Dangerous Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

To View a Few Sample Pages of 30 Days to Better Jazz Guitar Comping

You will also find that you sometimes need to make big jumps across the neck to keep bass lines going. Keeping a solid bass line is more important than smooth voice leading. For example it’s more important to keep a bass line constantly going using simple chords rather than trying to find the hippest chords you know Day 24: Comping with Bass Lines After learning how to use a bass line with chords in the bossa nova, today’s lesson is about how to comp with bass lines in a more traditional jazz setting. Background on Comping with Bass Lines An essential comping technique that every guitarist learns at some point is to comp with bass lines. The two most important ingredients to this comping style are the feel and the bass line. As Joe Pass says “A good bass line must be able to stand by itself”, meaning that you add the chords where you can. Like many other subjects in this book, bass lines could fill up an entire book of their own, but this section will teach you the fundamental principles such as how to construct a bass line and apply it over the ii-V-I progression. What Chords Should I Use? As with bossa nova comping, it’s best to use simple voicings that are easy to grab to keep the bass line flowing as smoothly as possible. The chord diagram below shows the chords that are going to be used, notice that these are all simple inversions with no extensions, but they give the ear enough information to recognize the chord type and have roots on the bottom two strings. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

The Devil's Interval by Jerry Tachoir

Sound Enhanced Hear the music example in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site at www.pas.org The Devil’s Interval BY JERRY TACHOIR he natural progression from consonance to dissonance and ii7 chords. In other words, Dm7 to G7 can now be A-flat m7 to resolution helps make music interesting and satisfying. G7, and both can resolve to either a C or a G-flat. Using the TMusic would be extremely bland without the use of disso- other dominant chord, D-flat (with the basic ii7 to V7 of A-flat nance. Imagine a world of parallel thirds and sixths and no dis- m7 to D-flat 7), we can substitute the other relative ii7 chord, sonance/resolution. creating the progression Dm7 to D-flat 7 which, again, can re- The prime interval requiring resolution is the tritone—an solve to either a C or a G-flat. augmented 4th or diminished 5th. Known in the early church Here are all the possibilities (Note: enharmonic spellings as the “Devil’s interval,” tritones were actually prohibited in of- were used to simplify the spelling of some chords—e.g., B in- ficial church music. Imagine Bach’s struggle to take music stead of C-flat): through its normal progression of tonic, subdominant, domi- nant, and back to tonic without the use of this interval. Dm7 G7 C Dm7 G7 Gb The tritone is the characteristic interval of all dominant bw chords, created by the “guide tones,” or the 3rd and 7th. The 4 ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ tritone interval can be resolved in two types of contrary motion: &4˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ bbw one in which both notes move in by half steps, and one in which ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ b w both notes move out by half steps. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

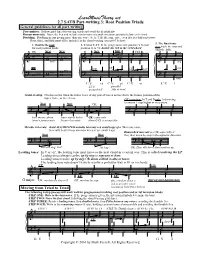

Root Position Triads Part-Writing

LearnMusicTheory.net 2.7 SATB Part-writing 3: Root Position Triads General guidelines for all part-writing Prerequisites. Follow guidelines for voicing triads and avoid the fiendish five. Roman numerals: Name the key and include roman numerals with inversion symbols below each chord. Doubling: Doubling means giving more than one voice (S, A, T, B) the same note, even if it is a different octave. Root, third, and fifth must all be included in the chord voicing (except #3 below). 3. The final tonic 1. Double the root 2. V-vi or V-VI: In the progression root position V to root may triple the root and for root position triads. position vi or VI, double the 3rd in the vi/VI chord. omit the fifth. OK NO! NO! NO! NO! YES 3rd! root root 5th! 3rd! 3rd LT! LT LT 3rd! root 5th! 3rd! root root C:V vi C:V vi C:V vi C:V I LT is parallel unresolved! 5ths & 8ves! Avoid overlap. Overlap occurs when the lower voice of any pair of voices moves above the former position of the upper voice, or vice-versa. OK exception: In T and B only, 3rd moving to unison 1 step higher or vice-versa NO! NO! OK bass moves above tenor moves below OK: same note tenor's former note former bass note (here C-C) is acceptable Melodic intervals: Avoid AUGMENTED melodic intervals and avoid leaps of a 7th in one voice. Generally best to keep common tones or use small leaps. Diminished intervals are OK, especially if NO! NO! they then move by step in the opposite direction. -

Finally a Simple Chord Book Copy

INTRODUCTION Hi, my name is Henry Olsen, and I’ve been teaching guitar professionally for the last three years! After a while, I got tired of showing people the “standard” way of reading chords and seeing them get totally overwhelmed with confusion. I decided it was time I put an end to this madness and develop an easy-to-read, clear, and simple chord book for beginners and advanced players to learn and look up new chords in. &BTZUPSFBE "MMUIFJNQPSUBOUDIPSET In the frst section of the book, I have included open chords 3FBMHVJUBSFYBNQMFT that any beginner guitarist needs to know in order to play all their favorite songs without any difcult barre chords! In the second section, I’ve added variations to those chords that make them sound a bit more colorful. These chords will come in very handy, and you will see them in TONS of modern songs. In the last section, I’ll be teaching you how to take just one chord and turn it into 12 chords just by sliding it up and down the neck of the guitar. I’ve watched many of my private students have a HUGE “ah-ha!” moment using this system, and I can’t wait to share it with you! My goal is to make the simplest and easiest to understand chord book you’ll ever fnd. Please send me an email at [email protected] telling me what you think. I would love to hear from you! 01 SuperSimpleGuitar.org How To Use This Book I´ve set up the book with pictures of a REAL guitar and me playing the chords. -

Figured-Bass Notation

MU 182: Theory II R. Vigil FIGURED-BASS NOTATION General In common-practice tonal music, chords are generally understood in two different ways. On the one hand, they can be seen as triadic structures emanating from a generative root . In this system, a root-position triad is understood as the "ideal" or "original" form, and other forms are understood as inversions , where the root has been placed above one of the other chord tones. This approach emphasizes the structural similarity of chords that share a common root (a first- inversion C major triad and a root-position C major triad are both C major triads). This type of thinking is represented analytically in the practice of applying Roman numerals to various chords within a given key - all chords with allegiance to the same Roman numeral are understood to be related, regardless of inversion and voicing, texture, etc. On the other hand, chords can be understood as vertical arrangements of tones above a given bass . This system is not based on a judgment as to the primacy of any particular chordal arrangement over another. Rather, it is simply a descriptive mechanism, for identifying what notes are present in addition to the bass. In this regime, chords are described in terms of the simplest possible arrangement of those notes as intervals above the bass. The intervals are represented as Arabic numerals (figures), and the resulting nomenclatural system is known as figured bass . Terminological Distinctions Between Roman Numeral Versus Figured Bass Approaches When dealing with Roman numerals, everything is understood in relation to the root; therefore, the components of a triad are the root, the third, and the fifth. -

Fully-Diminished Seventh Chords Introduction

Lesson PPP: Fully-Diminished Seventh Chords Introduction: In Lesson 6 we looked at the diminished leading-tone triad: vii o. There, we discussed why the tritone between the root and fifth of the chord requires special attention. The chord usually appears in first inversion precisely to avoid that dissonant interval sounding against the bass when vii o is in root position. Example 1: As Example 1 demonstrates, placing the chord in first inversion ensures that the upper voices are consonant with the bass. The diminished fifth is between the alto and soprano, concealed within the upper voices. In this case, it is best understood as a resultant interval formed as a result of avoiding dissonances involving the bass. Adding a diatonic seventh to a diminished leading-tone triad in minor will result in the following sonority: Example 2: becomes This chord consists of a diminished triad with a diminished seventh added above the root. It is therefore referred to as a fully-diminished seventh chord. In this lesson, we will discuss the construction of fully-diminished seventh chords in major and minor keys. As you will see, the chord consists of two interlocking tritones, which require particularly careful treatment because of their strong voice-leading tendencies. We will consider its various common functions and will touch on several advanced uses of the chord as well. Construction: Fully-diminished leading-tone seventh chords can be built in major or minor keys. In Roman numeral analyses, they are indicated with a degree sign followed by seventh-chord figured bass numerals, o7 o 6 o 4 o 4 depending on inversion ( , 5 , 3 , or 2 ). -

Augmented Sixth Chords Are Predominant Chords, Meaning They Are Used to Approach Dominant Chords

Augmentedmusic Sixth theory for musicians Chords and normal people by toby w. rush like that moment of incredible tension just before the hero finally kisses the leading lady, the half-step is the go-to interval for creating tension in music of the common ˙ practice period. it drives the entire style! ˙ if one half-step can create such strong tension, how about two half-steps sounding simultaneously? Let’s get creative here for a minute to find a cool new way to approach a diatonic chord. in this case, we’ll use them to approach the dominant triad. ...and approach that first, we’ll start with octave with a half step the doubled root of a below the top note, V chord... #˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & b ˙ ˙ & b ˙ ˙ V & ˙ V ...and, finally, add the V ...and a half step above tonic as the third note. the bottom note... the result is a new chord, one we call the augmented sixth chord, after the interval created by the top and bottom notes. augmented sixth chords are predominant chords, meaning they are used to approach dominant chords. if we just use they are usually used to approach dominant triads, three notes not dominant sevenths, because of the doubled and double the roots present in dominant triads. tonic, we get the #w italian ww however, they also often augmented sixth. b w & approach tonic chords & #˙ ˙ It.6 in second inversion, ˙ ˙ which also contain a doubled fifth scale degree. ? b˙ n˙ b ˙ ˙ if we add the 6 Ger.6 I4 second scale degree instead ˙ ˙ rarely, augmented sixth chords of doubling the # w & ˙ ˙ are found transposed down tonic, we get the ww a perfect fifth, analyzed as french b w ˙ ˙ “on flat two,” and used to augmented sixth. -

Part-Writing Rules.FH9

Important Rules for 4-Part Progressions In general, some theorists (including Ottman and myself) try to spend most of our time telling you what to do rather than what not to do. If you internalize all of our little procedures then you should be able to churn out progressions quickly and easily without really worrying about making mistakes. However, there are times when you really have to be familiar with the rules. Ottman sprinkles many of these around the later chapters of the text, and he tries to summarize everything you need to know in his Appendix A. Ive produced my own summary because I have a few slightly different ideas of what needs emphasis or de-emphasis. Please compare what I say here to what Ottman says. Making each triad Doubling the root. For triads in root position, try to cover all three chord tones in your upper voices. That means you will end up doubling the root. all three tones present doubled root Doubling any other tone in a root-position Ottman (p. 95) teaches that sometimes at triad will happen occasionally, but it is cadences you will end up tripling the root (and considered less good. I will sometimes subtract leaving out the fifth.) Use this for cadences a point for these bad doublings. only. (If you do it in the middle of a progression it will probably cause bad parallels afterwards.) LESS GOOD doubled doubled 3rd 5th tripled root IVI ©2004 Dave Smey. Reproduction and classroom use freely permitted. Using proper spacing (open position) Adjacent upper voices are not allowed to be more than an octave apart.