1.1. Circuit-Bending and DIY Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Videogame Music: Chiptunes Byte Back?

Videogame Music: chiptunes byte back? Grethe Mitchell Andrew Clarke University of East London Unaffiliated Researcher and Institute of Education 78 West Kensington Court, University of East London, Docklands Campus Edith Villas, 4-6 University Way, London E16 2RD London W14 9AB [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Musicians and sonic artists who use videogames as their This paper will explore the sonic subcultures of videogame medium or raw material have, however, received art and videogame-related fan art. It will look at the work of comparatively little interest. This mirrors the situation in art videogame musicians – not those producing the music for as a whole where sonic artists are similarly neglected and commercial games – but artists and hobbyists who produce the emphasis is likewise on the visual art/artists.1 music by hacking and reprogramming videogame hardware, or by sampling in-game sound effects and music for use in It was curious to us that most (if not all) of the writing their own compositions. It will discuss the motivations and about videogame art had ignored videogame music - methodologies behind some of this work. It will explore the especially given the overlap between the two communities tools that are used and the communities that have grown up of artists and the parallels between them. For example, two around these tools. It will also examine differences between of the major videogame artists – Tobias Bernstrup and Cory the videogame music community and those which exist Archangel – have both produced music in addition to their around other videogame-related practices such as modding gallery-oriented work, but this area of their activity has or machinima. -

The Hell Harp of Hieronymus Bosch. the Building of an Experimental Musical Instrument, and a Critical Account of an Experience of a Community of Musicians

1 (114) Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music, with specialization in Improvisation Performance Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring 2019 Author: Johannes Bergmark Title: The Hell Harp of Hieronymus Bosch. The building of an experimental musical instrument, and a critical account of an experience of a community of musicians. Supervisors: Professor Anders Jormin, Professor Per Anders Nilsson Examiner: Senior Lecturer Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT Taking a detail from Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden Of Earthly Delights as a point of departure, an instrument is built for a musical performance act deeply involving the body of the musician. The process from idea to performance is recorded and described as a compositional and improvisational process. Experimental musical instrument (EMI) building is discussed from its mythological and sociological significance, and from autoethnographical case studies of processes of invention. The writer’s experience of 30 years in the free improvisation and new music community, and some basic concepts: EMIs, EMI maker, musician, composition, improvisation, music and instrument, are analyzed and criticized, in the community as well as in the writer’s own work. The writings of Christopher Small and surrealist ideas are main inspirations for the methods applied. Keywords: Experimental musical instruments, improvised music, Hieronymus Bosch, musical performance art, music sociology, surrealism Front cover: Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly -

Studio Bench: the DIY Nomad and Noise Selector

Studio Bench: the DIY Nomad and Noise Selector Amit Dinesh Patel Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2019 Abstract This thesis asks questions about developing a holistic practice that could be termed ‘Studio Bench’ from what have been previously seen as three separate activities: DIY electronic instrument making, sound studio practice, and live electronics. These activities also take place in three very specific spaces. Firstly, the workshop with its workbench provides a way of making and exploring sound(- making) objects, and this workbench is considered more transient and expedient in relation to finding sounds, and the term DIY Nomad is used to describe this new practitioner. Secondly, the recording studio provides a way to carefully analyse sound(-making) objects that have been self-built and record music to play back in different contexts. Finally, live practice is used to bridge the gap between the workbench and studio, by offering another place for making and an opportunity to observe and listen to the sound(-making) object in another environment in front of a live audience. The DIY Nomad’s transient nature allows for free movement between these three spaces, finding sounds and making in a holistic fashion. Spaces are subverted. Instruments are built in the studio and recordings made on the workbench. From the nomadity of the musician, sounds are found and made quickly and intuitively, and it is through this recontextualisation that the DIY Nomad embraces appropriation, remixing, hacking and expediency. The DIY Nomad also appropriates cultures and the research is shaped through DJ practice - remixing and record selecting - noise music, and improvisation. -

H-France Review Vol. 19 (May 2019), No. 65 Jacques Amblard And

H-France Review Volume 19 (2019) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 19 (May 2019), No. 65 Jacques Amblard and Emmanuel Aymès, Micromusique et ludismes régressifs depuis 2000. Aix-en- Provence: Presses Universitaires de Provence, 2017. 124 pages. Illustrations, cartes. 7 € (broché). ISBN: 9791032001233. Review by Edward Campbell, University of Aberdeen. Micromusique et ludismes régressifs depuis 2000 by Jacques Amblard and Emmanuel Aymès is a slim volume at 124 pages, but nevertheless a fascinating exploration of a contemporary musical phenomenon. Setting out from the concept of “le redevenir-enfant,” a phrase with more than a hint of the Deleuzian about it (though the philosopher is not mentioned in the text), the book examines a tendency towards infantilisation which the authors trace to the 1830s but which has become much more evident in more recent times with the sociological identification of the “adulescent” in the 1970s and 1980s, certain developments in the plastic arts from the late 1980s, in certain strains of popular music that arose with the availability of personal computers in the late 1980s and 1990s, and finally in aspects of Western art music [“musique savante”] from the new millennium. What Amblard and Aymès term micromusic is also known as chiptune or 8-bits, the post-punk music of geeks and hackers with whom game technologies such as Game Boy are transformed into sources and instruments for music-making. While this, for the authors, is ostensibly regressive and nothing less than the “acme” of infantilisation, it signals at the same time, as the back cover notes, the “subtile inversion” of the player-musician into an anti-consumer within processes of alternative globalisation. -

Freely Improvised and Non-Academic Electroacoustic Music by Urban Folks

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.26 Freely improvised and non-academic electroacoustic music by urban folks Harold Schellinx Emmanuel Ferrand ana-R & IESA ana-R & Sorbonne Université Paris, France Paris, France [email protected] [email protected] We discuss history and characteristics of the evolving global networks of anarchic communities of independent experimental musical artists that over the past half century have continued to flourish outside of established cultural institutions and with but incidental, ad hoc, financial funding. As a case-study related to our own practice we give an in-depth look into the International Headphone Festival Le Placard (1998-2013), a series of ephemeral (headphones only) concert-sites and laboratories for (not only) sound art and electronic music, that was highly innovative and influential also in the worlds of academic and commercial music, though —being the result of collective creative efforts, transmitted in (contemporary equivalents of) the fundamentally aural tradition that is typical of artistic folk modes— this is an influence destined to remain anonymous, hence un- credited. Improvised electroacoustic music, folklore, DIY, circuit-bending, artist networks 1. INTRODUCTION: URBAN FOLKS ingeniously depicted the face of an oscilloscope tube, over which flowed an ever-changing dance Attempts at a rigorous and all-embracing definition of Lissajous figures. [...] A sudden chorus of of TKOMTIUH (an acronym that, with a hat tip to whoops and yibbles burst from a kind of juke box TAFKAP, makes a wink at mid-1990s pop music at the far end of the room. Everybody quit talking. history, standing as it does for 'The Kind Of Music [...] "What's happening?" Oedipa whispered. -

A Geology of Media

A GEOLOGY OF MEDIA JUSSI PARIKKA Electronic Mediations, Volume 46 University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis • London Parikka.indd 3 28/01/2015 12:46:14 PM A version of chapter 2 was published as The Anthrobscene (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). Portions of chapter 4 appeared in “Dust and Exhaustion: The Labor of Media Materialism,” CTheory, October 2, 2013, http://www.ctheory.net. The Appendix was previously published as “Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeol- ogy into an Art Method,” Leonardo 45, no. 5 (2012): 424–30 . Portions of the book appeared in “Introduction: The Materiality of Media and Waste,” in Medianatures: The Materiality of Information Technology and Electronic Waste, ed. Jussi Parikka (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Open Humanities Press, 2011), and in “Media Zoology and Waste Management: Animal Energies and Medianatures,” NECSUS European Journal of Media Studies, no. 4 (2013): 527– 44. Copyright 2015 by Jussi Parikka All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Parikka, Jussi. A geology of media / Jussi Parikka. (Electronic mediations ; volume 46) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-9551-5 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8166-9552-2 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Mass media. 2. Mass media—Social aspects. 3. -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by Paxton Christopher Haven 2020 The Thesis Committee for Paxton Christopher Haven Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: Oops…They Did It Again: Pop Music Nostalgia, Collective (Re)memory, and Post-Teeny Queer Music Scenes APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Suzanne Scott, Supervisor Curran Nault Oops…They Did It Again: Pop Music Nostalgia, Collective (Re)memory, and Post-Teeny Queer Music Scenes by Paxton Christopher Haven Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To my parents, Chris and Fawn, whose unwavering support has instilled within me the confidence, kindness, and sense of humor to tackle anything my past, present, and future may hold. Acknowledgements Thank you to Suzanne Scott for providing an invaluable amount of time and guidance helping to make sense of my longwinded rants and prose. Our conversations throughout the brainstorming and writing process, in addition to your unwavering investment in my scholarship, made this project possible. Thank you to Curran Nault for illustrating to me the infinite potentials within merging the academic and the personal. Watching you lead the classroom with empathy and immense consideration for the lives, legacies, and imaginations of queer and trans artists/philosophers/activists has made me a better scholar and person. Thank you to Taylor for enduring countless circuitous ramblings during our walks home from weekend writing sessions and allowing me the space to further form my thoughts. -

Sound American | SA Issue 6: Five Questions with Nicolas Collins

SOUND AMERICAN ABOUT THIS ISSUE JULIUS EASTMAN'S PRELUDE TO JOAN D'ARC + TOM JOHNSON'S RATIONAL MELODIES + GÉRARD GRISEY'S PROLOGUE TO LES ESPACE ACOUSTIQUE + ANTOINE BEUGER'S KEINE FERNEN MEHR + STEVE LACY'S DUCKS + FOUR SAXOPHONES ON BODY AND SOUL FIVE QUESTIONS: KURT GOTTSCHALK ABOUT OUR CONTRIBUTORS STORE SUBSCRIBE TO DRAM ARCHIVE OF PAST ISSUES + SA Issue 6: Five Questions with Nicolas Collins FIVE QUESTIONS WITH NICOLAS COLLINS Nic Collins: Photo by Viola Rusche New York born and raised, Nicolas Collins studied composition with Alvin Lucier at Wesleyan University, worked for many years with David Tudor, and has collaborated with numerous soloists and ensembles around the world. He lived most of the 1990s in Europe, where he was Visiting Artistic Director of Stichting STEIM (Amsterdam), and a DAAD composer-in-residence in Berlin. Since 1997 he has been editor-in-chief of the Leonardo Music Journal, and since 1999 a Professor in the Department of Sound at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His book, Handmade Electronic Music – The Art of Hardware Hacking (Routledge), has influenced emerging electronic music worldwide. Collins has the dubious distinction of having played at both CBGB and the Concertgebouw. Visit Nic at: www.nicolascollins.com ***** Five Questions with... is a feature of Sound American where I bother a very busy person until they answer a handful of queries around the issue's topic. This issue features composer, educator, and writer Nicolas Collins. Collins is best known for his ability to find music in the inner workings of everyday electronic objects. CD players become laser turntables, laptop motors create instant electronic music, and the laying of hands on circuits control unholy manipulations of children's toys. -

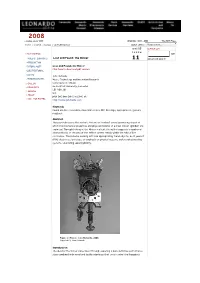

The Mincer by John Richards

22 00 00 88 -- online since 1993 ISSN NO : 1071 - 4391 The MIT Press Home > Journal > Essays > LEA-LMJ Special QUICK LINKS : Please select... vv oo l l 11 55 SEARCH LEA ii ss ss uu ee LEA E-JOURNAL GO TABLE OF CONTENTS LL oo ss t t aa nn dd FF oo uu nn dd : : t t hh ee MM i i nn cc ee r r 11 Advanced Search INTRODUCTION EDITOR'S NOTE LL oo ss t t aa nn dd FF oo uu nn dd : : t t hh ee MM i i nn cc ee r r Click here to download pdf version. GUEST EDITORIAL ESSAYS John Richards ANNOUNCEMENTS Music, Technology and Innovation Research :: GALLERY CentreSchool of Music :: RESOURCES De Montfort University, Leicester LE1 9BH, UK :: ARCHIVE U.K. :: ABOUT jrich [at] dmu [dot] ac [dot] uk :: CALL FOR PAPERS http://www.jsrichards.com KK ee yy ww oo r r dd s s Found art, live electronics, musical interface, DIY, bricolage, appropriation, gesture, feedback AA bb s s t t r r a a c c t t This paper discusses the author’s Mincer: an ‘evolved’ sound generating object of which the mechanical properties and physical material of a meat mincer (grinder) are exploited. Through looking at the Mincer in detail, the author suggests a number of characteristics of the device that reflect current trends within the field of live electronics. This includes working with and appropriating found objects, do-it-yourself (DIY) electronics, bricolage, an emphasis on physical gesture, and sound generating systems celebrating super-hybridity. -

Towards the Beat of a Different Drummer: a Journey Into the Loss of Fidelity in Drums and Electronics

TOWARDS THE BEAT OF A DIFFERENT DRUMMER: A JOURNEY INTO THE LOSS OF FIDELITY IN DRUMS AND ELECTRONICS Rodrigo Constanzo University of Manchester Oxford Road Manchester, M13 9PL [email protected] ABSTRACT defunct, Experimental Musical Instruments Journal2. In that book there was a chapter on circuit-bending that In this paper, the author describes his explorations and really excited me. I had always wanted to learn more experiments in turning an acoustic drum-set into an about electronics, and circuit-bending offered an expressive tool for electroacoustic improvisation. This is approachable entry point into the subject. Listening to primarily achieved through the addition of DIY and lo-fi examples of circuit-bending, where the nostalgic sounds electronics, as well as DIY acoustic and electroacoustic of electronic toys shattered into the fragmented and instruments to the drum-set. The author details how he chaotic sounds of the future, resonated deeply with me. I began building and modifying instruments and goes into immediately opened the Casio keyboard that had been detail on the conception and execution of some of his gathering dust in my closet and started probing away. most recent creations, where alternative interfaces for The results were very disappointing at first, as the only electronics are explored. Additionally he provides thing I could get the keyboard to do, through short- insight into his own methods for the practical integration circuiting, was crash. of a large range of sound objects and instruments into his improvisation. The author concludes with his plans for future instruments and explorations predominately dealing with Arduinos and Apple iOS devices. -

Moogfest Cover Flat.Indd

In plaIn sIght JustIce m o o g f e s t Your weekend-long dance eVents at Moog FactorY reMIX Masters partY starts here Moog Music makes Moog instruments, including the Little Phatty and Voyager. The factory is French electro-pop duo Justice is the unofficial start to Moogfest: the band’s American tour in downtown Asheville at 160 Broadway St., where the analog parts are manufactured by hand. brings them to the U.S. Cellular Center on Thursday, Oct. 25. And while the show isn’t part of This year's Moogfest (the third for the locally held immersion course in electronic music) Check out these events happening there: the Moogfest lineup, festival attendees did have first dibs on pre-sale tickets. brings some changes — a smaller roster, for one. And no over-the-top headliner. No Flaming Even without a Moogfest ticket, you can go to MinimoogFest. It’s free and open to the public. Gaspard Augé and Xavier de Rosnay gained recognition back in ‘03 when they entered their Lips. No Massive Attack. Think of it as the perfect opportunity to get to know the 2012 per- Check out DJ sets by locals Marley Carroll and In Plain Sight (winners of the Remix Orbital for remix of “Never Be Alone” by Simian in a college radio contest. Even before Justice’s ‘07 debut, formers better. It's also a prime chance to check out some really experimental sounds, from Moogfest contest), along with MSSL CMMND (featuring Chad Hugo from N.E.R.D. and Daniel †, was released, they’d won a best video accolade at the ‘06 MTV Europe Music Awards. -

Electronics in Music Ebook, Epub

ELECTRONICS IN MUSIC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK F C Judd | 198 pages | 01 Oct 2012 | Foruli Limited | 9781905792320 | English | London, United Kingdom Electronics In Music PDF Book Main article: MIDI. In the 90s many electronic acts applied rock sensibilities to their music in a genre which became known as big beat. After some hesitation, we agreed. Main article: Chiptune. Pietro Grossi was an Italian pioneer of computer composition and tape music, who first experimented with electronic techniques in the early sixties. Music produced solely from electronic generators was first produced in Germany in Moreover, this version used a new standard called MIDI, and here I was ably assisted by former student Miller Puckette, whose initial concepts for this task he later expanded into a program called MAX. August 18, Some electronic organs operate on the opposing principle of additive synthesis, whereby individually generated sine waves are added together in varying proportions to yield a complex waveform. Cage wrote of this collaboration: "In this social darkness, therefore, the work of Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff continues to present a brilliant light, for the reason that at the several points of notation, performance, and audition, action is provocative. The company hired Toru Takemitsu to demonstrate their tape recorders with compositions and performances of electronic tape music. Other equipment was borrowed or purchased with personal funds. By the s, magnetic audio tape allowed musicians to tape sounds and then modify them by changing the tape speed or direction, leading to the development of electroacoustic tape music in the s, in Egypt and France.