Essays on Short Selling and Margin Trading in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ping an Bank Co., Ltd. 2013 First Quarterly Report

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. OVERSEAS REGULATORY ANNOUNCEMENT This announcement is made pursuant to Rules 13.09 and 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. “The Announcement of Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Ltd. in relation to the Disclosure of 2013 First Quarterly Report of Ping An Bank”, which is published by Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Ltd. on the website of Shanghai Stock Exchange and certain designated newspapers (except the attachment) in the PRC, is reproduced herein for your reference. By Order of the Board Yao Jun Company Secretary Shenzhen, PRC, April 23, 2013 As at the date of this announcement, the Executive Directors of the Company are Ma Mingzhe, Sun Jianyi, Ren Huichuan, Ku Man and Yao Jason Bo; the Non-executive Directors are Fan Mingchun, Lin Lijun, Li Zhe and Guo Limin; the Independent Non-executive Directors are Zhang Hongyi, Chen Su, Xia Liping, Tang Yunwei, Lee Carmelo Ka Sze, Woo Ka Biu Jackson and Stephen Thomas Meldrum. Stock Code:601318 Stock Short Name: China Ping An Serial No.:Lin 2013-018 THE ANNOUNCEMENT OF PING AN INSURANCE (GROUP) COMPANY OF CHINA, LTD. IN RELATION TO THE DISCLOSURE OF 2013 FIRST QUARTERLY REPORT OF PING AN BANK The board of directors and all directors of Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Ltd. -

SZSE Weekly Bulletin 2 July, 2021

Shenzhen Stock Exchange Market Bulletin July 02, 2021 (Issue 58) Market Summary Daily Trading Value (June 21 – July 02) By market closed on July 02, 2021 Listed Companies (No.) 2,456 - Main Board 1,478 - ChiNext Market 978 Funds 479 Bonds 9,192 Market Cap. (US$ bn) 5,582.2 SZSE Component Index (June 21 – July 02) - Main Board 3,634.4 Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) - ChiNext Market 1,947.7 Average Turnover Ratio 1.95 Average P/E Ratio 30.85 No. of IPO (YTD) 106 Most Active Companies 1 East Money Information Co., Ltd. (300059) ChiNext Index (June 21 – July 02) 2 Byd Company Limited (002594) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., 3 Limited (300750) Top Gainers 1 Qingdao Baheal Medical Inc. (301015) 2 Shenzhen Lihexing Co.,ltd. (301013) 3 Nanjing Railway New Technology Co.,ltd. SZSE 100 Index (June 21 – July 02) (301016) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Top Decliners 1 Steyr Motors Corp. (000760) Title 2 Northcom Group Co., Ltd. (002359) Zhejiang Cayi Vacuum Container Co., Ltd. Comments 3 (301004) For week of June 28-July 02, 2021 New Listing Ningbo Color Ningbo Color Master (301019) Ningbo Color Master Batch Co., Ltd. engages in production and sale of technical services of color masterbatch. In Master (301019) 2020, its operating income reached 430 million yuan with the net profit of 104.41 million yuan. Lihexing (301013) Lihexing (301013) Shenzhen Lihexing Co., Ltd. engages in R&D, production and sale of automation and intelligent equipment. -

Weekly Bulletin

24 June, 2013 Issue 5 Market Bulletin Monday 24 June, 2013 (Issue 5) Highlights Market Review China's Overnight Interbank Rate Hits Major Shenzhen indices continued to decline in the week ended on 21 Record High June. Shenzhen Component Index lost 4.05% to close at 8136.05. SME China's Manufacturing Production Drops Index declined 3.76% closing at 4674.72. ChiNext Index dropped 3.99% to Nine-month Low to 1025.50. Total turnover for stocks and funds on SZSE last weeks PBC and BOE Establishes RMB 200 Bil- valued at US$67.22 billion. lion Currency Swap Line Central Huijin Increases Stakes in China The only sector index with gains is culture and communication, in- Banks creasing 3.26%. Top 3 gainers are Meisheng Cultural (002699), 35.COM China’s Overseas M&A Volume Grew (300051) and Extra ST Globe Union (002047). Longyuan Technolo- 200 Times in Past Decade gy(300105), Kanhoo Industry (300340) and Hanhe Cable (002498) are CSRC and CIRC Jointly Issued Pilot Measures for Insurance Institutions to the Top 3 decliners. The most active stocks last week were Vanke A Set up Fund Management Companies (000002), Letv (300104)and Ping An Bank (000001). Securities Houses Probed by CSRC Four Types of Innovative ETF Approved in June Market News Chinese Government Supports First- Time Home Buyers China's Overnight Interbank Rate Hits Record High Shuanghui-Smithfield Merger Meets The Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (SHIBOR) overnight rate has Challenge Adjustment Made to the Component been rising since the beginning of June, gaining 578.40 base points Stocks of SZSE Indices and hitting a record high of 13.44% last Thursday. -

Essays on Mispricing in the Chinese Stock Market 302

MO ZHANG ESSAYS ON MISPRICING IN THE CHINESE STOCK MARKET 302 EKONOMI OCH SAMHÄLLE Along with Chinese economic development, the Chi- efficient market theory. The second essay uses this phe- ECONOMICS AND SOCIETY nese stock market is growing rapidly, and is now the sec- nomenon as a natural experiment to test whether a new ond largest stock market in the world. However, despite reform policy, namely granting permission for short selling, its size, the Chinese stock market trades like the wildest benefits the efficiency of the Chinese stock market. When emerging markets, with huge volatility, big boom and bust the Chinese government lift the ban on short selling in the cycles, driven by fast-trading individual investors, and Chinese stock market, mispricing decreases significantly, heavy involvement from the government. Owing to the even though the volume of short selling in the Chinese stock peculiarity of the Chinese economic and political system, market is trivial relative to total trading volume. Instead of there are some unique structures within the Chinese stock studying a particular set of stocks, the third essay focuses market. In one sense, this makes the Chinese stock market on the mispricing formation mechanism at the general mar- an interesting laboratory. This dissertation comprises three ket level. The market results show that both the resale op- single-authored essays. The first two analyze a special tion and inflation illusion hypotheses can explain the level phenomenon, called B-share discounts in the Chinese stock of market mispricing. Only investors’ heterogeneous beliefs market, seeking to explain why this phenomenon exists affect the volatility of market mispricing, in line with the re- from the perspective of exchange risk. -

2009 Annual Report 2009

2009 Annual Report Annual Report 2009 Important The Board of Directors, Supervisory Committee and the Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company confirm that this annual report does not contain any false information, misleading statements or material omissions, and collectively and individually accept responsibility for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents of this annual report. Mr. Hou Weigui, Chairman of the Company, Mr. Wei Zaisheng, Chief Financial Officer of the Company and Mr. Shi Chunmao, Head of Finance Division of the Company, hereby declare that they warrant the truthfulness and completeness of the financial reports contained in this annual report. This annual report has been considered and approved at the second meeting of the Fifth Session of the Board of Directors of the Company. Mr. Zhang Junchao, Director, was unable to attend the meeting due to work reasons and authorised in writing Mr. Hou Weigui, Chairman, to vote on his behalf. Mr. Li Jin, Independent Director, was unable to attend the meeting due to work reasons and authorised in writing Mr. Chen Naiwei, Independent Director, to vote on his behalf. Mr. Tan Zhenhui, Independent Director, was unable to attend the meeting due to work reasons and authorised in writing Mr. Chen Naiwei, Independent Director, to vote on his behalf. There are no Directors, Supervisors or senior management who do not warrant or who dispute the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents of this annual report. The respective financial statements of the Group for the year ended 31 December 2009 were prepared in accordance with PRC Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises (“PRC ASBEs”) and with Hong Kong Financial Reporting Standards (“HKFRSs”) respectively, and had been audited by Ernst & Young Hua Ming and Ernst & Young, and an unqualified auditors’ report has been issued by each of them. -

SZSE Weekly Bulletin 23 April, 2021

Shenzhen Stock Exchange Market Bulletin April 23, 2021 (Issue 49) Market Summary Daily Trading Value (April 12 – April 23) Listed Companies (No.) 2,415 - Main Board 1,474 - ChiNext Market 941 Funds 453 Bonds 8,835 Market Cap. (US$ bn) 5,264.5 - Main Board 3,579.6 SZSE Component Index (April 12 – April 23) - ChiNext Market 1,684.9 Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Average Turnover Ratio 1.93 Average P/E Ratio 31.42 No. of IPO (YTD) 62 Most Active Companies ChiNext Index (April 12 – April 23) 1 Boe Technology Group Co., Ltd (000725) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) 2 East Money Information Co., Ltd. (300059) Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., 3 Limited (300750) Top Gainers Nanjing Sunlord Electronics Corporation 1 Ltd. (300975) Fujian Wanchen Biotechnology Co.,ltd 2 (300972) Shenzhen Silver Basis Technology Co.,ltd SZSE 100 Index (April 12 – April 23) 3 (002786) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Top Decliners 1 China Dive Company Limited (300526) Title Kangde Xin Composite Material Group 2 Co.,ltd. (002450) Comments 3 Huawen Media Group (000793) New Listing Wanchen Biotechnology (300972) Wanchen Biotechnology Fujian Wanchen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. engages in factory cultivation and sale of edible fungi. In 2019, its operating income reached 451 million yuan with the net profit of 92.19 million yuan. (300972) Tarry Electronics (300976) Dongguan Tarry Electronics Co., Ltd. engages in sale of electronics devices and 3C intelligent equipment. In Tarry Electronics (300976) 2019, its operating income reached 867 million yuan with the net profit of 226.62 million yuan. -

Price Change Prediction of Ultra High Frequency Financial Data Based on Temporal Convolutional Network

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Computer Science 00 (2021) 000–000 www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia Information Technology and Quantitative Management (ITQM 2020&2021) Price change prediction of ultra high frequency financial data based on temporal convolutional network Wei Daia,b,c, Yuan Ana,b,c, Wen Longa,b,c,∗ aSchool of Economics and Management, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100190, P.R.China bResearch Center on Fictitious Economy and Data Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100190, P.R.China cKey Laboratory of Big Data Mining and Knowledge Management, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100190, P.R.China E-mail address: [email protected]; [email protected]. Abstract Through in-depth analysis of ultra high frequency (UHF) stock price change data, more reasonable discrete dynamic distribution models are constructed in this paper. Firstly, we classify the price changes into several categories. Then, temporal convolutional network (TCN) is utilized to predict the conditional probability for each category. Furthermore, attention mechanism is added into the TCN architecture to model the time-varying distribution for stock price change data. Empirical research on constituent stocks of Chinese Shenzhen Stock Exchange 100 Index (SZSE 100) found that the TCN framework model and the TCN (attention) framework have a better overall performance than GARCH family models and the long short- term memory (LSTM) framework model for the description of the dynamic process of the UHF stock price change sequence. In addition, the scale of the dataset reached nearly 10 million, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous attempt to apply TCN to such a large-scale UHF transaction price dataset in Chinese stock market. -

Carrots and Sticks Sustainability Reporting Policies Worldwide – Today’S Best Practice, Tomorrow’S Trends

CARROTS AND STICKS Sustainability reporting policies worldwide – today’s best practice, tomorrow’s trends 2013 edition CARROTS AND STICKS 2 Sustainability reporting policies worldwide - today’s best practice, tomorrow’s trends Table of Contents Carrots and Sticks Forewords 6 Executive Summary 8 Introduction 10 What are the main trends? 13 1. A global increase in the amount of policy and regulation for organizational reporting 13 2. An increasing amount of policy is inspired by, or based on, a report or explain approach 14 3. Development, growth and harmonization of reporting frameworks 16 4. Developments in the organizations that are reporting 16 a. The main focus is on large companies 16 b. Increasing voluntary reporting by SMEs 17 c. State-owned companies 17 5. Sustainability reporting as a listing requirement for stock exchanges: a popular option for emerging and developing countries 17 6. The United Nations now requests that governments stimulate sustainability reporting through best practice 17 7. Other drivers of ‘more reporting’ 19 8. Challenges to the momentum 21 Sustainability Frameworks. Which one for reporting? 22 In-depth Profiles 25 Policies and Initiatives 37 Assurance Standards 80 Conclusions 82 The way ahead 83 Glossary 84 References 85 Disclaimer 89 Acknowledgements 90 3 CARROTS AND STICKS Project Partners United Nations Environment Programme The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (UNEP) UNEP represents the United Nations’ environmental conscience. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) promotes the use of Based in Nairobi, Kenya, its mission is to provide leadership and sustainability reporting as a way for organizations to become more encourage partnership in caring for the environment by inspiring, sustainable and contribute to a sustainable global economy. -

SZSE Weekly Bulletin 11 June, 2021

Shenzhen Stock Exchange Market Bulletin June 11, 2021 (Issue 55) Market Summary Daily Trading Value (May 31 – June 11) By market closed on June 11, 2021 Listed Companies (No.) 2,442 - Main Board 1,476 - ChiNext Market 966 Funds 464 Bonds 9,079 Market Cap. (US$ bn) 5,656.6 SZSE Component Index (May 31 – June 11) - Main Board 3,730.8 Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) - ChiNext Market 1,925.8 Average Turnover Ratio 1.93 Average P/E Ratio 30.98 No. of IPO (YTD) 92 Most Active Companies 1 Byd Company Limited (002594) ChiNext Index (May 31 – June 11) 2 East Money Information Co., Ltd. (300059) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., 3 Limited (300750) Top Gainers Shenzhen Sosen Electronics Co.,ltd. 1 (301002) 2 Meter Instruments Co., Ltd. (301006) 3 Jiangsu Hoperun Software Co., Ltd. (300339) SZSE 100 Index (May 31 – June 11) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Top Decliners 1 Northcom Group Co., Ltd. (002359) Title 2 Steyr Motors Corp. (000760) Comments Europol Intelligent Network Co.,ltd. 3 (002711) For week of June 7-June 11, 2021 New Listing Sosen (301002) Sosen (301002) Shenzhen Sosen Electronics Co., Ltd. engages in R&D, production and sale of LED driving power products. In Meter (301006) 2020, its operating income reached 676 million yuan with the net profit of 99.49 million yuan. Hongchang Technology Meter (301006) Meter Instruments Co., Ltd. engages in R&D, production and sale of ultrasonic water meters and series (301008) products related to heat meter. -

Prospectus- Global Offering(H)

Stock Code: 03958 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability under the Chinese corporate name “東方證券股份有限公司” and carrying on business in Hong Kong as “東方證券” (in Chinese) and “DFZQ” (in English)) GLOBAL OFFERING Joint Sponsors Financial Advisor Joint Global Coordinators Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers IMPORTANT IMPORTANT: If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this prospectus, you should obtain independent professional advice. (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability under the Chinese corporate name “ ” and carrying on business in Hong Kong as “ ” (in Chinese) and “DFZQ” (in English)) Number of Offer Shares under the Global Offering 957,000,000 H Shares (comprising 870,000,000 H Shares to be offered by the Company and 87,000,000 Sale Shares to be sold by the Selling Shareholders, subject to the Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares 71,775,200 H Shares (subject to adjustment) Number of International Offer Shares 885,224,800 H Shares (subject to adjustment and the Over- allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price HK$9.35 per H Share, plus brokerage of 1.0%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% and Hong Kong Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars and subject to refund) Nominal value RMB1.00 per H share Stock code 03958 Joint Sponsors Financial Advisor Joint Global Coordinators Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers Зࡋ⳪暲 @.54-:'//4:+84':/54'2 Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. -

2013 Annual Report 2013 Annual Report Annual 2013

China CITIC Bank Corporation Limited 2013 Annual Report 2013 Annual Report Block C, Fuhua Mansion, No. 8 Chaoyangmen Beidajie, Dongcheng District, Beijing, China Postal Code : 100027 bank.ecitic.com Important Notice The Board of Directors, the Board of Supervisors, Corporate Introduction directors, supervisors, and senior management of the Bank ensure that the information contained Founded in 1987, CITIC Bank is one of the earliest established commercial bank during China’s reform and opening up and China’s first herein does not include any false records, commercial bank participating in financing at both domestic and international financial markets. It is renowned at home and abroad for misleading statements or material omissions, brushing numerous track records in the contemporary Chinese financial history. Over the years, it has made great contributions to China’s and assume several and joint liabilities for its truthfulness, accuracy and completeness. economic development. The meeting of the Board of Directors adopted As one of the leading domestic commercial banks in terms of capital strength, CITIC Bank has grown rapidly in the wave of economic the full text and summary of the 2013 Annual development in China and has become a national commercial bank with strong comprehensive competitive edges. In July 2013, CITIC Bank Report on 27 March 2014. 14 out of the 14 ranked 47th in terms of tier-one capital and 57th in terms of total assets among the “Top 1,000 World Banks” published by British magazine The Table of Contents eligible directors attended the meeting, including Banker, ranking among the best of all Chinese commercials banks. -

Weekly Bulletin

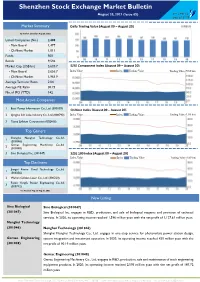

Shenzhen Stock Exchange Market Bulletin August 20, 2021 (Issue 65) Market Summary Daily Trading Value (August 09 – August 20) By market closed on Aug 20, 2021 Listed Companies (No.) 2,488 - Main Board 1,477 - ChiNext Market 1,011 Funds 500 Bonds 9,596 Market Cap. (US$ bn) 5,620.7 SZSE Component Index (August 09 – August 20) - Main Board 3,656.7 Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) - ChiNext Market 1,963.9 Average Turnover Ratio 2.04 Average P/E Ratio 30.73 No. of IPO (YTD) 142 Most Active Companies 1 East Money Information Co., Ltd. (300059) ChiNext Index (August 09 – August 20) 2 Qinghai Salt Lake Industry Co., Ltd. (000792) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) 3 Tianqi Lithium Corporation (002466) Top Gainers Shanghai Nenghui Technology Co.,ltd. 1 (301046) Gemac Engineering Machinery Co.,ltd. 2 (301048) 3 Sino Biological Inc. (301047) SZSE 100 Index (August 09 – August 20) Index Value Index Trading Value Trading Value (US$ bn) Top Decliners Jiangxi Firstar Panel Technology Co.,ltd. 1 (300256) Title 2 Wuhan Golden Laser Co., Ltd. (300220) Comments Fujian Yongfu Power Engineering Co.,ltd. 3 (300712) For week of Aug 16-Aug 20, 2021 New Listing Sino Biological Sino Biological (301047) (301047) Sino Biological Inc. engages in R&D, production, and sale of biological reagents and provision of technical services. In 2020, its operating income reached 1,596 million yuan with the net profit of 1,127.61 million yuan. Nenghui Technology (301046) Nenghui Technology (301046) Shanghai Nenghui Technology Co., Ltd.