Mcdonald's Case History, 2006–2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donna Lee Brien Writing About Food: Significance, Opportunities And

Donna Lee Brien Writing about Food: Significance, opportunities and professional identities Abstract: Food writing, including for cookbooks and in travel and food memoirs, makes up a significant, and increasing, proportion of the books written, published, sold and read each year in Australia and other parts of the English-speaking world. Food writing also comprises a similarly significant, and growing, proportion of the magazine, newspaper and journal articles, Internet weblogs and other non-fiction texts written, published, sold and read in English. Furthermore, food writers currently are producing much of the concept design, content and spin-off product that is driving the expansion of the already popular and profitable food-related television programming sector. Despite this high visibility in the marketplace, and while food and other culinary-related scholarship are growing in reputation and respectability in the academy, this considerable part of the contemporary writing and publishing industry has, to date, attracted little serious study. Moreover, internationally, the emergent subject area of food writing is more often located either in Food History and Gastronomy programs or as a component of practical culinary skills courses than in Writing or Publishing programs. This paper will, therefore, investigate the potential of food writing as a viable component of Writing courses. This will include a preliminary investigation of the field and current trends in food writing and publishing, as well as the various academic, vocational and professional opportunities and pathways such study opens up for both the students and teachers of such courses. Keywords: Food Writing – Professional Food Writers – Creative and Professional Writing Courses – Teaching Creative and Professional Writing Biographical note Associate Professor Donna Lee Brien is Head of the School of Arts and Creative Enterprise at Central Queensland University, and President of the AAWP. -

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 >> CLICK BELOW TO JUMP TO SECTION DISCOUNTER/ APPAREL BEAUTY SUPPLIES DOLLAR STORE OFFICE SUPPLIES SPORTING GOODS SUPERMARKET/ ACTIVE BEVERAGES DRUGSTORE PET/FARM GROCERY/ SPORTSWEAR HYPERMARKET CHILDREN’S BOOKS ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANT BAKERY/BAGELS/ FINANCIAL FAMILY CARDS/GIFTS BREAKFAST/CAFE/ SERVICES DONUTS MEN’S CELLULAR HEALTH/ COFFEE/TEA FITNESS/NUTRITION SHOES CONSIGNMENT/ HOME RELATED FAST FOOD PAWN/THRIFT SPECIALTY CONSUMER FURNITURE/ FOOD/BEVERAGE ELECTRONICS FURNISHINGS SPECIALTY CONVENIENCE STORE/ FAMILY WOMEN’S GAS STATIONS HARDWARE CRAFTS/HOBBIES/ AUTOMOTIVE JEWELRY WITH LIQUOR TOYS BEAUTY SALONS/ DEPARTMENT MISCELLANEOUS SPAS STORE RETAIL 2 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 APPAREL: ACTIVE SPORTSWEAR 2016 2017 CURRENT PROJECTED PROJECTED MINMUM MAXIMUM RETAILER STORES STORES IN STORES IN SQUARE SQUARE SUMMARY OF EXPANSION 12 MONTHS 12 MONTHS FEET FEET Athleta 46 23 46 4,000 5,000 Nationally Bikini Village 51 2 4 1,400 1,600 Nationally Billabong 29 5 10 2,500 3,500 West Body & beach 10 1 2 1,300 1,800 Nationally Champs Sports 536 1 2 2,500 5,400 Nationally Change of Scandinavia 15 1 2 1,200 1,800 Nationally City Gear 130 15 15 4,000 5,000 Midwest, South D-TOX.com 7 2 4 1,200 1,700 Nationally Empire 8 2 4 8,000 10,000 Nationally Everything But Water 72 2 4 1,000 5,000 Nationally Free People 86 1 2 2,500 3,000 Nationally Fresh Produce Sportswear 37 5 10 2,000 3,000 CA -

Tangy Temptation: Mcdonald's and Marketing to a Foodie World

Tangy Temptation: McDonald’s and Marketing to a Foodie World Thomas R. Werner Whether boasting over the latest kill while it sizzled over a pre-historical fire or chatting about an enterprising chef in a contemporary upscale restaurant, humans have always bonded over food. “From primitive times,” Mark Meister writes, food “has been intimately involved in creating identification and consubstantiation” (2001, p. 175). Food gave people a pursuit that redefined the entire human experi- ence. Mary Douglas states that the meal is what brought humans “from hunter and gatherer to market-conscious consumer” (in Meister, 2001, p. 170). In our market- conscious age, the collection and discussion of food is a serious hobby, manifested in user-created reviews and independent food blogs. The term “foodie,” mockingly coined in Ann Barry and Paul Levy’s 1984 book The Official Foodie Handbook, once represented a snobby subset of Americans. However, with a proliferation of food media, food-pursuit is more and more accessible to those without a lot of dispos- able income, making the “foodie” a subset that grows daily. With a little bit of in- formation, the foodies feels adequately fit for publishing their own opinions about the quality of food in restaurants or at a friend’s house (Fattorini, 1994). Originally, the “foodie” acquired this casual-yet-obsessive learning through food publications and programming, but with more and more food media available to a mainstream audience, anybody can be a foodie now. Beyond using food as a delineator of socioeconomic status, the foodie subset has raised restaurants to be places of recreation in addition to being places of nour- ishment. -

Veg-‐Centric Menus

Veg-centric Menus 2011 Introduction Whether it’s meat-loving chefs embracing “vegetable butchery” or the new ways veggie burgers are showing up on even the beefiest of hamburger menus, the topics of vegetarianism, veganism, flexitarianism, pescatarianism and “Meatless Mondays” get weekly attention in November newspapers across the country. Beyond the media hype, a few forces are driving the interest in meatless fare: the local food movement and the popularity of farmers markets have been giving produce a boost for several years now. Consumers are trying to find interesting ways to eat better-for-you foods. Once limited to tofu and other meat stand-ins, today’s meat-free options have improved greatly, and chefs are seeing the value in letting produce star on the plate. And as beef and other protein prices rise, vegetarian menu options become a cost-effective alternative. Meat-free options are getting a second look, and when they taste good, diners will return to them. While vegetarians and vegans may represent a small part of the market—experts put the figure around 3%—there are plenty of reasons to add more vegetable options to any menu, and inventive menus are showing that there are more tantalizing ways to do so. This reports takes a closer look at the “why's and how's” of taking a more veggie-centric approach to menu development, through all segments of the industry. Room for Growth Top 10 Vegetarian Vegetarian menu item claims are up 28% (2011 vs. 2008). Pizza emerges as the number Menu Items/Dishes: one vegetarian menu item. -

M J P L K G H K Q R

MAP DIRECTORY 5 ST. GEORGE BOULEVARD 151 254 D O R A 250 V E Y L A Q P U W O N B ST. GEORGE A R C GARAGE I O R B 0 221 E R 4 2 A M 250 0 H A 3 2 L A N R 0 0 O 2 I T A 162 N Q 170 172 186 FLEET STREET FLEET STREET Over 85 Brand Name & Designer Outlets! 141 145 180 191 157 159 161 163 177 199 171 181 H L K 192 155 170 T E E E 171 FLEET E G E G TANGER 153 165 G A GARAGE 151 R A A MARINER S T S NATIONAL S S S S OUTLETS S GARAGE A T A 150 A BLVD. 141 P P HARBOR P R N N O C G R G O B . A A E D R R R M B M 0 F N A M L 4 1 L R K R I H O RI J H E L E T 121 A N T A 120 T O S O A N A X T M O P O E W NA I 188 W T L L T 100 H TRAVEL U AR 108 110 112 116 120 122 128 136 138 140 142 144 152 156 162 164 168 172 174 178 180 184 BO O RV R IEW PLAZA A E VE. G N WATERFRONT STREET A WATERFRONT STREET T 137 139 141 145 149 153 165 167 171 173 177 181 185 PROXIMITY MAP ATM D 152 152 B 138 140 144 146 156 158 160 168 A NATIONAL PLAZA RD EVA 200 141 OUL 145 2 155 OR B 300 HARB C NAL NATIO E ATTRACTIONS 1 Water Taxis, Dinner Cruises, ZA PLA 6 Kayaks/Peddle Boats EL RAV T 3 2 Plaza Entertainment 3 RD The Awakening VA LE OU 4 Marina R B RBO HA 5 The Plateau AL ION AT 6 N 1 Carousel 7 4 The Capital Wheel/Brews & Bites by Wolfgang Puck 8 Urban Pirates 8 LEGEND Public Safety Office P Public Parking 7 Post Office Services ATM ATM Public Restrooms Metrobus Stop CLOTHING & SHOES K-191 Nando’s Peri-Peri PERSONAL CARE & SERVICES K-181 Betty D-146 Potbelly Sandwich Shop M-120 Bella Cosmetic Surgery B-141 The Black Dog M-110 Subway J-174 Capital Spine & Pain Center L-142 Carhartt See Map Subway (at Sunoco) Q-162 CVS Pharmacy L-165 Cariloha Bamboo L-141 GIFTS AND HOME GOODS Divine Nail Spa J-172 Comfort One Shoes K-159 A-177 GNC L-165 Del Sol Color Change AMERICA! K-161 Harbor Cleaners A-185 K-171 Art Whino Harley-Davidson Q-221 Harbor Medical & Urgent Care L-153 House of JonLei Atelier A-173 Build-A-Bear Workshop L-125 Harborside Surgery Center J-168 Jos. -

BEST SANDWICHES on the BEACH Served Daily 8:00 Am – Close /- Captain’S Hour Specials 3Pm-5Pm

BEST SANDWICHES ON THE BEACH Served Daily 8:00 am – close /- Captain’s Hour Specials 3pm-5pm SANDWICHES, BURGERS & SLIDERS OH MY! Served on Island White or Wheat Roll, and cooked at medium or above. Accompanied by fries or coleslaw (substitute onion rings for 1.00) along with lettuce, tomato, onion and pickle. Add 0.75 for mushrooms or sauteed onion. Veggie Burger 9.95 *American Burger 9.95 Southwest Black Bean Burger served on Multi-grain bun. Classic 8 oz Black Angus burger with American cheese, Served with sliced avocado and a side of Chipotle Mayo. lettuce, tomato, onion & pickle on the side. Roessler Burger 9.95 *Patty Melt 9.95 (Named for Grandpa Roessler’s grandson Brian!) 8 oz Black Angus burger with sauteed onions, 8 oz. Black Angus burger with bacon, sauteed onions, Swiss cheese, served on grilled rye bread. American cheese, lettuce, tomato, onion & pickle on the side. *Sunset Burger 9.95 8 oz Black Angus burger with sauteed mushrooms, “The Homewrecker” 9.95 Swiss cheese, lettuce, tomato, and onion. This is a half pound hot dog! Any questions? Any beer on the menu will do with this baby! Italian Grinder 9.95 Add cheese or chili for 1.50 8” sub sandwich - ham, salami, capicola, pepperoni, and provolone cheese. Served with lettuce, tomato, onion & pickle on the side.. Yucatan Sunfish Tacos 13.95 Two flour tortilla shells stuffed with Tilapia, 10.95 Buffalo Chicken Sandwich topped with green cabbage, diced tomatoes, Lightly breaded, fried chicken breast tossed in your refreshing cilantro and a touch of ranch choice of mild, medium, or hot buffalo Wing sauce with dressing. -

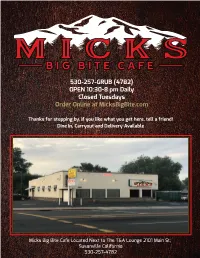

OPEN 10:30-8 Pm Daily Closed Tuesdays Order Online at Micksbigbite.Com

530-257-GRUB (4782) OPEN 10:30-8 pm Daily Closed Tuesdays Order Online at MicksBigBite.com Thanks for stopping by, if you like what you get here, tell a friend! Dine In, Carryout and Delivery Available Micks Big Bite Cafe Located Next to The T&A Lounge 2101 Main St, Susanville California 530-257-4782 DESSERTS Chocolate Cake 6.99 Big Fat Brownie 5.25 Berry Cobbler 6.99 Milkshake (starts at) 5.99 Carrot Cake 6.99 Ice Cream Cone 3.99 SPECIALTY DRINKS AND SODAS Pepsi, Diet, Mist, Dr, Root Beer 2.99 Mocha 4.95 Lemonade 2.99 Espresso 3.50 Iced Tea 2.99 Latte 4.25 Arnold Palmer 3.25 Chai Tea 4.95 Italian Sodas 3.50 Blended Mocha 5.75 KIDS & LITTLE PEEPS Cheeseburger & Fries 6.99 Mini Corn Dogs & Fries 7.25 Mac n Cheese 5.25 Kids Spaghetti (Dinner Only) 7.99 Kids Mini Pizza 6.99 Kids Alfredo (Dinner Only) 7.99 PB&J Sliders 5.25 Cold Turkey /Ham Sandwich & Chips 7.50 MICKSJoin Today BIGand Get REWARDS Rewarded with 50% OFF And Special Insider Updates *Excludes Alcohol WARNING: HEALTH WARNING ADVISORY, THIS RESTAURANT SERVES FISH AND OTHER SEAFOODS AND USES FRYERS, GRIDDLES AND SHARED COOKING EQUIPMENT TO COOK AND TO PREPARE THEM. THERE IS AN ALLERGAN RISK ASSOCIATED WITH CONSUMING OUR FOOD IF YOU HAVE SENSITIVITY TO SEAFOOD, RAW MEAT, OR NUTS. EGGS AND OTHER MEAT PRODUCTS THAT MAY BE ORDERED UNDERCOOKED AS AN OPTION. IF YOU SUFFER FROM SENSITIVITY, CHRONIC ILLNESS OF THE LIVER, STOMACH OR BLOOD OR HAVE OTHER IMMUNE DISORDERS, YOU SHOULD CONSIDER NOT EATING HERE. -

1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION VICTORIA GUSTER-HINES and DOMINECA NEAL, P

Case: 1:20-cv-00117 Document #: 1 Filed: 01/07/20 Page 1 of 103 PageID #:1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION VICTORIA GUSTER-HINES and DOMINECA NEAL, Plaintiffs, vs. Case No. McDONALD’S USA, LLC, a Delaware limited liability company, Jury Trial Demanded McDONALD’S CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation, STEVEN EASTERBROOK, CHRISTOPHER KEMPCZINSKI, and CHARLES STRONG Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR DEPRIVATIONS OF CIVIL RIGHTS Plaintiffs, Victoria Guster-Hines and Domineca Neal, by attorneys Carmen D. Caruso and Linda C. Chatman, bring suit under the Civil Rights Act of 1870 (42 U.S.C. §1981) against Defendants McDonald’s USA, LLC, McDonald’s Corporation, Steven Easterbrook, Christopher Kempczinski, and Charles Strong to redress intentional race discrimination, disparate treatment, hostile work environment and unlawful retaliation. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs Vicki Guster-Hines and Domineca Neal are African American senior executives at McDonald’s USA, LLC, the franchisor of the McDonald’s 1 Case: 1:20-cv-00117 Document #: 1 Filed: 01/07/20 Page 2 of 103 PageID #:1 restaurant system in the United States. They bring suit to redress McDonald’s continuing pattern and practice of intentional race discrimination that should outrage everyone, especially those who grew up going to McDonald’s and believing the “Golden Arches” were swell. 2. Vicki joined McDonald’s in 1987 and Domineca joined McDonald’s in 2012. They are highly qualified, high-achieving franchising executives, but McDonald’s subjected them to continuing racial discrimination and hostile work environment impeding their career progress, even though they both did great work for McDonald’s, which the Company consistently acknowledged in their performance reviews. -

Perspectives on Retail and Consumer Goods

Perspectives on retail and consumer goods Number 7, January 2019 Perspectives on retail and Editor McKinsey Practice consumer goods is written Monica Toriello Publications by experts and practitioners in McKinsey & Company’s Contributing Editors Editor in Chief Retail and Consumer Goods Susan Gurewitsch, Christian Lucia Rahilly practices, along with other Johnson, Barr Seitz McKinsey colleagues. Executive Editors Art Direction and Design Michael T. Borruso, To send comments or Leff Communications Allan Gold, Bill Javetski, request copies, email us: Mark Staples Consumer_Perspectives Data Visualization @McKinsey.com Richard Johnson, Copyright © 2019 McKinsey & Jonathon Rivait Company. All rights reserved. Editorial Board Peter Breuer, Tracy Francis, Editorial Production This publication is not Jan Henrich, Greg Kelly, Sajal Elizabeth Brown, Roger intended to be used as Kohli, Jörn Küpper, Clarisse Draper, Gwyn Herbein, the basis for trading in the Magnin, Paul McInerney, Pamela Norton, Katya shares of any company or Tobias Wachinger Petriwsky, Charmaine Rice, for undertaking any other John C. Sanchez, Dana complex or significant Senior Content Directors Sand, Katie Turner, Sneha financial transaction without Greg Kelly, Tobias Wachinger Vats, Pooja Yadav, Belinda Yu consulting appropriate professional advisers. Project and Content Managing Editors Managers Heather Byer, Venetia No part of this publication Verena Dellago, Shruti Lal Simcock may be copied or redistributed in any form Cover Photography without the prior written © Rawpixel/Getty Images consent of McKinsey & Company. Table of contents 2 Foreword by Greg Kelly 4 12 22 26 Winning in an era of A new value-creation Agility@Scale: Capturing ‘Fast action’ in fast food: unprecedented disruption: model for consumer goods growth in the US consumer- McDonald’s CFO on why the A perspective on US retail The industry’s historical goods sector company is growing again In light of the large-scale value-creation model To compete more effectively Kevin Ozan became CFO of forces disrupting the US retail is faltering. -

Gentlemen Cows, Mcjobs and the Speech Police: Curiosities About

Gentlemen Cows, McJobs and the Speech Police: Curiosities about language and law by Roger W. Shuy 1 Table of contents 2 Introduction 6 Problems with legal expressions 7 Gentlemen cows and other dirty words 8 Are we inured yet? 10 Person of interest 13 Reading the government’s mind 16 Legal uses of and/or…or something 20 Pity the poor virgule 22 Water may or may not run through it 24 McMissiles in Virginia 27 What’s the use of “use” anyway? 30 Banned words in the courtroom 33 Un-banning a banned word 36 Banning “rape” in a rape trial 37 “Official” Hispanic interns 41 Don’t call me doctor or someone will call the police 44 Getting a hunting license in Montana 46 The great Montana parapet battle 52 Weak and wimpy language 54 2 Proximate cause 57 Justice Scalia’s “buddy-buddy” contractions 63 Reasonable doubt about reasonable doubt 66 Reasonable doubt or firmly convinced ? 70 Do we have to talk in order to remain silent? 74 Arizona knows 76 It’s only semantics 80 2 Problems with language in criminal cases 85 Speaking on behalf of 86 On explicitness and discourse markers 91 Not taking no for an answer 97 Speech events in a kickback case 100 The recency principle and the hit and run strategy 107 Meth stings in the state of Georgia 109 The Pellicano file 113 The DeLorean saga 116 BCCI in the news again 121 The futility of Senator Williams’ efforts to say no 124 On changing your mind in criminal cases 128 Texas v. -

Mcdonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1994 Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985 Kathleen D. Toerpe Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Toerpe, Kathleen D., "Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985" (1994). Dissertations. 3457. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3457 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Kathleen D. Toerpe LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMALL FRY, BIG SPENDER: MCDONALD'S AND THE RISE OF A CHILDREN'S CONSUMER CULTURE, 1955-1985 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY KATHLEEN D. TOERPE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY, 1994 Copyright by Kathleen D. Toerpe, 1994 All rights reserved ) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank McDonald's Corporation for permitting me research access to their archives, to an extent wider than originally anticipated. Particularly, I thank McDonald's Archivist, Helen Farrell, not only for sorting through the material with me, but also for her candid insight in discussing McDonald's past. My Director, Lew Erenberg, and my Committee members, Susan Hirsch and Pat Mooney-Melvin, have helped to shape the project from its inception and, throughout, have challenged me to hone my interpretation of McDonald's role in American culture. -

Carry out Menu

Wednesday - Friday Saturday & Sunday 4 PM- 8PM 3 PM- 8PM CARRY OUT MENU STARTERS RIVERBAY NACHOS CHICKEN TENDERS Fresh corn tortilla chips topped with queso, fresh jalapeno peppers, Beer battered tenders and fried. Served with honey mustard. pico de gallo, and cheddar jack cheese. $10.99 Served with salsa and sour cream $9.99 Add chicken $12.99 WINGS Steak $14.99 Crispy house seasoned fresh jumbo wings tossed in your choice of sauce: Chesapeake, BBQ, Hot, Mild, Sweet Thai Chili, Mango Habanero, RIVERBAY PRETZEL Maryland Buffalo, Naked (GF) Roadhouse signature crab dip on a jumbo soft pretzel smothered with Served with celery and dip $14.99 melted jack & cheddar cheese. $16.99 STEAMED SHRIMP QUESADILLA Peel and eat shrimp steamed in Natty Boh and Old Bay 1 lb Pico de gallo and cheddar jack cheese folded into a warm flour tortilla. $16.99 Served with salsa and sour cream $8.99 Chicken $11.99 RIVERBAY LOADED TOTS (GF) Steak $13.99 Golden brown tots topped with bacon, cheddar jack cheese, scallions, and side of sour cream $11.99 SOUPS AND SALADS Dressings: Balsamic Vinaigrette, Italian, Ranch, Blue Cheese, Thousand Island, Caesar, Honey Mustard, Citrus Cranberry CREAM OF CRAB GARDEN SALAD Homemade creamy crab Fresh mixed greens topped with carrots, cucumbers, red Cup $5.99 Bowl $7.99 onion, tomato and croutons $7.99 CRISPY BACON CHICKEN SALAD CAESAR SALAD Fresh mixed greens with crispy fried chicken or grilled Crispy Romaine lettuce tossed in a creamy Caesar dressing, chicken topped with bacon, tomato, egg, croutons, and parmesan cheese $8.99 red onion, and cheddar jack cheese $13.99 Add Grilled Chicken $4.99, Steak $7.25, Crab Cake $ Market Price ROADHOUSE BURGERS Our Angus beef burgers cooked your way on a buttery brioche bun.