Algeria Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artabus.Com/Labidi

Your virtual gallery Mohamed Labidi https://www.artabus.com/labidi/ "La Mitidja (Algerie)." Size (HxW) : 50x60 cm Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Landscape / Category : Painting Year : 2005 "Les hauteures d' Alger 01" Size (HxW) : 63x40 cm Framed Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Landscape / Category : Painting Price : Euros 450 Year : 2007 Desc. : It is a district that is located at heights of Algiers, said: Aine-e-Zeboudja "Maisonnettes sur falaise" Size (HxW) : 58x40 cm Framed Style : realism / Tech. : Ink on paper Theme : Landscape / Category : Painting Price : Euros 300 Year : 2006 "Mosqée en petite Kabylie" Size (HxW) : 16x25 cm Framed Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Landscape / Category : Painting Sold Year : 2008 Desc. : Works commissioned for calendar 2009.for society (Farmalliance) "Palmeraie à l'horizon" Size (HxW) : 36x48 cm Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Landscape / Category : Painting Year : 2006 Page 1/95 Your virtual gallery Mohamed Labidi https://www.artabus.com/labidi/ "Structure" Size (HxW) : 33x43 cm Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Still life / Category : Painting Price : Euros 250 Year : 2007 Desc. : When I am in front of the nature I'm still surprised at the realization of God. "Ain Zeboudja." Size (HxW) : 67x45 cm Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Building / Category : Painting Price : Euros 400 Year : 2006 Desc. : Houses located on steep slope.Ain Zeboudja,Alger. "Cyprès sur la baie" Size (HxW) : 30x22 cm Style : realism / Tech. : Watercolour on paper Theme : Building / Category : Painting Year : 2010 Desc. : Watercolor painted from nature, overlooking the port of Algiers. "Vue sur la baie d'Alger" Size (HxW) : 21x32 cm Style : realism / Tech. -

Comparison Between Two Traditional Algerian Houses

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIV-M-1-2020, 2020 HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, 9–12 September 2020, Valencia, Spain TOWARDS A BETTER KNOWLEDGE OF TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL DEVICES: COMPARISON BETWEEN TWO TRADITIONAL ALGERIAN HOUSES A. Racha 1, *, S. Kacher 1 1 Laboratoire Ville, Architecture et Patrimoine (LVAP), Ecole Polytechnique d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme (EPAU), Algiers, Algeria - [email protected], [email protected] Commission II - WG II/8 KEY WORDS: Vernacular architecture, Traditional houses, Environmental devices, Comparative study ABSTRACT: It has been noticed that research is increasingly focused on exploring opportunities to use environmental devices of traditional origin to create more sustainable contemporary buildings. Unfortunately, this "neo-traditional trend" (Abdelsalam et al., 2013) is hindered by the performance of vernacular solutions, which are unable to meet the new needs of contemporary society. Advocates of this ideology believe that this situation is due to a lack of knowledge of these vernacular devices. From this point of view, this paper aims to establish a better knowledge of them for the purpose of improving their performance within contemporary buildings. Thus, it presents a comparison study between the traditional architecture represented by the Algiers Kasbah house and the M’zab valley house in Algeria. The choice of the case studies was made in light of the fact that notwithstanding the very opposite environmental contexts of each case study, they belong to the same typology of traditional houses called "house with wast ed dar". In fact, they share several similar environmental features such as the patio and the terrace. -

P3 2.E$S Layout 1

WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2015 LOCAL Fugitives, one sentenced to life, arrested in Jahra KUWAIT: Jahra detectives arrested three persons wanted on multiple charges. They include Bader K, Syrian and sen- tenced to five years in jail, Mutlaq A, Kuwaiti and sentenced to five years, and Hussein K, Bedoon (stateless) and sen- tenced to 90 years in jail, or life in prison. The third suspect was arrested inside his house during a police raid. The three were sent to concerned authorities. Gas station burglar caught Meanwhile, Mubarak Al-Kabeer detectives arrested a Kuwaiti man accused of committing a robbery at a gas sta- tion in Adan earlier. The suspect reportedly drove a car that did not carry any license plates. The suspect works for the same company that owns the station he robbed, the Interior Ministry said in a statement. He was sent to con- cerned authorities. Traffic campaign Separately, Hawally police carried out a traffic campaign that resulted in issuing 580 tickets, impounding 55 cars and arresting three persons on different charges. The Adan gas station robbery suspect. The suspects Bader K, Mutlaq A and Hussein K pictured in these handout photos. Crime Report KDF demands releasing detained activists By A Saleh being investigated by the interior ministry. In a statement KMA issued after a doctor KUWAIT: Kuwait Democratic Forum’s (KDF) was accused of causing the death of a Secretary General Bandar Al-Khairan called female citizen he operated on, KMA for issuing a pardon to all those who had Secretary General Dr Mohammed Al-Qenae been prosecuted during a period when stressed that reports about the woman’s “political situations were not favorable”. -

Gulf Affairs

Autumn 2016 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Identity & Culture in the 21st Century Gulf Featuring H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali Minister of Culture and Sports State of Qatar H.E. Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa President Bahrain Authority for Culture & Antiquities Ali Al-Youha Secretary General Kuwait National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters Nada Al Hassan Chief of Arab States Unit UNESCO Foreword by Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Partnerships: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Jamie Etheridge Chief Copy Editor: Jack Hoover Arabic Content Lead: Lolwah Al-Khater Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Communications Manager: Aisha Fakhroo Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Research Assistant: Matthew Greene Copyright © 2016 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2016 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College, or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication. -

To View Online Click Here

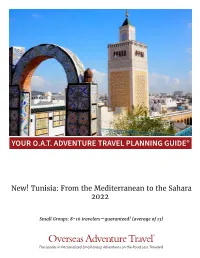

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. New! Tunisia: From the Mediterranean to the Sahara itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Venture out to the Tataouine villages of Chenini and Ksar Hedada. In Chenini, your small group will interact with locals and explore the series of rock and mud-brick houses that are seemingly etched into the honey-hued hills. After sitting down for lunch in a local restaurant, you’ll experience Ksar Hedada, where you’ll continue your people-to-people discoveries as you visit a local market and meet local residents. You’ll also meet with a local activist at a coffee shop in Tunis’ main medina to discuss social issues facing their community. You’ll get a personal perspective on these issues that only a local can offer. The way we see it, you’ve come a long way to experience the true culture—not some fairytale version of it. So we keep our groups small, with only 8-16 travelers (average 13) to ensure that your encounters with local people are as intimate and authentic as possible. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

Sharjah Art Foundation Announces the Late Okwui Enwezor As Curator of Sharjah Biennial 15

For Immediate Release 4 November 2019 Hoor Al Qasimi (left). Photo: Sebastian Böttcher; Okwui Enwezor (right). Photo: Chika Okeke-Agulu Sharjah Art Foundation Announces the Late Okwui Enwezor as Curator of Sharjah Biennial 15 Foundation Director Hoor Al Qasimi to Co-Curate Alongside Working Group Members Tarek Abou El Fetouh, Ute Meta Bauer, Salah M. Hassan and Chika Okeke-Agulu, with the Support of an Advisory Committee Including David Adjaye, John Akomfrah and Christine Tohme SB15 Opens March 2021 in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF) in Sharjah, UAE, today announced the renowned critic and curator Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019) as curator of the next Sharjah Biennial, opening in March 2021. Enwezor conceived the 15th edition of the Sharjah Biennial (SB15), entitled Thinking Historically in the Present, as a platform to reflect on the past fourteen editions of the Biennial and to consider the future of the biennial model. In accordance with Enwezor’s wishes, SB15 will be realized with the support of Sharjah Art Foundation Director Hoor Al Qasimi as co-curator alongside a working group of Enwezor’s longtime collaborators: curator Tarek Abou El Fetouh; professor and Founding Director of NTU CCA Singapore Ute Meta Bauer; art historian and Cornell University professor Salah M. Hassan; and art historian and Princeton University professor Chika Okeke-Agulu. Al Qasimi and the SB15 Working Group will oversee the development and implementation of Enwezor’s curatorial concept in collaboration with an advisory committee composed of architect Sir David Adjaye, artist John Akomfrah and Ashkal Alwan Director Christine Tohme, who will provide additional consultation on the Biennial. -

Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism Author(S): Zeynep Çelik Source: Assemblage, No

Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism Author(s): Zeynep Çelik Source: Assemblage, No. 17 (Apr., 1992), pp. 58-77 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3171225 . Accessed: 12/09/2014 12:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Assemblage. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Fri, 12 Sep 2014 12:01:28 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Zeynep (elik Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism Zeynepgelik is AssociateProfessor of Le Corbusier'sfascination with Islamicarchitecture and ur- Architectureat the NewJersey Institute banism formsa continuing threadthroughout his lengthy of Technology.She is the authorof The career.The first, powerfulmanifestation of this lifelong in- Remakingof lstanbul(University of terest is recordedin his 1911 travelnotes and sketchesfrom Press, and Washington 1986) Displaying the "Orient"- an ambiguousplace, loosely alludingin theOrient: Architecture of Islamat nineteenth- and earlytwentieth-century discourse -

An Inside Look Into Hygiene Education Facilities Completed

COUNTRY: IRAQ Report: March-June 2013 Category: Water and Sanitation Hygiene (WASH)/Sustainability/Hygiene Education/Culture http://www.jen-npo.org/en/contribute Hygiene Education training sessions, and have expressed their admiration and satisfaction of JEN’s work and materials. We would like to thank all our supporters who have made our education programs possible in schools throughout Iraq. WASH Facilities Completed: School Gives Thanks Diala Province’s Om Salma Intermediate School for Girls restroom facilities have been refurbished. Previously the school’s facilities were in unusable and unsanitary conditions. Without proper functioning restrooms, the school could not operate functionally. The headmaster of the girl’s school had previously gone to the Iraqi Department of Education numerous times Above: Girls at the Om Sama Intermediate School listen intently to the requesting repairs, but to no avail, they denied their lectures on proper hygiene and care. requests. JEN received permission from both the Department and Ministry of Education to fund and An Inside Look into Hygiene Education perform the renovations themselves. With dedication and hard work, the new bathrooms have been completed Our hygiene programs, teaching proper practices to and the school is now completely operational. JEN students, have started this March. Security has proven conducted student and teacher trainings about hygiene to be difficult, with many road blockages, especially in education, as well as how to keep their newly the Anbar and Diala provinces, JEN hygiene promoters refurbished restroom clean to ensure its longevity. and engineers cannot always reach our partner schools. School administrators gave their thanks in addition to a The ten-year anniversary of the US-led invasion took surprise song and dance for JEN staff performed by the place on March 19th, where over 60 people were killed in schoolgirls. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.29311/mas.v13i3.333 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Ajana, B. (2015). Branding, legitimation and the power of museums: The case of the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Museum and Society, 13(3), 322-341. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v13i3.333 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Celebrating Manama the Arab Capital of Culture in 2012 the Ministry Of

Celebrating Manama the Arab Capital of Culture in 2012 The Ministry of Culture in the Kingdom of Bahrain in coordination with The Arab Administrative Development Organization-ARADO LEAGUE OF ARAB STATES The 2nd Forum on Festivals in the Arab Countries Diplomat Radisson Hotel, Manama, March 1st &2nd, 2012 OVERVIEW The Second Forum on Festivals in the Arab Countries is the only state-level Arab Festival event hosted in the Arab region. With a galaxy of experts in various fields and masters of great wisdom, this Festival Forum is another highlight of the festivals in the Arab countries. In its second version, this festival forum is organized by the Ministry of Culture in the Kingdom of Bahrain, in coordination with the Arab Administrative Development Organization , to celebrate Manama, the Arab Capital Culture of 2012. This forum is committing itself to both innovation and originality as successfully held in its first version in Beirut in December 2009. Over two days, a bunch of festival presidents, organizers, managers, and art directors will gather to exchange information and expertise about different issues of festivals exploring the way to improve and upgrade the levels of festivals in the Arab countries. The sessions of this forum are comprised into a welcome/opening address, two keynote sessions, and five regular sessions presenting and debating the latest thinking and festival business insights in addition to reviewing the key achievements and challenges facing festivals nowadays. Also, there will be a further focus on the most important issues in the festival industry, plus extended and expanded networking opportunities for neighboring countries to share knowledge and update the quality of their festivals to include all the family. -

Planum II-2011 Di Martino Mapping Communities and Social Problems In

www.planum.net - The Journal of Urbanism Mapping communities and social problems in Jerusalem. Demographic trends, neighbourhood identities and clashing narratives. Claudia De Martino 1 by Planum, Ottobre 2011 II Semester 2011, ISSN 1723-0993 1 Claudia De Martino é ricercatrice presso UNIMED, Unione delle Università del Mediterraneo e dottoranda in Storia Sociale del Mediterraneo all'Università Ca' Foscari di Venezia. Jerusalem is neither holy nor ordinary city. It is difficult to understand how such a contested space, where different legitimizations and narratives are continuously involved and at odds with each other, might be rhetorically assumed as a symbol of peace and coexistence. To all visitors coming first to the city it is clearly visible that Jerusalem is neither heaven on earth nor any especially spiritual place, where all of a sudden human historical or philosophical dilemma will set at rest and find an answer. On the contrary, most probably visitors might walk out of the city more confused and wretched than they stepped in. Exploring the Old City and all its monumental alleys, full of history and diverging memories, foreigners, tourists or whatever the goal of the journey, will come up with the feeling that human beings are complex creatures, difficult to understand in-depth, while even more difficult is to grasp the hidden and ideal motivations of their actions. I would like therefore to introduce my short paper by three of the theoretical premises around which it is built: the first is that Jerusalem is exploiting a collective