Principles of Navigation| Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Europe Is Agog for Beards

Lifestyle FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2014 Metrosexuals be gone: Europe is agog for beards akub Marczewski grew a beard six years ago because he was too lazy to shave. Now he finds himself in the middle of a Jglobal trend. The 21-year-old got his hair and beard trimmed at a new shop with a hip retro vibe, the Barberian Academy & Barber Shop, which opened in Warsaw last month to serve the growing number of Polish men with facial hair. A revival in the cul- ture of barbering in this Eastern European capital is just one sign of how popular beards have become, with actors, athletes and hipsters leading the way. Metrosexuals be gone: Europe is agog for beards. “Worldwide, we are at the height of facial hair,” said Allan Peterkin, a Toronto psychiatrist and author of “One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair.” “It’s a delightful expression of masculinity, people have more respect,” said Salvador Chanza, a 31-year-old but not a super-macho master barber from Spain who trains professionals. Sporting both expression.” After World a handlebar moustache and a substantial beard, he said the War II, men were mostly embrace of facial hair reflected a rejection of the previous clean- clean-shaven, reflecting a shaven metrosexual ethos. military ethos that came to Now facial hair is hugely popular across Western Europe, espe- dominate corporate life, cially in fashion-conscious Paris. And across the globe, it’s the Peterkin said. Over the next month of “Movember” - when men are encouraged to grow a decades facial hair was mustache to raise awareness and funds for men’s health issues. -

The Humanitarians FINISHED DRAFT Script

THE HUMANITARIANS Contact Edwin Thompson: www.bustersfarm.com [email protected] FADE IN. EXT. AFRICA - SERENGETI PLAINS - NIGHT The landscape glows green from night vision goggles. Brush thicket to the left, open plains ahead and right. Sounds of exotic animals, fabric rustling, someone walking on dirt ground. An arm wearing a wrist altimeter reaches to an on/off switch, a gloved finger flips switch to on, pushes start button. Sound of engine idling, revs increase. Running toward open plains. Sounds of breathing, footsteps, and engine. Lifting off of the ground... flying now. The ground gets further away. Silhouette of a woman flying with powered paraglider, gaining altitude. Below, aerial view of plains, herds of animals move slowly, dreamlike. Above, velvet sky is dotted with thousands of stars. Swooping to treetop level, buzzing animals at watering hole, they scatter. Large ranch house compound comes into view, enclosed by a high wall. Gloved finger turns switch to off. Engine stops. Sound of wind. Gliding above the compound. Below, large dogs look up, turning in circles, confused by what they hear. Steaks fall to the ground. Dogs run to steaks. Circling the house, aiming to backside of a hedge row. Ground approaches fast... 20 feet... 10 feet... 5 feet -- FLARE sail. A perfect landing. Sound of harnesses releasing. EXT. GENERAL NKWATCHA’S COMPOUND - NIGHT Silhouette of woman walking crouched, toward the house. Looking around, dogs lie motionless. Silhouette sprinting toward house, disappears behind bushes. Looking in bedroom window, a man is asleep on the bed. INT. GENERAL NKWACHA’S HOUSE - BEDROOM - NIGHT Through the green glow of goggles, a large room, eclectic mix of African and West Indies furniture. -

Ambassador Robert G. Neumann

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR ROBERT G. NEUMANN Recollections Out Of My Life Written in Kabul, Afghanistan April, 1968 Copyright 2015 ADST INTRODUCTION The reflections and reminiscences which follow are not designed to constitute in anyway a complete autobiography. There appears to be no need for such a work, and it would be presumptuous of me to endeavor anything of the kind. And yet, as I have started into the second century of my life, it seems to me that thus far my life has known considerable drama and has touched in one way or another on a number of interesting events. It has certainly been far from dull. In historic terms it saw its beginning in the dying days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, covered deep economic depression and political upheaval including two brief but violent civil wars interspersed with brief periods of imprisonment, and then coming to a violent climax in a much longer period of incarceration and mortal danger. And then, after miraculous deliverance, began the second phase of my life, my emigration to America, with resumption of my studies, marriage and family, but also war and a professional career which eventually elevated the once penniless immigrant boy to the dignity of an ambassador of the United States of America. As these lines are written, their purpose is not clear to me, but because my life has covered so many events and spanned so many varied and different periods and experiences, I felt impelled to record them from memory and to put down some of the thoughts and emotions which passed through my mind as these events took place. -

U2's Triumphant Return · Day of the Dead

PAGE 14 THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY FEATURES November 7, 2000 U2's Triumphant Return Leave Behind Recalls Band's Best Recordings With All That You Can't Leave Behind, and quality becomes obvious as soon as U2 has produced their most highly Bono's crooning voice seeps through your acclaimed record since masterpieces such speakers. This is one gem on the album that should not be overlooked. Continuing Album Review as 1987's Joshua Tree and 1991's on the l ight~r side, "Wild Honey" shows an by Parijat Didolkar Achtung Baby. influence of the simple melodies alongside Bono, the Edge, Larry Mullen Jr. and Adam an acoustic backing that characterized the Clayton have been making music for two '60s with groups such as the Monkees and decades now and still find their best work later, Tom Petty. to be rooted in simplistic feeling rather than "Peace On Earth" has the most heartfelt complex production. Bringing back Brian lyrics on the album. Bono still believes in Eno, among others, they have re~aptured making a better world even if it is only a honesty in their music more than any sound hopeless plea. He sings, ....... Hope and his genre. Although Bono's voice is a little tory won't rhyme/So what's it worth/This weaker and thinner, it still retains its peace on earth." The next track, "When I unmistakable quality to move people that Look At the World," is similar to "Kite" in other vocalists such as Fred Durst or Rob that it would not work for anyone other Thomas have never come close to. -

Jack's Bight : Solace of an Open Place

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-17-1994 Jack's Bight : Solace of an Open Place Hamish Winthrop Ziegler Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Ziegler, Hamish Winthrop, "Jack's Bight : Solace of an Open Place" (1994). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 4440. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/4440 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida JACK'S BIGHT: SOLACE OF AN OPEN PLACE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS by Hamish Winthrop Ziegler 1994 To: Dean Arthur W. Herriott College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Hamish Winthrop Ziegler, and entitled, Jack's Biaht: Solace of an Open Place, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgement. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Campbell McGrath Adele Newson Lyijrhe Barrett, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 17, 1994 The thesis of Hamish Winthrop Ziegler is approved. Dean»Arthur W. Herriott Collage of Arts and Sciences Dr.' Richard L. Campbell Dean of Graduate Studies Florida International University, 1994 ii I dedicate this thesis to my mother, Ann Williams McLean. -

Baron Munchhausen and the Syndrome Which Bears His Name: History of an Endearing Personage and of a Strange Mental Disorder

Baron Munchhausen and the syndrom which bears his name, Vesalius, VIII, 1, 53 - 57, 2002 Baron Munchhausen and the Syndrome Which Bears His Name: History of an Endearing Personage and of a Strange Mental Disorder R. Olry Summary Munchausen syndrome, a mental disorder, was named in 1951 by Richard Asher after Karl Fried rich Hieronymus, Baron Munchhausen (1720-1797), whose name had become proverbial as the nar- rator of false and ridiculously exaggerated exploits. The first edition of Munchausen's tales ap- peared anonymously in 1785 (Baron Munchausen's narrative of his marvellous travels and cam- paigns in Russia), and was wrongly attributed to the German poet Gottfried August Burger who actually edited the first German version the following year. The real author, Rudolph Erich Raspe, never claimed his rights over the successive editions of this book. This paper reviews the extraor- dinary personality of Baron Munchhausen, and the circumstances which led Rudolph Erich Raspe, Gottfried August Burger, and Richard Asher to pay homage to this very endearing personage. Résumé Le syndrome de Munchausen est un trouble psychologique ainsi baptisé en 1951 par Richard Asher, en hommage à Karl Friedrich Hieronymus, baron de Munchhausen (1720-1779), qui s'était rendu célèbre parla narration de ses exploits extravagants. La première édition des aventures de Munch- hausen apparu anonymement en 1785 (Baron Munchausen's narrative ofhis marvellous travels and campaigns in Russia), et fut attribuée à tort au poète allemand Gottfried August Bûrger, celui qui en réalité édita la première traduction allemande l'année suivante. Le véritable auteur, Rudolph Erich Raspe, ne réclama jamais ses droits sur les éditions successives de ce livre. -

Montage Song Suggestions

MONTAGE SONG LIST INTRODUCTION MONTAGE SONGS Song Artist Angels Lullaby Richard Marx A Kiss To Build A Dream On Louis Armstrong As Time Goes By Jimmy Durante Beautiful In My Eyes Joshua Kadison Beautiful Baby Bing Crosby Beautiful Boy Elton John Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Billionaire Travis McCoy Boys Keep Swinging David Bowie Brighter Than The Sun Colbie Caillat Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bubbly Colbie Butterfly Fly Away Miley Cyrus Can You Feel The Love Tonight Elton John Circle Of Life Elton John Count on Me Bruno Mars Everything I Do, I Do It For You Brian Adams Fireflies Owl City First Time I Ever Saw Your Face Celine Dion First Time I Ever Saw Your Face Roberta Flack Flying Without Wings Ruben Studdard God Must Have Spent A Little More Time NSYNC Grenade Bruno Mars Hero Mariah Carey Hey, Soul Sister Train I Am Your Child Barry Manilow I Don’t Wanna Miss A Thing Aerosmith I Hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack I Learned From You Miley Cyrus In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel If I Could Ray Charles Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Lean on Me Glee Let Them Be Little Lonestar Mad World Adam Lambert No Boundaries Kris Allen Ordinary Miracles Amy Sky She’s The One Rubbie Williams Smile Glee The Only Exception Paramore Through The Years Kenny Rogers Times Of Your Life Paul Anka Tiny Dancer Elton John Smile Uncle Kracker U Smile Justin Beiber What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong What A Wonderful World Israel Kamakawiwo'ole Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler You Are So Beautiful Joe Cocker MIDDLE MONTAGE SONGS Song Artist Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Diana Ross Allstar Smashmouth Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet American Girl Tom Petty Angel Lionel Richie Animal Neon Trees Beat Of My Heart Hilary Duf Beautiful Day U2 Beautiful Girl Sean Kingston Billionaire Travis McCoy Born To Be Wild Steppenwolf Bottle It Up Sara Bareilles Break Out Miley Cyrus California Gurls Katy Perry Cooler Than Me Mike Posner Daddys Girl Miley Cyrus Dominoe Jessie J. -

Customer Taster

Published by Lazy Bee Scripts Customer Taster Death and Waxes A Moustache Murder Mystery by Barry Wood A serial killer who steals the moustaches from his victims is at large. Convinced she knows where the killer will strike next, Freya Yorke, a young criminology student, takes a job at an Edinburgh hotel that is hosting the International Moustache Championships. During the evening, Freya is proved right, and there follows a farcical murder investigation into the group of misfits who comprise the competitors and their partners. COPYRIGHT REGULATIONS This murder mystery is protected under the Copyright laws of the British Commonwealth of Nations and all countries of the Universal Copyright Conventions. All rights, including Stage, Motion Picture, Video, Radio, Television, Public Reading, and Translations into Foreign Languages, are strictly reserved. No part of this publication may lawfully be transmitted, stored in a retrieval system, or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, manuscript, typescript, recording, including video, or otherwise, without prior consent of Lazy Bee Scripts. A licence, obtainable only from Lazy Bee Scripts, must be acquired for every public or private performance of a script published by Lazy Bee Scripts and the appropriate royalty paid. If extra performances are arranged after a licence has already been issued, it is essential that Lazy Bee Scripts are informed immediately and the appropriate royalty paid, whereupon an amended licence will be issued. The availability of this script does not imply that it is automatically available for private or public performance, and Lazy Bee Scripts reserve the right to refuse to issue a licence to perform, for whatever reason. -

1 Herakleios' Handlebar: Contextualizing a Change in Imperial

1 Herakleios’ Handlebar: Contextualizing a Change in Imperial Imagery Joel DowlingSoka A paper presented on November 3, 2012 at the Byzantine Studies Conference In 629 CE, the Emperor Herakleios, finally at peace after decades of war with Khusrow II, grew out his beard. Where he had previously worn a close cut beard, his new whiskers were significantly more imposing.1 They reached down to the middle of his chest and were topped by a handlebar moustache that seems to have been helped along with a good deal of wax. This appearance of the emperor is idiosyncratic for a Roman ruler, to say the least, and represents a dramatic departure from the previous centuries of imperial representation. However, scholarly analysis of Heraclius’ post-629 imperial image has mostly ignored the potential ramifications of this change. There have been a few explanations that focus on a new tendency in the seventh century towards portraiture on coinage. For example, Phillip Grierson, in Byzantine Coins, suggested that the image was either Herakleios reverting to a more youthful hairstyle that he had worn before he became emperor or that the hair had grown out on campaign and he “preferred it that way.2 Taking an almost polar opposite position, Walter Kaegi read the new appearance on the coinage as “reflecting aging and fatigue.”3 This latter description may be accurate enough, Herakleios was getting older, but why did he choose to show the entire empire his age with an image so different from prior Roman images? None of the explanations explain why Herakleios would decide to change his appearance in such a revolutionary way. -

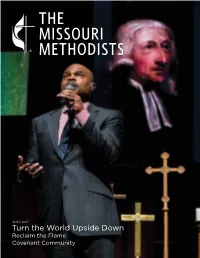

Turn the World Upside Down Reclaim the Flame Covenant Community LETTER from the EDITOR

JULY 2017 Turn the World Upside Down Reclaim the Flame Covenant Community LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Fun at Conference y advice to United Methodist men going When I first braided my beard, a friend asked M to Annual Conference in 2018: stop if I could get away with looking like that at shaving this fall. By next June you should work. I scoffed, and explained that United have enough facial hair for beard braids and a Methodists are very accepting people. I could handlebar moustache. It’s a great ice-breaker get a large neck tattoo, and would probably get for your fellow Methodist friends whom you bonus points on my performance appraisal for haven’t seen in a while. taking a bold initiative to connect with people Fred Koenig, Editor You can use the No-Shave November outside the church walls. (Movember) movement that raises awareness of So Annual Conference was a lot of fun for men’s health issues as an excuse to get started, me. But you don’t really have to do strange Published by then just continue not shaving. I find it pretty things to your facial hair. Annual Conference The Missouri Conference of easy to make a practice of not doing something. looked like it was fun for everyone, from the the United Reactions to my braids varied. Southeast people who had to plan and run the whole Methodist Church 3601 Amron Court District Superintendent Fred Leist asked if my thing, to the first timers who just showed Columbia, MO 65202 braids were some variation on being Hasidic. -

KITE in the S K Y Ian Inglis

14 KITE IN THE S K Y Ian Inglis I was born in the mid-1970s and grew from childhood into adolescence and adulthood to the accompaniment of all the unruly music of the next twenty years – heavy metal, punk, new wave, disco, reggae, grunge. I bought lots of records and, over time, changed from a mere purchaser into an enthusiastic collector. Only of vinyl. Music on vinyl has a texture, a sound of its own, quite different from the clinical perfection of a CD. I concentrate on what I think of as the classic acts from the 1990s. No boy bands, or Britpop, or rap, or female divas like Celine Dion and Mariah Carey, but what I regard as quality rock – REM, Clay Lake, the Red Hot Chilli Peppers, the Smashing Pumpkins, U2. Most of all, Clay Lake. And I’ve always felt that the band’s finest album is The Green. Oh yes, there’s Earthquake Blues and Hidden Places, but The Green’s subtle transition from folk-rock to rock, its eclectic mix of musical perspectives, and its thoughtful, often obscure, lyrical intensity have given me more enjoyment over the years than any other album. Even now, more than three decades after its release, I never tire of hearing it. I’m as familiar with it as I am with the contours of my own face. Work had been getting me down for some time and in the spring, after yet another argument with the new boss, I was fired. I wasn’t sorry to be leaving 1 and I decided to take an early holiday and revisit some of the places in the south that I’d known in younger, happier days. -

Atalacha00chat.Pdf

n I npulfarAXaHtli^ IDYLS &'PlRST JS^^TIG^rOH. Lom>o:T. 1817. ATALAi BY yi. DE ClIATEAUDRIAKT. INDIAN COTTAGE BY J. II. B. SAINT-PI£RUF,. IDYLS; FIRST NAVIGATOR BY SOLOMON GESSxNLR. LONDON: Prill. J for Walker and Edwards; F. C. and J. Rivingtou ; J. Nunn; Cadell and Da- vics ; Longman, IIur»t, Rees, Orme, and Brown ; J. Richardson; Law and Whittaker ; Newni.tu and Co. ; Lackington and Co. ; Black, Parbury, anfl Allen; J. Black and Son; Sherwood, Ntely, and Jones; R. Scholey; IJaUlwin, Cradock, aiitl Joy; Gule aud Tenuer ; J. Robinson ; and li. lit) uoids. 1U17. AT ALA BY M. DE CHATEAl BRIANT: WITH EXPLANATORV ^;OT£i. Pity melts iht Kmi to \o\t."—Dr>jden. PREFACE TRANSLATOR. Monsieur de Chateaubriant, llie inge- nious author of Alala, was led In a curiosity, jialural to ^outli, to visit I/Oui>iana, a country no very new, and so entirely different from any he had seen in Europe. In 1789 he went to North America. " In the midst of deserts, Hnder the huts of savas^es," says he, " was Alala written. I do not know wlielher the public will like this story, which differs so much from all others, and describes manners and customs quite foreign to our own. To give this work the most antique form, I have divided it into Prologue, Becitation, and Epilogue. The prin- cipal parCs of the narration 1 have denominated The Huntsmen, The. Husbandmen, <Sc. in imi- tation of the rbapsodists, who, in the time of primitive Greece, sung fragments of Homer, Buder different titles.