A Forgotten Part of Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4¼N5 E0 4¼N5 4¼N4 4¼N4 4¼N4 4¼N5

#] Mullaghmore \# Bundoran 0 20 km Classiebawn Castle V# Creevykeel e# 0 10 miles ä# Lough #\ Goort Cairn Melvin Cliffony Inishmurray 0¸N15 FERMANAGH LEITRIM Grange #\ Cashelgarran ATLANTIC Benwee Dun Ballyconnell#\ Benbulben #\ R(525m) Head #\ Portacloy Briste Lough Glencar OCEAN Carney #\ Downpatrick 1 Raghly #\ #\ Drumcliff # Lackan 4¼N16 Manorhamilton Erris Head Bay Lenadoon Broad Belderrig Sligo #\ Rosses Point #\ Head #\ Point Aughris Haven ä# Ballycastle Easkey Airport Magheraghanrush \# #\ Rossport #\ Head Bay Céide #\ Dromore #– Sligo #\ ä# Court Tomb Blacklion #\ 0¸R314 #4 \# Fields West Strandhill Pollatomish e #\ Lough Gill Doonamo Lackan Killala Kilglass #\ Carrowmore ä# #æ Point Belmullet r Bay 4¼N59 Innisfree Island CAVAN #\ o Strand Megalithic m Cemetery n #\ #\ R \# e #\ Enniscrone Ballysadare \# Dowra Carrowmore i Ballintogher w v #\ Lough Killala e O \# r Ballygawley r Slieve Gamph Collooney e 4¼N59 E v a (Ox Mountains) Blacksod i ä# skey 4¼N4 Lough Mullet Bay Bangor Erris #\ R Rosserk Allen 4¼N59 Dahybaun Inishkea Peninsula Abbey SLIGO Ballinacarrow#\ #\ #\ Riverstown Lough Aghleam#\ #\ Drumfin Crossmolina \# y #\ #\ Ballina o Bunnyconnellan M Ballymote #\ Castlebaldwin Blacksod er \# Ballcroy iv Carrowkeel #\ Lough R #5 Ballyfarnon National 4¼N4 #\ Conn 4¼N26 #\ Megalithic Cemetery 4¼N59 Park Castlehill Lough Tubbercurry #\ RNephin Beg Caves of Keash #8 Arrow Dugort #÷ Lahardane #\ (628m) #\ Ballinafad #\ #\ R Ballycroy Bricklieve Lough Mt Nephin 4¼N17 Gurteen #\ Mountains #\ Achill Key Leitrim #\ #3 Nephin Beg (806m) -

450 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

450 bus time schedule & line map 450 Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry) View In Website Mode The 450 bus line (Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry): 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM (2) Louisburgh - Dooagh: 5:30 AM - 6:50 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 450 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 450 bus arriving. Direction: Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh 450 bus Time Schedule (Hudson's Pantry) Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Pantry) 15 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:20 AM - 8:05 PM Monday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dooagh Stop 530301 Tuesday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Keel Stop 530371 Wednesday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dugort Stop 530391 Thursday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Dooniver Junction Stop 553011 Friday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Bunnacurry Stop 638031 Saturday 7:10 AM - 7:20 PM Cashel Stop 638041 Achill Sound Stop 631421 450 bus Info Direction: Dooagh (The Pub) - Louisburgh (Hudson's Mulrany Stop 638061 Pantry) Stops: 15 Newport Stop 638111 Trip Duration: 124 min Line Summary: Dooagh Stop 530301, Keel Stop Mill Street Stop 555711 530371, Dugort Stop 530391, Dooniver Junction Grove Park, Westport Stop 553011, Bunnacurry Stop 638031, Cashel Stop 638041, Achill Sound Stop 631421, Mulrany Stop Westport Quay Stop 557161 638061, Newport Stop 638111, Mill Street Stop 555711, Westport Quay Stop 557161, Murrisk Stop Murrisk Stop 500021 500021, Lecanvey Stop 545491, Kilsallagh Stop 557171, Louisburgh Stop 553111 -

West Coast, Ireland

West Coast, Ireland (Slyne Head to Erris Head) GPS Coordinates of location: Latitude: From 53° 23’ 58.02”N to 54° 18’ 26.96”N Longitude: From 010° 13” 59.87”W to 009° 59’ 51.98”W Degrees Minutes Seconds (e.g. 35 08 34.231212) as used by all emergency marine services Description of geographic area covered: The region covered is the wild and remote west coast of Ireland, from Slyne Head north of Galway to Erris Head south of Sligo. It includes Killary Harbour, Clew Bay, Black Sod Bay, Belmullet, and the islands of Inishbofin, Inishturk, Clare, Achill, and the Inishkeas. It is an area of incomparable charm and natural beauty where mountains come down to the sea unspoilt by development. It is also an area without marinas, or easy access to marine services. Self-sufficiency is absolutely necessary, along with careful navigation around a rocky lee coastline in prevailing westerlies. A vigilant watch for approach of frequent Atlantic gales must be kept. Inishbofin is reported to be the most common stopover of visiting foreign-flagged yachts in Ireland, of which there are very few on the West coast. Best time to visit is May-September. 1 24 May 2015 Port officer’s name: Services available in area covered: Daria & Alex Blackwell • There are no marinas in the west of Ireland between Galway and Killybegs in Donegal, so services remain difficult to access. Haul out facilities are now available in Kilrush on the Shannon River and elsewhere by special arrangement with crane operators. • Visitor Moorings (Yellow buoy, 15 tons): Achill / Kildavnet Pier, Achill Bridge, Blacksod, Clare Island, Inishturk, Rosmoney (Clew Bay), Leenane. -

Inspectors of Irish Fisheries Report

REPORT OF THE INSPECTORS OF IRISH FISHERIES ON THE SEA AND INLAND FISHERIES OF IRELAND, FOR 1888. Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by Command oh Her Majesty DUBLIN: PRINTED FOR HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE BY ALEXANDER THOM & CO. (Limited), And to be purchased, either directly or through any Bookseller, from Eyre and Spottiswoode, East Harding-street, Fetter-lane, E.C., or 32, Abingdon-street, Westminster, S.W.; or Adam and Charles Black, 6, North Bridge, Edinburgh ; or Hodges, Figgis, and Co., 104, Grafton-strect, Dublin. 1889, j-Q—5777.] Price Is. CONTENTS. Page. REPORT,..................................................................................................................................................... 5 APPENDIX,..................................................................................................................................................... 80 Appendix SEA AND OYSTER FISHERIES. No. 1. —Abstract of Returns from Coast Guard, ....... 80 2. —Statistics of Fish landed on the Irish Coast during the year 1888, .... 81 3. —By-Laws in force, .......... 82 4. —Oyster Licenses revoked, ......... 88 5. —Oyster Licenses in force, ......... 90 Irish Reproductive Loan Fund and Sea and Coast Fisheries Fund. 6. —Proceedings for the year 1888, and Total amount of Loans advanced, and Total Repayments under Irish Reproductive Loan Fund for thirteen years ending 31st December, 1888, 94 7. —Loans applied for and advanced under Sea and Coast Fisheries Fund for the year ending 31st December, 1888, .......... 94 8. —Amounts available and applied for, 1888, ... ... 95 9. —Total Amounts Advanced, the Total Repayments, the Amounts of Bonds or Promissory Notes given as Security, since Fund transferred in 1884 to be administered by Fishery Depart ment, to 31st December, 1888, together with the Balance outstanding, and the Amount in Arrear, ......... 96 10. —Fishery Loans during the year ending 31st December, 1888, .... -

Achill Heinrich Böll Association, Cashal Achill, Co

Annual Heinrich Böll Weekend May 4th – May 6th 2018 Achill Island Ireland Friday May 4th Full Weekend € 130 19:00 Registration and Welcome Reception. Cyril Gray Hall Dugort 19:30 Official Opening: H.E. Deike Potzel: Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1987 - 1992 Foreign Service Academy of the Federal Foreign Ministry, Bonn. English and French Language and Literature Studies, Humboldt University Berlin. Since 2017 Ambassador, German Embassy, Dublin, Ireland / 2014-2017 Deputy Director-General for Central Services, Foreign Ministry, Berlin / 2012-2014 Head of the Personal Office of Federal President Joachim Gauck/ 2008- 2012/Deputy Head of Division for Personal, Staff Development and Planning, Foreign Ministry, Berlin. Presentation of Essay Prizes by H.E. Deike Potzel. 20:30 Patricia Byrne: The Preacher and the Prelate: Achill Mission Colony and the battle for souls in famine Ireland. Book launch by Sheila McHugh with a response to the book by Hilary Tulloch and reading by Patricia Byrne. The Preacher and the Prelate tells the extraordinary story of an audacious fight for souls on famine- ravaged Achill Island in the nineteenth century. Religious ferment sweeps Ireland in the early 1800s and evangelical clergyman Edward Nangle sets out to lift the destitute people of Achill out of degradation and idolatry through his Achill Mission Colony. A settlement grows up on the slopes of Slievemore with cultivated fields, schools, a printing press and hospital. The Achill Mission colony attracts attention and visitors from far afield. In the years of the Great Famine the ugly charge of ‘souperism’, offering food and material benefits in return for religious conversion, tainted the Achill Mission’s work. -

Heinrich Böll Memorial Weekend

Heinrich Böll Memorial Weekend. st rd Achill Island Ireland May 1 – May 3 2015. Friday May 1 st 7.00 pm. Registration for weekend. Full Weekend €1 1 0 . Cyril Gray Memorial Hall, Dugort. 7.30pm Official Opening by : Ambassador Declan Kelleher . Permanent Representative of Ireland in the European Union. Ambassador Kelleher will give his opening address on the theme; " Culture, Diplomacy and Mutual Understanding". The 12th Annual Heinrich Boll Weekend will open with an address by H.E. Declan Kelleher, Permanent Representative of Ireland to the E.U. Prior to his appointment to Brussels he was Ambassador of Ireland to the People's Republic of China where he served from 2004 to 2013, and was instrumental in opening up trade and cultural links between Ireland and China . Ambassador Kelleher has long experience as a diplomat in the Department of Foreign Affairs both at home and overseas, including at the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations in New York, and at the Irish Embassy in Washington. He also served as Ireland's Ambassador to the E.U. Political and Security Committee from 2000 to 2004. He has spent time working in the private sector as an economic and financial analyst, specialising in global marine and oil industries. He holds a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from Oxford University. Presentation of Essay Competition prizes by Ambassador Declan Kelleher. 8.30pm The Prophet and the Bishop: the religious war between Edward Nangle 1800-1883 And Archbishop John MacHale 1791- 1881. Illustrated talk by Kevin Toolis. From the 1830s to the 1880s a great religious war raged in Connaught between Evangelical Protestants and the Catholic Church for the hearts of the poor. -

Comhalrle CONTAE MHAIGH EO =,Atit Aras an Chontae, Caislean a 'Bharraigh, Contae Mhaigh Eo

COMHAlRLE CONTAE MHAIGH EO =,atit Aras an Chontae, Caislean a 'Bharraigh, Contae Mhaigh Eo. Teileaf6in (094) 9024444 Fax (094) 9023937 Website: www.mayococo.ie Your Ref. Our Ref. grn July 2009. Administration Environmental Licensing Programme Office of Climate, Licensing & Resource Use Environmental Protection Agency Headquarters P.O. Box 3000 Johnstown Castle Estate County Wexford RE: Notice in accordance with Reaulation 18(ub) of the Waste Water Discharge fAuthorisation) Regulations 2007 APPLICATION: D0072-01- ACHILL ISLAND CENTRAL Dear Mr McLoughlin For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Further to your letter of 2gm May 2009, Ienclose the required responses to the queries raised in the correspondence. For clarity, the responses have been made point .by point with the original queries indicated in italics. Thank you, Yours sincerely Paddy Mahon Director of Services MAYO COUNTY COUNQ, Aras an Chontae, Castlebar, Co. Mayo. Tel: (094) 9024444 PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER EPA Export 26-07-2013:14:27:58 I Y.2 >: 7 "L*-, .-_ Achill Island Central Waste Water Discharge Licence Application Reguilation 18 Request REGULATION 16 COMPLIANCE REQUIREMENTS No. 1 Provide the name of the agglomeration to which the application relates. Answer 1 The name of the agglomeration is Achill Island Central No. 2 In Section B.9 (i) of the application form, the p.e. of the agglomeration is stated as being 4000. Please confirm that this figure includes the maximum average weekly loading for the agglomeration, to take account of the peak summer holiday season in Achill. Answer 2 The Treatment Plant was designed to cater for a 4,000 PE. -

The Famine in Mayo 1845-1850

The Famine in Mayo 1845-1850 A Mayo County Library Exhibition 1 Charles Edward Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury directed government relief measures during the famine, meticulously scrutinising all expenditure The Famine in Mayo 1845 - 1850 The Great Famine was one of the defining moments of Irish history. It marked a watershed in the history of the country causing a change so complete in the Irish social and economic fabric, that the people’s sensibilities would never be the same again. No longer could the Irish people trust to the land to provide constant sustenance. No longer could they rely on whatever security of tenure was allowed by the landlords, and more importantly they learned that their English political masters cared little for their plight. The Famine in Mayo is a portrait of the lives and deaths of the people as recorded by witnesses in books, newspapers and official records of that period. 1(a) The Famine in Mayo 1845 - 1850 The Potato Disease e first reports of blight appeared in September of 1845. For one third of the country’s population of eight million, the nutritious lumper potato was pratically the sole article of the diet. In County Mayo, it was estimated that nine tenths of the population depended on it. An acre and a half of land could provide enough potatoes to support a family for most of the year. Any other crops or animals the smallholder raised went to pay rent. A potato famine was a great calamity. THE POTATO CROP THE POTATO CROP PERSECUTION Mayo Constitution (11-11-1845) TO THE EDITOR OF AND STARVATION The Telegraph (19-8-1846) In some cases the damage is found, on THE CONSTITUTION Rathbane, 29th December, 1845 digging out the potatoes, to be only On Monday last upwards of 500 poor, partial, in other cases the injury and loss wretched, emaciated human beings are, very great. -

Mulranny Tourism Eden Brochure

Ballycastle 5 A MULRANNY TOURISM INITIATIVE TOURISM MULRANNY A 1 R314 Belmullet Excellence of Destination European A R314 N59 R313 R313 R315 Bangor Bellacorick N59 Crossmolina R294 364 Ballina Maumykelly N59 R iv e r R312 M Slieve Carr o y Blacksod Bay 721 600 N26 500 6 400 300 R315 200 B 100 a n W Ballycroy g o e r 627 s t T e Visitor Centre r r a Nephin Beg n Bunaveela i Slievemore l W Lough 311 a 672 y Nephin 806 Lough NATIONAL 700 Conn E 600 Achill Island Glennamong 500 400 688 Lough Keel PARK G 300 Bunacurry INISHBIGGLE 628 200 Acorrymore Lough N Croaghaun ANNAGH 100 ISLAND A 698 R319 Keel R Birreencorragh R312 G W Pontoon 4 714 100 E e Foxford 300 s Lough 200 400 500 600 B ACHILL t e Cullin SOUND r N26 466 G N n I 588 r Lough W R319 e N59 H a Feeagh P a t E y R319 N Buckoogh N58 W / 452 1 e Claggan Mountain B s Knockletragh t a e n r n g Beltra Mulranny o G Lough r European Destination of Excellence r T e r e a n i w l Ballycroy National Park Céide Fields a y R310 Furnace Lough 524 500 Dublin 400 R317 Corraun Hill 300 R312 St Brendens Rockfleet Burrishoole N5 200 Well Castle Abbey Newport Kildownet 100 3 Castle Church W R311 Achillbeg y a e Island s w t n e e r e n r W G Castlebar a n r y e t s R311 e W N59 MAYO t a Clew Bay e r N60 G 1 N5 GREENWAY WESTERN GREAT N84 Clare Island Westport ˜ Jutting proudly into the Atlantic Ocean, Mayo has a stunningly beautiful, unspoilt 7 R330 CO MAYO MAYO CO environment - a magical destination for visitors. -

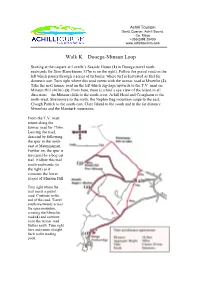

Walk K: the Dooega-Minaun Loop

Achill Tourism Davitt Quarter, Achill Sound, Co. Mayo +353(0)98 20400 www.achilltourism.com Walk K – Dooega-Minaun Loop Starting at the carpark at Lavelle’s Seaside House (1) in Dooega travel north- eastwards for 2km (Knockmore 337m is on the right). Follow the gravel road on the left which passes through a series of turbaries, where turf is harvested as fuel for domestic use. Turn right where this road meets with the tarmac road at Mweelin (2). Take the next tarmac road on the left which zig-zags upwards to the T.V. mast on Minaun Hill (403m) (3). From here, there is a bird’s eye view of the island in all directions – the Minaun cliffs to the south-west, Achill Head and Croaghaun to the north-west, Slievemore to the north, the Nephin Beg mountain range to the east, Croagh Patrick to the south-east, Clare Island to the south and in the far distance Mweelrea and the Mamturk mountains. From the T.V. mast return along the tarmac road for 750m. Leaving the road, descend by following the spur to the north- east at Maumnaman. Further on, the spur is traversed by a bog cut trail. Follow this trail south-eastwards (to the right) as it contours the lower slopes of Minaun Hill. Turn right where the trail meets a gravel road. Continue to the end of the road. Travel south-westwards across the open mountain, crossing the Mweelin road (4) and continue on to the tarmac road further south. Turn right here and return straight back to the starting point. -

Newport Draft Town Design Statement

NEWPORT DRAFT TOWN DESIGN STATEMENT CONTENTS SECTION 1 1. INTRODUCTION 2. APPROACHING NEWPORT- FIRST IMPRESSIONS 3. TOWNS CENTRE- NEWPORTS PUBLIC REALM 4. THE WATERS EDGE- NEWPORTS GREATEST ASSET 5. GETTING AROUND BY FOOT AND BICYCLE 6. BUILT HERITAGE -PAST AND FUTURE 7. UPGRADING BUILDINGS TO ADDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE 8. MAP OF NEWPORT PROPOSALS 9. REFERENCES SECTION 2 NEWPORT HISTORY AND CHARACTER (BY LOTTS ARCHITECTURAL AND URBANISM LTD) IMPORTANT NOTE ALL ILLUSTRATIONS IN THIS DOCUMENT ARE FOR THE PURPOSE OF GIVING A GENERAL IMPRESSION ONLY. DETAILS WITHIN THE DRAWING SHOULD NOT BE TAKEN AS BEING FINAL. ALL SUGGESTED PUBLIC REALM AND BUILDING DESIGN WOULD BE SUBJECT TO STATUTORY PLANNING APPROVALS AND OTHER COMPLIANCES. SECTION 1 1. INTRODUCTION Newport is a truly unique place. Its superb and dramatic natural setting, its river, bridges, church and fine Main street make a visit to Newport unforgettable. It is different from all other Irish towns. As Newport continues to evolve it is important to ensure that this unique character is preserved and enhanced, and that new development and future growth is suitable and harmonious with this character. This Town Design Statement sets out to present a vision making the most of Newport’s many strengths, addressing its weaknesses and ensuring that its future growth is of the highest and most suitable quality. This document presents a plan of action to create a sustainable and vibrant town where; • people want to live, visit, work, invest in and do business. • safety allows people choose to walk and cycle rather than drive. • the natural and built heritage is appreciated, preserved and enjoyed fully. -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered.