Global Health Governance, Volume IV Issue 2: Spring 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harvard Public Health Review Fall 2008

Harvard Public Health Review Fall 2008 WILL DIGITAL HEALTH RECORDS FIX U.S. HEALTH CARE? INSIDE New HSPH Dean Julio Frenk XDR-TB marches on Health and taxes Surgical checklist Genes and environment Disasters in China and Myanmar Amazing alumni HARVA RD School of Pu blic Health DEAN OF THE FACULTY VISITING COMMITTEE DEAN’S COUNCIL Barry R. Bloom Steven A. Schroeder Gilbert Butler Chair Walter Channing, Jr. Harvard ALUMNI COUNCIL Barrie M. Damson Ruth L. Berkelman Mitchell L. Dong Jo Ivey Boufford The Harvard Public Health Review Officers John H. Foster Louis W. Cabot is published three times a year for Mark S. Clanton, mph ’90 A. Alan Friedberg Nils Daulaire supporters and alumni of the Harvard President C. Boyden Gray Nicholas N. Eberstadt School of Public Health. Its readers share Rajat Gupta Royce Moser, Jr., mph ’65 Cuthberto Garza a commitment to the School’s mission: Julie E. Henry, mph ’91 President-Elect Jo Handelsman advancing the public’s health through Stephen B. Kay Elsbeth Kalenderian, mph ’89 Gary King learning, discovery, and communication. Rachel King Secretary Jeffrey P. Koplan Nancy T. Lukitsh Risa Lavizzo-Mourey Harvard Public Health Review J. Jacques Carter, mph ’83* Beth V. Martignetti Bancroft Littlefield Harvard School of Public Health Immediate Past President David H. M. Matheson Nancy L. Lukitsh Office for Resource Development Richard L. Menschel Vickie M. Mays Third Floor, East Atrium Councilors Ahmed Mohiuddin Michael H. Merson 401 Park Drive 2005-2008 Adeoye Y. Olukotun, Anne Mills Boston, Massachusetts 02215 Bethania Blanco, SM ’73 mph ’83 Kenneth Olden (617) 384-8988 Marise S. -

Vaccine Visions and Their Global Impact

© 1998 Nature Publishing Group http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine COMMENTAR' Barry Bloom (a Howard Hughes Investigator at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and Roy Widdus (Coordinator of the Children's Vaccine Initiative) describe their vision of global implementation of vaccines, highlighting what has already been achieved and, perhaps more importantly, what remains to be done. They also call for further efforts to develop the broad collaborations required to achieve a new vision for global vaccine use. Vaccine visions and their global impact Shortly after the assassination of Prime tain because, as Lewis Thomas noted, we Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984, Jim BARRY R. BLOOM1 tend to take for granted the technologies 2 Grant, Administrator of UNICEF and & ROY WIDDUS that work best2• Hafdan Mahler, Director-General of The third great vision-the eradication World Health Organization (WHO), flew to New Delhi on an of paralytic poliomyelitis-is on the way to being achieved. extraordinary mission. They proposed to her surviving son, Although the scientific problems of creating safe and effective Rajiv, that instead of building a shrine or temple, he honor his polio vaccines were largely overcome by the 1960s, to have mother by making a commitment to immunize all the children global impact, political problems must also be overcome. Few of India against poliomyelitis by the end of the century. On countries want their infectious diseases to be publicly reported, December 6 and 7, 1996, in two National Vaccine Days, 121 and Ciro de Quadros of the Pan American Health Organization million Indian children were vaccinated against polio at came up with a brilliantly imaginative solution to a delicate 650,000 immunization posts by 2.6 million volunteers. -

Defense 2020 “Covid-19 and the U.S. Military”

Center for Strategic and International Studies TRANSCRIPT Defense 2020 “Covid-19 and the U.S. Military” RECORDING DATE Wednesday, April 1, 2020 GUESTS Steve Morrison Senior Vice President, and Director, Global Health Policy Center, CSIS Mark Cancian Senior Advisor, International Security Program, CSIS Christine Wormuth Director, International Security and Defense Policy Center, RAND Corporation Christine Wormuth Director, International Security and Defense Policy Center, RAND Corporation HOST Rear Admiral (Ret.) Tom Cullison Former Deputy Surgeon General of the U.S. Navy, and Adjunct Fellow, Global Health Policy Center, CSIS Transcript by Rev.com Kathleen Hicks: Hi, I'm Kathleen Hicks, Senior Vice President and Director of the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and this is Defense 2020 a CSIS podcast examining critical defense issues in the United States is 2020 election cycle. We bring in defense experts from across the political spectrum to survey the debates over the US military strategy, missions and funding. This podcast is made possible by contributions from BAE systems, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and the Thales Group. Kathleen Hicks: On this episode of Defense 2020, I hosted discussion with four experts on COVID-19 and the US military. Steve Morrison, Senior Vice President and Director of Global Health Policy at CSIS, Mark Cancian, Senior Advisor in the International Security Program at CSIS, Christine Wormuth, Director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center at the RAND Corporation and Rear Admiral (Ret.), Tom Cullison Former Deputy Surgeon General of the US Navy and an Adjunct Fellow in the Global Health Policy Center at CSIS. -

TRINITY COLLEGE Cambridge Trinity College Cambridge College Trinity Annual Record Annual

2016 TRINITY COLLEGE cambridge trinity college cambridge annual record annual record 2016 Trinity College Cambridge Annual Record 2015–2016 Trinity College Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 01223 338400 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.trin.cam.ac.uk Contents 5 Editorial 11 Commemoration 12 Chapel Address 15 The Health of the College 18 The Master’s Response on Behalf of the College 25 Alumni Relations & Development 26 Alumni Relations and Associations 37 Dining Privileges 38 Annual Gatherings 39 Alumni Achievements CONTENTS 44 Donations to the College Library 47 College Activities 48 First & Third Trinity Boat Club 53 Field Clubs 71 Students’ Union and Societies 80 College Choir 83 Features 84 Hermes 86 Inside a Pirate’s Cookbook 93 “… Through a Glass Darkly…” 102 Robert Smith, John Harrison, and a College Clock 109 ‘We need to talk about Erskine’ 117 My time as advisor to the BBC’s War and Peace TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 3 123 Fellows, Staff, and Students 124 The Master and Fellows 139 Appointments and Distinctions 141 In Memoriam 155 A Ninetieth Birthday Speech 158 An Eightieth Birthday Speech 167 College Notes 181 The Register 182 In Memoriam 186 Addresses wanted CONTENTS TRINITY ANNUAL RECORD 2016 | 4 Editorial It is with some trepidation that I step into Boyd Hilton’s shoes and take on the editorship of this journal. He managed the transition to ‘glossy’ with flair and panache. As historian of the College and sometime holder of many of its working offices, he also brought a knowledge of its past and an understanding of its mysteries that I am unable to match. -

Autism and MMR Vaccine Study an 'Elaborate Fraud,' Charges BMJ Deborah Brauser Authors and Disclosures

Autism and MMR Vaccine Study an 'Elaborate Fraud,' Charges BMJ Deborah Brauser Authors and Disclosures January 6, 2011 — BMJ is publishing a series of 3 articles and editorials charging that the study published in The Lancet in 1998 by Andrew Wakefield and colleagues linking the childhood measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine to a "new syndrome" of regressive autism and bowel disease was not just bad science but "an elaborate fraud." According to the first article published in BMJ today by London-based investigative reporter Brian Deer, the study's investigators altered and falsified medical records and facts, misrepresented information to families, and treated the 12 children involved unethically. In addition, Mr. Wakefield accepted consultancy fees from lawyers who were building a lawsuit against vaccine manufacturers, and many of the study participants were referred by an antivaccine organization. In an accompanying editorial, BMJ Editor-in-Chief Fiona Godlee, MD, Deputy BMJ Editor Jane Smith, and Associate BMJ Editor Harvey Marcovitch write that there is no doubt that Mr. Wakefield perpetrated fraud. "A great deal of thought and effort must have gone into drafting the paper to achieve the results he wanted: the discrepancies all led in 1 direction; misreporting was gross." A great deal of thought and effort must have gone into drafting the paper to achieve the results he wanted: the discrepancies all led in 1 direction; misreporting was gross. Although The Lancet published a retraction of the study last year right after the UK General Medical Council (GMC) announced that the investigators acted "dishonestly" and irresponsibly," the BMJ editors Dr. -

Dr Fiona Godlee

QUARTER ONE / 2017 INSIGHT A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION FOR MEMBERS DR FIONA GODLEE DEMENTIA DENTISTRY ON MAKING AN APP FRIENDING DILEMMA Profile of the BMJ editor A new toolkit offers guidance What goes into the Is it ever okay to accept a and campaigning medical on providing dental care to development and testing of a Facebook Friend request from journalist dementia patients medical app? a patient? QUARTER ONE / 2017 Editor Dr Barry Parker 10 12 Managing editor Jim Killgore Associate editor Joanne Curran Editorial departments Medical Dr Richard Brittain Dental Mr Aubrey Craig Legal Simon Dinnick Design and production Connect Communications 19 0131 561 0020 www.connectmedia.cc Printing and distribution L&S Litho Correspondence Insight Editor MDDUS Mackintosh House 120 Blythswood Street Glasgow G2 4EA Photograph: Magda Rakita Photograph: [email protected] 4 MDDUS news 16 Case files QUARTER ONE / 2017 INSIGHT 6 News digest Decade of neglect, Google gaffe, A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION FOR MEMBERS Transgender records, Recurrent cancer, 8 Briefing Out of scope, He said, she said Can we reduce overtreatment? 20 Dilemma 9 Risk Do I accept a “Friend” request from Free will in consent a patient? DR FIONA GODLEE DEMENTIA DENTISTRY ON MAKING AN APP FRIENDING DILEMMA Profile of the BMJ editor A new toolkit offers guidance What goes into the Is it ever okay to accept a and campaigning medical on providing dental care to development and testing of a Facebook Friend request from journalist dementia patients medical app? a patient? 10 The accidental editor 21 Ethics COVER IMAGE Adam Campbell meets Dr Fiona A vice-like grip on virtue Nor any drop to drink, Gail Lemasurier Godlee, the forthright BMJ editor not Screenprint, 1993 afraid to take a stand 22 Addenda Gail studied fine art printmaking at Manchester Book choice: A is for arsenic, 12 Making a medical app Metropolitan University and graduated in 1990. -

United States Policy and Military Strategy in the Middle East

S. HRG. 114–350 UNITED STATES POLICY AND MILITARY STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE EAST HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 24; SEPTEMBER 22; OCTOBER 27, 2015 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:53 Sep 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 C:\USERS\WR47328\DESKTOP\21401.TXT WILDA UNITED STATES POLICY AND MILITARY STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE EAST VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:53 Sep 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\USERS\WR47328\DESKTOP\21401.TXT WILDA S. HRG. 114–350 UNITED STATES POLICY AND MILITARY STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE EAST HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 24; SEPTEMBER 22; OCTOBER 27, 2015 Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–401 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:53 Sep 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\WR47328\DESKTOP\21401.TXT WILDA COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Chairman JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma JACK REED, Rhode Island JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BILL NELSON, Florida ROGER F. -

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT the RECOMMENDED DOSE with RAY MOYNIHAN | Australia.Cochrane.Org/Trd EPISODE 1

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT THE RECOMMENDED DOSE WITH RAY MOYNIHAN | australia.cochrane.org/trd EPISODE 1 - Dr Fiona Godlee, Editor-in-Chief of the BMJ (British Medical Journal) 18 October 2017 Ray Moynihan: Hello, and welcome to The Recommended Dose, a podcast encouraging a more questioning approach to healthcare. Today, it's our great privilege to feature Dr. Fiona Godlee, editor in chief of the British Medical Journal, one of the oldest and most influential journals in the world, which has a reputation for upsetting vested interests. Pushing, for example, for much greater transparency about [00:00:30] the ties between doctors and drug companies, or as Fiona says, stirring up hornets' nests. And as we'll hear, while she leads one of the top doctors' journals on the planet, owned by the British Medical Association, or BMA, she's actually not that keen on visiting doctors herself, unless it's really necessary. Fiona Godlee: I think I'm one of those people who'd rather not take pills if I don't have to, and rather not see doctors if I don't have to, so that's my bias. Ray Moynihan: [00:01:00] Whether you're a hardened researcher, a hard-working student or health professional, someone running a hospital or health system, and especially if you don't work within the world of medicine, I have no doubt you'll love listening to the BMJ's editor in chief, Fiona Godlee, and hear her stirring up a few more hornets' nests. Fiona Godlee: Well thanks Ray, I do see it as a privilege. -

Investing in Our Common Future

Investing in Our Common Future 2 Page 2 Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health Background Paper for the Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health: Investing in Our Common Future Working Papers of the Innovation Working Group - Version 2 Contents Page Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… 5 Tore Godal, Special Adviser to the Prime Minister of Norway on Global Health - Co-Chair, Innovation Working Group, Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health Scott C Ratzan, Vice-President, Global Health, Government Affairs & Policy, Johnson & Johnson - Co-Chair, Innovation Working Group, Global Strategy for Women’s and Children’s Health Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 7 1. Results-Based Financing (RBF) In Service Demand and Delivery ……………………………...……… 11 Health Results Innovation Program Team: Darren Dorkin, Petra Vergeer, Rachel Skolnik and Jen Sturdy of the World Bank 2. The Health Systems Funding Platform ………………………………………………………………….…..…. 15 GAVI Alliance, The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, World Bank and World Health Organization 3. Public-Private Partnership Models …………………………………………………………………….……..... 19 Barry Bloom, Professor of Public Health, Harvard School of Public Health Wendy Woods, Partner and Managing Director, Boston Consulting Group 4. Innovative Use of Mobile Phones and Related Information and Communication Technologies ….... 28 Scott C Ratzan, MD, Vice-President, Global Health, Government Affairs & Policy, Johnson & Johnson Denis Gilhooly, Executive Director, Digital He@lth Initiative, United Nations 5. New and Emerging Medical Technologies ……………………………………………………………..………. 36 Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Program Officers Andrew Serazin and Margaret Cornelius 6. Innovative Technologies for Women’s and Children’s Health ………………………………..………….. 39 Christopher J Elias, MD, MPH, President and CEO, PATH 7. Innovations on The Indian Scene that Relate to Improved Maternal and Newborn Health …..…. -

Whither America? a Strategy for Repairing America’S Political Culture

Whither America? A Strategy for Repairing America’s Political Culture John Raidt Foreword by Ellen O. Tauscher Whither America? A Strategy for Repairing America’s Political Culture Atlantic Council Strategy Paper No. 13 © 2017 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publi- cation may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council 1030 15th Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-1-61977-383-7 Cover art credit: Abraham Lincoln by George Peter Alexander Healy, 1869 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intel- lectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommenda- tions. The Atlantic Council, its partners, and funders do not determine, nor do they necessari- ly endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s particular conclusions. November 2017 Atlantic Council Strategy Papers Editorial Board Executive Editors Mr. Frederick Kempe Dr. Alexander V. Mirtchev Editor-in-Chief Mr. Barry Pavel Managing Editor Dr. Mathew Burrows Table of Contents FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................2 WHITHER AMERICA? ...............................................................................................10 -

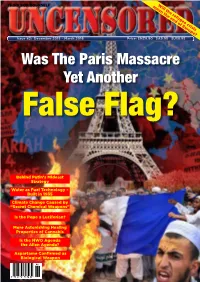

Was the Paris Massacre Yet Another False Flag?

mean Will the the end refugee of Europe? crisis THINK FOR YOURSELF Issue 42: December 2015 – March 2016 Price: $NZ9.90 $A9.95 $US8.95 Was The Paris Massacre Yet Another False Flag? Behind Putin’s Mideast Strategy Water as Fuel Technology – Built in 1935 Climate Change Caused by “Secret Chemical Weapons” Is the Pope a Luciferian? More Astonishing Healing Properties of Cannabis Is the NWO Agenda the Alien Agenda? ALSOAspartame IN THIS ConfirmedISSUE ... as Biological Weapon 42 REALITY GOT YOU DOWN? Issue 1: COLLECTOR’S EDITION “I’d rather have a free bottle in If you start feeling front of me better about yourself, than a prefrontal you’re not thinking. lobotomy.” “Why spend good money on candles, when it’s cheaper to curse the darkness?” A woman’s place is in the home. A man’s place is in a vicious, inhumane, totalitarian corporation. “If it weren’t for pickpockets I’d have no sex life at all.” NOW! WITH EXTRA SARCASM AT NO EXTRA COST!!! Price: $5.95 The Pessimist’s Book of Wisdom By Jonathan Eisen (Editor of Uncensored) Only $10 (includes P/H to NZ and Australia). Please post your order (cheques or credit card details) to: The Full Court Press Ltd. PO Box 44-128, Pt Chevalier, Auckland 1246, NZ “If people in the media cannot de- cide whether they are in the busi- “Instead of the triumph of democracy and progress, we got violence, poverty and social disaster. Nobody cares a bit about ness of reporting news or manu- human rights, including the right to life. -

Key Officials September 1947–July 2021

Department of Defense Key Officials September 1947–July 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Introduction 1 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials 2 II. Secretaries of Defense 5 III. Deputy Secretaries of Defense 11 IV. Secretaries of the Military Departments 17 V. Under Secretaries and Deputy Under Secretaries of Defense 28 Research and Engineering .................................................28 Acquisition and Sustainment ..............................................30 Policy ..................................................................34 Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer ........................................37 Personnel and Readiness ..................................................40 Intelligence and Security ..................................................42 VI. Specified Officials 45 Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation ...................................45 General Counsel of the Department of Defense ..............................47 Inspector General of the Department of Defense .............................48 VII. Assistant Secretaries of Defense 50 Acquisition ..............................................................50 Health Affairs ...........................................................50 Homeland Defense and Global Security .....................................52 Indo-Pacific Security Affairs ...............................................53 International Security Affairs ..............................................54 Legislative Affairs ........................................................56