Iran's Involvement with Syrian Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hezbollah's Syrian Quagmire

Hezbollah’s Syrian Quagmire BY MATTHEW LEVITT ezbollah – Lebanon’s Party of God – is many things. It is one of the dominant political parties in Lebanon, as well as a social and religious movement catering first and fore- Hmost (though not exclusively) to Lebanon’s Shi’a community. Hezbollah is also Lebanon’s largest militia, the only one to maintain its weapons and rebrand its armed elements as an “Islamic resistance” in response to the terms of the Taif Accord, which ended Lebanon’s civil war and called for all militias to disarm.1 While the various wings of the group are intended to complement one another, the reality is often messier. In part, that has to do with compartmen- talization of the group’s covert activities. But it is also a factor of the group’s multiple identities – Lebanese, pan-Shi’a, pro-Iranian – and the group’s multiple and sometimes competing goals tied to these different identities. Hezbollah insists that it is Lebanese first, but in fact, it is an organization that always acts out of its self-interests above its purported Lebanese interests. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, Hezbollah also has an “expansive global network” that “is sending money and operatives to carry out terrorist attacks around the world.”2 Over the past few years, a series of events has exposed some of Hezbollah’s covert and militant enterprises in the region and around the world, challenging the group’s standing at home and abroad. Hezbollah operatives have been indicted for the murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri by the UN Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) in The Hague,3 arrested on charges of plotting attacks in Nigeria,4 and convicted on similar charges in Thailand and Cyprus.5 Hezbollah’s criminal enterprises, including drug running and money laundering from South America to Africa to the Middle East, have been targeted by law enforcement and regulatory agen- cies. -

Islam, Models and the Middle East: the New Balance of Power Following the Arab Spring1

Islam, Models and the Middle East: The New Balance of Power following the Arab Spring1 Burhanettin DURAN* and Nuh YILMAZ** Abstract Key Words The Arab Spring has created a fertile Model, Islam, balance of power, Middle ground for the competition of different models East, theo-political, New Sunnism, Arab (Turkish, Iranian and Saudi) and for a new Spring, Salafi, Shia, Wahhabi. balance of power in the Middle East and North Africa. These three models, based on three distinct styles of politics, go hand in hand Introduction with competing particular politics of Islam. Their search for a new order in the region The aim of this article is to discuss the synthesises covert and overt claims for regional changing balance of power in the Middle leadership, national interests and foreign policy priorities. This article argues that the new East and North Africa (MENA) region emerging regional order will be established on following the Arab Spring by focusing either a theo-political understanding, in other on the foreign policies of the four leading words on securitisation and alliances based states- Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and on sectarian polarisation which will lead to Egypt- and their political and religious more interference from non-regional actors, or on a gradual reform process of economic models. The main emphasis will be the integration and diplomatic compromise. In way in which how these four countries the first case, biases and negative perceptions use their models as vehicles to compete will be deepened in reference to history and for supremacy in a new regional order. to differences in religious interpretation, and will result in conflict, animosity and outside Therefore, the problem will not be interference. -

When Maqam Is Reduced to a Place Eyal Sagui Bizawe

When Maqam is Reduced to a Place Eyal Sagui Bizawe In March 1932, a large-scale impressive festival took place at the National Academy of Music in Cairo: the first international Congress of Arab Music, convened by King Fuad I. The reason for holding it was the King’s love of music, and its aim was to present and record various musical traditions from North Africa and the Middle East, to study and research them. Musical delegations from Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Morocco, Algiers, Tunisia and Turkey entered the splendid building on Malika Nazli Street (today Ramses Street) in central Cairo and in between the many performances experts discussed various subjects, such as musical scales, the history of Arab music and its position in relation to Western music and, of course: the maqam (pl. maqamat), the Arab melodic mode. The congress would eventually be remembered, for good reason, as one of the constitutive events in the history of modern Arab music. The Arab world had been experiencing a cultural revival since the 19th century, brought about by reforms introduced under the Ottoman rule and through encounters with Western ideas and technologies. This renaissance, termed Al-Nahda or awakening, was expressed primarily in the renewal of the Arabic language and the incorporation of modern terminology. Newspapers were established—Al-Waq’i’a al-Masriya (Egyptian Affairs), founded under orders of Viceroy and Pasha Mohammad Ali in 1828, followed by Al-Ahram (The Pyramids), first published in 1875 and still in circulation today; theaters were founded and plays written in Arabic; neo-classical and new Arab poetry was written, which deviated from the strict rules of classical poetry; and new literary genres emerged, such as novels and short stories, uncommon in Arab literature until that time. -

From the Iranian Corridor to the Shia Crescent a Hoover, Fabrice Balanche

From the Iranian Corridor to the Shia Crescent A Hoover, Fabrice Balanche To cite this version: A Hoover, Fabrice Balanche. From the Iranian Corridor to the Shia Crescent: Demography and Geopolitics. 2021. halshs-03175780 HAL Id: halshs-03175780 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03175780 Submitted on 21 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License A HOOVER INSTITUTION ESSAY From the Iranian Corridor to the Shia Crescent DEMOGraPhy and GeoPOLitiCS BY FABRICE BALANCHE In December 2004, the king of Jordan asserted his fear of a Shia crescent forming in the Middle East from Iran to Lebanon, what we call the Iranian Corridor.1 Yet many observers and researchers were skeptical about King Abdullah’s assertion.2 On the one hand, the Shiite-Sunni clash was not viewed as a serious component in the dynamics of the Middle East. During the Iran-Iraq war (1980–88), Iraqi Shiites had remained loyal to the Sunni Saddam Hussein and analysts drew the conclusion that the religious divide was no longer relevant. In general, Western analysts are reluctant to see religion or tribalism as important for fear of being accused of “Orientalism,” an accusation popularized by Edward Said and Order International the and Islamism still stifling discussion about the region. -

Sheikh Qassim, the Bahraini Shi'a, and Iran

k o No. 4 • July 2012 o l Between Reform and Revolution: Sheikh Qassim, t the Bahraini Shi’a, and Iran u O By Ali Alfoneh The political stability of the small island state of Bahrain—home to the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet—matters to the n United States. And Sheikh Qassim, who simultaneously leads the Bahraini Shi’a majority’s just struggle for a more r democratic society and acts as an agent of the Islamic Republic of Iran, matters to the future of Bahrain. A survey e of the history of Shi’a activism in Bahrain, including Sheikh Qassim’s political life, shows two tendencies: reform and t revolution. Regardless of Sheikh Qassim’s dual roles and the Shi’a protest movement’s periodic ties to the regime in Tehran, the United States should do its utmost to reconcile the rulers and the ruled in Bahrain by defending the s civil rights of the Bahraini Shi’a. This action would not only conform to the United States’ principle of promoting a democracy and human rights abroad, but also help stabilize Bahrain and the broader Persian Gulf region and under- mine the ability of the regime in Tehran to continue to exploit the sectarian conflict in Bahrain in a way that broadens E its sphere of influence and foments anti-Americanism. e Every Friday, the elderly Ayatollah Isa Ahmad The Sunni ruling elites of Bahrain, however, l Qassim al-Dirazi al-Bahrani, more commonly see Sheikh Qassim not as a reformer but as d known as Sheikh Qassim, climbs the stairs to the a zealous revolutionary serving the Islamic pulpit at the Imam al-Sadiq mosque in Diraz, d Bahrain, to deliver his sermon. -

Iran, Country Information

Iran, Country Information COUNTRY ASSESSMENT - IRAN April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES VA HUMAN RIGHTS - OVERVIEW VB HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VC HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A - CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B - POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C - PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D - REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1. This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2. The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum/human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum/human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3. The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4. It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1. The Islamic Republic of Iran Persia until 1935 lies in western Asia, and is bounded on the north by the file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Iran.htm[10/21/2014 9:57:59 AM] Iran, Country Information Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, by Turkey and Iraq to the west, by the Persian Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman to the south, and by Pakistan and Afghanistan to the east. -

Shia Islamism and Iranian Influence

FACTSHEET Islamism in West Asia-North Africa strengthened relations fell apart after Saddam Hus- Shia Islamism and sein’s fall from power in 2003.2 Iranian Influence Iraq: Rival turned reluctant ally Prepared by Emily Hawley, Research Associate Despite Iraq’s Shia majority, Sunnis dominated the political system through the secular-nationalist In 2006, as Iraq’s Shia majority watched the execu- Ba’athist party for decades championing a rivalry with tion of former President Saddam Hussein, one clear Iran that culminated in a nine-year war in the 1980s. victor emerged from America’s controversial war: Iran. However after Saddam Hussein fell, Iraq experienced Iraq’s transition from Iran’s fierce enemy, to probable a Shia resurgence. Although this development shook ally was a major success for the Islamic Republic and Iran’s foes, Iran-Iraq relations remain complicated. one of the biggest shifts in the regional order of power since Iran’s establishment as an Islamic Republic in There is no doubt that the new government is more 1979. The region’s Sunni leaders watched Iran’s wax- amenable to Iran than Saddam Hussein’s regime, ing power with open concern, leading some to term but with centuries of rivalry and a bloody recent war, Iran’s influence in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon the “Shia Iraq’s people are wary. Iran has built on its pre-exist- crescent.” ing ties with certain Iraqi Shia parties like the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, Dawa, and the Sadrists. But The birth of the Islamic Republic many Iraqis, even Shias, remain wary of their former enemy and are suspicious of Iranian involvement in In 1979, despite Iran having the fifth largest military internal politics.3 in the world and US backing,1 mass opposition over- threw the Shah with little violence. -

Whose Agenda Is Served by the Idea of a Shia Crescent?

Whose Agenda Is Served by the Idea of a Shia Crescent? Amir M. Haji-Yousefi* Abstract After the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, it became evident that Iraq’s Shia majority would dominate the future government if a free election was going to be held. In 2004, Jordan’s King Abdullah, anxiously warned of the prospect of a “Shia crescent” spanning Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. This idea was then picked up by others in the Arab world, especially Egypt’s President Mubarak and some elements within the Saudi government, to reaffirm the Iranian ambitions and portray its threats with regard to the Middle East. This article seeks to unearth the main causes of promoting the idea of a revived Shiism by some Arab countries, and argue that it was basically proposed out of the fear that what the American occupation of Iraq unleashed in the region would drastically change the old Arab order in which Sunni governments were dominant. While Iran downplayed the idea and perceived it as a new American conspiracy, it was grabbed by the Bush administration to intensify its pressures on Iran. It also sought to rally support in the Arab world for US Middle East policy in general, and its failed policy toward Iraq in particular. Thus, to answer the above mentioned question, a close attention would be paid to both the Arab and Iranian agenda in the Middle East after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in order to establish which entities benefit most from the perception of a Shia crescent. The difference between the two main schools of thought in Islam, Shiism and Sunnism, is mainly based on the issue of who should have led Islam after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. -

Chapter 2 Power Structures and Factional Rivalries in the Islamic Republic of Iran | 51

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Iranian political elite, state and society relations, and foreign relations since the Islamic revolution Rakel, E.P. Publication date 2008 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rakel, E. P. (2008). The Iranian political elite, state and society relations, and foreign relations since the Islamic revolution. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Chapter 2 Power Structures and Factional Rivalries in the Islamic Republic of Iran | 51 Chapter 2 Power Structures and Factional Rivalries in the Islamic Republic of Iran 2.1 Introduction The Islamic revolution caused a fundamental change in the composition of the politi- cal elite in Iran, whose secular oriented members were replaced by mainly clergies and religious laypersons. -

Bahrain and the Global Balance of Power After the Arab Spring Lars Erslev Andersen DIIS Working Paper 2012:10 WORKING PAPER

DIIS workingDIIS WORKING PAPER 2012:10paper Bahrain and the global balance of power after the Arab Spring Lars Erslev Andersen DIIS Working Paper 2012:10 WORKING PAPER 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2012:10 LARS ERSLEV ANDERSEN is senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies e-mail: [email protected] DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. DIIS WORKING PAPER 2012:10 © The author and DIIS, Copenhagen 2012 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Layout: Ellen-Marie Bentsen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-501-1 Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk 2 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2012:10 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Introduction 5 The Balance of Power and the Politics of Identity 5 The Case of Bahrain 8 Conclusion 12 References 13 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2012:10 ABSTracT The global balance of power is changing, and the role of the US as the only superpower is being challenged by emerging new powers and a still more powerful China. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Persian Gulf. -

Draft 3-2 Arne's Comment.Pdf (699.7Kb)

1 2 The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Eight departments, associated research institutions and the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine in Oslo. Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments. The Noragric Master thesis are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master programme “International Environmental Studies”, “International Development Studies” and “International Relations”. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric. © Bijan Tafazzoli, August 2014 [email protected] Noragric Department of International Environment and Development Studies P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 64 96 52 00 Fax: +47 64 96 52 01 Internet: http://www.nmbu.no/noragric 3 Declaration I, (Bijan Tafazzoli), declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. Signature……………………………….. Date 15th August 2014 4 Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to thank my wonderful family especially my brother Behrang for all their support and the motivation they gave me over the years. -

Shaabi Shakedown.Pdf

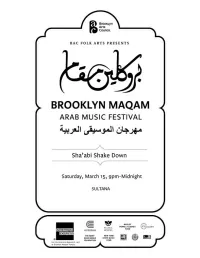

BAC FOLK ARTS PRESENTS BROOKLYN MAQAM ARAB MUSIC FESTIVAL Ahlan wa Sahlan! Welcome to Brooklyn Maqam Arab Music Festival featuring local musicians, bands, and dancers presenting Arab musical traditions from Egypt, Yemen, Israel, Tunisia, Palestine, Iraq, Morocco, Syria, Lebanon, and Sudan. Maqam is the Arabic word referring to the patterns of musical notes, based on a quarter note system, that form the building blocks of traditional Arab music. Join BAC Folk Arts throughout March 2008 for Brooklyn Maqam concerts, symposia, and workshops featuring local musicians specializing in Arab folk traditions, classical forms, and contemporary arrangements. Entry to all events is FREE of charge and all events are open to the public. Saturday, March 15, 9:00pm- midnight Sultana Sha’abi Shake Down Program This evening features 4 vocalists and bands performing diverse styles emanating from Morocco, Tunisia, and of course- Brookyn! Party down to Moroccan and Tunisian popular music traditions such as sha’abi and rai with El Mostafa Jdidi, Salah Rhani, Noureddine, and Reeyad El Tunsi; Jowad Bohsina on org and Hicham on percussion. Then jam with Moroccan Sephadic fusion ensemble Asefa. Salah Rhani and Noureddine Rhani and Noureddine start the night off with sha’abi from their hometown, Casablanca. Rhani treats us to a special performance of violin in the typical Moroccan fashion – held vertically on his knee. The pair will also perform berber (or barbarie) songs of the Atlas mountains, part of the rich musical tradition maintained by the indigenous Berber of North Africa. Nourredine will also introduce the classical tradition of Moroccan song. Salah Rhani: violin, vocals Noureddine: vocals Jowad Bohsina: org Hicham: tabla Reeyad El Tunsi El Tunsi presents a range of popular and folkloric songs known as tunsi, primarily associated with the Tunisia’s capital city, Tunis.