PREVENTING YOUTH VIOLENCE and DROPOUT: a RANDOMIZED FIELD EXPERIMENT Sara Heller Harold A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benchmark Presentation Description

ANALYT ICS ™ TRENDS IN POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY: Everything a Municipality Should Know and Ask Their Police Department In this session Ron Huberman will review a variety of new police accountability models being used around the country, as well as assessments of their effectiveness. Additionally, he will cover what is considered to be the 101’s of accountability that should be in place in every police department. Finally, Ron will provide a few case studies of what went right and what went wrong with recent highly publicized police shootings and other use-of-force incidents – and the aftermaths of those events. As police liability settlements continue to grow year after year, these new accountability systems aren’t just ‘nice-to-haves’, they are ‘must-haves’ for cities to demonstrate systematic approaches for the monitoring and intervention of problematic patterns of police officer conduct. Ron Huberman BIO Ron Huberman is currently CEO and Co-Founder of Benchmark Analytics, a police force management and early intervention software solution provider that’s dedicated to advancing officer career paths and overall department goals. During his 16-year career in Chicago city government, Ron helped tackle many of the challenges municipal governments face in a variety of positions, including: • Nine years in the Chicago Police Department — advancing to Assistant Deputy Superintendent, where he created the country’s most advanced policing technology system and developed innovative, community-based strategies that helped decrease crime. • Executive Director of the Chicago Office of Emergency Management and Communications — where Ron created the state-of-the-art Operations ANALYT ICS ™ Center, which provides real-time intelligence to public safety and homeland security officials. -

2021 Proxy Statement

1811 E. Northrop Blvd. Chandler, Arizona 85286 NOTICE OF 2021 ANNUAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS To the Stockholders of Zovio Inc: Notice is hereby given that the 2021 Annual Meeting of Stockholders (the “Annual Meeting”) of Zovio Inc, a Delaware corporation, will be held on Wednesday, May 19, 2021 at 9:00 a.m., Pacific Time, for the following purposes: 1. To elect three Class III directors, Teresa S. Carroll, Ryan D. Craig and Kirsten M. Marriner, for a three-year term to expire at the 2024 Annual Meeting of Stockholders; 2. To ratify the appointment of Deloitte & Touche LLP as our independent registered public accounting firm for the year ending December 31, 2021; 3. To approve on an advisory, non-binding basis the compensation of our named executive officers as presented in the proxy statement accompanying this notice; and 4. To transact such other business as may be properly brought before the Annual Meeting or any adjournment thereof. The Annual Meeting will be a completely virtual meeting of stockholders. To participate, vote or submit questions during the Annual Meeting via live webcast, please visit www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/ZVO2021. You will not be able to attend the Annual Meeting in person. We have also elected to provide access to our proxy materials over the internet under the Securities and Exchange Commission’s “notice and access” rules. We believe these rules allow us to provide you with the information you need while reducing our delivery costs and the environmental impact of the Annual Meeting. Our Board of Directors has fixed the close of business on March 26, 2021 as the record date for the determination of stockholders entitled to notice of, and to vote at, the Annual Meeting and at any adjournment or postponement thereof. -

Monday, May 17, 2021 Session Time: 11:00 AM - 12:00 PM

** New sessions and activities continually being added. Check back for updates. Schedule subject to change. ** 4/23/2021 10:42 AM Monday, May 17, 2021 Session Time: 11:00 AM - 12:00 PM Opening & Welcome • Dan Mahoney, LEIT Section Chair / Deputy Director, NCRIC • Cynthia Renaud, President, IACP Keynote • Catherine De Bolle, Executive Director, Europol Presentation of Scanlon Excellence in Criminal Justice Information Sharing Award Session Time: 12:15 AM - 1:00 PM Achieving CJIS Compliance with Smartphones - What You Need to Know • Chris Weatherly CISSP-ISSMP - Information Security Officer, FBI • Eric Wood - Director, Automated Regional Justice Information System (ARJIS) • Dale Stockton - Managing Partner, Public Safety Insight Smartphones provide operational benefits that can be significantly expanded if officers can access criminal justice databases. This requires compliance with CJIS policy and can be somewhat challenging. The workshop will provide clear guidance on key areas including multi-factor authentication, mobile device management, encryption requirements, and compensating control options. Presenters include an agency IT manager who achieved approval for CJI query on department smartphones, a veteran FBI CJIS ISO, and a practitioner who authored a guide to achieving CJIS compliance with smartphones. Connecting Technology Infrastructure and Operational Requirements • Mike Bell - Chief Technology Officer, Houuston Police Department • Crystal Cody CGCIO - Public Safety Technology Director, City of Charlotte Innovation and Technology • Christian Quinn - Senior Director of Government Affairs, Brooks Bawden Moore • Richard Zak - Director, Public Safety & Justice Solutions, Microsoft 1 This session will focus on the connection between technology infrastructure and operational requirements - and include the critical role of cyber security, the growing complexity of digital evidence management, and the challenge of managing the security and compliance of information across law enforcement and social service agencies for incidents. -

The Bigger Scandal

TEACHING AND TRUTH The Bigger Scandal Pauline Lipman A story in the Chicago Tribune by reporter Azam Ahmed revealed that when Secretary of Education Arne Duncan was head of Chicago Public Schools (CPS), he maintained a confidential list of influential people seeking help in getting par- ticular children into the best schools. Amy Goodman and Juan González exam- ined this story on their radio program Democracy Now! via interviews with Azam Ahmed, teacher and educational activist Jitu Brown, and Pauline Lip- man, professor of educational policy studies and director of the Collaborative for Equity and Justice in Education. Lipman pointed out that the controversy over the VIP list hid an even greater scandal: the undermining of democratic public education by the growth of two-tiered educational systems in cities such as Chi- cago. The article below is taken from her remarks on that broadcast. he larger scandal is that Chicago has basically a two-tiered education sys- tem. While a handful of selective enrollment magnet schools, or boutique Tschools, have been set up in gentrifying and affluent neighborhoods under the Renaissance 2010 initiative, and charter schools in African American and Latino communities, there has been a simultaneous disinvestment in neighbor- hood schools. Parents across the city are scrambling to try to get their kids into a few good schools. Instead of creating quality public schools in every neighbor- hood, CPS has created this two-tiered system. And under Renaissance 2010, CPS is closing down neighborhood schools and replacing them with charter schools and a privatized education system. They are firing or laying off certified teachers, dismantling locally elected school councils, and creating a market of public education in Chicago. -

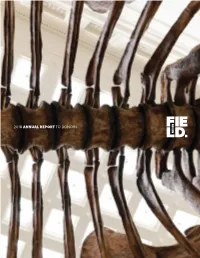

2018 ANNUAL REPORT to DONORS on the Cover: a Close-Up of Máximo’S Massive Skeletal Frame

2018 ANNUAL REPORT TO DONORS On the cover: A close-up of Máximo’s massive skeletal frame. His placement in the renovated Stanley Field Hall invites guests to get up-close and personal. Visitors can walk under the titanosaur’s massive legs and sit at his feet. 2 Griffin Dinosaur Experience 4 Native North America Hall 6 Because Earth. The Campaign for the Field Museum 8 Science 16 Engagement 24 Honor Roll Contents 2 Field Museum Dear Friends, In its historic 125th anniversary year, the Field Museum achieved a new level of accomplishment in science, public engagement, and philanthropy. We are grateful to all donors and members for championing our mission to fuel a journey of discovery across time to enable solutions for a brighter future rich in nature and culture. In September 2018, the Museum’s Board of Trustees launched the public phase of an ambitious fundraising initiative. Because Earth. The Campaign for the Field Museum will raise $250 million dollars for our scientific enterprises, exhibitions, programs, and endowment. Our dedication to Earth’s future is strengthened by a new mission and brand that reinforce our commitment to global scientific leadership. Over the past six years, the Museum has transformed more than 25 percent of its public spaces, culminating in 2018 with renovations of Stanley Field Hall and the unveiling of the Griffin Dinosaur Experience. We are deeply grateful to the Kenneth C. Griffin Charitable Fund for an extraordinary commitment to dinosaur programs at the Field. In 2018, we also announced a three-year renovation of the Native North America Hall and unveiled the Rice Native Gardens with a land dedication ceremony in October. -

Chicago, Illinois | Grade: C (11Th of 26 Cities)

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS | Grade: C (11th of 26 cities) How reform-friendly is Chicago? HUMAN FINANCIAL CHARTER QUALITY DISTRICT MUNICIpaL CATEGORY CapITAL CapITAL ENVIRONMENT CONTROL ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT Rank 6 of 26 16 of 25 23 of 24 17 of 25 7 of 26 1 of 25 Overview Which American cities are most hospitable to education reform, especially the “entrepreneurial” kind? To answer this question for Chicago and other cities examined in this study, we used publicly available data, national and local surveys, and interviews conducted with on-the-ground insiders. Respondents provided information about the city environment as a whole as well as the Chicago Public Schools.1 Judgments based upon these data, however, are the responsibility of the authors. Note, too, that due to the study’s timing, any major policy changes that cities (or states) may have made in connection with the Race to the Top competition are not captured in these rankings (but see sidebar for partial update). Background Chicago’s longstanding and abysmal achievement and graduation rates have catalyzed education reform—especially via the municipal sector—for more than a decade. But it’s still an uphill battle, with challenges such as school violence hindering gains on key performance indicators. (In June 2010, the city announced a $25 million initiative to combat school violence.) Since 1995, Chicago’s schools have been under mayoral control—and under the same mayor, Richard Daley (elected in 1989). In 2004, Daley launched “Renaissance 2010,” an initiative to shut the city’s worst schools and replace them with Race to the Top Update: Illinois—Chicago new higher-quality charter and district Illinois applied for round 1 of Race to the Top funding. -

The 2012 Chicago Teachers Union Strike

The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies Volume 74 Article 4 Number 2 Volume 74 No. 2 (2013) June 2013 Striking Back Against Corporate Education Reform: The 2012 hicC ago Teachers Union Strike Kurt Hilgendorf Chicago Teachers Union Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Elementary Education Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Pre-Elementary, Early Childhood, Kindergarten Teacher Education Commons Recommended Citation Hilgendorf, Kurt (2013) "Striking Back Against Corporate Education Reform: The 2012 hicaC go Teachers Union Strike," The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies: Vol. 74 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor/vol74/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ouncC ilor: A Journal of the Social Studies by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hilgendorf: Striking Back Against Corporate Education Reform: The 2012 Chicag Striking Back Against Corporate Education Reform: The 2012 Chicago Teachers Union Strike Kurt Hilgendorf Chicago Teachers Union Soon after the Chicago Teachers Union’s (CTU) House of Delegates voted to suspend the union’s seven-day September 2012 strike, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel blanketed local television airwaves with $1 million in paid advertising funded by Democrats for Education Reform, a New York-based “Astroturf” organization heavily financed by hedge fund operators. In the ad, Emanuel claims that though negotiations were difficult, “more accountability is the right deal for our kids.”1 Aside from being a mild nuisance to primetime TV viewers, the commercial became a conversation piece among Chicago residents. -

2018 Annual Report

2018 Mikva Challenge Annual Report 2 mikvachallenge.org These are groundbreaking times for Mikva Challenge. During the past year, we widened our reach and served a record number of youth in Action Civics programs in Illinois, Washington, DC, and California, fostering pathways to greater participation of young people in our democratic fabric. This year we celebrate with pride Mikva’s 20th anniversary. We look forward to an even stronger future, ever guided by the principle central to our founders, Abner and Zoe Mikva: the best way to learn democracy is to do democracy. Students involved in Mikva Challenge are demonstrating that they want to be at the table; they want to have a say. As you will see in this Annual Report, we are one of the few programs in the country that is shifting students’ civic attitudes and skills and showing that young people can engage thoughtfully and responsibly in our democratic process. Further, we have found the consequences for young people to be transformative – to their sense of identity, their motivation to serve one’s community, their academic and social lives, and their development of active, informed citizenship and leadership. Yet, far too few students have access to this kind of learning, particularly in under-resourced communities of color. This year we officially launched the Mikva Challenge National Strategy: focused efforts to expand Mikva’s Action Civics curricula and programs to youth in localities with limited opportunities. This kind of involvement in civic affairs always has been fundamental to promoting a just and equitable society. The deep rifts rocking this nation remind us that making space for informed dialogue and thoughtful participation is just as important today. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION DARREYL YOUNG-GIBSON, Plaintiff, V. B

Case: 1:11-cv-08982 Document #: 81 Filed: 08/29/13 Page 1 of 26 PageID #:<pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION ) DARREYL YOUNG-GIBSON, ) ) Plaintiff, ) v. ) No. 11 C 8982 ) BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY ) Judge Virginia M. Kendall OF CHICAGO, ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Plaintiff Darreyl Young-Gibson filed suit against Defendant Board of Education of the City of Chicago (the “Board”) pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended by 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. Young-Gibson is the former principal of Percy Julian High School (“Julian”) and was terminated from her position in October 2009. Young-Gibson alleges the Board terminated her employment because of her race and gender (Count I), and retaliated against her for writing a letter rescinding the suspension of a Julian employee, allegedly to oppose discrimination. (Count II). The Board moves for summary judgment on both counts. For the reasons stated herein, the Board’s Motion for Summary Judgment is granted. STATEMENT OF MATERIAL UNDISPUTED FACTS1 Young-Gibson was hired by the Board of Education of the City of Chicago as a substitute teacher in 1972. (Complaint, Dkt. No. 1, p.7). In January 2008, Young-Gibson became 1 Throughout this Opinion, the Court refers to the Parties’ Local Rule 56.1 Statements of Undisputed Material Facts as follows: citations to the Board’s Statement of Undisputed Facts (Dkt. No. 35) have been abbreviated to “Def. 56.1 St. ¶ __”; citations to Young-Gibson’s Amended Response to Defendant’s Statement of Undisputed Fact (Dkt. -

Nues Herald-Spectator

Your local source since 1951. - One Dollar I Thursday, November 1, 2012I A W*PP(RTScompanyI A CHICAGO SUN-TIMESpublication nilesheraldspectator.COm Nues Herald-Spectator Go George Wendt stars in Odd Couple' [Page 46] Food Pulling for pork [Page 41] Members of the ocal Gujarati community celebrate the Hindu festival of Navratri with a garba, a traditional Read the full story [Page 5] Idance, Oct. 27 at the Feldman Recreation Center in Niles. JEFF KRAGE-for Sun-T/mes Media Mommy Apps for busy moms and Honoring goodness their families [Page 40] Nues Herald-Spectator I © 2012 Sun-Times Media I All Rights Reserved vertìse in t 12 H:OL1DK IFT GUUJJ SOC..TLQ911 S:r1in Tffl11 3YiUfld is Ol)IVO h 0969 Di1Iflds- ¿9C00000 sEr:1j.Nid3j L)1}U ?.00OOO N1V 6T03 LLOcJççj Ad space séadiine: Monday, Nov. 5 Publishes: Wednesday, No Contact your account executive TODAY! 2 THURSDA"( NO\ 'ER 1, 2012 NIL THE BOLD LOOK OFKOHLER 2012 MARI Award Winning Kitchen Oesgned and Built by Airoom Award-Winning Custom Kitchens We've designed and built over 14,000 projects, so chancesare your neighbors have worked with us. From traditional to contemporary, we feature Kohler's entire line of kitchen products and stand behindeach of our award-winning kitchens and custom home additions with our unmatched 15-year warranty. See your neighborhood at airoom.com AIROOM ¶ ARCHITECTS BUILDERS REMODELERS Free Consultation call 888.349.1 714 SINCE 1958 airoom.com Home Additions Kitchens Custom Homes J Master Spas J J Lower Leve's Home Theatres J Visit Our State-Of-the-Art Design Showrooms: Lincolnwood- 6825 North Lincoln Avenue, Naperville - 2764 West Aurora Avenue NIL THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 2012 3 BANNER KITCHEN & BATH SHOWROOM WINS IISHOWROOMOF THE YEAR!" -JJeL'orative Piunibing & Hardware Association, 2011 WETOT PROUDLY C THE NATION'S #1 KITCHEN AND BATH SHowRooM IS IN BUFFALO GROVE! SORRY NEW YORK, LA AND MIAMI- THE NORTHSHORE IS WHERE IT'S AT! Interactive displays Beautifully designed 15,000 sq. -

Portfolio School Districts Project

Portfolio School Districts Project Portfolio School Districts for Big Cities: An Interim Report Paul Hill, Christine Campbell, David Menefee-Libey, Brianna Dusseault, Michael DeArmond, Betheny Gross October 2009 Portfolio School Districts for Big Cities: An Interim Report OCTOBER 2009 AUTHORS: Paul Hill, Christine Campbell, David Menefee-Libey, Brianna Dusseault, Michael DeArmond, Betheny Gross Center on Reinventing Public Education University of Washington Bothell 2101 N. 34th Street, Suite 195 Seattle, Washington 98103-9158 www.crpe.org i About the Center on Reinventing Public Education The Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) was founded in 1993 at the University of Washington. CRPE engages in independent research and policy analysis on a range of K–12 public education reform issues, including finance & productivity, human resources, governance, regulation, leadership, school choice, equity, and effectiveness. CRPE’s work is based on two premises: that public schools should be measured against the goal of educating all children well, and that current institutions too often fail to achieve this goal. Our research uses evidence from the field and lessons learned from other sectors to understand complicated problems and to design innovative and practical solutions for policymakers, elected officials, parents, educators, and community leaders. This report was made possible by grants from Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Joyce Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author(s). -

The 1995 Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act and the Cps Ceo: a Historical Examination of the Adminstration of Ceos Paul Vallas and Arne Duncan

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 The 1995 Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act and the Cps Ceo: A Historical Examination of the Adminstration of Ceos Paul Vallas and Arne Duncan Leviis Haney Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Haney, Leviis, "The 1995 Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act and the Cps Ceo: A Historical Examination of the Adminstration of Ceos Paul Vallas and Arne Duncan" (2011). Dissertations. 62. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/62 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Leviis Haney LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE 1995 CHICAGO SCHOOL REFORM AMENDATORY ACT AND THE CPS CEO: A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF THE ADMINISTRATION OF CEOS PAUL VALLAS AND ARNE DUNCAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION PROGRAM IN EDUCATIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND SUPERVISION BY LEVIIS A. HANEY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2011 Copyright by LeViis A. Haney, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my mom, Leark A. Haney, for providing me such a great foundation by which to grow personally, professionally and educationally, passing along the gift of your intellect, and teaching me what true leadership is all about.