The Attainment of Christian Perfection As a Wesleyan/ Holiness Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Other Problems from a British Perspective: 'Jewishness', Jesus, And

G. Crossley, James. "Other Problems from a British Perspective: ‘Jewishness’, Jesus, and the New Perspective on Paul." : Identities and Ideologies in Early Jewish and Christian Texts, and in Modern Biblical Interpretation. Ed. Katherine M Hockey and David G Horrell. London: T&T CLARK, 2018. 130–145. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567677334.0015>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 02:39 UTC. Copyright © Katherine M. Hockey and David G. Horrell 2018. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Ethnicity, Race, Religion Other Problems from a British Perspective 7 Other Problems from a British Perspective: ‘Jewishness’, Jesus, and the New Perspective on Paul James G. Crossley In terms of discourses concerning ‘race’ in the history of New Testament studies, the relationship between (on the one hand) Jesus, Paul, and the early church and (on the other) an assumed ‘Jewish background’ has been dominant. Over the past forty years, this relationship has been understood against the background of a Judaism often constructed in ways inspired by debates about the New Perspective on Paul. The story of the New Perspective on Paul, and its accompanying constructions of Judaism, is familiar enough to New Testament scholars. E. P. Sanders’ Paul and Palestinian Judaism challenged the dominant construction of Judaism in Lutheran-influenced analyses of Paul in which Judaism was negatively stereotyped as legalistic in contrast to the loving religion of grace advocated by Paul. -

Incorporated Righteousness: a Response to Recent Evangelical Discussion Concerning the Imputation of Christ’S Righteousness in Justification

JETS 47/2 (June 2004) 253–75 INCORPORATED RIGHTEOUSNESS: A RESPONSE TO RECENT EVANGELICAL DISCUSSION CONCERNING THE IMPUTATION OF CHRIST’S RIGHTEOUSNESS IN JUSTIFICATION michael f. bird* i. introduction In the last ten years biblical and theological scholarship has witnessed an increasing amount of interest in the doctrine of justification. This resur- gence can be directly attributed to issues emerging from recent Protestant- Catholic dialogue on justification and the exegetical controversies prompted by the New Perspective on Paul. Central to discussion on either front is the topic of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness, specifically, whether or not it is true to the biblical data. As expected, this has given way to some heated discussion with salvos of criticism being launched by both sides of the de- bate. For some authors a denial of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as the sole grounds of justification amounts to a virtual denial of the gospel itself and an attack on the Reformation. Others, by jettisoning belief in im- puted righteousness, perceive themselves as returning to the historical mean- ing of justification and emancipating the Church from its Lutheranism. In view of this it will be the aim of this essay, in dialogue with the main pro- tagonists, to seek a solution that corresponds with the biblical evidence and may hopefully go some way in bringing both sides of the debate together. ii. a short history of imputed righteousness since the reformation It is beneficial to preface contemporary disputes concerning justification by identifying their historical antecedents. Although the Protestant view of justification was not without some indebtedness to Augustine and medieval reactions against semi-Pelagianism, for the most part it represented a theo- logical novum. -

John Wesley's Teaching Concerning Perfection Edward W

JOHN WESLEY'S TEACHING CONCERNING PERFECTION EDWARD W. H. VICK Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan Wesley has often been characterized as Arminian rather than as Calvinistic. The fact that he continuously called for repentance from sin, published a journal called the Arminian Magazine, was severe in his strictures against predestination and unconditional election, engaged in controversial cor- respondence with Whitefield over the matter of election, perfection and perseverance seem to indicate a great gulf between his teaching and that of Calvin. Gulf there may be, but it need not be made to appear wider at certain points than can justly be claimed. The fact is that exclusive attention to his opposition to predestination may lead to neglect of his teaching on the relationship between faith and grace. This is not to deny that Wesley was opposed to important Calvinistic tenets. In his sermon on Free Grace, delivered in 1740, he states why he is opposed to the doctrine of pre- destination : (I) it makes preaching vain, needless for the elect and useless for the non-elect ; (2) it takes away motives for following after holiness ; (3) it tends to increase sharpness of temper and contempt for those considered to be outsiders ; (4) it tends to destroy the comfort of religion ; (5) it destroys zeal for good works ; (6) it makes the whole Christian revelation unnecessary and (7) self-contradictory ; (8) it represents the Lord as saying one thing and meaning J. Wesley, Sermons on Several Occasions, I (New York, 1827)~ 13-19. 202 EDWARD W. H. VICK another: God becomes more cruel and unjust than the devil. -

The New Perspective on Paul and the Correlation with the Book of James

Running Head: NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL AND JAMES 1 The New Perspective on Paul and the Correlation with the Book of James Zach Scott A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2017 NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL AND JAMES 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Mark D. Allen, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Michael J. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Craig Q. Hinkson, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ David E. Schweitzer, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL AND JAMES 3 Abstract The New Perspective on Paul is a new theory of how to interpret the Pauline epistles through the lens of first century Judaism. Three of the leading scholars that hold to the New Perspective are E.P. Sanders, James D.G. Dunn, and N.T. Wright. These men have done their best to defend the New Perspective of Paul, but have not adequately used, or explained the arguments set forth in the book of James, specifically found in James 2:14-26. The New Perspective fails to either give an analysis of James through the proposed lens of the New Perspective, or show how the book of James affects the New Perspective on Paul overall. NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL AND JAMES 4 The New Perspective on Paul and the Correlation with the Book of James The Bible is an extremely complex and intricate piece of literature. -

Theological Contributions of John Wesley to the Doctrine of Perfection

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 51, No. 2, 301-310. Copyright © 2013 Andrews University Press. THEOLOGICAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF JOHN WESLEY TO THE DOCTRINE OF PERFECTION THEODORE LEVTEROV Loma Linda University Loma Linda, California Introduction The doctrine of perfection is biblically based. In Matt 5:48 (NIV), Jesus declares, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” However, the meaning of the term “perfection” is contested, with many different interpretations ranging from one extreme to another.1 At one end of the spectrum, it has been concluded that perfection and Christian growth is not possible, while at the other it is thought that humans can attain a state of sinless perfection. Within this range of understandings, scholars agree that no one has better described the biblical doctrine of perfection than John Wesley. For example, Rob Staples proposes that this doctrine “represents the goal of Wesley’s entire religious quest.”2 Albert Outler notes that “the chief interest and signifi cance of Wesley as a theologian lie in the integrity and vitality of his doctrine as a whole. Within that whole, the most distinctive single element was the notion of ‘Christian perfection.’”3 Harald Lindstrom indicates that “the importance of the idea of perfection to Wesley is indicated by his frequent mention of it: in his sermons and other writings, in his journals and letters, and in the hymn books he published with his brother Charles.”4 John Wesley himself affi rmed that “this doctrine is the grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called Methodists; and for the sake of propagating this chiefl y He appeared to have raised us up.”5 This article will examine Wesley’s basic contributions to the doctrine of perfection. -

ADM Jesus Then and Now 2 Lectures

JESUS Then and Now Rev Dr John Dickson Senior Minister, St Andrew’s Roseville Lecturer, Historical Jesus, Sydney University Visiting Academic (2017-18), Faculty of Classics, Oxford University 1 HISTORY versus THEOLOGY 2 3 HISTORY OF RESEARCH ON THE HISTORICAL JESUS 4 Luke 1:1-4. Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. Therefore, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, it seemed good also to me to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught. 5 6 The consummate textual and redactional scholar of antiquity Origen of Alexandria and Caesarea (AD 185-253) 7 8 The Jesus of history and the ‘Christ’ of apostolic invention Text Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694-1768) 9 The Gospels’ story as ‘myth’ David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874) Jesus. the wise ethical teacher Joseph Ernest Renan (1823-1892) The priority of Mark and the Q-theory Heinrich Julius Holtzmann (1832-1910) The messianic ‘secret’ invented by the Gospel writers William Wrede (1859-1906) Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) The ‘Jesus’ proposed by scholars from Reimarus to Wrede is “a figure designed by rationalism, endowed with life by liberalism, and clothed by modern theology in an historical garb.” Kaysersberg, France/Germany 15 16 The life and teaching of Jesus are of secondary importance to Christian faith Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976) How much of Christianity’s post-Easter faith is supported by the Gospels’ pre-Easter story? Ernst Käsemann (1906-1998) The criterion of dissimilarity states that material in the Gospels which is markedly different from both Judaism and the early church is likely to have come from Jesus himself. -

The New Perspective on Paul: Its Basic Tenets, History, and Presuppositions

TMSJ 16/2 (Fall 2005) 189-243 THE NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL: ITS BASIC TENETS, HISTORY, AND PRESUPPOSITIONS F. David Farnell Associate Professor of New Testament Recent decades have witnessed a change in views of Pauline theology. A growing number of evangelicals have endorsed a view called the New Perspective on Paul (NPP) which significantly departs from the Reformation emphasis on justification by faith alone. The NPP has followed in the path of historical criticism’s rejection of an orthodox view of biblical inspiration, and has adopted an existential view of biblical interpretation. The best-known spokesmen for the NPP are E. P. Sanders, James D. G. Dunn, and N. T. Wright. With only slight differences in their defenses of the NPP, all three have adopted “covenantal nomism,” which essentially gives a role in salvation to works of the law of Moses. A survey of historical elements leading up to the NPP isolates several influences: Jewish opposition to the Jesus of the Gospels and Pauline literature, Luther’s alleged antisemitism, and historical-criticism. The NPP is not actually new; it is simply a simultaneous convergence of a number of old aberrations in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. * * * * * When discussing the rise of the New Perspective on Paul (NPP), few theologians carefully scrutinize its historical and presuppositional antecedents. Many treat it merely as a 20th-century phenomenon; something that is relatively “new” arising within the last thirty or forty years. They erroneously isolate it from its long history of development. The NPP, however, is not new but is the revival of an old ideology that has been around for the many centuries of church history: the revival of works as efficacious for salvation. -

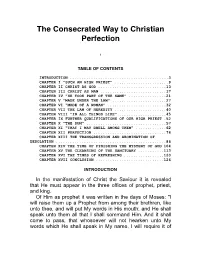

The Consecrated Way to Christian Perfection

The Consecrated Way to Christian Perfection 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................3 CHAPTER I "SUCH AN HIGH PRIEST" .......................9 CHAPTER II CHRIST AS GOD .............................13 CHAPTER III CHRIST AS MAN ............................17 CHAPTER IV "HE TOOK PART OF THE SAME" ................21 CHAPTER V "MADE UNDER THE LAW" .......................27 CHAPTER VI "MADE OF A WOMAN" .........................32 CHAPTER VII THE LAW OF HEREDITY ......................40 CHAPTER VIII "IN ALL THINGS LIKE" ....................45 CHAPTER IX FURTHER QUALIFICATIONS OF OUR HIGH PRIEST .52 CHAPTER X "THE SUM" ..................................57 CHAPTER XI "THAT I MAY DWELL AMONG THEM" .............62 CHAPTER XII PERFECTION ...............................76 CHAPTER XIII THE TRANSGRESSION AND ABOMINATION OF DESOLATION ...............................................86 CHAPTER XIV THE TIME OF FINISHING THE MYSTERY OF GOD 104 CHAPTER XV THE CLEANSING OF THE SANCTUARY ...........113 CHAPTER XVI THE TIMES OF REFRESHING .................120 CHAPTER XVII CONCLUSION .............................126 INTRODUCTION In the manifestation of Christ the Saviour it is revealed that He must appear in the three offices of prophet, priest, and king. Of Him as prophet it was written in the days of Moses: "I will raise them up a Prophet from among their brethren, like unto thee, and will put My words in His mouth; and He shall speak unto them all that I shall command Him. And it shall come to pass, that whosoever will not hearken unto My words which He shall speak in My name, I will require it of him." Deut. 18:18,19. And this thought was continued in the succeeding scriptures until His coming. Of Him as priest it was written in the days of David: "Yet have I set ['anointed,' margin] My King upon My holy hill of Zion." Ps. -

The Holiness Movement the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Part 1

Community Bible Church Instructor: Bill Combs THE HOLINESS MOVEMENT THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY PART 1 I. INTRODUCTION A. Though the title of this series is “The Holiness Movement,” we actually will be taking a more comprehensive historical perspective. What is technically called the Holiness movement, as we will see, developed out of the Methodist Church in the middle of the 19th century (the 1800s) in American. It was an attempt to preserve the teachings on holiness of John Wesley (1703–1791), the founder of Methodism. Wesley came up with the new and unique idea of a second transforming work of grace that is distinct from and subsequent to the new birth. This second blessing of entire sanctification is just as powerful and transforming as the first transforming work of grace—the new birth or regeneration. The Methodist Church eventually forsook Wesley’s view of sanctification at the end of the 19th century, but the Holiness Movement continued to champion Wesley’s view. Part of this Holiness tradition led to what is called the Keswick (the “w” is silent) movement. It is the particular form of Holiness teaching found in the Keswick movement that is of most interest to us in our study the next few weeks. The Keswick movement began at the end of the 19th century and in the 20th century became the most common way of understanding the Bible’s teaching on holiness in fundamentalism and most churches in the broader evangelical tradition—Baptist churches, Bible churches, some Presbyterian churches (also many parachurch organizations, such as Campus Crusade for Christ). -

Luke and Early Catholicism*

4 LUKE AND EARLY CATHOLICISM LUKE AND EARLY CATHOLICISM* LEON MORRIS* The publication of Philipp Viel- ways defined and the discussion hauser's essay, "On the Taulinism' may become a trifle confused ac of Acts",2 sparked off a lively de cordingly. The term is not new and bate in Lucan studies. Vielhauer John H. Elliott notes its use at least held that Acts did not come from a as far back as Ferdinand Christian disciple and friend of Paul; it is a Bauer.5 But it has had a much later writing emanating not from greater currency during recent the primitive church but from the years. E. Käsemann sees it this developing catholic church. Hans way: "Early Catholicism means Conzelmann's important book, The that transition from earliest Chris Theology of St Luke,3 gave the de tianity to the so-called ancient bate some impetus. It cannot be Church, which is completed with said that anything approaching un the disappearance of the imminent animity has been reached. Indeed expectation (i.e. of the parousia)."6 the situation was well summed up This puts all the emphasis on the in the title of W.C. van Unnik's con attitude to the parousia. Hans Con- tribution to the Paul Schubert zelmann emphasizes other aspects Festschri/t "Luke-Acts, A Storm of the church's life: Center in Contemporary Scholar The relationship of the Church to ship".4 This was published in 1966, the eschatological future loses in but the situation has not greatly importance in comparison with changed in the intervening period, the present possession of 'means at least in this respect. -

What Is Classical Arminianism?

SEEDBED SHORTS Kingdom Treasure for Your Reading Pleasure Copyright 2014 by Roger E. Olson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission, except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles. uPDF ISBN: 978-1-62824-162-4 3 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Roger E. Olson Roger Olson is a Christian theologian of the evangelical Baptist persuasion, a proud Arminian, and influenced by Pietism. Since 1999 he has been the Foy Valentine Professor of Christian Theology of Ethics at George W. Truett Theological Seminary of Baylor University. Before joining the Baylor community he taught at Bethel College (now Bethel University) in St. Paul, Minnesota. He graduated from Rice University (PhD in Religious Studies) and North American Baptist Seminary (now Sioux Falls Seminary). During the mid-1990s he served as editor of Christian Scholar’s Review and has been a contributing editor of Christianity Today for several years. His articles have appeared in those publications as well as in Christian Century, Theology Today, Dialog, Scottish Journal of Theology, and many other religious and theological periodicals. Among his published works are: 20th Century Theology (co-authored with the late Stanley J. Grenz), The Story of Christian Theology, The Westminster Handbook to Evangelical Theology, Arminian Theology, Reformed and Always Reforming, and Against Calvinism. He enjoys -

John Wesley on Aspects of Christian Experience After Justification

John Wesley On Aspects Of Christian Experience After Justification Owen H. Alderfer Introduction That which is regarded as unique in the thought of John " Wesley is often termed "The Doctrine of Christian Perfection. To consider this element in Wesley's thought as one idea among many ideas is to confuse the thought of this man. Wesley was obsessed with the idea of Christian perfection and its attain ability in this life. The various steps in Christian experience, as Wesley saw them, were related to perfection. An under standing of various aspects of Christian experience subsequent to justification and related to Christian perfection will be helpful in understanding the whole thought of this leader. It is an assumption of this paper that Wesley may be under stood largely in terms of his consideration and treatment of Christian experience. In Wesley's thinking there was an ideal of for believers not pattern experience , though possibly everyone discovers the ideal. To imderstand this ideal pattern of experience which he saw is to understand Wesley. The basic problem of this study is the determination of the ideal pattern of Christian experience after justification as set forth by John Wesley. This involves an effort to discover points of Christian experience which should be attained by every believer. Implied here are means necessary for attainment of such ends; further are implied alternatives which follow failure to achieve ideal ends. These are elements related to the problem at hand. Beyond the problem itself, but related to it, is a consideration of the difficulties which Wesley encountered in the presentation of his views.