Housing and Neighborhood Study-Reduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Services Relocate to Crestline Village Second SRO Added

Mountain Brook, Alabama Mountain Brook, the theReporter Reporter Mountain Brook, Ala. www.mtnbrook.org Volume XVIII, Issue 2 MAYORS MESSAGE City Services Relocate to Crestline Village Our new municipal complex is now complete. Our City Hall, Po- U.S. HIGHWAY 280 lice Station and Fire Station #1, which includes the Fire Department Alabama Department of Transpor- administrative offices, have relocated back to Crestline Village. The tation (ALDOT) will move forward as Mountain Brook Chamber of Commerce has also relocated to our new planned with the latest modifications to City Hall. the traffic controls and movements on U.S. Street addresses for our new municipal complex are: Highway 280. City Hall – 56 Church Street Governor Bentley has stated that he sup- Police Department – 101 Tibbett Street ports the modified plan as proposed by AL- Fire Department – 102 Tibbett Street BIRMINGHAM, AL DOT. Resolutions were passed by the State PERMIT NO. 40 U.S. POSTAGE Chamber of Commerce – 101 Hoyt Lane PRSRT STD House of Representatives, the State Sen- We appreciate the patience of the Crestline merchants and residents PAID ate and the City of Mountain Brook. Also, during this construction project. Please come and visit us! Council President Virginia Smith, Council- man Billy Pritchard and I paid a personal visit to the Governor. Untold numbers of Second SRO Added letters and emails, etc. have been sent pro- In efforts to further enhance our relationship with the Mountain testing the modifications and changes to Brook City School System and provide additional security for our Mayor: Lawrence T. Oden the intersection at Cherokee Road and the children, the Mountain Brook Police Department is adding a second CITY COUNCIL intersection at Hampton Inn/Wendy’s and School Resource Officer (SRO). -

High Schools in Alabama Within a 250 Mile Radius of Middle Tennessee State University

High Schools in Alabama within a 250 mile radius of Middle Tennessee State University CEEB High School Name City Zip Code CEEB High School Name City Zip Code 010395 A H Parker High School Birmingham 35204 012560 B B Comer Memorial School Sylacauga 35150 012001 Abundant Life School Northport 35476 012051 Ballard Christian School Auburn 36830 012751 Acts Academy Valley 36854 012050 Beauregard High School Opelika 36804 010010 Addison High School Addison 35540 012343 Belgreen High School Russellville 35653 010017 Akron High School Akron 35441 010035 Benjamin Russell High School Alexander City 35010 011869 Alabama Christian Academy Montgomery 36109 010300 Berry High School Berry 35546 012579 Alabama School For The Blind Talladega 35161 010306 Bessemer Academy Bessemer 35022 012581 Alabama School For The Deaf Talladega 35161 010784 Beth Haven Christian Academy Crossville 35962 010326 Alabama School Of Fine Arts Birmingham 35203 011389 Bethel Baptist School Hartselle 35640 010418 Alabama Youth Ser Chlkvlle Cam Birmingham 35220 012428 Bethel Church School Selma 36701 012510 Albert P Brewer High School Somerville 35670 011503 Bethlehem Baptist Church Sch Hazel Green 35750 010025 Albertville High School Albertville 35950 010445 Beulah High School Valley 36854 010055 Alexandria High School Alexandria 36250 010630 Bibb County High School Centreville 35042 010060 Aliceville High School Aliceville 35442 012114 Bible Methodist Christian Sch Pell City 35125 012625 Amelia L Johnson High School Thomaston 36783 012204 Bible Missionary Academy Pleasant 35127 -

City of Vestavia Hills Planning and Zoning Commission

CITY OF VESTAVIA HILLS PLANNING AND ZONING COMMISSION AGENDA AUGUST 10, 2017 6:00 P.M. Roll Call. Pledge of Allegiance Approval of Minutes: July 13, 2017 Preliminary Plats (1) P-0817-39 Liberty Park Joint Venture, LLP Is Requesting Preliminary Plat Approval For Liberty Park Town Village 6.5 Acre Commercial Subdivision. The Purpose For This Request Is To Add Infrastructure . The Property Is Owned By Liberty Park Joint Venture, LLP and Is Zoned Vestavia Hills PNC. Final Plats (2) Consent Agenda: A. P-0817-38 Wedgeworth Realty, Inc. Is Requesting Final Plat Approval For A Resurvey of Lots 15 & 16, Altadena Park Subdivision. The Purpose For This Request Is To Resurvey Shared Lot Line. The Property Is Owned By Wedgeworth Realty, Inc. and Is Zoned Vestavia Hills R-1. B. P-0817-40 HD Holdings Is Requesting Final Plat Approval For Topfield Resurvey No. 2. The Purpose For This Request Is To Combine Two Parcels And One Lot Into One Larger Lot. The Property Is Owned By HD Holdings and Is Zoned Vestavia Hills O-1. C. P-0817-41 Liberty Park Joint Venture, LLP Is Requesting Final Plat Approval For Heritage Hills-Phase 1 Resurvey No. 6. The Purpose For This Request Is To Add A Storm Drainage Easement. The Property Is Owned By Liberty Park Joint Venture, LLP and Is Zoned Vestavia Hills PR-1. Rezoning/Conditional Use Recommendations: (3) P-0717-35 Continental Equity Corporation & Russell W. Polhemus Is Requesting Rezoning for 2221 & 2301 Old Columbiana Rd. from Vestavia Hills Inst-1 to Vestavia Hills B-2 The Purpose Of A Sports Medicine & Fitness Institute Medicine & Fitness Institute With A Conditional Use For Outdoor Recreation For The Purpose Of Recreation, Fitness, and Sports Training. -

Jefferson County Delinquent Tax List

JEFFERSON COUNTY DELINQUENT TAX LIST BIRMINGHAM DIVISION 020-007.000 003-003.000 ABDULLAH NAEEMAH STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 34 PARCEL-ID: 29-00-19-1- FT TO POB S-26 T-17 W 257.6 FT TH SLY ALG RD TAX NOTICE LOT 67 BLK 7 CLEVELAND POB 82 FT SW OF INTER OF MUN-CODE: 39 INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 29-00-04-1- 016-011.000 SECT TWSP RANGE R-3 R/W 204.3 FT TH E 242.4 THE STATE OF ALABAMA TAX AND COST: $1102.80 SE RW OF 3RD AVE S & E/L PARCEL-ID: 29-00-17-3- ADAMS RAVONNA D 006-009.001 LOT 15 BLK 12 ROSEMONT TAX AND COST: $236.64 SECT TWSP RANGE FT TO POB JEFFERSON COUNTY STORM WATER FEE OF SW 1/4 014-001.000 CLEMENTS LOTS 17 18 & 19 BLK 11 TAX AND COST: $383.91 ALEXANDER TAMMY LYNN TAX AND COST: $162.57 SECT TWSP RANGE INCLUDED SEC 29 TP 17 R 2 TH CONT LOT 16 BLK 2 YEILDING MUN-CODE: 35 HIGHLAND LAKE LAND CO PB STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 01 ALLEN LARRY TAX AND COST: $635.89 UNDER AND BY VIRTUE OF 4729 COURT S SW 25 FT TH SE 140 FT TO & BRITTAIN SURVEY OF PARCEL-ID: 13-00-36-1- 13 PG 94 INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 22-00-04-2- MUN-CODE: 32 STORM WATER FEE A DECREE OF THE PROBATE BIRMINGHAM TRUST ALLEY TH GEORGE W SMITH 005-025.000 TAX AND COST: $3291.53 ALDHABYANI MUTLAQ 000-004.001 PARCEL-ID: 22-00-26-1- INCLUDED COURT OF SAID COUNTY MUN-CODE: 32 NE 25 FT ALG ALLEY TH NW TAX AND COST: $1275.78 LOT 25 BLK 5 STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 37 COM NW COR OF NE 1/4 OF 012-011.000 ALLIANCE WEALTH I WILL, ON THE MAY 22, PARCEL-ID: 29-00-08-2- 140 FT TO POB LYING IN STORM WATER FEE MEADOWBROOK ESTS INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 23-00-11-4- NW 1/4 SEC 4 TP 17S R 3W LOT 3 BLK 1 DRUID -

Fiscal Years 2020-2024

Capital Budget and Capital Improvement Program Fiscal Years 2020-2024 FINANCE DEPARTMENT Lester D. Smith, Jr., Chief Financial Officer Aaron Saxton, Deputy Director Barbara McGrue, Manager of Budget Management Diana Bolden, Budget Officer Florence Fitzgerald, Budget Analyst Quanita Washington, Budget Analyst Derrick Gray, II, Budget Analyst The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to the City of Birmingham, Alabama for its annual budget for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2018. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. MAYOR RANDALL L. WOODFIN CITY COUNCIL VALERIE A. ABBOTT, PRESIDENT, DISTRICT 3 WILLIAM PARKER, PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, DISTRICT 4 CLINTON P. WOODS, DISTRICT 1 HUNTER WILLIAMS, DISTRICT 2 DARRELL O’QUINN, DISTRICT 5 CRYSTAL N. SMITHERMAN, DISTRICT 6 WARDINE ALEXANDER, DISTRICT 7 STEVEN W. HOYT, DISTRICT 8 JOHN R. HILLIARD, DISTRICT 9 DEPARTMENT HEADS AUDITORIUM ..................................................... Faye Oates, Commissioner of Sports and Entertainment CITY CLERK .......................................................................................................... -

Best of Bham 62 Jazz Cat Ball - Supporting Neglected Animals Expertise of St

#abouttownmag APRIL 2016 COMPLIMENTARY best place to bring a first date best Margarita best charity event best girls night out our 1st annual readers’ poll best BBQ B Best of ham best neighborhood bar best sportsbar best new restaurant best late night bar best place to buy wine The Quality and Expertise of St. Vincent’s. April The Convenience of Walk-in Care. B best of ham abouttownsite.com INSIDE 15 Out and About 20 Pointe Ball - Hosted by the Alabama Ballet 22 Elevate the Stage - Benefiting Camp Smile-A-Mile 24 Bags and Brews - Presented by St. Vincent’s Hospital 26 Heart2Heart - Hosted aTeam Ministries 28 Gallery Bar - Grand Opening 30 Phoenix Ball - Supporting the Boys and Girls Clubs 34 G3 300 - Homes Party 36 A Better Way to Spend Valentine’s Day - Supporting Better Basics We offer walk-in care for minor injury and illness, 38 Christopher Showcase - Benefiting Open Hands Overflowing Hearts 40 Orange Theory - Grand Opening ranging from minor cuts that may need stitches to St. Vincent’s One Nineteen 41 Red Nose Ball - 24th Annual 42 Wild About Chocolate - Valentine Gala to coughs and cold. Open after hours and seven 44 A Night Under the Big Top - Presented By Glenwood Jr. Board 45 All Aces - Casino Night days a week, our center provides the quality and 7191 Cahaba Valley Road 47 Best of Bham 62 Jazz Cat Ball - Supporting Neglected Animals expertise of St. Vincent’s with the convenience Hoover, AL 35242 of walk-in care. We provide on-site diagnostics, COVER (205) 408-2366 Hannah Godwin at Bettola in Pepper Place advanced technology, a new state-of-the-art clothes and accessories by Elle in Crestline Village facility, and experienced and compassionate staff Mon.-Fri. -

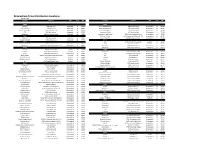

Birmingham Times Distribution Locations (By Zip Code) Location Address City State ZIP Location Address City State ZIP

Birmingham Times Distribution Locations (By Zip code) Location Address City State ZIP Location Address City State ZIP 35020 35209 Chevron 1228 18th St N Bessemer AL 35020 Sam's Mediterranean 932 Oxmoor Road Birmingham AL 35209 Valero 4th Ave 900 4th Ave N Bessemer AL 35020 Magic City Sweet Ice 715 Oak Grove Rd Birmingham AL 35209 Bessemer City Hall 1700 3rd Avenue N Bessemer AL 35020 Seed Coffee House 174 Oxmoor Road Birmingham AL 35209 CVS 901 9th Avenue Bessemer AL 35020 Homewood Diner 162 Oxmoor Road Birmingham AL 35209 Walgreens 1815 9th Avenue North Bessemer AL 35020 Homewood High School 1901 South Lakeshore Drive Birmingham AL 35209 35022 O'Henry's Coffee 569 Brookwood Village, Ste. 101 Birmingham AL 35209 Walmart 750 Academy Dr Bessemer AL 35022 Cocina Superior 587 Brookwood Village Birmingham AL 35209 Carnation Buffet 5020 Academy Ln Bessemer AL 35022 352010 35023 CVS 3300 Clairmont Plaza South Irondale AL 35210 Exxon 14th Street 1401 Carolina Ave Bessemer AL 35023 Shell 5400 Beacon Drive Irondale AL 35210 Walgreens 3025 Allison Bonnett Memorial Hwy Birmingham AL 35023 El Cazador 1540 Montclair Road Birmingham AL 35210 35064 New China 7307 Crestwood Bvd Crestwood AL 35210 Chevron 3640 R Scrushy Blvd Fairfield AL 35064 35211 Jet Pep 7150 Aaron Aranov Dr Fairfield AL 35064 Walgreens 668 Lomb Avenue SW Birmingham AL 35211 Shell 6620 Aaron Aronov Dr Birmingham AL 35064 CVS 632 Tuscaloosa Avenue Birmingham AL 35211 Miles College 5500 Myron Massey Blvd Lunchroom Fairfield AL 35064 BP 641 Lomb Ave Birmingham AL 35211 Fairfield Library -

Polling Sites 2018-List with Contact Info

CITIZEN PARTICIPATION PROGRAM NEIGHBORHOOD ASSOCIATION ELECTION 2018 POLLING SITE LIST Polling Site/Location Neighborhood Associations Voting at This Site Lawson State Community College East Brownsville, West Brownsville, Roosevelt, 3060 Wilson Road SW Grasselli Heights, Hillman, Hillman Park, Industrial Birmingham, Alabama 35221 Center, Tarpley City, West Goldwire, Jones Valley, Geri Albright Mason City, Powderly, Riley-Travellick, Garden Office of Public Relations Highlands, Oxmoor Arthur Shores Fine Arts Building, 925-2515, 929-6315 Gym (Room 255) [email protected] Five Points West Library Belview Heights, Bush Hills, Central Park, Ensley 4812 Avenue W. Ensley Highlands, Fairview, Green Acres, Arlington-West Birmingham, Alabama 35208 End, Germania Park, Oakwood Place, Rising-West Janine Langston, Coordinator Princeton, West End Manor 226-4013 Pratt City Library Ensley, Sherman Heights, Tuxedo, Wylam, Oak 508 Dugan Avenue Ridge, Dolomite, Central Pratt, North Pratt, Sandusky, Birmingham, Alabama 35214 South Pratt Deborah Blackmon, Director 791-4997 North Birmingham Recreation Center Smithfield Estates, Thomas, Acipco-Finley, 3501 28th Street North Collegeville, Fairmont, Harriman Park, Hooper City, Birmingham, Alabama 35207 North Birmingham Shonae Eddins - Bennett, Director, Park & Rec. Bd. 254-2391 Tawayna Jones, Center Director, 322-5251 Legion Field College Hills, East Thomas, Enon Ridge, Graymont, 400 Graymont Avenue West Smithfield, North Titusville, South Titusville, Birmingham, Alabama 35204 Woodland Park Shonae Eddins-Bennett, -

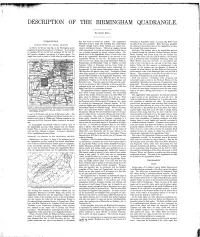

Description of the Birmingham Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE BIRMINGHAM QUADRANGLE. By Charles Butts. INTRODUCTION. that flow across it toward the Atlantic. The Appalachian Tennessee, in Sequatchie Valley, and along Big Wills Creek Mountains occupy a broad belt extending from southwestern are parts of the same peneplain. Below the Coosa peneplain LOCATION, EXTENT, AND GENERAL RELATIONS. Virginia through western North Carolina and eastern Ten the streams of the southern part of the Appalachian province As shown by the key map (fig. 1), the Birmingham quad nessee to northeastern Georgia. This belt is a region of strong have eroded their present channels. rangle lies in the north-central part of Alabama. It is bounded relief, characterized by points and ridges 3000 to 6000 feet or Drainage. The northern part of the Appalachian province by parallels 33° 30' and 34° and meridians 86° 30' and 87° over in height, separated by narrow V-shaped valleys. The is drained through St. Lawrence, Hudson, Delaware, Susque- and contains, therefore, one-quarter of a square degree. Its general level of the Appalachian Valley is much lower than hanna, Potomac, and James rivers into the Atlantic and length from north to south is 34.46 miles, its width from east that of the Appalachian Mountains on the east and of the through Ohio River into the Gulf of Mexico; the southern Appalachian Plateau on the west. Its surface is character part is drained by New, Cumberland, Tennessee, Coosa, and 87 ized by a few main valleys, such as the Cumberland Valley in Black Warrior rivers into the Gulf. In the northern part £35 Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, the East many of the rivers rise on the west side of the Great Appa Tennessee Valley in Tennessee, and -the Coosa Valley in lachian Valley and flow eastward or southeastward to the Alabama, and by many subordinate narrow longitudinal val Atlantic; in the southern part the direction of drainage is leys separated by long, narrow ridges rising in places 1000 to reversed, the rivers rising in the Blue Ridge and flowing west 1500 feet above the general valley level. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

OMB Approval No. 1024—0018 NFS Form 10-900a (Expires Jan. 2005) (Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number Page SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 03001129 Date of Listing: November 17, 2003 Property Name: Woodlawn Historic District County: Jefferson State: Alabama none___________ Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. November 17,2003 Signature of the^Ceeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Section 3. Certification The recommended level of significance is hereby changed to local. Section 8. Significance The period of significance is hereby changed to 1880-1952. The Alabama State Historic Preservation Office was notified of this amendment. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name Woodlawn Historic District other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by 1 st Ave. N.. 47th St. N.. 61 st St. N. and 1-20/59 not for publication N/A city or town Birmingham_________________________________________________ vicinity N/A________ state Alabama code AL county Jefferson___________________ code 073 zip code 35212 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination f"| request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Jefferson County

JEFFERSON COUNTY ADAMSVILLE--See INDEX OF MUNICIPAL LAWS AGRICULTURE Goats running at large, prohibited--1919, 120 Hogs running at large, prohibited--1898, 834; 1900, 2259 AIRPORTS Authority established--(GBLA) 1971, 3935 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Beer, bond by sellers required--1955, 1279 Beer distributors regulated--1971, 1505 Beer, draft beer authorized--(GBLA) 1973, 953 Beer, draft beer in civic center--(GBLA) 1973, 952 Beer, sale distribution areas--1977, 1207 Beer tax--(GBLA) 1951, 1132; 1956, 397; 1959, 233; (GBLA) 1969, 699, 996; 1971, 1505; 1977, 1207 Liquor tax--1959, 1935 Manufacture authorized--(GBLA) 1973, 811 Restaurants, additional sales tax--2001-545, 1097 Sale at Civic Center--(GBLA) 1971, 1104; (GBLA) 1975, 182 Sale of wine, wholesaler and supplier agreements, business relations--2013-346, 1230 Sale on Sunday, referendum--90-177, 198 Sale regulated--1859, 559; 1861, 174; 1862, 156; 1870, 190, 195; 1871, 202; 1872, 173, 176, 185, 187; 1873, 94, 97; 1874, 276; 1882, 489; 1884, 231; 1886, 693; 1888, 258, 417, 870; 1892, 15; 1900, 1943, 2037; 1903, 102; 1907, 425, 749; (GBLA) 1971, 1106 Sales and use tax--1959, 1395; (GBLA) 1965, 533; amended--(GBLA) 79-747, 1323 Unstamped beverages, control--(GBLA) 1961, 1073 Wines, sale of table wine authorized--(GBLA) 1973, 1688; (GBLA) 1977, 1182 ANIMALS Dead animals removal from parks and highways--(GBLA) 1957, 630 Impounded by board of health--(GBLA) 1953, 799 ANNEXATION Municipal tax assessments for newly annexed or newly incorporated territory--(GBLA) 1964, 184 Municipalities, additional -

Community Health Needs Assessment 2019

COMMUNITY HEALTH NEEDS ASSESSMENT 2019 • Mission • Vision • Values • Mission: To provide the highest quality health care in a patient-focused environment in the most cost effective manner Vision: To become a leader in the health care community. Values: Professionalism – We deliver high quality care by being experts in the field. Attitude – We foster a positive and uplifting environment for our patients and each other. Teamwork – We work together to overcome obstacles and achieve success. Integrity – We take pride in upholding the highest standards, both morally and professionally. Excellence – We commit to providing every patient with an exceptional health care experience. Nurturing – We show compassion and give comfort to each and every patient. Trust – We have faith in each other so patients can place confidence in us. 1. • Table of Contents • Executive Summary ................................................................3 Methodology ................................................................4 Community Information ..........................................................5-10 About Medical West .......................................................11 - 15 Comparison Community Information .......................................................16 - 17 2017 BRFSS Data .......................................................18 - 22 2019 County Health Rankings Data .......................................................23 - 25 Community Health Status Indicators Data .......................................................26 - 27