ANZCOR Guideline 7 – Automated External Defibrillation in Basic Life Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Access Defibrillation/AED Program Implementation Guide

Public Access Defibrillation/AED Program Implementation Guide There are 4 key elements to establishing a Public Access Defibrillation program. These include: Having designated rescuers trained in CPR and in how to use an automated external defibrillator (AED) Having a physician to provide medical oversight and direction Integrating your program with the local emergency medical services (EMS) system Using and maintaining the AED(s) according to the manufacturers specifications Steps: 1. Gain consensus Within your company or organization begin to identify the key decision makers and arrange a meeting to gain support. The American Heart Association or your local EMS Agency can assist you with presentation materials. 2. Review the law and regulations Review Federal, State and local laws and regulations regarding Public Access Defibrillation program requirements. Consult your local Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Agency The California laws ang regulations that pertain to AEDs are Title 22, and AB 658. 3. Consult your local Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Agency The local EMS Agency can provide you with information regarding training, purchasing AEDs, medical direction and laws and regulations. 4. Identify your response team Identify who would be most likely to respond in an emergency – this will help determine how and where AEDs are mounted or stored. 5. Select equipment and vendor Some considerations in selecting the AED may include: Reputation of the AED manufacturer for the product’s quality and customer service, compatibility with the equipment used in the local EMS system, and ease of operation of the AED. 6. Design Policies and Procedures These may include: Who manages the AED program When the AED should be used, when it should not be used Training required to use the AED Locations of AEDs and other equipment (such as gloves and pocket mask for CPR) Notification process for internal AED responders and external emergency medical services responders Maintenance schedule for equipment Training and refresher training policies 7. -

Delaying Defibrillation to Give Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation to Patients with Out-Of-Hospital Ventricular Fibrillation a Randomized Trial

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Delaying Defibrillation to Give Basic Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation to Patients With Out-of-Hospital Ventricular Fibrillation A Randomized Trial Lars Wik, MD, PhD Context Defibrillation as soon as possible is standard treatment for patients with ven- Trond Boye Hansen tricular fibrillation. A nonrandomized study indicates that after a few minutes of ven- Frode Fylling tricular fibrillation, delaying defibrillation to give cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) first might improve the outcome. Thorbjørn Steen, MD Objective To determine the effects of CPR before defibrillation on outcome in pa- Per Vaagenes, MD, PhD tients with ventricular fibrillation and with response times either up to or longer than Bjørn H. Auestad, PhD 5 minutes. Design, Setting, and Patients Randomized trial of 200 patients with out-of- Petter Andreas Steen, MD, PhD hospital ventricular fibrillation in Oslo, Norway, between June 1998 and May 2001. ARLY DEFIBRILLATION IS CRITICAL Patients received either standard care with immediate defibrillation (n=96) or CPR first for survival from ventricular fi- with 3 minutes of basic CPR by ambulance personnel prior to defibrillation (n=104). If initial defibrillation was unsuccessful, the standard group received 1 minute of CPR brillation. The survival rate de- before additional defibrillation attempts compared with 3 minutes in the CPR first group. creases by 3% to 4% or 6% to E10% per minute depending on whether Main Outcome Measure Primary end point was survival to hospital discharge. Sec- ondary end points were hospital admission with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation 1,2 1-year survival, and neurological outcome. A prespecified analysis examined sub- (CPR) is performed. -

The Refractory VF Arrest Patient: a Review of the Current Treatment

1/24/2018 The Refractory VF Arrest Patient: A Review of the Current Treatment Options Marc Conterato, MD, FACEP Office of the Medical Director North Memorial Health Ambulance Service DISCLOSURE STATEMENT • Board Member, MN Resuscitation Consortium - Images of any commercial devices or medications are for illustration purposes only. The inclusion of such images in this presentation does not imply endorsement of any specific device or company. 2 Objectives • Delineate Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation (RVF) • Recurrent VF versus Refractory VF • What is “Electrical Storm” • Current Pre-hospital treatments • Additional hospital treatments • Dual/Double Sequential Defibrillation • ECMO/ECLS-A New Hope? 3 1 1/24/2018 A Standard Scenario • 55 YOF collapses at stop light, and her car rolls into the car in front of her. Airbags do not deploy, and bystanders find her slumped over the steering wheel and pulseless. • First responder/bystanders start CPR, and deliver three AED shocks prior to EMS arrival. • On EMS arrival, a fourth shock is delivered, an IO and alternative airway placed. Automated CPR started. • Epinephrine 2 mg (total) and Amiodarone 300 mg given, and the patient remains in VF. • Patient downtime is now ~25 minutes, and repeat evaluation reveals persistent VF. 4 What are your options • Continue CPR for a total of 30 minutes with recurrent defibrillations, additional epinephrine, bicarbonate and Amiodarone? • “Load and Go” to the local hospital with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation? • “Load and Go” to the local CCL (Cardiac Cath Lab) hospital with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation, with possible PCI with ongoing CPR? • Call HEMS unit for transfer to CCL hospital, but can they continue effective CPR in the helicopter? • “Load and Go” to a ECMO/ECLS center with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation, on the basis they can accept the patient and continue resuscitation? 5 Defining the problem: What is recurrent versus refractory VF (RVF)? • Recurrent VF is a rhythm that terminates with cardioversion, but then recurs rapidly. -

Resuscitation and Defibrillation

AARC GUIDELINE: RESUSCITATION AND DEFIBRILLATION AARC Clinical Practice Guideline Resuscitation and Defibrillation in the Health Care Setting— 2004 Revision & Update RAD 1.0 PROCEDURE: signs, level of consciousness, and blood gas val- Recognition of signs suggesting the possibility ues—included in those conditions are or the presence of cardiopulmonary arrest, initia- 4.1 Airway obstruction—partial or complete tion of resuscitation, and therapeutic use of de- 4.2 Acute myocardial infarction with cardio- fibrillation in adults. dynamic instability 4.3 Life-threatening dysrhythmias RAD 2.0 DESCRIPTION/DEFINITION: 4.4 Hypovolemic shock Resuscitation in the health care setting for the 4.5 Severe infections purpose of this guideline encompasses all care 4.6 Spinal cord or head injury necessary to deal with sudden and often life- 4.7 Drug overdose threatening events affecting the cardiopul- 4.8 Pulmonary edema monary system, and involves the identification, 4.9 Anaphylaxis assessment, and treatment of patients in danger 4.10 Pulmonary embolus of or in frank arrest, including the high-risk de- 4.11 Smoke inhalation livery patient. This includes (1) alerting the re- 4.12 Defibrillation is indicated when cardiac suscitation team and the managing physician; (2) arrest results in or is due to ventricular fibril- using adjunctive equipment and special tech- lation.1-5 niques for establishing, maintaining, and moni- 4.13 Pulseless ventricular tachycardia toring effective ventilation and circulation; (3) monitoring the electrocardiograph and recogniz- -

The Transthoracic Impedance Cardiogram Is a Potential Haemodynamic Sensor for an Automated External Defibrillator

European Heart Journal (1998) 19, 1879–1888 Article No. hj981199 The transthoracic impedance cardiogram is a potential haemodynamic sensor for an automated external defibrillator P. W. Johnston*, Z. Imam†, G. Dempsey†, J. Anderson† and A. A. J. Adgey *Regional Medical Cardiology Centre, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast; †Northern Ireland Bioengineering Centre, Belfast, Northern Ireland Aims The American Heart Association has endorsed the agonal rhythm (20), electromechanical dissociation (22), concept of Public Access Defibrillation. However, there ventricular tachycardia (27) and sinus rhythm (5). These have been reports of inappropriate direct current shocks rhythms were divided into those associated with haemo- from automatic external defibrillators. The specificity of dynamic collapse i.e. no pulse — asystole, ventricular fibril- automatic external defibrillators for shockable rhythms lation, agonal rhythm, electromechanical dissociation and may be improved by the incorporation of a haemodynamic shockable ventricular tachycardia (associated with loss of sensor. consciousness, pulselessness or a systolic blood pressure of <80 mmHg) (Group 1) and those associated with a satis- Methods and Results This study examined the use of four factory cardiac output i.e. non-shockable ventricular tachy- parameters extracted from the impedance cardiogram i.e. cardia (conscious with a pulse) and sinus rhythm (Group 2). Peak dz/dt (the peak of the impedance cardiogram On univariate analysis each of the four impedance cardio- measured from the line dz/dt=0 Ùs"1), Peak-trough (the gram parameters were significantly greater in Group 2 than peak-to-trough measurement of the impedance cardiogram Group 1 (P<0·001). On multivariate analysis the par- Ùs"1), Area 1 (the area under the C wave of the impedance ameters which best differentiated the two groups were Area cardiogram above the line dz/dt=0 mÙ) and Area 2 (the 1 and Peak-trough. -

PUBLIC ACCESS to AUTOMATED EXTERNAL DEFIBRILLATORS (Aeds) FACTS

POSITION STATEMENT PUBLIC ACCESS TO AUTOMATED EXTERNAL DEFIBRILLATORS (AEDs) FACTS • Cardiac refers to the heart. Arrest means stop. Sudden cardiac arrest is the sudden and unexpected loss of heart function. • Signs of cardiac arrest include: no breathing or only gasping, no movement, and no pulse. • Up to 40,000 cardiac arrests occur each year in Canada. That’s one cardiac arrest every 12 minutes. Without rapid and appropriate treatment, most of these cardiac arrests will result in death. Thousands of lives could be saved through public access to automated external defibrillators. • An automated external defibrillator (AED) is a small, portable device used to identify cardiac rhythms and deliver a shock to correct abnormal electrical activity in the heart. As a result of the sophisticated electronics in an AED the operator will only be advised to deliver a shock if the • A landmark study of the City of Chicago airports public heart is in a rhythm which can be corrected by defibrillation. access to AED program showed survival rates as high as If a shockable rhythm is not detected, no shock can be 75%. This success is directly related to highly visible, readily given and the provider will be instructed to perform accessible automated external defibrillators for public use cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) until emergency and an integrated structured emergency response system.7 medical services arrive. • Research shows that AEDs are most effectively used by • When an AED and CPR are immediately available, the trained individuals. However, AEDs are safe and easy to use chance of survival from sudden cardiac arrest is substantially by almost anyone. -

Sudden Cardiac Arrest a Treatable Public Health Crisis Ê Ê

Sudden Cardiac Arrest A Treatable Public Health Crisis Table of Contents Overview Part I: Medical Issues Definition and Incidence of Sudden Cardiac Arrest Treatment of Sudden Cardiac Arrest The Evolution of Rapid Emergency Defibrillation Part II: Economic Issues Part III: Technology Issues The Automatic External Defibrillator (AED) Breakthrough AED Technology: Key Criteria Part IV: The Ultimate Goal—Rapid And Effective Response Summary and Conclusions Glossary References "Sudden Cardiac Arrest: A Treatable Public Health Crisis" was written under an educational grant from Heartstream, Inc. by Communicore, an independent medical communications organization. It is one White Paper in a series published by Communicore to explore emerging issues in healthcare, generate awareness about these topics, and facilitate discussion about possible solutions. For more information about this or any other Communicore product or service e-mail: [email protected]. Copyright © 1996, Communicore, 2 Union Square, 601 Union Street, Suite 4600, Seattle, WA 98101 USA. Any reproduction without permission is prohibited. Overview Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) remains a major unresolved public health problem; each year in the United States alone, sudden cardiac arrest strikes more than 350,000 people—nearly 1,000 per day—making it the single leading cause of death.1,2 Due in part to the unexpectedness with which SCA strikes, most of these victims die before reaching a hospital. Currently, the chances of surviving an SCA in the United States are less than one in 20. Experts agree that many of the deaths due to SCA are preventable and that available technology, if appropriately applied, could reduce them significantly at a relatively low cost.3 The vast majority of sudden cardiac arrests are due to abnormal heart rhythms called arrhythmias, of which ventricular fibrillation is the most common. -

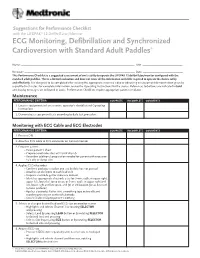

ECG Monitoring, Defibrillation and Synchronized Cardioversion with Standard Adult Paddles*

Suggestions for Performance Checklist with the LIFEPAK® 12 Defibrillator/Monitor ECG Monitoring, Defibrillation and Synchronized Cardioversion with Standard Adult Paddles* Name: _____________________________________________________________________________ Unit: ______________________________ Reviewer: ___________________________________________________________________________ Date: ______________________________ This Performance Checklist is a suggested assessment of one’s ability to operate the LIFEPAK 12 defibrillator/monitor configured with the standard adult paddles. This is a limited evaluation and does not cover all the information and skills required to operate the device safely and effectively. It is designed to be completed after viewing the appropriate inservice video or observing an equipment demonstration given by a qualified instructor. For complete information, review the Operating Instructions for the device. References to buttons are indicated in bold and display messages are indicated in italics. Performance Checklists require appropriate patient simulator. Maintenance PERFORMANCE CRITERIA COMPLETE INCOMPLETE COMMENTS 1. Locates equipment and accessories, operator’s checklist and Operating Instructions 2. Demonstrates equipment tests according to daily test procedure Monitoring with ECG Cable and ECG Electrodes PERFORMANCE CRITERIA COMPLETE INCOMPLETE COMMENTS 1. Presses ON 2. Attaches ECG cable to ECG connector on front of monitor 3. Prepares patient • Bares patient’s chest • Prepares electrode sites with brisk dry rub -

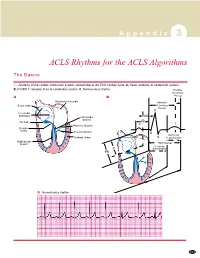

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

APLS Simulation Scenarios

MODULE Simulation Scenarios This material is made available as part of the professional education programs of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Emergency Physicians. No endorsement of any product or service should be inferred or is intended. Every effort has been made to ensure that contributors to the APLS materials are knowledgeable authorities in their fields. Readers are nevertheless advised that the statements and opinions expressed are provided as guidelines and should not be construed as official policy of the American Academy of Pediatrics or the American College of Emergency Physicians. The recommendations in these accompanying materials do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, nature of medical oversight, and local protocols, may be appropriate. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Emergency Physicians, and the authors here within disclaim any liability or responsibility for the consequences of any actions taken in reliance on these statements, opinions, or contents contained within these materials. © 2015 by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Emergency Physicians MODULE Simulation Scenarios Contents Adrenal Insufficiency 1 Blunt Abdominal Trauma—Hypovolemic Shock 4 Cardiogenic Shock Due to Congenital Heart Disease 8 Altered Mental Status 10 Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Cerebral Edema 12 Hyperthermia 15 Hypothermia—Near Drowning 18 Iron Overdose 22 Myocarditis—Cardiogenic Shock 25 Occult -

The Powerheart® Family of Products

The Powerheart® family of products AT THE HEART OF SAVING LIVES.TM When you bring AEDs to your facility, you empower teachers, employees, and/or bystanders all to become part of the chain of survival According to the American Heart Association (AHA) and European Resuscitation Council (ERC), a sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) victim requires 911 defibrillation to stop ventricular fibrillation (VF), an often-fatal heart abnormality. The sooner the defibrillation, the better the victim’s chances of survival – precisely why having your own automated external defibrillator (AED) to use while you're waiting for emergency medical responders is so important. Time is the critical factor Several studies document the effects of time to defibrillation and the effects of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on surviving SCA. For every minute that passes between collapse and defibrillation, survival rates for witnessed VF SCA decrease 7 to 10 percent if no CPR is provided. VF rarely converts spontaneously. It’s ultimately a defibrillator that saves lives. Make sure you have one when it’s needed. 100 80 60 40 Percent Survival Rate Percent 20 0 12345678910 Minutes to Defibrillation Shock Did you know? According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 13 percent of all workplace fatalities result from sudden cardiac arrest. 2 The Powerheart® family of defibrillators Most anyone can operate a Powerheart AED G3 Plus In the chaos that follows SCA, concerned but untrained bystanders are scared. Do they know what to do? There’s a life on the line! We designed the Powerheart AED G3 Plus with RescueCoach™ voice prompts to talk rescuers through the steps. -

Trauma Triage Guideline 07/01/12

Larry Meredith, Ph.D., Director DIVISION OF PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES Date: June 29, 2012 To: Holders of EMS Policy and Procedure Manuals From: Bill Teufel, MD EMS Agency Medical Director Subject: Update to Policy Manual, Change Notice #31 Enclosed please find Update #31 to the EMS Policy and Procedure Manual. These new and revised policies and procedures are effective July 1, 2012. Please update the Record of Change page and replace the Table of Contents and Signature page. Revised Policies and Procedures include: 4613 Trauma Triage & Destination C 1 Ventricular Fibrillation / Pulseless Guideline Ventricular Tachycardia ALS PR 1 Expanded Scope C 2 Pulseless Electrical Activity ALS PR 2 Adult Intraosseous Procedure C 3 Asystole ALS PR 3 Adult Oral Intubation C 8 Chest Pain / Acute Coronary Syndrome ALS PR 7 Procedure for Intranasal Medications C 9 STEMI ALS PR 11 External Cardiac Pacing GPC 13 Spinal Immobilization Procedure M 6 Sepsis ALS PR 14 King Airway Procedure N 4 Cerebrovascular Accident ATG 1 Routine Medical Care P 03 Pediatric Respiratory Distress ATG 2 Adult Pain Management P 8 Pediatric Allergic Reaction ATG 3 Adult Sedation R 2 Airway Obstruction ATG 5 Adult Intraosseous Infusion ATG 6 Determination of Death - ALS ATG 7 Adult Medications Deleted Policies include: ALS PR 5 Cricothyroidotomy Procedure SPECIAL NOTIFICATION: The addition of the following items into EPCIS will not occur until mid-July and will need to be documented in the narrative until that time: M6 Sepsis, temperature, and Lidocaine 2% The following policies were revised only to reflect the deletions of the Impedance Threshold Device and Cricothyroidomy Procedure: ALS PR 1, ALS PR 14, P 03, and R 2 If you have not received training on these changes, please contact your CQI Liaison or Training Officer.