Religion and Composition, 1992-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Advisement Resources Part Ii

RELIGIOUS ADVISEMENT RESOURCES 2020 PART II Notice Regarding External Resources: The listed resources are provided in this document are operated by other government organizations, commercial firms, educational institutions, and private parties. We have no control over the information of these resources which may contain information that could be objectionable or which may not otherwise conform to Department of Defense policies. These listings are offered as a convenience and for informational purposes only. Their inclusion here does not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the Department of Defense of any of the products, services, or opinions of the external providers. The Department of Defense bears no responsibility for the accuracy or the content of these resources. 1 FAITH AND BELIEF SYSTEMS U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Religious Beliefs and Practices http://www.acfsa.org/documents/dietsReligious/FederalGuidelinesInmateReligiousBeliefsandPractices032702.pdf Buddhism Native American Eastern Rite Catholicism Odinism/Asatru Hinduism Protestant Christianity Islam Rastfari Judaism Roman Catholic Christianity Moorish Science Temple of America Sikh Dharma Nation of Islam Wicca U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Religious Literacy Primer https://crcc.usc.edu/files/2015/02/Primer-HighRes.pdf Baha’i Earth-Based Spirituality Buddhism Hinduism Christianity: Anabaptist Humanism Anglican/Episcopal Islam Christian Science Jainism Evangelical Judaism Jehovah’s Witnesses -

Race Resistance October 28–29, 2016 the NITTANY LION INN, UNIVERSITY PARK, PA

Celebrating African American Literature and Language: and racE rEsistancE October 28–29, 2016 THE NITTANY LION INN, UNIVERSITY PARK, PA FEaturEd SpEaKErs Mahogany Kathryn T. John Carmen BROWNE GINES KEENE KYNARD Will Joycelyn Mendi + Keith Mary Helen LANGFORD MOODY OBADIKE WASHINGTON SPONSORS: College of the Liberal Arts, College of the Liberal Arts Undergraduate Studies, the Africana Research Center, Commission on Racial and Ethnic Diversity, the Department of African American Studies, the Department of English, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor Keith Gilyard, the Equal Opportunity Planning Committee, George and Barbara Kelly Professor Aldon Nielsen, Center for American Literary Studies, and Outreach Greetings Greetings one and all! Welcome to Penn State University’s Celebrating African American Literature and Language: Race and Resistance conference. We are honored to have so many scholars, teachers, creative artists, and community activists joining us to celebrate African American Literature and Language, broadly defined. We delight and celebrate this opportunity to come together to share our work, our visions, our questions, and our challenges. This year events is marked by the tensions between a politics of joy and a politics of resistance, and our paper presentations, roundtable discussions, keynotes, and readings will surely explore those tensions as we think collectively about the dynamics of race and resistance in African American literature, language, and arts. We hope that you will find this to be a most memorable event and one that initiates many new conversations. We are especially grateful to our featured speakers, creative writers and artists, and workshop presenters, including Mary Helen Washington, Joycelyn Moody, Mendi + Keith Obadike, Carmen Kynard, Will Langford, Mahogany Browne, Kathryn T. -

Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric Paul Butler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Butler, Paul, "Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 162. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/162 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6679-0_OutOfStyle.ai79-0_OutOfStyle.ai 5/19/085/19/08 2:38:162:38:16 PMPM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K OUT OF STYLE OUT OF STYLE Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric PAUL BUTLER UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-87421-679-0 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-680-6 (e-book) “Style in the Diaspora of Composition Studies” copyright 2007 from Rhetoric Review by Paul Butler. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group, LLC., http:// www. informaworld.com. Manufactured in the United States of America. Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Butler, Paul, Out of style : reanimating stylistic study in composition and rhetoric / Paul Butler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Rhetorics, Poetics, and Cultures: Refiguring College English Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 395 315 CS 215 285 AUTHOR Berlin, James A. TITLE Rhetorics, Poetics, and Cultures: Refiguring College English Studies. Refiguring English Studies Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-4145-5; ISSN-1073-9637 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 218p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 41455-3050: $18.95 members, $25.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College English; *Cultural Context; *Curriculum Evaluation; Educational H:story; *English Departments; *English Instruction; Higher Education; Humanities; Language Role; Literary Criticism; *Rhetoric; Teacher Student Relationship IDENTIFIERS *Critical Literacy; Cultural Studies; Departmental Politics; Literary Canon; Poetics; Postmodernism ABSTRACT . This book, the final work of a noted rhetorician and scholar, examines the history and development of English studies, and the economic and social changes that affect the understanding of the humanities today. Noting that while rhetoric once held a central place in the college curriculum, the book describes how rhetoric became marginalized in college English departments as the study of literature assumed greater status in the 20th century--a result of the shift in decision-making in practical and political matters from the "citizenry" to university-trained experts. The first section of the book provides relevant historical background and explores the political uses of English as a discipline. The second section, "The Postmodern Predicament," shifts the focus to the contemporary scene. The third section, "Students and Teachers," explores the general guidelines recommend3d for the pedagogy of a refigured English studies. -

Improving Religious Literacy: a Contribution to the Debate

All Party Parliamentary Group on Religious Education Improving Religious Literacy: A Contribution to the Debate This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords and has not been approved by either House or its committees. All Party Parliamentary Groups are an informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the group. All Party Parliamentary Group on Religious Education Officers of the All Party Parliamentary Group: Fiona Bruce MP, Chair David Burrowes MP, Vice-Chair Mary Glindon MP, Vice-Chair Lord Singh of Wimbledon, Secretary Aim of the All Party Parliamentary Group: “To provide a medium through which Parliamentarians and organisations with an interest in Religious Education can discuss the current provision of Religious Education, press for continuous improvement, promote public understanding and advocate effective education for every young person in religious world views.” Acknowledgements: The APPG would like to thank respondents to the public consultation, oral witnesses, interviewees and all those who have shown such a keen interest in this inquiry. The APPG would also like to thank Penelope Hanton and Simon Perfect for their work coordinating the inquiry and compiling this report. Improving Religious Literacy: A Contribution to the Debate Foreword 1 Summary of Evidence Contributors 2 1. Aims, Scope and Methodology 3 1.1. Why now? 3 1.2. Methodology and scope 4 2. Towards a Working Definition 6 2.1. A definition 6 3. Religious Education in Schools 8 3.1. Religious Education in England and Wales 8 3.2. -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric LuMing Mao Morris Young Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Mao, LuMing and Young, Morris, "Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 164. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/164 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS REPRESENTATIONS Doing Asian American Rhetoric edited by LUMING MAO AND MORRIS YOUNG UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read Cover art, “All American Girl I” by Susan Sponsler. Used by permission. ISBN: 978-0-87421-724-7 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Representations : doing Asian American rhetoric / edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-87421-724-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) 1. English language--Rhetoric--Study and teaching--Foreign speakers. 2. Asian Americans--Education--Language arts. 3. Asian Americans--Cultural assimilation. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

MISES: Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy Law and Economics ISSN: 2318-0811 ISSN: 2594-9187 Instituto Ludwig von Mises - Brasil Kaesemodel, Gustavo Poletti Self-Ownership and the Libertarian Ethic MISES: Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy Law and Economics, vol. 6, no. 1, 02, 2018, January-March Instituto Ludwig von Mises - Brasil DOI: 10.30800/mises.2018.v6.113 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=586364160002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Disponível em www.misesjournal.org.br MISES: Interdiscip. J. of Philos. Law and Econ, São Paulo, 2018; 6 (1) e-ISSN 2594-9187 Self-Ownership and the Libertarian Ethic Autopropriedade e a Ética Libertária Autopropiedad y la Ética Libertaria Gustavo Poletti Kaesemodel – Centro Universitário Ítalo Brasileiro – [email protected] Palavras-chave: RESUMO Autopropriedade; libertarianismo; ética; O conceito de autopropriedade está intrinsecamente relacionado ao conceito de liberdade individual e é pedra moral; direitos; liberdade fundamental da ética libertária. Em tempos em que as liberdades individuais são constantemente violadas por individual. legislações positivistas, este trabalho tem como objetivo demonstrar os fundamentos da ética libertária, a sua evolução ao longo dos últimos 50 anos e os motivos que a tornam uma ferramenta importante na proteção destes direitos. Analisados os principais conceitos e fundamentos, a ética libertária é colocada à prova das principais críticas que foram feitas ao longo do tempo,ilustrando como elas contribuíram para o seu desenvolvimento e quais pontos ainda não foram completamente explorados ou validados. -

Religious Literacy Quiz Stephen Prothero, Boston University

RELIGIOUS LITERACY QUIZ STEPHEN PROTHERO, BOSTON UNIVERSITY 1. Name the Four Gospels. List as many as you can. 2. Name a sacred text of Hinduism. 3. Name the holy book of Islam. 4. Where, according to the Bible, was Jesus born? 5. George Bush spoke in his first inaugural of the Jericho road. What Bible story was he invoking? 6. What are the first five books of the Hebrew Bible or the Christian Old Testament? 7. What is the Golden Rule? 8. “God helps those who help themselves.” Is this in the Bible? If so, where? 9. “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of God.” Does this appear in the Bible? If so, where? 10. Name the Ten Commandments. List as many as you can. 11. Name the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. 12. What are the seven sacraments of Catholicism? List as many as you can. 13. The First Amendment says two things about religion, each in its own “clause.” What are the two religion clauses of the First Amendment? 14. What is Ramadan? In what religion is it celebrated? 15. Match the Bible characters with the stories in which they appear. (Draw a line from one to the other; some characters may be matched with more than one story or vice versa.) Adam and Eve Exodus Paul Binding of Isaac Moses Olive Branch Noah Garden of Eden Jesus Parting of the Red Sea Abraham Road to Damascus Serpent Garden of Gethsemane RELIGIOUS LITERACY QUIZ (Results) STEPHEN PROTHERO, BOSTON UNIVERSITY Total Students: 122 in 2006; 175 in 2007 Four Gospels: Average=2.3: (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John) 8% said Paul. -

Religious Issues and the Field of English Education Robert Bruce Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2011 Avoiding Engagement with 'Invisibles:' Religious Issues and the Field of English Education Robert Bruce Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Bruce, Robert, "Avoiding Engagement with 'Invisibles:' Religious Issues and the Field of English Education" (2011). All Dissertations. 854. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AVOIDING ENGAGEMENT WITH “INVISIBLES:” RELIGIOUS ISSUES AND THE FIELD OF ENGLISH EDUCATION A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Curriculum and Instruction by Robert Todd Bruce December 2011 Accepted by: Dr. Beatrice Bailey, Committee Chair Dr. Suzanne Rosenblith Dr. Robert Green Dr. Paul Anderson ABSTRACT This study used content analysis of selected documents representing the three dimensions of the field of English Education (curriculum, teacher preparation and development, and research) to ascertain how the field was responding to the larger societal problem that religious intolerance and ignorance pose, especially given the growing religious diversity of American society. Data from the documents were classified into four categories derived from various proposals for the incorporation of religious issues into the public school curriculum: religious literacy, religious concerns related to personal development, religious aspects of multiculturalism, and religious issues related to improved civic engagement. -

RSA14 Schedule Overview Marriott Rivercenter – San Antonio, TX May 22-26, 2014

RSA14 Schedule Overview Marriott Rivercenter – San Antonio, TX May 22-26, 2014 Thursday May 22 8:00-5:00 ARST Preconference 8:00-5:00 ASHR Symposium (Session 1) 8:00-5:00 RSA Career Retreat Friday May 23 8:00-11:00 RSA Board Meeting 8:00-11:00 ASHR Symposium (Session 2) 9:30-12:15 RSA Seminar in cooperation with ISHR (Session 1) (sponsored by Northwestern University) 9:30-10:45 Concurrent Session A 11:00-12:15 Concurrent Session B 12:45-2:00 Concurrent Session C 2:15-4:45 Undergraduate Research Workshops (sponsored by Brigham Young University) 2:15-3:30 Concurrent Session D 3:45-5:00 Concurrent Session E 5:15-6:30 Keynote Address (co-sponsored by University of Denver and Taylor & Francis) 6:30-8:30 Opening Reception (sponsored by Trinity University) Saturday May 24 8:00-9:15 Concurrent Session F 9:30-10:45 Concurrent Session G 11:00-2:00 Research Network (sponsored by Penn State University Press) 11:00-12:15 Concurrent Session H 12:45-2:00 Concurrent Session I 2:15-4:45 RSA Seminar in cooperation with ISHR (Session 2) (sponsored by Northwestern University) 2:15-3:30 Concurrent Session J 3:45-5:00 Concurrent Session K 5:15-6:30 In Conversation Panels 6:30-8:00 Reception (sponsored by University of Kentucky) Sunday May 25 8:00-9:15 Concurrent Session L 9:30-10:45 Concurrent Session M 11:00-12:15 Concurrent Session N 12:30-2:30 RSA Luncheon (sponsored by: The University of Texas, Austin - Department of Communication Studies & Moody College of Communication) 2:45-4:00 Concurrent Session O 4:15-6:15 RSA SuperSessions 6:30-8:30 RSA Graduate -

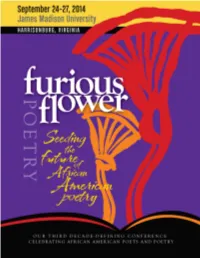

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa.