Self-Defense - from the Wild West to 9/11: Who, What, When Amos N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

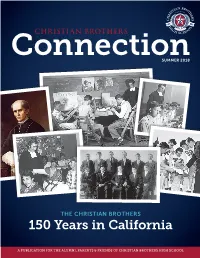

Connection – Summer 2018

ConnectionCHRISTIAN BROTHERS SUMMER 2018 THE CHRISTIAN BROTHERS 150 Years in California A PUBLICATION FOR THE ALUMNI, PARENTS & FRIENDS OF CHRISTIAN BROTHERS HIGH SCHOOL CB Leadership Team Lorcan P. Barnes President Chris Orr Principal June McBride Board of Trustees Director of Finance David Desmond ’94 The Board of Trustees at Christian Brothers High School is comprised of 11 volunteers Assistant Principal dedicated to safeguarding and advancing the school’s Lasallian Catholic college preparatory mission. Before joining the Board of Trustees, candidates undergo Michelle Williams training on Lasallian charism (history, spirituality and philosophy of education) and Assistant Principal Policy Governance, a model used by Lasallian schools throughout the District of Myra Makelim San Francisco New Orleans. In the 2017–18 school year, the board welcomed two new Human Resources Director members, Marianne Evashenk and Heidi Harrison. David Walrath serves in the role of chair and Mr. Stephen Mahaney ’69 is the vice chair. Kristen McCarthy Director of Admissions & The Policy Governance model comprises an inclusive, written set of goals for the school, Communications called Ends Policies, which guide the board in monitoring the performance of the school through the President/CEO. Ends Policies help ensure that Christian Brothers High Nancy Smith-Fagan School adheres to the vision of the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the District Director of Advancement of San Francisco New Orleans. “The Board thanks the families who have entrusted their children to our school,” says Chair David Walrath. “We are constantly amazed by our unbelievable students. They are creative, hardworking and committed to the Lasallian Core Principles. Assisting Connection is a publication of these students are the school’s faculty, staff and administration. -

1908 Journal

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

Claremen & Women in the Great War 1914-1918

Claremen & Women in The Great War 1914-1918 The following gives some of the Armies, Regiments and Corps that Claremen fought with in WW1, the battles and events they died in, those who became POW’s, those who had shell shock, some brothers who died, those shot at dawn, Clare politicians in WW1, Claremen courtmartialled, and the awards and medals won by Claremen and women. The people named below are those who partook in WW1 from Clare. They include those who died and those who survived. The names were mainly taken from the following records, books, websites and people: Peadar McNamara (PMcN), Keir McNamara, Tom Burnell’s Book ‘The Clare War Dead’ (TB), The In Flanders website, ‘The Men from North Clare’ Guss O’Halloran, findagrave website, ancestry.com, fold3.com, North Clare Soldiers in WW1 Website NCS, Joe O’Muircheartaigh, Brian Honan, Kilrush Men engaged in WW1 Website (KM), Dolores Murrihy, Eric Shaw, Claremen/Women who served in the Australian Imperial Forces during World War 1(AI), Claremen who served in the Canadian Forces in World War 1 (CI), British Army WWI Pension Records for Claremen in service. (Clare Library), Sharon Carberry, ‘Clare and the Great War’ by Joe Power, The Story of the RMF 1914-1918 by Martin Staunton, Booklet on Kilnasoolagh Church Newmarket on Fergus, Eddie Lough, Commonwealth War Grave Commission Burials in County Clare Graveyards (Clare Library), Mapping our Anzacs Website (MA), Kilkee Civic Trust KCT, Paddy Waldron, Daniel McCarthy’s Book ‘Ireland’s Banner County’ (DMC), The Clare Journal (CJ), The Saturday Record (SR), The Clare Champion, The Clare People, Charles E Glynn’s List of Kilrush Men in the Great War (C E Glynn), The nd 2 Munsters in France HS Jervis, The ‘History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers 1861 to 1922’ by Captain S. -

Fortlauderdale-Results-2021.Pdf

Fort Lauderdale, FL Hollywood Mini/Junior VIP List 1 Unchained SJ Dance Company 2 River Deep SJ Dance Company 3 Smile SJ Dance Company 4 Wonderful World SJ Dance Company 5 Avalanche Performance Edge Dance Complex 6 Bridge Over Troubled Water Performance Edge Dance Complex 7 Hero Performance Edge Dance Complex 8 Fashion Week SJ Dance Company 9 Alchemist Miami Dance Project 10 Hustle Performance Edge Dance Complex Hollywood Teen/Senior VIP List 1 Barren Miami Dance Project 2 Death Marked Love Miami Dance Project 3 Burn SJ Dance Company 4 2ko SJ Dance Company 5 Never Walk Alone SJ Dance Company 6 Empty Chairs Miami Dance Project 7 That's Life SJ Dance Company 8 Let It Be SJ Dance Company 9 The Heart You Think You Gave Me Miami Dance Project 10 Leave A Light On Dance Empire of Miami Best Hollywood Studio SJ Dance Company Broadway Mini/Junior VIP List 1 Bollywoods Party PILARES DANCE 2 Deluge Xpressit Dance Center 3 My Strongest Suit Dancing Inxs 4 Schoolyard Swag Dancing Inxs 5 Safari Xpressit Dance Center 6 Latin Spice Dancing Inxs 7 Arena Of Champion PILARES DANCE 8 Natural Living Art PILARES DANCE 9 Newest Wrinkle Xpressit Dance Center 10 Battlefield Dancing Inxs Broadway Teen/Senior VIP List 1 Resurrection Dancing Inxs 2 Reflection Miami Dance Project 3 Las Nenas Dancing Inxs 4 Miss Demeanor Dancing Inxs 5 Ashes Dancing Inxs 6 Work Like Nobody Else Miami Dance Project 7 Show Girls PILARES DANCE 8 In The Bullring Miami Dance Project 9 Miss You So Much PILARES DANCE 10 Forsake Me Miami Dance Project Best Broadway Studio Dancing Inxs IDOL -

Understanding & Dism Antling Privilege

Free Land: A Hip Hop Journey from the Streets of Oakland to the Wild Wild West Written and Performed by Ariel Luckey ©2009 Social Equity &Inclusion Equity Social Volume II, Issue I February, 2012 Abstract Free Land is a dynamic hip hop theater solo show written and performed by Ariel Luckey, directed by Margo Hall and scored by Ryan Luckey. The show follows a young white man’s search for his roots as it takes him from the streets of Oakland to the prairies of Wyoming on an atrix Center for the Advancement of the Advancement for Center atrix unforgettable journey into the heart of American history. During an interview with his grandfather he learns that their beloved family ranch was actually a Homestead, a free land grant from the government. Haunted by the past, he’s compell ed to dig deeper into the history of the land, only to come face to face with the legacy of theft and genocide in the Wild Wild West. Caught between the romantic cowboy tales of his childhood and the devastating reality of what he learns, he grapples with A program of the M the of program A . the contradictions in his own life and the possibility for justice and reconciliation. Free Land weaves spoken word poetry, acting, dance and hip hop music into a compelling performance that challenges us to take an unflinching look at the truth buried in the land beneath our feet. Ariel Luckey is a nationally acclaimed poet, actor, and playwright whose community and performance work dances in the crossroads of education, art, and activism. -

SPRING 2016 BANNER RECIPIENTS (Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Name)

SPRING 2016 BANNER RECIPIENTS (Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Name) Click on name to view biography. Render Crayton Page 2 John Downey Page 3 John Galvin Page 4 Jonathan S. Gibson Page 5 Irving T. Gumb Page 6 Thomas B. Hayward Page 7 R. G. Head Page 8 Landon Jones Page 9 Charles Keating, IV Page 10 Fred J. Lukomski Page 11 John McCants Page 12 Paul F. McCarthy Page 13 Andy Mills Page 14 J. Moorhouse Page 15 Harold “Nate” Murphy Page 16 Pete Oswald Page 17 John “Jimmy” Thach Page 18 Render Crayton_ ______________ Render Crayton Written by Kevin Vienna In early 1966, while flying a combat mission over North Vietnam, Captain Render Crayton’s A4E Skyhawk was struck by anti-aircraft fire. The plane suffered crippling damage, with a resulting fire and explosion. Unable to maintain flight, Captain Crayton ejected over enemy territory. What happened next, though, demonstrates his character and heroism. While enemy troops quickly closed on his position, a search and rescue helicopter with armed escort arrived to attempt a pick up. Despite repeated efforts to clear the area of hostile fire, they were unsuccessful, and fuel ran low. Aware of this, and despite the grave personal danger, Captain Crayton selflessly directed them to depart, leading to his inevitable capture by the enemy. So began seven years of captivity as a prisoner of war. During this period, Captain Crayton provided superb leadership and guidance to fellow prisoners at several POW locations. Under the most adverse conditions, he resisted his captor’s efforts to break him, and he helped others maintain their resistance. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-. Tuesday, April 30, 1991

April 30, 1991 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 9595 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-.Tuesday, April 30, 1991 The House met at 12 noon. around; the person to your left, the minute and to revise and extend his re The Chaplain, Rev. James David person to your right, they may very marks.) Ford, D.D., offered the following pray significantly be out of work in the very Mr. FROST. Mr. Speaker, during the er: near future. And remember, the person last Presidential campaign, there was a Gracious God, may we not express next to you is looking at you. refrain of "Where's George?" asking the attitudes of our hearts and minds And what is the answer of this ad where then-Vice President Bush was on only in words or speech, but in deeds ministration to this problem? Nothing. a variety of issues. and in truth. May our feelings of faith Where is the legislation to take care of Unfortunately for the country, that and hope and love find fulfillment in all those unemployed who have lost refrain rings very true today. charity and caring and in the deeds of their jobs where there is no unemploy Our President, George Bush, loved justice. Teach us always, 0 God, not ment compensation? There is not any. foreign policy and handled the Persian only to sing and say the words of What is the answer of this adminis Gulf situation well, but our President praise, but to be vigorous in our deeds tration to the problem of the recession is nowhere. to be found when it comes of mercy and kindness. -

For Pete's Sake

FINAL-1 Sat, Jan 27, 2018 5:25:50 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of February 4 - 10, 2018 For Pete’s sake Pete Holmes as seen in “Crashing” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 HBO’s “Crashing” is currently enjoying its sophomore season, with a new episode airing Sunday, Feb. 4. Writer, creator and star Pete Holmes (“Ugly Americans”) has drawn humor from some of his deepest memories and most personal life moments. He plays a fictionalized version of himself in the dark comedy — a character who struggles with the realities of adulthood, such as the disollution of his marriage and the difficulties of carving out a place for himself in the comedy world. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIESBay 4 YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA Group Page Shell We Need: SALES & SERVICE Motorsports WINTER ALLERGIES ARE HERE! 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Are you suffering from itchy eyes, sneezing, sinusitis We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC or asthma?Alleviate your mold allergies this season. Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 at 527 So. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 7, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Magnum P.I

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 7, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Magnum P.I. ’ 48 Hours ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS “Perennial” ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 2020 Tokyo Olympics Marathon, Track and Field, Diving, Basketball. (N) (Live) News 2020 Tokyo Olympics 5 52020 Tokyo Olympics Marathon, Track and Field, Diving, Basketball. (N) (Live) News 2020 Tokyo Olympics 6 6Boxing PBC: Cody Crowley vs. Gabriel Maestre. FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Funniest Home Videos Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9Friends ’ Friends ’ Friends Friends Weekend News WGN News Potash Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Father Brown ’ Agatha Christie’s Poirot Death in Paradise ’ Austin City Limits ’ Doctor Who “Nightmare of Eden” Burt Wolf Father 11 Father Brown ’ Death in Paradise ’ Shakespeare Professor T Unforgotten Downton Abbey on Masterpiece ’ 12 12 Funniest Home Videos Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Smile 24 24 Heartland ’ Murdoch Mysteries ’ Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Boxing PBC: Cody Crowley vs. -

The Naming of Gaming

The Naming of Gaming Pauliina Raento Academy of Finland and William A. Douglass University of Nevada, Reno The naming of casinos in Las Vegas, Nevada, is an essential ingredient in the design of the city's entertainment landscape. More than 300 names have been used in the naming of gaming in Las Vegas since 1955. They occur in seven dominant patterns: 1) luck and good fortune, 2) wealth and opulence, 3) action, adventure, excitement and fantasy, 4) geography, 5) a certain moment, era, or season, 6) intimacy and informal- ity, and 7) "power words" commonly used in the naming of businesses. The categories are described and analyzed from the perspective of the evolution of Las Vegas. Regional variations between the Las Vegas Strip, Downtown Las Vegas, and suburban Las Vegas are also discussed. The names provide a powerful means of evoking senses of place, images, and identities for the casinos. They underscore the interpretative subjectivity and plurality of the relationship between people and commercial urban environments. Introduction We name people, things, and places to distinguish them from one another and to give them character. Often the names are commemorative and draw upon features (usually positive) of individuals and places. Buildings, streets and towns are named after other familiar places, historical events, and distinguished persons who have played a notable role in the shared past. As an example of the latter, over one quarter of the roughly 3,000 counties in the United States are named patriotically, most often commemorating a political figure (Zelinsky 1983, 6). Names of streets and buildings in capital cities and other centers of importance have special prestige.