Not All of the District of Columbia Marketplace's Internal Controls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DC Will Become Third in the Nation to Adopt a Health Insurance Requirement for 2019 by Jodi Kwarciany

JUNE 28, 2018 DC Will Become Third in the Nation to Adopt a Health Insurance Requirement for 2019 By Jodi Kwarciany On Tuesday, the DC Council voted in the Budget Support Act for fiscal year (FY) 2019 to add the District to the list of jurisdictions, like Massachusetts and New Jersey, that are implementing a local health insurance requirement for 2019.1 This local “individual mandate” will help protect DC’s coverage gains, maintain insurance market stability, and protect the District from harmful federal changes, and should be signed into law by the Mayor. The new requirement follows the repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) “individual mandate,” or requirement that all individuals obtain health insurance or pay a penalty, in December’s federal tax bill. This policy change, along with other recent federal actions, jeopardizes the District’s private insurance market and health coverage gains, potentially causing insurance premiums in the District to rise by nearly 14 percent for ACA-compliant plans, and increasing the number of District residents who go without any health coverage. Through a local health insurance requirement, the District can maintain the protections of the federal law and support the health of DC residents. The District’s new requirement largely mirrors that of the previous federal requirement while including stronger protections for many residents. As the federal requirement ends after 2018, beginning in 2019 most DC residents will be required to maintain minimum essential coverage (MEC), or health insurance that is ACA-compliant. This covers most forms of insurance like employer-based coverage, health plans sold on DC Health Link, Medicare, and Medicaid. -

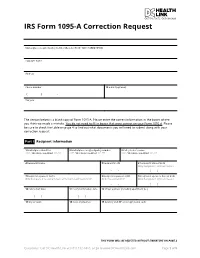

IRS Form 1095-A Correction Request

IRS Form 1095-A Correction Request Marketplace-assigned policy number (Box 2 of Form 1095-A) (REQUIRED): Taxpayer name Address Phone number 12 E-mail (optional) ( ) - Tax year The section below is a blank copy of Form 1095-A. Please enter the correct information in the boxes where you think we made a mistake. You do not need to fill in boxes that were correct on your Form 1095-A. Please be sure to check the table on page 4 to find out what documents you will need to submit along with your correction request. Part I Recipient Information 1 Marketplace identifier 2 Marketplace-assigned policy number 3 Policy issuer’s name ***** OFFICIAL USE ONLY ****** ***** OFFICIAL USE ONLY ****** ***** OFFICIAL USE ONLY ****** 4 Recipient’s name 5 Recipient’s SSN 6 Recipient’s date of birth Only Complete if SSN not Present - - / / 7 Recipient’s spouse’s name 8 Recipient’s spouse’s SSN 9 Recipient’s spouse’s date of birth Only Complete if receiving Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC) Only if receiving APTC Only Complete if SSN not Present - - / / 10 Policy start date 11 Policy termination date 12 Street address (including apartment no.) / / / / 13 City or town 14 State or province 15 Country and ZIP or foreign postal code THIS FORM WILL BE REJECTED WITHOUT SIGNATURE ON PAGE 3 Questions? Call DC Health Link at (855) 532-5465, or go to www.DCHealthLink.com Page 1 of 5 IRS Form 1095-A Correction Request Part II Covered Individuals A. Covered Individual Name B. Covered Individual C. Covered Individual D. -

Health Insurance Marketplace

TAX YEAR 2021 Health Care Reform Health Insurance Marketplace Norman M. Golden, EA 1900 South Norfolk Street, Suite 218 San Mateo, CA 94403-1172 (650) 212-1040 [email protected] Health Insurance Marketplace • Mental health and substance use disorder services, in- cluding behavioral health treatment (this includes coun- The Health Insurance Marketplace helps uninsured people seling and psychotherapy). find health coverage. When you fill out the Marketplace ap- • Prescription drugs. plication online the website will tell you if you qualify for: • Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices (ser- • Private health insurance plans. The site will tell you vices and devices to help people with injuries, disabili- whether you qualify for lower costs based on your house- ties, or chronic conditions gain or recover mental and hold size and income. Plans cover essential health ben- physical skills). efits, pre-existing conditions, and preventive care. If you • Laboratory services. do not qualify for lower costs, you can still use the Mar- • Preventive and wellness services and chronic disease ketplace to buy insurance at the standard price. management. • Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Pro- • Pediatric services, including oral and vision care. gram (CHIP). These programs provide coverage to mil- lions of families with limited income. If it looks like you Essential health benefits are minimum requirements for all qualify, the exchange will share information with your Marketplace plans. Specific services covered in each broad state agency and they’ll contact you. Many but not all benefit category can vary based on your state’s require- states have expanded Medicaid to cover more people. -

Consumer Decisionmaking in the Health Care Marketplace

Research Report Consumer Decisionmaking in the Health Care Marketplace Erin Audrey Taylor, Katherine Grace Carman, Andrea Lopez, Ashley N. Muchow, Parisa Roshan, Christine Eibner C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr1567 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9505-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface For this report, researchers conducted a literature review to better understand how consumers make choices about health insurance enrollment and to assess how website design can influence choice when consumers select plans online. -

Application for Health Coverage Apply Faster Online at Dchealthlink.Com

Form Approved Application for Health Coverage OMB No. 0938-1191 Who can use this Anyone who needs health coverage can use this application. application? If someone is helping you fill out this application, you may need to complete Appendix C. Apply faster Apply faster online at DCHealthLink.com. online What happens Send your complete, signed application to the address on page 4. If you don’t have all the information we ask for, sign and submit your next? application anyway. We’ll follow up with you within 1–2 weeks to let you know how to join a health plan. If you don’t hear from us, visit DCHealthLink.com or call 1-855-532-5465. Filling out this application doesn’t mean you have to buy health coverage. Get help with You need to use a different application to get help with costs. You could qualify for: costs • A new tax credit that can immediately help pay your premiums for health coverage THINGS TO KNOW • Free or low-cost coverage from Medicaid You may qualify for a free or low-cost program even if you earn as much as $94,000 a year (for a family of 4). Visit DCHealthLink.com or call 1-855-532-5465 to learn more. Get help with • Online: DCHealthLink.com. this application • Phone: Call our Customer Service Center at 1-855-532-5465. • In person: There may be counselors in your area who can help. Visit DCHealthLink.com or call 1-855-532-5465 for more information. • En Español: Llame a nuestro centro de ayuda al cliente gratis al 1-855-532-5465. -

DC STANDARD IAP PAPER APPLICATION (ENGLISH)-(Sept

Form Approved OMB No. 0938-1191 Standard Application for Health Coverage & Help Paying Costs Use this application • Affordable private health insurance plans that offer comprehensive coverage to help you stay well to see what • A new tax credit that can immediately help pay your premiums for coverage you health coverage qualify for • Free or low-cost insurance from Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) You may qualify for a free or low-cost program even if you earn as much as $94,000 a year (for a family of 4). Who can use this • Use this application to apply for anyone in your family. • Apply even if you or your child already has health coverage. You could application? be eligible for lower-cost or free coverage. • Families that include immigrants can apply. You can apply for your child even if you aren’t eligible for coverage. Applying won’t affect your immigration status or chances of becoming a permanent resident or citizen. • If someone is helping you fill out this application, you may need to complete Appendix C. Apply faster Apply faster online at DCHealthLink.com. online What you may • Social Security numbers (or document numbers for any eligible immigrants who need insurance) need to apply • Employer and income information for everyone in your family (for example, from paystubs, W-2 forms, or wage and tax statements) THINGS TO KNOW • Policy numbers for any current health insurance • Information about any job-related health insurance available to your family Why do we ask for We ask about income and other information to let you know what coverage you qualify for and if you can get any help paying for it. -

Q1. Please Provide a Current Organizational Chart for the District of Columbia Health Benefit Exchange Authority (HBX), and Include

Q1. Please provide a current organizational chart for the District of Columbia Health Benefit Exchange Authority (HBX), and include: a. The number of full time equivalents (FTEs) at each organizational level; See Attachment A. b. A list of all FY15 FTEs broken down by program and activity; See Attachment B. c. The employee responsible for the management of each program and activity; Program Activity Responsible Responsible Manager Employee Agency Fiscal Accounting Kara Onorato, Chief Samuel Ince, Operations Operations Financial Officer Accounting Operations Provides comprehensive Budget Operations Jilu Lenji, Budget and efficient financial Operations management services, to and on behalf of District Agencies so that the financial integrity of the District of Columbia is maintained. This program is standard for all agencies using performance-based budgeting. Agency Management Contracts and Ikeita Cantú Hinojosa, Nicole Matthews, Procurement Chief Operating Interim Contracting Provides for Officer Officer administrative support Information Candace Walls, and the required tools Technology Services Information to achieve operational Technology Specialist and programmatic results. This program Personnel Troy Higginbotham, is standard for all Management Liaison agencies using Specialist performance-based Facilities Paulette Saunders, management. Management Administrative Officer Performance Management Debra Curtis, Senior Debra Curtis, Senior Deputy Director for Deputy Director for Policy and Programs Policy and Programs Legal Services Purvee -

Autism Spectrum Disorders Toolkit for Pediatric Primary Care Providers in the District of Columbia Overview and Primer

Autism Spectrum Disorders Toolkit for Pediatric Primary Care Providers in the District of Columbia Overview and Primer DC Collaborative for Mental Health in Pediatric Primary Care Washington, DC Summer 2020 Version 1.1 Page | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The DC Collaborative for Mental Health in Pediatric Primary Care (the DC Collaborative) is a local public- private partnership dedicated to improving the integration of mental health in pediatric primary care for children in the District of Columbia. This toolkit focuses specifically on supporting children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and their families, by providing primary care providers with the tools to help families navigate the developmental disabilities landscape in Washington, DC. Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 MCHAT ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnostic Evaluation ................................................................................................................................... 9 Referral Algorithm ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Early Intervention and -

Health Insurance Exchange Operations Chart

Health Insurance Exchange Operations Chart *Chart updated June 12, 2015 Allison Wils As states continue to refine the operations of their health insurance exchanges, regardless of the exchange type (state-based exchange, state partnership exchange, or federally facilitated marketplace), it's helpful to compare and contrast operational resources. This chart contains each state's resources and forms for three distinct, and fundamentally important, areas of exchange operation: applications, appeals, and taxes. With links directly to the states' forms and guides related to these issue areas, this chart serves as a one-stop resource library for those interested in developing new, or revising old, versions of applications, appeals, and tax resources. Like all State Refor(u)m research, this chart is a collaborative effort with you, the user. Know of something we should add to this compilation? Your feedback is central to our ongoing, real-time analytical process, so tell us in a comment, or email [email protected] with your suggestions. State Application Forms & Guides Appeal Forms & Guides Tax Guides IRS: Form 1095-A Health Insurance Marketplace Statement IRS: Instructions for Form 1095-A Health Insurance Marketplace Statement IRS: Form 8962 Premium Tax Credit IRS: Form 8965 Health Coverage Federally-Facilitated Marketplaces Healthcare.gov: Appeal Request Exemptions Healthcare.gov: Application for (FFM) & State Partnership Form for Wyoming Marketplace (SPM) States (AK, Health Coverage & Help Paying IRS: Instructions for Form 8965 AL, AR, AZ, DE, FL, GA, IA, IL, IN, Costs Healthcare.gov: Appeal Request Health Coverage Exemptions KS, LA, ME, MI, MS, MO, MT, NC, Form for Select States (Group 1) Healthcare.gov: Instructions to IRS: Affordable Care Act Tax ND, NE, NH, NJ, OH, OK, PA, SC, Help You Complete Your Provisions SD, TN, TX, UT, VA, WA, WV, and Healthcare.gov: Appeal Request Application for Health Coverage Form for Select States (Group 2) WY) IRS: Pub. -

Position Name Salary Executive Director (HBX) Kofman,Mila 228362 Management Liaison Specialist Higginbotham,Troy M

FY18-19 HBX Performance Oversight: Attachment A Schedule A: Staff as of 2.6.2019 Position Name Salary Executive Director (HBX) Kofman,Mila 228362 Management Liaison Specialist Higginbotham,Troy M. 126423 Contract Specialist Matthews,Nicole F 129646 Senior Deputy Director Curtis,Debra Scott 212383 Case Manager Burman,Elizabeth 76199 Agency Chief Financial Officer Edmonds,Marjorie V 172170 Accounting Officer Ince,Samuel 140083 Budget Officer Lenji,Jilu 140083 Contract Officer White,Annie R 149242 Contract Specialist Tilahuan, Helen 96065 Director of Information System Sparks,Jason 169146 Supervisory Attorney Advisor Alonso,Alexander O 175044 Case Manager Holloway,Candice 73167 Case Manager James,Keeta 73167 Statistician Haines,Stephen R 129646 IT Specialist (Network) Walls,Candace M 101523 Program Analyst Smith,Cherie R 73167 General Counsel Kempf,Purvee P 211667 Program Analyst VACANT 100639 Case Manager Manuszak,Julie 59727 Program Analyst Wiggins,Maurice R 113531 IT Specialist (Applic. Software) VACANT 100639 IT Spec (Application Software) Liwanag,Andrew 101523 Public Information Officer Hudson,Adam 139322 Case Manager Anderson,India 61647 Case Manager Calderon,Amy 73906 Supervisory Attorney Advisor Libster,Jennifer M 178602 Communications and Civic Engag Wharton Boyd Linda 180544 Program Manager Taylor-Sutton,Kenneth L 139729 Community Outreach Specialist Green,Kimberly 92250 Deputy Director of Program Ser Bangit,Eliza Navarro 180544 Case Manager Beamon,Frankie 54325 Supervisory Attorney Advisor Senkewicz,Marybeth 184853 Customer Service -

Here's What You Need to Do

DC Health Link PO Box 44018 Washington, DC 20026 IVL_TAX YOUR 1095-A HEALTH COVERAGE TAX FORM This letter includes your tax Form 1095-A. You’re receiving this tax form because you or someone in your household enrolled in a private health insurance plan through DC Health Link in 2020. Federal law required most Americans to have a minimum level of health coverage or pay a tax penalty through 2018. The District of Columbia now has an individual responsibility requirement. This means that DC residents must have qualifying health coverage all year. If you don’t have coverage, and don’t qualify for an exemption, you’ll have to pay a penalty when you file your DC taxes. For more information: https://dchealthlink.com/individual-responsibility-requirement. We are required by federal law to send a copy of your Form 1095-A to you and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). You may need this form to complete your federal tax return for 2020. Please keep it for your records. You can also download a copy of your tax form at dchealthlink.com. Form 1095-A is also called the Health Insurance Marketplace Statement. It shows how long you or someone in your household had health insurance through DC Health Link last year. If you received an advanced premium tax credit, your Form 1095-A also shows how much of your tax credit was applied to your premium each month. Here’s What You Need to Do Now If you received an advanced premium tax credit in 2020, you must complete IRS Premium Tax Credit Form 8962 when you file your federal taxes. -

See How Easy Health Plan Enrollment Can Be Through the SHOP

A BETTER WAY TO TAKE CARE OF BUSINESS SMALL BUSINESS HEALTH OPTIONS PROGRAM (SHOP) I WASHINGTON, DC See how easy health plan enrollment can be through the SHOP Whether you’re a small business or a broker, you can simplify the application process by using DC Health Link, Washington, DC’s online SHOP portal. dchealthlink.com/smallbusiness A BETTER WAY TO TAKE CARE OF BUSINESS DC Health Link — the smart and convenient way for small businesses to offer health benefits What is the DC Health Link health insurance marketplace? DC Health Link is the District of Columbia’s online marketplace for small businesses to purchase health coverage. This online marketplace allows employers to easily compare, purchase, and enroll in any health plan offered by participating providers. Kaiser Permanente’s participation in every metal tier in DC Health Link ensures employers can offer their employees high-quality,* integrated care at an affordable price. What are the benefits of DC Health Link to small businesses? CHOICE AND FLEXIBILITY — By consolidating the buying power of small businesses, DC Health Link provides employers a wide selection of affordable health coverage options. Companies can choose one of three ways to offer coverage to their employees. They can offer: • One metal tier of coverage. This option, known as “employee choice,” allows employers to offer employees the greatest freedom to choose the plan that best fits their needs. At the same time, it allows employers to structure health benefits that meet their budget requirements. Each employee can select any health plan from any carrier within the metal tier selected by the employer.