to fill the gaps. There are moments in this show that resonate across generations. The character Sonny in his solo rap during the song “96,000” says: “What about immigration?/ Politicians be hatin’./ Racism in this nation’s gone from latent to blatant./ I’ll cash my ticket and picket, invest in protest,/ never lost my focus till the city takes notice/ and you know this man! I’ll never sleep/ because the ghetto has a million promises/ for me to keep!” Whether you were alive in 1999 when Miranda was writing his earliest draft of the show or in 1943 when Abuela Claudia arrived in New York or you just know today, seven years since #BlackLivesMatter was founded, what we all see is the continued struggle for BIPOC to be seen, heard and known in America. -

Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report

Cover Photograph: Court Street looking south along Skyscraper Row towards Brooklyn City Hall, now Brooklyn Borough Hall (1845-48, Gamaliel King) and the Brooklyn Municipal Building (1923-26, McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin). Christopher D. Brazee, 2011 Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report Prepared by Christopher D. Brazee Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Technical Assistance by Lauren Miller Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Pablo E. Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Michael Devonshire Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP ................... FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 1 BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ............................. 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT ........................................................................................ 5 Early History and Development of Brooklyn‟s Civic Center ................................................... 5 Mid 19th Century Development -

2018 AIA Fellowship

This cover section is produced by the AIA Archives to show information from the online submission form. It is not part of the pdf submission upload. 2018 AIA Fellowship Nominee Pamela Jerome Organization Architectural Preservation Studio, DPC Location New York, NY Chapter AIA New York State; AIA New York Chapter Category of Nomination Category One - Preservation Summary Statement Pamela Jerome is an innovative leader in application of theory and doctrine on the preservation of significant structures in the US and worldwide. Her award-winning projects, volunteer work , publications, and training have international impact. Education M Sc Historic Preservation, Columbia University, New York, NY, 1989-1991 ; B Arch, Architectural Engineering, National Technical University, Athens, Greece, 1974-1979 Licensed in: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Greece Employment Architectural Preservation Studio, DPC, 2015-present (2.5 years); Wank Adams Slavin Associate LLP (WASA), 1986-2015 (29 years); Consulting for Architect, 1984-1986 (2 years); Stinchomb and Monroe, 1982-1984 (2 years); WYS Design, 1981-1982 (1 year) October 5, 2017 Karen Nichols, FAIA, Chair, 2018 Jury of Fellows The American Institute of Architects, 1735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20006-5292 Re: Pamela Jerome, AIA – Sponsorship for Elevation to Fellowship Dear Ms. Nichols: As a preservation and sustainability architect, the Past President of the Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) and the President of the Buffalo Architecture Center, it is my privilege to sponsor Pamela Jerome, the President of Architectural Preservation Studio, for nomination as a Fellow in the American Institute of Architects. Pamela and I are both graduates of the Master of Science in Historic Preservation program at Columbia University. -

Document.Pdf

Besen & Associates Investment Sales Team Hilly Soleiman Director (646) 424-5078 [email protected] Ronald H. Cohen Chief Sales Officer (212) 424-5317 [email protected] Paul J. Nigido Senior Financial Analyst (646) 424-5350 [email protected] Jared Rehberg Marketing Manager (646) 424-5067 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Investment Highlights Property Overview 9 Location Map Property Photos Financial Overview 13 Income/Expense Report Commercial Rent Roll Property Diligence 26 Certificate of Occupancy Location Overview 28 Transportation Maps Zoning Overview 31 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Besen & Associates, Inc., as exclusive agent for ownership, is pleased to offer for sale 4468-4474 Broadway, New York, NY 10040 (the “Property”), an elevatored, 2-story commercial building consisting of 6 stores and 5 offices. Built in 1991, the Property contains 20,000± SF and features 100’ of prime retail frontage along Broadway. 4468-4474 Broadway is situated on the east side of Broadway between Fairview Avenue and 192nd Street and is 4468-4474 Broadway located in one of the most desirable sections of Washington Heights in Northern Manhattan, boasting high foot traffic and bustling retail. The stores are currently renting at well-below market rates, offering tremendous upside to new ownership, and the Property contains 14,400± SF of unused air rights (TDR’s) for future redevelopment or value-add potential. The Property is located just north of the George Washington Bridge between Fort Tyron Park and Harlem River Park. Commuters are well served by public transportation, including the 190th Street subway station [“A”] and the 191st Street subway station [“1”]. -

Manhattan Borough President's Office FY 2020 Schools Capital Grant Awards- Sorted by Community Board

Manhattan Borough President's Office FY 2020 Schools Capital Grant Awards- Sorted by Community Board School Name School Number Project Title Project Address CB CD FY 20 Award 55 Battery Place Battery Park City School 02M276 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10280 Lower Manhattan Arts 350 Grand Street 02M308 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 Academy New York, NY 10002 75 Broad Street Millennium High School 02M418 Classroom Projectors 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10004 201 Warren Street Public School 89 02M089 Technology Upgrade Room 208 1 1 $80,000 New York, NY 10282 55 Battery Place Public School 94 75M094 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10280 Richard R. Green High 7 Beaver Street 02M580 Technology Upgrade 1 1 $75,000 School of Teaching New York, NY 10004 345 Chambers Street Stuyvesant High School 02M475 Theater Lights 1 1 $75,000 New York, NY 10282 University Neighborhood 200 Monroe Street 01M448 Bathroom Upgrade 1 1 $50,000 High School New York, NY 10002 10 South St Urban Assembly New 02M551 Electrical Upgrade Slip 7 1 1 $52,000 York Harbor School New York, NY 10004 131 Avenue of the Americas Chelsea CTE 02M615 Technology Upgrade New York, NY 10013 2 3 $100,000 High School 16 Clarkson Street City-As-School 02M560 Technology Upgrade 2 3 $75,000 New York, NY 10014 2 Astor Place Harvey Milk High School 02M586 Technology Upgrade 3rd Floor 2 2 $100,000 New York, NY 10003 High School of Hospitality 525 West 50th Street 02M296 Technology Upgrade 2 3 $75,000 Management New York, NY 10019 75 Morton Street Middle School 297 02M297 Hydroponics Lab 2 3 $50,000 New York, NY 10014 411 Pearl Street Murray Bergtraum 02M282 Water Fountains Room 436 2 1 $150,000 Campus New York, NY 10038 NYC Lab School for 333 West 17th Street 02M412 Technology Upgrade 2 3 $150,000 Collaborative Studies New York, NY 10011 P.S. -

Page Numbers in Italics Refer to Illustrations. Abenad

INDEX Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations. Abenad Corporation, 42 Ballard, William F. R., 247, 252, 270 Abrams, Charles, 191 Barnes, Edward Larabee, 139, 144 Acker, Ed, 359 Barnett, Jonathan, 277 Action Group for Better Architecture in New Bauen + Wohnen, 266 York (AGBANY), 326–327 Beaux-Arts architecture, xiv, 35, 76, 255, 256, Airline industry, xiv, 22, 26, 32, 128, 311, 314, 289, 331, 333, 339, 344, 371. See also 346, 357–360, 361–362, 386 Grand Central Terminal Albers, Josef, 142–143, 153, 228, 296, 354, Belle, John (Beyer Blinder Belle Architects), 407n156 354 American Institute of Architects (AIA), 3, 35, Belluschi, Pietro, 70–77, 71, 80, 223, 237, 328 75, 262, 282, 337 AIA Gold Medal, 277, 281 Conference on Ugliness, 178–179 and the Architectural Record, 188, 190, 233, New York Chapter, 2, 157 235, 277 American Institute of Planners, 157 and art work, Pan Am Building, 141–144 Andrews, Wayne, 175–176, 248, 370 as co-designer of the Pan Am Building, xiii, 2, “Anti-Uglies,” 177, 327 50, 59, 77, 84, 87, 117, 156–157, 159, 160– “Apollo in the democracy” (concept), 67–69, 163, 165, 173, 212, 248, 269, 275, 304, 353, 159. See also Gropius, Walter 376 (see also Gropius/Belluschi/Roth collab- Apollo in the Democracy (book), 294–295. See oration) also Gropius, Walter on collaboration of art and architecture, 142– Collins review of, 294–295 143 Architectural criticism, xiv, xvi, 53, 56, 58, 227, collaboration with Gropius, 72, 75, 104, 282, 232, 257, 384–385, 396n85. See also 397n119 Huxtable, Ada Louise contract with Wolfson, 60–61, -

Primary Contest List For

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2014 - 09/09/2014 Printed On: 8/19/2014 2:57:53PM BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2014 - 09/09/2014 8/19/2014 2:57:53PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Democratic Party Nominations for the following offices and positions: Governor Lieutenant Governor State Senator Member of the Assembly Male State Committee Female State Committee Delegate to Judicial Convention Alternate Delegate to the Judicial Convention Page 2 of 10 BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2014 - 09/09/2014 8/19/2014 2:57:53PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Governor - Citywide Zephyr R. Teachout 171 Washington Park 5 Brooklyn, NY 11205 Andrew M. Cuomo 4 Bittersweet Lane Mount Kisco, NY 10549 Randy A. Credico 311 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10023 Lieutenant Governor - Citywide Kathy C. Hochul 405 Gull Landing Buffalo, NY 14202 Timothy Wu 420 West 25 Street 7G New York, NY 10001 State Senator - 28th Senatorial District Shota N. Baghaturia 1691 2 Avenue 4S New York, NY 10128 Liz Krueger 350 East 78 Street 5G New York, NY 10075 State Senator - 31st Senatorial District Adriano Espaillat 62 Park Terrace West A87 New York, NY 10034 Luis Tejada 157-10 Riverside Drive West 5N New York, NY 10032 Robert Jackson 499 Fort Washington Avenue New York, NY 10033 Member of the Assembly - 71st Assembly District Kelley S. Boyd 240 Cabrini Boulevard New York, NY 10033 Herman D. -

Download the 2019 Map & Guide

ARCHITECTURAL AND CULTURAL Map &Guide FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts Architectural and Cultural Map and Guide Founded in 1982, FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts is an independent, not-for-profit membership organization dedicated to preserving the architectural legacy, livability, and sense of place of the Upper East Side by monitoring and protecting its seven Historic Districts, 131 Individual Landmarks, and myriad significant buildings. Walk with FRIENDS as we tour some of the cultural and architectural sites that make the Upper East Side such a distinctive place. From elegant apartment houses and mansions to more modest brownstones and early 20th-century immigrant communities, the Upper East Side boasts a rich history and a wonderfully varied built legacy. With this guide in hand, immerse yourself in the history and architecture of this special corner of New York City. We hope you become just as enchanted by it as we are. FRIENDS’ illustrated Architectural and Cultural Map and Guide includes a full listing of all of the Upper East Side’s 131 Individual Landmarks. You can find the location of these architectural gems by going to the map on pages 2-3 of the guide and referring to the numbered green squares. In the second section of the guide, we will take you through the history and development of the Upper East Side’s seven Historic Districts, and the not landmarked, though culturally and architecturally significant neighborhood of Yorkville. FRIENDS has selected representative sites that we feel exemplify each district’s unique history and character. Each of the districts has its own color-coded map with easy-to-read points that can be used to find your own favorite site, or as a self-guided walking tour the next time you find yourself out strolling on the Upper East Side. -

The Benjamin in Honor of the Family-Owned Company’S Founder, Benjamin Denihan, Sr

FACT SHEET ADDRESS: 125 East 50th Street at Lexington Avenue New York, NY 10022 PHONE: For reservations call: 1-888-4-BENJAMIN Hotel tel: 212-715-2500 Hotel fax: 212-715-2525 WEB SITE: thebenjamin.com GENERAL MANAGER: Steve Sasso OVERVIEW: Situated in an ideal midtown Manhattan locale, The Benjamin is a 209-room beaux-arts boutique hotel that exudes the ambiance of a private club. Newly redesigned accommodations by Rottet Studio range from guestrooms with kitchenettes to one-bedroom terrace suites with inspiring skyline views. Noted as “one of the 50 favorite restaurants” by The New York Times, The National by internationally acclaimed Iron Chef Geoffrey Zakarian is housed on the first floor and showcases modern bistro cuisine in a chic grand cafe or in-room dining. Known for coiffing the tresses of celebs, stylist Federico Calce presents Federico Hair & Spa at The Benjamin. Guests have access to blowouts, color, cuts, manicures and massages in- salon or in-room. The Benjamin understands its guests tend to be leaders, owing their accomplishments to a strong work ethic and a busy lifestyle. Through our programs, amenities and services, we aim to foster productivity and wellbeing, offering services for restful sleep, nourishment, exercise, personal care, and inspiration—five tenets integral to success. HISTORY: Originally established in 1927 as the former Hotel Beverly, the hotel is considered to be one of the most successful creations by famed architect Emery Roth. The edifice so inspired artist Georgia O’Keeffe that she painted it as the subject of her piece “New York—Night.” In November 1997, members of the Denihan family purchased the hotel and renamed it The Benjamin in honor of the family-owned company’s founder, Benjamin Denihan, Sr. -

Landmarks Commission Report

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 29, 2002, Designation List 340 LP-2118 RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (aka 461- 465 Park Avenue, and 101 East 57th Street), Manhattan. Built 1925-27; Emery Roth, architect, with Thomas Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1312, Lot 70. On July 16, 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ritz Tower, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Ross Moscowitz, representing the owners of the cooperative spoke in opposition to designation. At the time of designation, he took no position. Mark Levine, from the Jamestown Group, representing the owners of the commercial space, took no position on designation at the public hearing. Bill Higgins represented these owners at the time of designation and spoke in favor. Three witnesses testified in favor of designation, including representatives of State Senator Liz Kruger, the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission has received letters in support of designation from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, from Community Board Five, and from architectural historian, John Kriskiewicz. There was also one letter from a building resident opposed to designation. Summary The Ritz Tower Apartment Hotel was constructed in 1925 at the premier crossroads of New York’s Upper East Side, the corner of 57th Street and Park Avenue, where the exclusive shops and artistic enterprises of 57th Street met apartment buildings of ever-increasing height and luxury on Park Avenue.