The Social Psychology of Stress, Health, and Coping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

The History and Philosophy of Health Psychology And

Revista Psicologia e Saúde. DOI: hƩ p://dx.doi.org/10.20435/pssa.v10i2.693 25 Mind the Gap: The History and Philosophy of Health Psychology and Mindfulness Atenção aos Detalhes: A História e Filosofi a da Psicologia da Saúde e Mindfulness Ojo a los Detalles: Historia y Filosoİ a de la Psicología de la Salud y Mindfulness Shayna Fox Lee1 York University, Canada Jacy L. Young Abstract The recent surge in popularity of the concept ‘mindfulness’ in academic, professional, and popular psychology has been remarkable. The ease with which mindfulness has gained trac on in the health sciences and cultural imagina on makes it apparent mindfulness is well-suited to our current social climate, appealing to both, experts and laypeople. As a subdiscipline established rela vely late in the twen eth century, health psychology has a unique rela onship to mindfulness. This ar cle elucidates the shared roots between health psychology and mindfulness as a psychological construct and fi eld of research, providing a frame of reference for the ways in which health psychology and mindfulness share similar theore cal and methodological challenges that aff ect their integra on into health, social systems, and services. Keywords: mindfulness, history, philosophy Resumo O recente aumento na popularidade do conceito mindfulness (plena atenção) tem sido notado signifi ca vamente na área acadêmica e professional da psicologia. O termo tem se fortalecido nas ciências da saúde, além do imaginário cultural para expressar um contexto contemporâneo da sociedade, atraindo tanto especialistas quanto leigos. Sendo uma sub-área estabelecida rela vamente tardia no fi nal do século XX, a psicologia da saúde tem uma relação singular com o conceito. -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

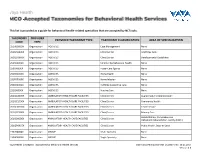

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

Social Exclusion in Schizophrenia Psychological and Cognitive

Journal of Psychiatric Research 114 (2019) 120–125 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Psychiatric Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpsychires Social exclusion in schizophrenia: Psychological and cognitive consequences T ∗ L. Felice Reddya,b, , Michael R. Irwinc, Elizabeth C. Breenc, Eric A. Reavisb,a, Michael F. Greena,b a Department of Veterans Affairs VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), Greater Los Angeles VA Healthcare System 11301 Wilshire Blvd, Building 210, Los Angeles, CA, 90073, USA b UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience & Human Behavior, David Geffen School of Medicine, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA, 90024, USA cCousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, Semel Institute for Neuroscience, UCLA, 300 Medical Plaza Driveway, Los Angeles, CA, 90024, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Social exclusion is associated with reduced self-esteem and cognitive impairments in healthy samples. Schizophrenia Individuals with schizophrenia experience social exclusion at a higher rate than the general population, but the Cyberball specific psychological and cognitive consequences for this group are unknown. We manipulated social exclusion Social exclusion in 35 participants with schizophrenia and 34 demographically-matched healthy controls using Cyberball, a Cognition virtual ball-tossing game in which participants believed that they were either being included or excluded by peers. All participants completed both versions of the task (inclusion, exclusion) on separate visits, as well as measures of psychological need security, working memory, and social cognition. Following social exclusion, individuals with schizophrenia showed decreased psychological need security and working memory. Contrary to expectations, they showed an improved ability to detect lies on the social cognitive task. -

Social Neuroscience and Psychopathology: Identifying the Relationship Between Neural Function, Social Cognition, and Social Beha

Hooker, C.I. (2014). Social Neuroscience and Psychopathology, Chapter to appear in Social Neuroscience: Mind, Brain, and Society Social Neuroscience and Psychopathology: Identifying the relationship between neural function, social cognition, and social behavior Christine I. Hooker, Ph.D. ***************************** Learning Goals: 1. Identify main categories of social and emotional processing and primary neural regions supporting each process. 2. Identify main methodological challenges of research on the neural basis of social behavior in psychopathology and strategies for addressing these challenges. 3. Identify how research in the three social processes discussed in detail – social learning, self-regulation, and theory of mind – inform our understanding of psychopathology. Summary Points: 1. Several psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism, are characterized by social functioning deficits, but there are few interventions that effectively address social problems. 2. Treatment development is hindered by research challenges that limit knowledge about the neural systems that support social behavior, how those neural systems and associated social behaviors are compromised in psychopathology, and how the social environment influences neural function, social behavior, and symptoms of psychopathology. 3. These research challenges can be addressed by tailoring experimental design to optimize sensitivity of both neural and social measures as well as reduce confounds associated with psychopathology. 4. Investigations on the neural mechanisms of social learning, self-regulation, and Theory of Mind provide examples of methodological approaches that can inform our understanding of psychopathology. 5. High-levels of neuroticism, which is a vulnerability for anxiety disorders, is related to hypersensitivity of the amygdala during social fear learning. 6. High-levels of social anhedonia, which is a vulnerability for schizophrenia- spectrum disorders, is related to reduced lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) activity 1 Hooker, C.I. -

When Psychometrics Meets Epidemiology and the Studies V1.Pdf

When psychometrics meets epidemiology, and the studies which result! Tom Booth [email protected] Lecturer in Quantitative Research Methods, Department of Psychology, University of Edinburgh Who am I? • MSc and PhD in Organisational Psychology – ESRC AQM Scholarship • Manchester Business School, University of Manchester • Topic: Personality psychometrics • Post-doctoral Researcher • Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, Department of Psychology, University of Edinburgh. • Primary Research Topic: Cognitive ageing, brain imaging. • Lecturer Quantitative Research Methods • Department of Psychology, University of Edinburgh • Primary Research Topics: Individual differences and health; cognitive ability and brain imaging; Psychometric methods and assessment. Journey of a talk…. • Psychometrics: • Performance of likert-type response scales for personality data. • Murray, Booth & Molenaar (2015) • Epidemiology: • Allostatic load • Measurement: Booth, Starr & Deary (2013); (Unpublished) • Applications: Early life adversity (Unpublished) • Further applications Journey of a talk…. • Methodological interlude: • The issue of optimal time scales. • Individual differences and health: • Personality and Physical Health (review: Murray & Booth, 2015) • Personality, health behaviours and brain integrity (Booth, Mottus et al., 2014) • Looking forward Psychometrics My spiritual home… Middle response options Strongly Agree Agree Neither Agree nor Disagree Strong Disagree Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 Strongly Agree Agree Unsure Disagree Strong Disagree -

Health Psychology 19

PSY_C19.qxd 1/2/05 3:52 pm Page 408 Health Psychology 19 CHAPTER OUTLINE LEARNING OBJECTIVES INTRODUCTION HEALTH BELIEFS AND BEHAVIOURS Behaviour and mortality The role of health beliefs Integrated models ILLNESS BELIEFS The dimensions of illness beliefs A model of illness behaviour Health professionals’ beliefs THE STRESS–ILLNESS LINK Stress models Does stress cause illness? CHRONIC ILLNESS Profile of an illness Psychology’s role FINAL THOUGHTS SUMMARY REVISION QUESTIONS FURTHER READING PSY_C19.qxd 1/2/05 3:52 pm Page 409 Learning Objectives By the end of this chapter you should appreciate that: n health psychologists study the role of psychology in health and wellbeing; n they examine health beliefs as possible predictors of health-related behaviours; n health psychology also examines beliefs about illness and how people conceptualize their illness; n a health professional’s beliefs about the symptoms, the illness or the patient can have important implications; n stress is the product of the interaction between the person and their environment – it can influence illness and the stress–illness link is influenced by coping and social support; n beliefs and behaviours can influence whether a person becomes ill in the first place, whether they seek help and how they adjust to their illness. INTRODUCTION Health psychology is a relatively recent yet fast- reflects the biopsychosocial model of health and growing sub-discipline of psychology. It is best illness that was developed by Engel (1977, understood by answering the following questions: 1980). Because, in this model, illness biopsychosocial the type of inter- n What causes illness and who is responsible is regarded as the action between biological factors (e.g. -

PSY 324: Social Psychology of Emotion

Advanced Social Psychology: Emotion PSY 324 Section A Spring 2008 Instructor: Christina M. Brown, M.A., A.B.D. CRN: 66773 E-mail: [email protected] Class Time: Monday, Wednesday, Friday Office Hours: 336 Psych MW 2:00-3:00 or by appt 1:00 - 1:50 pm Office Phone: (513) 529-1755 Location: 127 PSYC Required Readings Niedenthal, P. M., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2006). Psychology of emotion: Interpersonal, experiential, and cognitive approaches. New York: Taylor & Francis. *The textbook is $35 Amazon.com and can be found on Half.com for as cheap as $26. Journal articles will be assigned regularly throughout the semester. These will be available as downloadable .pdf files on Blackboard. Course Description This course is on the advanced social psychology of emotion. Students will gain an understanding of the function of emotion, structure of emotion, and the interplay between emotion, cognition, behavior, and physiology. We will spend most of our time discussing theories of emotion and empirical evidence supporting and refuting these theories. Research is the foundation of psychology, and so a considerable amount of time will be spent reading, discussing, and analyzing research. There will be regular discussions that will each focus on a single assigned reading (always a journal article, which will be made available on Blackboard), and it is my hope that these discussions are active, thoughtful, and generative (meaning that students leave the discussion with research questions and ideas for future research). Although there will be some days entirely devoted to discussion, I hope that we can weave discussion into lecture-based days as well. -

Clinical Health Psychology Fellowship

Clinical Health Psychology Fellowship APA-ACCREDITED CLINICAL HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY FELLOWSHIP AT THE MAYO CLINIC APA-Accredited Clinical Health Psychology Fellowship at the Mayo Clinic The Clinical Health Psychology Fellowship is one of three tracks offered in the Medical Psychology Post-Doctoral Fellowship at Mayo Clinic. This APA-Accredited Fellowship is the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, which is one of the largest psychiatric treatment groups in the United States, with more than 80 psychologists and psychiatrists. The two-year fellowship includes clinical activities, 30% protected time for research, educational activities, as well as opportunities for teaching/leadership. The Clinical Health Psychology Fellowship offers both breadth and depth in health psychology training. Fellows choose a specialty area (“major rotation”) in which they focus the majority of their clinical and research work. Fellows receive their clinical supervision and research mentorship in their specialty area. In addition, fellows can obtain broad training through several minor rotations. The rotational schedule is flexible based on the fellows’ interests and goals. All major rotation areas are also offered as minor rotations. “Fellows are able to complete minor rotations in each specialty area during the two-year fellowship, or they may choose to focus on their major area of concentration.” Many of our faculty hold leadership positions in the department and the institution, offering our fellows formal and informal professional development opportunities to learn about the role of the Clinical Health Psychologist within an academic medical center setting. Our faculty includes individuals from diverse cultural and clinical training backgrounds. We strongly encourage diverse applicants to apply to our program, including international applicants.