Governance for Sustainable Human Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippines: Information on the Barangay and on Its Leaders, Their

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 19 September 2003 PHL41911.E Philippines: Information on the barangay and on its leaders, their level of authority and their decision-making powers (1990-2003) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa A Cultural Attache of the Embassy of the Philippines provided the attached excerpt from the 1991 Local Government Code of the Philippines, herein after referred to as the code, which describes the role of the barangay and that of its officials. As a community-level political unit, the barangay is the planning and implementing unit of government policies and activities, providing a forum for community input and a means to resolve disputes (Republic of the Philippines 1991, Sec. 384). According to section 386 of the code, a barangay can have jurisdiction over a territory of no less than 2,000 people, except in urban centres such as Metro Manila where there must be at least 5,000 residents (ibid.). Elected for a term of five years (ibid. 14 Feb. 1998, Sec. 43c; see the attached Republic Act No. 8524, Sec. 43), the chief executive of the barangay, or punong barangay enforces the law and oversees the legislative body of the barangay government (ibid. 1991, Sec. 389). Please consult Chapter 3, section 389 of the code for a complete description of the roles and responsibilities of the punong barangay. In addition to the chief executive, there are seven legislative, or sangguniang, body members, a youth council, sangguniang kabataan, chairman, a treasurer and a secretary (ibid., Sec. -

Philippines's Constitution of 1987

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Philippines's Constitution of 1987 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 ARTICLE I: NATIONAL TERRITORY . 3 ARTICLE II: DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES . 3 ARTICLE III: BILL OF RIGHTS . 6 ARTICLE IV: CITIZENSHIP . 9 ARTICLE V: SUFFRAGE . 10 ARTICLE VI: LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT . 10 ARTICLE VII: EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT . 17 ARTICLE VIII: JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT . 22 ARTICLE IX: CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS . 26 A. COMMON PROVISIONS . 26 B. THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION . 28 C. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS . 29 D. THE COMMISSION ON AUDIT . 32 ARTICLE X: LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 33 ARTICLE XI: ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS . 37 ARTICLE XII: NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY . 41 ARTICLE XIII: SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS . 45 ARTICLE XIV: EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ARTS, CULTURE, AND SPORTS . 49 ARTICLE XV: THE FAMILY . 53 ARTICLE XVI: GENERAL PROVISIONS . 54 ARTICLE XVII: AMENDMENTS OR REVISIONS . 56 ARTICLE XVIII: TRANSITORY PROVISIONS . 57 Philippines 1987 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Source of constitutional authority • General guarantee of equality Preamble • God or other deities • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. -

Sandiganbayan Quezon City

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Sandiganbayan Quezon City SIXTH DIVISION PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, SB-16-CRM-0334 Plaintiff, For: Violation of Section 7(d) of R.A. No. 6713 SB-16-CRM-0335 For: Direct Bribery - versus - Present: FERNANDEZ, SJ, JL, ANGELITO DURAN SACLOLO, JR., Chairperson BT AL. MIRANDA, J". and Accused. VIVERO, J. Promulgated: J tf X- -X DECISION FERNANDEZ, SJ, J. Accused Angelito Duran Saclolo, Jr. and Alfredo G. Ortaleza stand charged for violation of Article 210 of the Revised Penal Code^ and of Section 7(d) of R.A. No. 6713,2 for demanding and accepting the amount of PhP300,000.00 / from Ma. Linda Moya of Richworld Aire and Technologie&V 'Republic Act No. 3815 2 Code ofConduct and Ethical Standardsfor Public Officials and Employees, Februaiy 20, 1989 DECISION People vs. Saclolo et at. Criminal Case Nos. SB-16-CRM-0334 to 0335 Page 2 of63 X X Corporation (Richworld), in consideration for the immediate passage of a Sangguniang Panlungsod Resolution authorizing the construction of Globe Telecoms cell sites in Cabanatuan City. The Information in SB'16-CRM'0334 reads: For: Violation ofR.A. No. 6713, Sec. 7(d) That on April 10, 2013 or sometime prior or subsequent thereto, in the City of Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the accused, Angelito Duran Saclolo, Jr. and Alfredo Garcia Ortaleza, both public officers, being then a Member of the Sangguniang Panlungsod and concurrent Chairman of the Committee on Transportation and Communications and Secretaiy to the Sangguniang Panlungsod, respectively, of Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, while in the performance of their official functions, committing the offense in relation to their office and taking advantage of their official positions, conspiring and confederating with one another, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and criminally accept the amount of Three Hundred Thousand Pesos (P300,000.00) from Ma. -

Legal and Constitutional Disputes and the Philippine Economy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sicat, Gerardo P. Working Paper Legal and constitutional disputes and the Philippine economy UPSE Discussion Paper, No. 2007,03 Provided in Cooperation with: University of the Philippines School of Economics (UPSE) Suggested Citation: Sicat, Gerardo P. (2007) : Legal and constitutional disputes and the Philippine economy, UPSE Discussion Paper, No. 2007,03, University of the Philippines, School of Economics (UPSE), Quezon City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/46621 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Legal and Constitutional Disputes and the Philippine Economy By Gerardo P. Sicat∗ Abstract 0 I. Introduction..........................................................................................................1 II. The Constitutional framework of Philippine economic development policy since 1935 3 III. -

'14 Sfp -9 A10 :32

Srt1lltr SIXTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC (fJff1;t t,f t~t !~rrrvf:1f\l OF THE PHILIPPINES Second Regular Session '14 SfP -9 A10 :32 SENATE Senate Bill No. 2401 Prepared by the Committees on Local Government; Electoral Reform~ ang People's 'J, . ..... Participation; Finance; and Youth with Senators Ejercito, Aquino IV, Marcos Jr., Pimentel III, and Escudero, as authors thereof AN ACT ESTABLISHING ENABLING MECHANISMS FOR MEANINGFUL YOUTH PARTICIPATION IN NATION BUILDING, STRENGTHENING THE SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN, CREATING THE MUNICIPAL, CITY AND PROVINCIAL YOUTH DEVELOPMENT COUNCILS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Be it enacted by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled: 1 CHAPTER I 2 INTRODUCTORY PROVISIONS 3 Section 1, Title. - This Act shall be known as the "Youth Development 4 and Empowerment Act of 2014". 5 Section 2. Declaration of State Policies and Objectives. - The State 6 recognizes the vital role of the youth in nation building and thus, promotes 7 and protects their physical, moral, spiritual, intellectual and social well- 8 being, inculcates in them patriotism, nationalism and other desirable 9 values, and encourages their involvement in public and civic affairs. 10 Towards this end, the State shall establish adequate, effective, 11 responsive and enabling mechanisms and support systems that will ensure 12 the meaningful participation of the youth in local governance and in nation 13 building. 1 1 Section 3. Definition of Terms. - For purposes of this Act, the 2 following terms are hereby defined: 3 (a) "Commission" shall refer to the National Youth Commission 4 created under Republic Act (RA) No. -

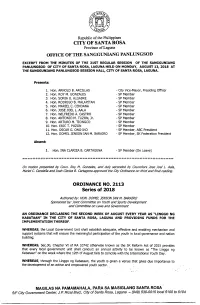

ORDINANCE NO. 2113 Series of 2018

sANti 1„, Republic of the Philippines CITY OF SANTA ROSA Province of Laguna OFFICE OF THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE 31ST REGULAR SESSION OF THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD OF CITY OF SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA HELD ON MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 AT THE SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD SESSION HALL, CITY OF SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA. Presents: 1. Hon. ARNOLD B. ARCILLAS - City Vice-Mayor, Presiding Officer 2. Hon. ROY M. GONZALES - SP Member 3. Hon. SONIA U. ALGABRE - SP Member 4. Hon. RODRIGO B. MALAPITAN - SP Member 5. Hon. MARIEL C. CENDANA - SP Member 6. Hon. JOSE JOEL L. AALA - SP Member 7. Hon. WILFREDO A. CASTRO - SP Member 8. Hon. ANTONIO M. TUZON, Jr. - SP Member 9. Hon. ARTURO M. TIONGCO - SP Member 10.Hon. ERIC T. PUZON - SP Member 11.Hon. OSCAR G. ONG-IKO - SP Member, ABC President 12.Hon. DOMEL JENSON IAN M. BARAIRO - SP Member, SK Federation President Absent: 1. Hon. INA CLARIZA B. CARTAGENA - SP Member (On Leave) On motion presented by Coun. Roy M. Gonzales, and duly seconded by Councilors Jose Joel L. Aala, Mariel C. Cendafia and Inah Clariza B. Cartagena approved the City Ordinance on third and final reading. ORDINANCE NO. 2113 Series of 2018 Authored by: HON. DOMEL JENSON IAN M. BARAIRO Sponsored by: Joint Committee on Youth and Sports Development and Committee on Laws and Government AN ORDINANCE DECLARING THE SECOND WEEK OF AUGUST EVERY YEAR AS "LINGGO NG KABATAAN" IN THE CITY OF SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA AND PROVIDING FUNDS FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION THEREOF. WHEREAS, the Local Government Unit shall establish adequate, effective and enabling mechanism and support systems that will ensure the meaningful participation of the youth in local governance and nation building; WHEREAS, Sec.30, Chapter VI of RA 10742 otherwise known as the SK Reform Act of 2015 provides that every local government unit shall conduct an annual activity to be known as "The Linggo ng Kabataan" on the week where the 12th of August falls to coincide with the International Youth Day. -

Barangay Justice Showcasing LGU Gains in Conflict Management

Gerry Roxas Foundation 1 LGU Initiatives in Barangay Justice Showcasing LGU Gains in Conflict Management AUTHORS: Zamboanga Sibugay - Engr. Venencio Ferrer Tawi-Tawi - Farson Mihasun Pagadian - Rosello Macansantos Dipolog - Arvin Bonbon Davao del Sur - Danilo Tagailo and Atty Arlene Cosape Maguindanao - Mastura Tapa South Cotabato - Bernadette Undangan and Danny Dumandagan Sarangani - Evan Campos and Jocelyn Kanda EDITOR: Ms. Gilda Ginete DESIGN AND LAYOUT: Glen A. de Castro Jacquelyn A. Aguilos Copyright @ All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission from GRF. Published by: Gerry Roxas Foundation 11/F Aurora Tower, Araneta Center Quezon City 1109, Philippines Tel: (632) 911.3101 local 7244 Fax: (632) 421.4006 www.gerryroxasfoundation.org Disclaimer: This study is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through Cooperative Agreement AID 492-A-00-09-00030. The contents are the responsibilities of the Gerry Roxas Foundation and do not necessarily reflect the United States Government and the Gerry Roxas Foundation. Gerry Roxas Foundation 2 Table of Contents Davao del Sur Initiatives from the Ground 7-14 Dipolog A Recipe for Lasting Peace in the Bottled Sardines Capital 15-26 Maguindanao GO-NGO Partnership in the Sustainability of the BJPP in Maguindanao 27-33 Pagadian “Handog -

Child Participation in the Philippines

Child Participation in the Philippines: Reconstructing the Legal Discourse of Children and Childhood by Rommel Salvador A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Rommel Salvador 2013 Child Participation in the Philippines: Reconstructing the Legal Discourse of Children and Childhood Rommel Salvador Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This thesis explores the participation of children within legal discourse by looking at how laws and policies engage or disengage children. The basic premise is that to understand children’s participation is to confront the discourse of children and childhood where we uncover underlying assumptions, interests and agendas that inform our conception of who the child is and what the experience of childhood entails. Specifically, the thesis examines child participation within the Philippine legal framework by looking at the status, conditions and circumstances of children in four contexts: family, educational system, work environment and youth justice system. It argues that our conceptions of children and childhood are not only produced from a particular discourse but in turn are productive of a particular construction and practices reflected in the legal system. In its examination, the thesis reveals a complex Philippine legal framework shaped by competing paradigms of children and childhood that both give meaning to and respond to children’s engagements. On the one hand, there is a dominant discourse based on universal patterns of development and socialization that views children as objects of adult control and influence. But at the same time, there is some concrete attraction to an emerging paradigm ii influenced by childhood studies and the child rights movement that opens up opportunities for children’s participation. -

Philippine Community Mediation, Katarungang Pambarangay

Journal of Dispute Resolution Volume 2008 Issue 2 Article 5 2008 Philippine Community Mediation, Katarungang Pambarangay Gill Marvel P. Tabucanon James A. Wall Jr. Wan Yan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Gill Marvel P. Tabucanon, James A. Wall Jr., and Wan Yan, Philippine Community Mediation, Katarungang Pambarangay, 2008 J. Disp. Resol. (2008) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr/vol2008/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dispute Resolution by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tabucanon et al.: Tabucanon: Philippine Community Mediation Philippine Community Mediation, Katarungang Pambarangay Gil Marvel P. Tabucanon,*James A. Wall, Jr.,** and Wan Yan*** I. BACKGROUND In a recent article contemplating the challenges society will face to survive the next half century, Joel Cohen surmised that one requisite for survival is find- ing domestic and international institutions to resolve conflicts.' Currently, media- tion appears to be the frontrunner for domestic resolutions. It is applied to a wide variety of conflicts, including labor-management negotiations, community dis- putes, school conflicts, and marital problems. Moreover, there is evidence-from China, Taiwan, India, Britain, Australia, Japan, and Turkey-indicating that med- iation is being utilized worldwide.2 When applied worldwide to a variety of conflicts, mediation assumes diverse forms. -

LOCAL BUDGET MEMORANDUM No, 80

LOCAL BUDGET MEMORANDUM No, 80 Date: May 18, 2020 To : Local Chief Executives, Members of the Local Sanggunian, Local Budget Officers, Local Treasurers, Local Planning and Development Coordinators, Local Accountants, and AU Others Concerned Subject : INDICATIVE FY 2021 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT (IRA) SHARES OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT UNITS (LGUs) AND GUIDELINES ON THE PREPARATION OF THE FY 2021 ANNUAL BUDGETS OF LGUs Wiifl1s3ii 1.1 To inform the LGUs of their indicative IRA shares for FY 2021 based on the certification of the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) on the computation of the share of LGUs from the actual collection of national internal revenue taxes in FY 2018 pursuant to the Local Government Code of 1991 (Republic Act [RA] No. 7160); and 1.2 To prescribe the guidelines on the preparation of the FY 2021 annual budgets of LGUs. 2.0 GUIDELINES 2.1 Allocation of the FY 2021 IRA 2.1.1 In the computation of the IRA allocation of LGUs, the following factors are taken into consideration: 2.1.1J FY 2015 Census of Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay, as approved through Proclamation No. 1269 dated May 19, 2016;1 and 2.1.1,2 FY 2001 Master List of Land Area certified by the Land Management Bureau pursuant to Oversight Committee on Devolution Resolution No, 1, s. 2005 dated September 12, 2005. Declaring as Official the 2015 Population of the Philippines by Province, City/Municipality, and Barangay, Based on the 2015 Census of Population Conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority Page 1 1 2.1.2 The indicative FY 2021 IRA shares of the individual LGUs were computed based on the number of existing LGUs as of December 31, 2019. -

The Barangay Justice System in the Philippines: Is It an Effective Alternative to Improve Access to Justice for Disadvantaged People?

THE BARANGAY JUSTICE SYSTEM IN THE PHILIPPINES: IS IT AN EFFECTIVE ALTERNATIVE TO IMPROVE ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOR DISADVANTAGED PEOPLE? Dissertation for the MA in Governance and Development Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex By Silvia Sanz-Ramos Rojo September 2002 Policy Paper SUMMARY This paper will analyse the Barangay Justice System (BJS) in the Philippines, which is a community mediation programme, whose overarching objective is to deliver speedy, cost-efficient and quality justice through non-adversarial processes. The increasing recognition that this programme has recently acquired is mainly connected with the need to decongest the formal courts, although this paper will attempt to illustrate the positive impact it is having on improving access to justice for all community residents, including the most disadvantaged. Similarly, the paper will focus on link between the institutionalisation of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) and the decentralisation framework in the country. It will discuss how the challenging devolution of powers and responsibilities from the central government to the barangays (village) has facilitated the formal recognition of the BJS as an alternative forum for the resolution of family and community disputes. Moreover, the paper will support the idea that dispute resolution is not autonomous from other social, political and economic components of social systems, and will therefore explore how the BJS actually works within the context of the Philippine society. Thus, the analysis will be based on the differences between how the BJS should work according to the law and how it really operates in practice. It will particularly exhibit the main strengths and limitations of the BJS, and will propose certain recommendations to overcome the operational problems in order to ensure its effectiveness as an alternative to improve access to justice for the poor. -

Rule on Access to Information About the Sandiganbayan

• .\, ABOUT THE SANDIGANBAYAN " :J:. Sandiqanbayan Centennial Building Commonwealth Avenue corner ~ ~ ;".. Batasan Road, Quezon City 1100 • Webslte sb judiciary gov ph • ...• Email: info sb uoiciary ov ph • Telefax 9514582 ~/ ,~ -/ ," "',,1 :\ G \' WHEREAS, pursuant to Section 28, Article 11of the 1987 Constitution, the State adopts and implements a policy of full public disclosure of all its transactions involving public interest, subject to reasonable conditions prescribed by law; WHEREAS, Section 7, Article III of the 1987 Constitution guarantees the right of the people to information on matters of public concern. Access to official records, and documents, and papers pertaining to official acts, transactions, or decisions, as well as to government research data used as basis for policy development, shall be afforded the citizen, subject to such limitations as may be provided by law; WHEREAS, the Judiciary has always maintained the principle of transparency and accountability in the court system, and full disclosure of its affairs pursuant to the aforesaid constitutional provision; WHEREAS, the Supreme Court promulgated resolutions defining the people's right to information, setting forth the extent thereof and explaining its limitations (on account of privilege and confidentiality) regarding matters and concerns affecting the operation of the Judiciary, its officers and employees; WHEREFORE, the Sandiganbayan hereby adopts and promulgates the followingRule on Access to Information: TITLEI .:.Preliminary Matters .:. Section 1. TITLE.- This set of rules shall be known and cited as "The Rule on Access to Information," hereinafter referred to as "Rule." Section 2. PURPOSE. - The Rule seeks to provide the guidelines, processes and procedures by which the Sandiganbayan shall deal with requests for access to information, as defined in this Rule, received pursuant to Section 7, Article III of the 1987 Constitution.