Assessing Bill Clinton's Legacy: How Will History Remember Him? Panel I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Message

President’s Message his is perhaps the most exciting academic year ever on Hofstra’s campus, as we prepare to host the third and final presidential debate of the 2008 Telection season on October 15, and again present Educate ’08, our unprecedented series of lectures, conferences, exhibitions and events focused on the presidency, history, politics and social issues. For the fall Educate ’08 series, we host nationally known figures such as Robert Rubin and Paul O’Neill, George Stephanopoulos, Dee Dee Myers and Ari Fleischer, Mario Cuomo and the Council on Foreign Relations’ Richard Haass, and many other scholars, journalists and policymakers. The Center for Civic Engagement presents its sixth Day of Dialogue, with nearly 50 sessions on critical issues of the day for Democracy in Performance, a live performance featuring actors portraying historic figures. Many of our academic departments and centers, such as the Peter S. Kalikow Center for the Study of the American Presidency, the National Center for Suburban Studies, and Hofstra Entertainment, will also present events with a presidential theme. The Hofstra Cultural Center’s popular Joseph G. Astman International Concert Series features All American Music, while the Hofstra Cultural Center joins the Hofstra University Museum in presenting a reunion of the directors of Hofstra’s series of renowned presidential conferences for On the Record: A Hofstra Presidential Conference Retrospective. In addition to our exciting political series, the Hofstra Cultural Center and the academic departments continue to present a variety of lectures, concerts, dramatic performances and events that will engage and delight the entire Hofstra and surrounding communities. -

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics Liam Edward Shaffer Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Political History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Shaffer, Liam Edward, "The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 236. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/236 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Parallax View: How Conspiracy Theories and Belief in Conspiracy Shape American Politics Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Liam Edward Shaffer Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements To Simon Gilhooley, thank you for your insight and perspective, for providing me the latitude to pursue the project I envisioned, for guiding me back when I would wander, for keeping me centered in an evolving work and through a chaotic time. -

United States of America Assassination

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD *** PUBLIC HEARING Federal Building 1100 Commerce Room 7A23 Dallas, Texas Friday, November 18, 1994 The above-entitled proceedings commenced, pursuant to notice, at 10:00 a.m., John R. Tunheim, chairman, presiding. PRESENT FOR ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD: JOHN R. TUNHEIM, Chairman HENRY F. GRAFF, Member KERMIT L. HALL, Member WILLIAM L. JOYCE, Member ANNA K. NELSON, Member DAVID G. MARWELL, Executive Director WITNESSES: JIM MARRS DAVID J. MURRAH ADELE E.U. EDISEN GARY MACK ROBERT VERNON THOMAS WILSON WALLACE MILAM BEVERLY OLIVER MASSEGEE STEVE OSBORN PHILIP TenBRINK JOHN McLAUGHLIN GARY L. AGUILAR HAL VERB THOMAS MEROS LAWRENCE SUTHERLAND JOSEPH BACKES MARTIN SHACKELFORD ROY SCHAEFFER 2 KENNETH SMITH 3 P R O C E E D I N G S [10:05 a.m.] CHAIRMAN TUNHEIM: Good morning everyone, and welcome everyone to this public hearing held today in Dallas by the Assassination Records Review Board. The Review Board is an independent Federal agency that was established by Congress for a very important purpose, to identify and secure all the materials and documentation regarding the assassination of President John Kennedy and its aftermath. The purpose is to provide to the American public a complete record of this national tragedy, a record that is fully accessible to anyone who wishes to go see it. The members of the Review Board, which is a part-time citizen panel, were nominated by President Clinton and confirmed by the United States Senate. I am John Tunheim, Chair of the Board, I am also the Chief Deputy Attorney General from Minnesota. -

Geopolitics, Oil Law Reform, and Commodity Market Expectations

OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 63 WINTER 2011 NUMBER 2 GEOPOLITICS, OIL LAW REFORM, AND COMMODITY MARKET EXPECTATIONS ROBERT BEJESKY * Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................... ........... 193 II. Geopolitics and Market Equilibrium . .............. 197 III. Historical U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East ................ 202 IV. Enter OPEC ..................................... ......... 210 V. Oil Industry Reform Planning for Iraq . ............... 215 VI. Occupation Announcements and Economics . ........... 228 VII. Iraq’s 2007 Oil and Gas Bill . .............. 237 VIII. Oil Price Surges . ............ 249 IX. Strategic Interests in Afghanistan . ................ 265 X. Conclusion ...................................... ......... 273 I. Introduction The 1973 oil supply shock elevated OPEC to world attention and ensconced it in the general consciousness as a confederacy that is potentially * M.A. Political Science (Michigan), M.A. Applied Economics (Michigan), LL.M. International Law (Georgetown). The author has taught international law courses for Cooley Law School and the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, American Government and Constitutional Law courses for Alma College, and business law courses at Central Michigan University and the University of Miami. 193 194 OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 63:193 antithetical to global energy needs. From 1986 until mid-1999, prices generally fluctuated within a $10 to $20 per barrel band, but alarms sounded when market prices started hovering above $30. 1 In July 2001, Senator Arlen Specter addressed the Senate regarding the need to confront OPEC and urged President Bush to file an International Court of Justice case against the organization, on the basis that perceived antitrust violations were a breach of “general principles of law.” 2 Prices dipped initially, but began a precipitous rise in mid-March 2002. -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Prominent Political Consultant and Former U.S. Senator Serve As Sanders Scholars

Headlines Prominent political consultant and former U.S. senator serve as Sanders Scholars wo renowned individuals joined the promote the administration’s agenda. He was later appointed U.S. ambassador TUniversity of Georgia School of Law fac- Currently, Begala serves as Research to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. ulty as Carl E. Sanders Political Leadership Professor of Government at Georgetown Among the numerous recognitions he Scholars this academic year – Paul E. Begala, University and is also a political analyst and has received are: the Federal Bureau of political contributor on CNN’s “The commentator for CNN, where he previously Investigation’s highest civilian honor, the Situation Room” and former counselor to co-hosted “Crossfire.” Jefferson Cup; selection as the Most Effective President Bill Clinton, and former U.S. Sen. While on campus, Begala also delivered Legislator by the Southern Governors’ Wyche Fowler Jr. a speech to the university community titled Association; and the Central Intelligence During the fall semester, Begala taught “Politics 2008: Serious Business or Show Agency “Seal” medallion for dedicated ser- Law and Policy, Politics and the Press, while Business for Ugly People?” vice. Fowler is teaching a course on the U.S. Currently, Fowler is Named for Georgia’s 74th governor and Congress and the Constitution this spring. engaged in an interna- 1948 Georgia Law alumnus, Carl E. Sanders, As a former top-rank- tional business and law the Sanders Chair in Political Leadership was ing White House official, practice and serves as created to give law students the opportunity political consultant, cor- chair of the board of the to learn from individuals who have distin- porate communications Middle East Institute, a guished themselves in politics or other forms strategist and university nonprofit research foun- of public service. -

23Rd Annual Legislative Forum October 4, 2018 Legislative Forum 2018

GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS RIGHT TIME. RIGHT PLACE. RIGHT SOLUTION. 23RD ANNUAL LEGISLATIVE FORUM OCTOBER 4, 2018 LEGISLATIVE FORUM 2018 Maine could make national headlines this November because of the number of key races on the ballot this year. With important seats up for grabs and two political parties looking to score “big wins” in our state, the only thing we can predict about our political forecast is that it is unpredictable. • Who will be Maine’s next Governor? • Which party will take control of the State Legislature? • Will incumbents prevail in Maine’s first and second Congressional districts? • Who will win the race for U.S. Senate, and will the result impact the balance of power in Washington? With so much up in the air here in Maine and a stagnant climate looming over Washington, our Legislative Forum’s key note speaker, CNN commentator Paul Begala, will offer his unique perspective and insight on today’s political landscape. He will discuss why Maine’s races will be closely watched and talk about the impact the 2018 midterm elections will have on our country and state. Begala will also offer his thoughts on the biggest issues facing Congress and how the election will impact Washington’s agenda. We’ll also bring to the stage radio power duo Ken and Matt from WGAN Newsradio’s Ken & Matt Show to share their political humor and insights with our Forum guests. Through their comedic banter, they will give “their take” on today’s top policy issues and the candidates running for office. And to close out the day, Maine Credit Union League President/CEO Todd Mason will interview a Special Guest to talk about why credit union advocacy and electing pro-credit union candidates matter. -

The Origins and Impact of Environmental Conflict Ideas

STRATEGIC SCARCITY: THE ORIGINS AND IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONFLICT IDEAS Elizabeth Hartmann Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Submitted for the degree of PhD 2002 1 UMI Number: U615457 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615457 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 rM£ S£S F 20 ABSTRACT Strategic Scarcity: The Origins and Impact of Environmental Conflict Ideas Elizabeth Hartmann This thesis examines the origins and impact of environmental conflict ideas. It focuses on the work of Canadian political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon, whose model of environmental conflict achieved considerable prominence in U.S. foreign policy circles in the 1990s. The thesis argues that this success was due in part to widely shared neo-Malthusian assumptions about the Third World, and to the support of private foundations and policymakers with a strategic interest in promoting these views. It analyzes how population control became an important feature of American foreign policy and environmentalism in the post-World War Two period. It then describes the role of the "degradation narrative" — the belief that population pressures and poverty precipitate environmental degradation, migration, and violent conflict — in the development of the environment and security field. -

Table of Contents

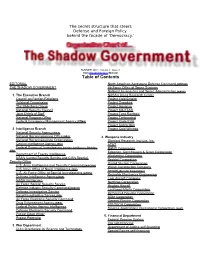

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

Saudi Arabia: Current Issues and U.S

Order Code IB93113 Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Saudi Arabia: Current Issues and U.S. Relations Updated May 24, 2002 Alfred B. Prados Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS Current Issues Security in the Gulf Region Containment Policies toward Iraq U.S. Troop Presence Bombings of U.S. Military Facilities Response to September 11 Terrorist Attacks Arab-Israeli Conflict Crown Prince Abdullah’s Peace Initiative Arms Transfers to Saudi Arabia U.S. Arms Sales Trade Relationships Problems in Commercial Transactions Oil Production Foreign Investment Human Rights, Democracy, and Other Issues Background to U.S.-Saudi Relations Political Development Saudi Leadership Royal Succession Economy and Aid Economic Conditions Aid Relationships Defense and Security Congressional Interest in Saudi Arabia Arms Sales Arab Boycott Trade Practices IB93113 05-24-02 Saudi Arabia: Current Issues and U.S. Relations SUMMARY Saudi Arabia, a monarchy ruled by the rity commitment to Saudi Arabia. Saudi Ara- Saudi dynasty, enjoys special importance in bia was a key member of the allied coalition the international community because of its that expelled Iraqi forces from Kuwait in unique association with the Islamic religion 1991, and approximately 5,000 U.S. troops and its oil wealth. Since the establishment of remain in the country. Saudi Arabia continues the modern Saudi kingdom in 1932, it has to host U.S. aircraft enforcing the no-fly zone benefitted from a stable political system based over southern Iraq; however, Saudi Arabia has on a smooth process of succession to the not offered the use of its territory for major air throne and an increasingly prosperous econ- strikes against Iraq in response to Iraqi ob- omy dominated by the oil sector.