The ''End of the Gods'' in Late Roman Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London In this paper I turn my attention to the changes that took place in London in the mid to late second century. Until recently the prevailing orthodoxy amongst students of Roman London was that the settlement suffered a major population decline in this period. Recent excavations have shown that not all properties were blighted by abandonment or neglect, and this has encouraged some to suggest that the evidence for decline may have been exaggerated.1 Here I wish to restate the case for a significant decline in housing density in the period circa AD 160, but also draw attention to evidence for this being a period of increased investment in the architecture of religion and ceremony. New discoveries of temple complexes have considerably improved our ability to describe London’s evolving ritual landscape. This evidence allows for the speculative reconstruction of the main processional routes through the city. It also shows that the main investment in ceremonial architecture took place at the very time that London’s population was entering a period of rapid decline. We are therefore faced with two puzzling developments: why were parts of London emptied of houses in the middle second century, and why was this contraction accompanied by increased spending on religious architecture? This apparent contradiction merits detailed consideration. The causes of the changes of this period have been much debated, with most emphasis given to the economic and political factors that reduced London’s importance in late antiquity. These arguments remain valid, but here I wish to return to the suggestion that the Antonine plague, also known as the plague of Galen, may have been instrumental in setting London on its new trajectory.2 The possible demographic and economic consequences of this plague have been much debated in the pages of this journal, with a conservative view of its impact generally prevailing. -

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation The Mari Lwyd and the Horse Queen: Palimpsests of Ancient ideas A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Celtic Studies 2012 Lyle Tompsen 1 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Abstract The idea of a horse as a deity of the land, sovereignty and fertility can be seen in many cultures with Indo-European roots. The earliest and most complete reference to this deity can be seen in Vedic texts from 1500 BCE. Documentary evidence in rock art, and sixth century BCE Tartessian inscriptions demonstrate that the ancient Celtic world saw this deity of the land as a Horse Queen that ruled the land and granted fertility. Evidence suggests that she could grant sovereignty rights to humans by uniting with them (literally or symbolically), through ingestion, or intercourse. The Horse Queen is represented, or alluded to in such divergent areas as Bronze Age English hill figures, Celtic coinage, Roman horse deities, mediaeval and modern Celtic masked traditions. Even modern Welsh traditions, such as the Mari Lwyd, infer her existence and confirm the value of her symbolism in the modern world. 2 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Table of Contents List of definitions: ............................................................................................................ 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

Names-In-Myfarog1.Pdf

Names Mythic Fantasy Role-playing Game Below is a list of common Jarlaætt and Þulaætt first Hâvamâl stanza 43 names in Þulê. Most of the masculine names can be turned into feminine names by adding a feminine “Vin sînum ending or by exchanging the masculine (-us, -i et cetera) ending with a feminine ending. E. g. Axius skal maðr vinr vera, becomes Axia and Ailill becomes Aililla. Players with religious characters can come up with a name for their þeim ok þess vin; character's father and then add “-son” or “-dôttir” (“daughter”) to find his or her surname. Players with en ôvinir sîns traditional characters can come up with a name for their character's mother and then add “-son” or “- skyli engi maðr dôttir” to find his or her surname. vinar vinr vera.” The common name combination in Þulê includes: First Name+Surname+(af) Tribe name+(auk) Nationality. (You shall be friend E. g.; Rhemaxa (a woman) Acciusdôttir (her father's with your friend name+dôttir, so we know she is religious) af Zumi (her and his friends; but no man shall ever tribe) auk Tawia (her nationality). (“Af” means “of” be friend and “auk” means “and”.) It is in Þulê expected from with the friend of an enemy.) everyone that when they meet strangers they first of all introduce themselves with their full name. Jarlaætt & Þulaætt Ailill (-a) Annius (-a) Atilius (-a) From A to Æ Ainstulfus (-a) Ansprandus (-a) Atreus (-a) Aburius (-a) Airgetmar (-a) Api (♀ ) Atrius (-a) Acamas (-a) Alahisus (-a) Appuleius (-a) Atrius (-a) Accius (-a) Alalius (-a) Aquillius (-a) Atronius (-a) Acilius -

Jegens Dè Godin Nehalennia Heeft Placidus

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/26513 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-01 and may be subject to change. I BERICHT UIT BRITANNIA In 1976 is in Engeland te York(-Clementhorpe), het Romeinse Eboracum, een stuk gevonden van een plaat van grove zandsteen (“gritstone”), dat secundair gebruikt is in een na-middeleeuwse kalkoven. Van de plaat ís het rechter bovengedeelte bewaard gebleven; dit is 63 x 49 x 14 cm groot. Op de voorzijde zijn nog sporen te zien van een tabula ansata, alsmede een gedeelte van een bijzonder interessante Latijnse inscriptie (pl. 25 A). De vondst is onlangs door dr. R. S.O. Tomlin bekendgemaakt in het aan Romeins Engeland gewijde tijdschrift Britannia, jg. 8, 1977, 430 v., nr. 18. De nieuwste epigrafische aanwinst uit York bevat het eerste gegeven uit Britannia dat rechtstreeks in verband kan worden gebracht met de cultus van Nehalennia in het mondingsgebied van de Schelde. Het belang daarvan is zodanig dat het gerechtvaardigd lijkt er ook in een Nederlands archeologisch tijdschrift de aandacht op te vestigen. Het opschrift luidt: [------]* etg eRio 'LOci / [------Jg g -l -vFdvcivs / [------ ]cidvs-dom o / [--------] VEL10CAS[S] IVM 5/ [--------]eG0TIAT0R / [--------]RCVM ET FANVM / [--------] D'[.] GRATO ET / [--------. Voor de aanvulling van deze tekst kan allereerst gebruik worden gemaakt van het onderste gedeelte van een kalkstenen altaar dat op donderdag 3 september 1970 uit de Oosterschelde is opgevist in het gebied van de gemeente Zierikzee, dicht bij Colijnsplaat (pl. -

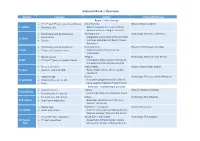

Suburani Book 1 Overview

Suburani Book 1 Overview Chapter Language Culture History/Mythology Roma – life in the city • 1st, 2nd and 3rd pers. sg., present tense Life in the city History: Rome in AD 64 1: Subūrai • Reading Latin Subura; Population of city of Rome; Women at work; Living in an insula • Nominative and accusative sg. Building Rome Mythology: Romulus and Remus • Declensions Geography and growth of Rome; Public 2: Rōma • Gender buildings and spaces of Rome; Forum Romanum • Nominative and accusative pl. Entertainment History: Three phases of ruling 3: lūdī • 3rd pers. pl., present tense Public festivals; Chariot-racing; Charioteers • Neuter nouns Religion Mythology: Deucalion and Pyrrha 4: deī • 1st and 2nd pers. pl., present tense Christianity; State religion; Homes of the gods; Sacrifice; Private worship • Present infinitive Public health History: Rome under attack! 5: aqua • possum, volō and nōlō Baths; Public toilets; Water supply; Sanitation • Ablative case Slavery Mythology: Theseus and the Minotaur 6: servitium • Prepositions + acc./+ abl. How were people enslaved? Life of a • Time slave; Seeking freedom; Manumission Britannia – establishing a province • Imperfect tense London History: Romans invading 7: Londīnium • Perfect tense (-v- stems) Londinium; Made in Londinium; Food • Perfect tense (all stems) Britain Mythology: The Amazons 8: Britannia • Superlative adjectives Britannia; Camulodunum; Resist or accept? The Druids • Dative case Rebellion – hard power History: Resistance 9: rebelliō • Verbs with dative Chain of command; Competing forces; Women and war; Why join the army? • 1st and 2nd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis – soft power Mythology: The Gorgons 10: Aquae • 3rd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis; Different gods; Curses; Sūlis Military life; People of Roman Britain Gaul and Lusitania – life in a province • Genitive case The sea History: Pirates in the Mediterranean Sea • -ne and -que Romans and the sea; Underwater 11: mare archaeology; Navigation and maps; Dangers at sea • Imperatives (inc. -

Aquae Sulis. the Origins and Development of a Roman Town

7 AQUAE SULIS. THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF A ROMAN TOWN Peter Davenport Ideas about Roman Bath - Aquae Sulis - based on excavation work in the town in the early 1990s were briefly summarised in part of the article I wrote in Bath History Vol.V, in 1994: 'Roman Bath and its Hinterland'. Further studies and excavations in Walcot and the centre of town have since largely confirmed what was said then, but have also added details and raised some interesting new questions. Recent discoveries in other parts of the town have also contributed their portion. In what follows I want to expand my study of the evidence from recent excavations and the implications arising from them. The basic theme of this paper is the site and character of the settlement at Aquae Sulis and its origins. It has always been assumed that the hot springs have been the main and constant factor in the origins of Bath and the development of the town around them. While it would be foolish to deny this completely, the creation of the town seems to be a more complex process and to owe much to other factors. Before considering this we ought to ask, in more general terms, how might a town begin? With certain exceptions, there was nothing in Britain before the Roman conquest of AD43 that we, or perhaps the Romans, would recognise as a town. Celtic Britain was a deeply rural society. The status of hill forts, considered as towns or not as academic fashion changes, is highly debatable, but they probably acted as central places, where trade and social relationships were articulated or carried on in an organized way. -

Sample File Table of Contents Chapter 1: Overview of Extrico Tabula

Sample file Table of Contents Chapter 1: Overview of Extrico Tabula..................................5 Celtic Culture............................................................. 49 Professions ........................................................................6 Celtic Women............................................................ 49 New Professions...........................................................6 Celtic Language......................................................... 49 Profession Summary for Cthulhu Invictus ...................6 Britannia Names ........................................................ 50 The Random Roman Name Generator...............................8 The Boudican Uprising.............................................. 51 Chapter 2: A Brief Guide To The Province Of Germania.....17 Religion, Druids, Bards................................................... 53 Germania Timeline.....................................................18 Druids ........................................................................ 53 Military Forces...........................................................18 Bards.......................................................................... 53 Economy ....................................................................19 Druidic and Bardic Magic in Cthulhu Invictus.......... 53 Native Peoples............................................................19 Celtic Religion........................................................... 53 Germanic Names........................................................20 -

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A)

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A) David K. Faux The goal of the present work is to assemble widely scattered facts to accurately record the story of one of Europe’s most enigmatic people of the early historic era – the Cimbri. To meet this goal, the present study will trace the antecedents and descendants of the Cimbri, who reside or resided in the northern part of the Jutland Peninsula, in what is today known as the County of Himmerland, Denmark. It is likely that the name Cimbri came to represent the peoples of the Cimbric Peninsula and nearby islands, now called Jutland, Fyn and so on. Very early (3rd Century BC) Greek sources also make note of the Teutones, a tribe closely associated with the Cimbri, however their specific place of residence is not precisely located. It is not until the 1st Century AD that Roman commentators describe other tribes residing within this geographical area. At some point before 500 AD, there is no further mention of the Cimbri or Teutones in any source, and the Cimbric Cheronese (Peninsula) is then called Jutland. As we shall see, problems in accomplishing this task are somewhat daunting. For example, there are inconsistencies in datasources, and highly conflicting viewpoints expressed by those interpreting the data. These difficulties can be addressed by a careful sifting of diverse material that has come to light largely due to the storehouse of primary source information accessed by the power of the Internet. Historical, archaeological and genetic data will be integrated to lift the veil that has to date obscured the story of the Cimbri, or Cimbrian, peoples. -

The Political, Practical and Personal Roles of Religion in Roman Britain

2009 Pages 41-47 Undergraduate Section – 2nd Place Julian Barr Between Society and Spirit: The Political, Practical and Personal Roles of Religion in Roman Britain ABSTRACT Conquering imperial powers often use religion to control indigenous populations. I argue that religion served this purpose in Roman Britain, while simultaneously fulfilling Britons’ practical and spiritual requirements. Rome’s State and Imperial Cults were overt instruments of social control, fostering awareness of Britain’s subjugation and sanctifying Roman rule. Yet Roman and Celtic polytheism coalesced to allow considerable religious freedom outside the official Cults’ bounds. Thus Romano-British religion benefited not only society, but also the individual. BBBIOGRAPHYBIOGRAPHY Julian Barr is an Honours student in Ancient History. He completed his BA in 2008, with Majors in History and Ancient History. Primarily his undergraduate degree focussed upon Australian history, as well as Greek and Roman studies with a strong component in Classical languages. 41 BETWEEN SOCIETY AND SPIRIT : THE POLITICAL , PRACTICAL AND PERSONAL ROLES OF RELIGION IN ROMAN BRITAIN Religion in Roman Britain simultaneously served the practical and spiritual needs of its people while also strengthening Roman rule. Comparatively speaking, the Druids had been far more overt than Rome in using religion to exert power. Yet it should be noted that this opinion is of itself the result of Rome’s manipulation of religion to politically sully the Druids’ name. The State and Imperial Cults represent Rome’s clearest employment of religion to control the Romano-British. However even within this sphere of influence there lay potential for spiritual fulfilment. For a variety of reasons, the State and Imperial Cults likely held little sway over the Romano-British. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the House of Nodens by Sam Gafford ISBN 13: 9781626412545

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The House of Nodens by Sam Gafford ISBN 13: 9781626412545. In 1975, young Bill Simmons is the new kid in New Milford. Bullied and struggling for acceptance, he meets four other boys who form the ‘the Cemetery League’, a group devoted to the weird, exotic and bizarre in movies, comics and television. Each boy carries their own secrets which combine to come to a violent and fiery conclusion in a lonely Connecticut forest. Now, nearly forty years later, the events of that night come back to haunt Bill Simmons as, one by one, the members of the Cemetery League are targeted by an unknown force that may have unnatural links to their past. Has something, or someone, come to exact a bloody vengeance? And how is it linked to a serial killer’s twenty year spree throughout the Nutmeg State? To answer these questions, Bill Simmons will have to face his greatest fears and the failure that destroyed his life and left him a hopeless alcoholic. But will it be enough? "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. Sam Gafford is published in a wide variety of anthologies and publications. His fiction has appeared in collections such as Black Wings Volumes I, III and V, as well as Flesh Like Smoke, The Lemon Herberts, Wicked Tales, and in magazines like Weird Fiction Review, Dark Corridor, Nameless, and others. A lifelong Lovecraftian, he has written critical articles appearing in Lovecraft Studies, Crypt of Cthulhu, Weird Fiction Review, Nameless, and more. An expert on the life and work of pioneering science fiction writer William Hope Hodgson, Gafford is currently working on a book-length critical biography of Hodgson. -

![The Social and Cultural Implications of Curse Tablets [Defixiones] in Britain and on the Continent](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3392/the-social-and-cultural-implications-of-curse-tablets-defixiones-in-britain-and-on-the-continent-1783392.webp)

The Social and Cultural Implications of Curse Tablets [Defixiones] in Britain and on the Continent

THE SOCIAL AND CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS OF CURSE TABLETS [DEFIXIONES] IN BRITAIN AND ON THE CONTINENT Geoff W. Adams Abstract The central theme of this study is to analyse the idiosyncratic nature of the Romano-British interpreta- tion of the use of defixiones and various ‘prayers for justice’. The prevalence of revenge as a theme within this comparatively isolated Roman province is notable and clearly illustrates the regional inter- pretation that affected the implementation of this religious tradition. The Romano-British curse tablets were largely reactionary, seeking either justice or revenge for a previous wrong, which in turn affected the motivation that led to their production. This regional interpretation was quite different to their overall use on the continent, but even these examples frequently also exhibit some degree of local inter- pretation by their issuers. When approaching this topic, owing to the vast number of curse tablets and other religious inscriptions discovered throughout Europe there will naturally have to be some omissions from this discussion. The term defixio has enough problems in itself, with there being some debate concerning the formula and distinction in this term,1 which is why the title refers to other religious inscriptions. The nature of this discus- sion is to focus upon the social and cultural context of curse tablets, so there will be no discussion of the precise literary formulas used in these tablets. While discussing these curse tablets as a whole, I shall also have to limit the focus to two main temple precincts in Britain as well, namely being Bath and Uley. The purpose is to examine the curse tablets from these places within the wider social and cultural contexts in Europe, to attempt to find regional variations and uses for these tablets. -

Some Remarks on the Latin Curse Tablets from Pannonia1

Acta Ant. Hung. 59, 2019, 561–574 DOI: 10.1556/068.2019.59.1–4.49 ANDREA BARTA SOME REMARKS ON THE LATIN CURSE TABLETS 1 FROM PANNONIA Summary: This paper gives a short review of the research from recent years on texts of Latin curse tab- lets from Pannonia. In the last decade, four new lead tablets of quite long and well-readable texts came to light in well documented archeaological context in Pannonia. On one hand, these findings have not only doubled the small corpus, but they presented new data from both the field of magic and linguistics. On the other, in connection with the examination of the new pieces, the reconsideration of earlier ones could not be delayed any longer. Keywords: curse tablet, defixio, Latin linguistics, vulgar Latin, Pannonia 1. INTRODUCTION For more than one hundred years, curse tablets have been representing one of the main direct sources of Vulgar Latin. Besides being essential for scholars in field of ancient magic and religion, these small sheets of metal usually containing a unique and ‘hand-made’ text may contribute to the results what linguists can obtain from the much more formulaic and even once checked and proved stone inscriptions. In the past few years new pieces were found in Pannonia,2 the grown number of these objects can now deservedly be considered as a source for linguistical research – 1 The present paper was prepared within the framework of the project NKFIH (National Research, Development and Innovation Office) No. K 124170 entitled “Computerized Historical Linguistic Data- base of Latin Inscriptions of the Imperial Age” (http://lldb.elte.hu/) and of the project entitled “Lendület (‘Momentum’) Research Group for Computational Latin Dialectology” (Research Institute for Linguis- tics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences).