A Historic Saga of Settlement and Nation Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workers' Hill Powder Yard Eleutherian Mills, the Du

VISITOR SERVICES WORKERS’ HILL ELEUTHERIAN MILLS, THE Where the du Pont story begins. Open daily from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. The last bus for a DU PONT FAMILY HOME tour of the du Pont residence leaves at 3:30 p.m. Tickets Workers’ Hill is the remains of one of purchased after 2 p.m. are valid for the following day. several workers’ communities built by Eleutherian Mills, the first du Pont Closed on Thanksgiving and Christmas. the DuPont Company within walking home in America, was named for distance of the powder yards. its owner, Eleuthère Irénée du Pont. From January through mid-March, guided tours are He acquired the sixty-five-acre site The Gibbons House reflects the lives of the powder yard at 10:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. weekdays, with weekend in 1802 to build a gunpowder manufactory. The home foremen and their families. hours 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. today has furnishings and decorative arts that belonged Visitors with special needs should inquire at the Visitor The Brandywine Manufacturers’ Sunday School to his family and the generations that followed. Center concerning available services. illustrates early nineteenth-century education where E. I. du Pont’s restored French Garden is the beginning workers’ children learned to read and write. Contact any staff member for first aid assistance. of the du Pont family garden tradition in the The Belin House, where three generations of company Brandywine Valley. Several self-guided special tour leaflets are available at bookkeepers lived, is now the Belin House Organic Café. -

Recommendations for a Circa 1870-1885 Worker's Vegetable

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A CIRCA 1870-1885 WORKER'S VEGETABLE GARDEN AT THE HAGLEY MUSEUM by Karen Marie Probst A non-thesis project submitted to the Fa~ulty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Horticultural Administration December 1987 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A CIRCA 1870-1885 WORKER'S VEGETABLE GARDEN AT THE HAGLEY MUSEUM by Karen Marie Probst Approved: QpffM.1J tJ ~ 1iftLJt i ames E. Swasey, Ph.D. Professor In Charge Of on-Thesis Projects On Behalf Of The Advisory Committee Approved: ames E. Swasey, Ph.D. Coordinator of the Longw d Graduate Program in Public Horticulture Administration Approved: Richard B. Murray, Ph.D. Associate Provost for Graduate Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS page Project 1 Chapter 1 • INTRODUCTION. • • • • . • . • • • • • . • • . • . • . • • • • • • . • . 1 Footnotes. .. 11 2. RECOMMENDED VEGETABLES •••••.••••••••••.•••.••. 12 ASPARAGUS. • • • • • . • • . • • • . • • . • • . .• • 12 Footnotes. .. 16 BEAN. • • • . • • . • . • . .. 18 Footnotes . .-.. .. 34 BEET. • • . • . • • • . • • . • . • . • . • • • . .. 38 Footnotes........................... 46 CABBAGE. • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • .. 48 Footnotes. .. 61 CARROT. • • • • • • . • • . • • . • • • . • • . • . • • . .. 64 Footnotes. .. 70 CELERY. • • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • • • . .. 72 Footnotes. .. 79 CORN. • . • • . • • • • • • • . • • • • . • . • • • • • • . • . .• 81 Footnotes. .. 87 CUCUMBER. • • . • . • . • • • • • • . • . • . .. 89 Footnotes. .. 94 LETTUCE. -

The Water Supply Still Proved Inadequate for the Growing City

From Creek to Tap: Creek to Tap: From From Creek to Tap The Brandywine and Wilmington’s Public Water System The Brandywine and Wilmington’s Public Water System The Brandywine and Wilmington’s FromFrom CreekCreek toto TapTap The Brandywine and Wilmington’s Public Water System Wilmington City of Douglas C. McVarish Timothy J. Mancl Richard Meyer From Creek to Tap The Story of Wilmington's Public Water System From Creek to Tap The Story of Wilmington’s Public Water System Douglas C. McVarish Timothy J. Mancl Richard Meyer City of Wilmington, Delaware Brandywine Plant from the air, 1929. Copyright © 2014 by City of Wilmington, Delaware All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part by any means without permission of the publisher is strictly prohibited. City of Wilmington, Delaware Contents Louis L. Redding – City/County Building 800 French Street Wilmington, DE 19801 7 Introduction 10 Milestones 17 Historical Sketch prepared by 64 From Creek to Tap 93 Notes John Milner Associates, Inc. 97 Credits 535 North Church Street West Chester, PA 19380 Douglas C. McVarish, Historian Timothy J. Mancl, Industrial Archeologist Richard Meyer, Editor Sarah J. Ruch, Graphic Designer Robert E. Schultz, Illustrator printed in the United States of America by The Standard Group 433 Pearl Street Reading, PA 19603 Introduction The City of Wilmington could not exist, let alone grow and thrive, without an adequate and readily accessible source of fresh water. True enough, but you may not have given the subject all that much thought. The intent of this book is to give you pause—how did your public water system come about; how has it grown and changed over the years; and how does it continue to deliver this most vital commodity to every home, school, and business in the city? We begin with a timeline that highlights some of the more important events in the history of the system, then move on to an illustrated historical sketch that provides background and context for these events. -

Sussex County

501 ALLOWANCES AND APPROPRIATIONS. Dolls. Ct,. Amount brought forward, 3,3137 58 To Lowder T. Layton, for damages on new road, 15 00 Albert Webster, do do 05 Appropriation for opening and making said road, 20 00 William K. Lockwood, commissioner on road, 2 days, 2 00 Albert Webster, do 3 3 00 T. L. Davis, do 3 3 00 George Jones, do 2 2 00 William Nickerson, do 2 2 00 Alexander Johnson, surveyor, 7 00 John Cox, for damages on road, 50 00 William Slay, do 06 David Marvel, do 06 Martha Day, do 06 Appropriation to open and make said road, 150 00 $3,642 31 March Session. Thomas S. Buckmaster, for overwork under a resolu- tion, 3 89 Isaac L. Crouch, for work on jail, 87 Joshua Nickerson, for work on a bridge, 2 08 S. C. Leatherberry, cryer of the courts, 20 62 Joab Fox, for work on a bridge, 9 87 James Jones, assessor for Duck Creek hundred, 29 38 Nathan Soward, Little Creek " 25 56 William Slaughter, Dover, " 27 56 John Sherwood, Murderkill, " 34 02 John Quillen, Milford, " 26 46 Henry W. Harrington, Mispillion, " 27 00 Dr. Isaac Jump, for medicine for prisoners in jail, 4 50 William Hirons, commissioner on road, 1 00 Thomas Stevenson, justice peace, for fees, 15 35 Alexander J. Taylor, late sheriff, board of prisoners and fees, 352 51 James B. Richardson, coroner, for fees, 17 23 John P. Coombe, justice of the peace, for fees, I 00 George Smith, commissioner oo new road, 1 00 Joho Ha wk ins, for excess of tax, for the years 1848-9, 12 98 John Sherwood, for services dividing school districts, I 00 Am,unt carried forward, $4,356 19 502 ALLOWANCES AND APPROPRIATIONS. -

An Analysis of the City of Wilmington

COMMUNITY ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILES – A TOOL FOR MEETING ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE GOALS: An Analysis of the City of Wilmington Researchers: Amy Roe Vernese Inniss Marcos Luna Emery Graham Dick Bosire Maragia Scott Smizik Sangeetha Sriram Kamala Dorsner Supervised by: John Byrne, Director Gerard Alleng, Policy Fellow Yda Schreuder, Senior Policy Fellow and Associate Professor of Geography Center for Energy and Environmental Policy College of Human Services, Education and Public Policy University of Delaware for the Science, Engineering &Technology Services Program a program supported by the Delaware General Assembly and the University of Delaware October 2003 Community Environmental Profiles: A Tool for Meeting Environmental Justice Goals – An Analysis of The City of Wilmington Researchers: Amy Roe Vernese Inniss Marcos Luna Emery Graham Dick Bosire Maragia Scott Smizik Sangeetha Sriram Kamala Dorsner Supervised by: John Byrne, Director Gerard Alleng, Policy Fellow Yda Schreuder, Senior Policy Fellow Center for Energy and Environmental Policy College of Human Services, Education and Public Policy University of Delaware for the Science, Engineering & Technology Services Program a program supported by the Delaware General Assembly and the University of Delaware October 2003 Preface It is a pleasure to present you with this report of the 2002 Science, Engineering & Technology (SET) Services Program. The report is designed to provide the Delaware General Assembly and the citizens of this State with an environmental profile that encompasses social, economic and environmental conditions in the City of Wilmington. CEEP received valuable assistance in preparing this report from many individuals in academia, state and local government. We owe our debt to Sally Wasileski, analytical chemist, and Terra Dassau, atmospheric chemist, both PhD. -

Exploiting Yeast Diversity to Produce Renewable Chemicals from Rice Straw and Husk

Exploiting yeast diversity to produce renewable chemicals from rice straw and husk Jia Wu 100030434 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to The University of East Anglia 2018 Quadram Institute Bioscience Norwich Research Park, Norwich, NR4 7UA ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with Current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Declaration Exploiting yeast diversity to produce renewable chemicals from rice straw and husk I certify that the work contained in this thesis is entirely the result of my own work, except where due reference is made to other authors as part of a joint piece of work. It has not previously been submitted in any form to the University of East Anglia or any other University. Jia Wu Abstract Exploiting organic lignocellulosic wastes via bio-refining processes has been widely accepted as one of the renewable, environmentally friendly solutions to producing platform chemicals and liquid fuels. Pre-treatment serves as an initial step to improve the accessibility of lignocellulosic polysaccharides to enzymes, and fermentation is a core step to obtain a range of products from the sugars. However, inhibitors of enzymatic saccharification and fermentation are unavoidably generated during hydrothermal pre-treatment. Therefore, the aim of this study has been to assess the associations and possibly correlations between severities of pre-treatment, yield of fermentable sugars and formation of inhibitors, and to evaluate the potential of 11 yeast diverse yeast strains for the potential to produce not only ethanol but also some highly- sought-after platform chemicals. -

Kalmar Nyckel: Using a 17Th Century Dutch Pinnace to Teach Physics and More DTI 2016-2017 Ancient Inventions

Kalmar Nyckel: Using a 17th century Dutch Pinnace to Teach Physics and More DTI 2016-2017 Ancient Inventions Terri Eros Challenges H.B. duPont Middle School, while located in a very suburban setting, serves a very diverse population. There are approximately 900 students in grades 6-8, with students almost evenly split between urban and suburban backgrounds. The academic readiness also varies greatly with relation to reading and math skills. It is not unusual to have a range of students reading all the way from a pre-primer level to those comfortable with high school text. In some cases the disparity is due to limited English proficiency. The math skills are similarly distributed with some students needing calculators for 2-digit addition while others are comfortable solving algebraic equations. To better meet student needs, our school piloted having honors classes in Science and Social Studies last year. Groupings were based on reading level for Social Studies and Math level for Science. The outcome was less than ideal for Science. At the middle school level, language skills are more important so that is now the basis of grouping for the 2016-2017 school year. In addition, our school is aiming for full inclusion. Students include those that have severe physical and/or emotional needs that interfere with their ability to interact linguistically, through either speech or writing. Despite these limitations, there is still an interest and an expectation to succeed in the Science classroom. The challenge is to incorporate the rigor of the Next Generation Science Standards, with its emphasis on student driven learning, while finding multiple access points for the students based on readiness. -

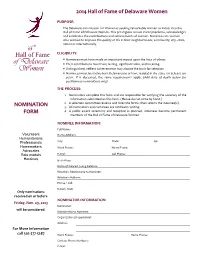

Nomination Form

2014 Hall of Fame of Delaware Women PURPOSE: The Delaware Commission for Women is seeking remarkable women to induct into the Hall of Fame of Delaware Women. This prestigious annual event proclaims, acknowledges and celebrates the contributions and achievements of women. Nominees are women who worked to improve the quality of life in their neighborhoods, community, city, state, nation or internationally. rd 33 ELIGIBILITY: Hall of Fame Nominees must have made an important impact upon the lives of others. of Delaware Their contributions must have lasting, significant value and meaning. Women Distinguished, selfless achievements may also be the basis for selection. Nominees must be native-born Delawareans or have resided in the state for at least ten years. If is deceased, the same requirements apply. (Add date of death below for posthumous nominations only) THE PROCESS: 1. Nominators complete this form and are responsible for verifying the accuracy of the information submitted on this form. (Please do not write by hand.) 2. A selection committee reviews and rates the forms, then selects the inductee(s). NOMINATION 3. All nominators and nominees are notified in writing. FORM 4. A public award ceremony and reception is planned, inductees become permanent members of the Hall of Fame of Delaware Women. NOMINEE INFORMATION: Full Name: Volunteers Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ Humanitarians Professionals City: State:_ Zip: Homemakers Work Phone: _________________ Home Phone: Advocates Role models E-mail:______________________ Cell Phone: _ Heroines Birth Place:________________ _ Name of Nearest Living Relative: Relative’s Relationship to Nominee: Relative’s Address: Phone / Cell: E-mail/ Web: Only nominations received on or before NOMINATOR INFORMATION: Friday, Nov. -

Kalmar Nyckel – a Guide to the Ship and Her History

Kalmar Nyckel – A Guide to the Ship and Her History Kalmar Nyckel – A Guide to the Ship and Her History 2 Guide to the Re‐creation of the Tall Ship KALMAR NYCKEL “Become Something Great” America’s original promise and enduring challenge. Excerpt from a letter by Peter Minuit to Swedish Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna As navigation makes kingdoms and countries thrive and in the WestIndies [North America] many places gradually come to be occupied by the English, Dutch, and French, I think the Swedish Crown ought not to stand back and refrain from having her name spread widely, also in foreign countries; and to that end I the undersigned, wish to offer my services to the Swedish The Kalmar Nyckel Foundation Crown to set out modestly on what might, by God’s Written & Compiled By grace, become something great within a short Samuel Heed, Esq. time [emphasis added]. With Captain Lauren Morgens & Alistair Gillanders, Esq. Firstly, I have suggested to Mr. Pieter Spiering [Spiring, Swedish Ambassador to the Hague] to make a journey to the Virginias, New Netherland and other places, in which regions certain places are well known to me, with a very good climate, which could be named Nova Sweediae [New Sweden]…. Your Excellency’s faithful servant, Cover photograph: The present day Kalmar Nyckel cruising on the Pieter Minuit Patuxent river on the Chesapeake during a visit to Solomon’s Island, MD in 2008. Photographer – Alistair Gillanders. Amsterdam, 15 June 1636 Copyright ©2009 Kalmar Nyckel Foundation. All rights reserved. Ship and History Guide – Version 1.01 Kalmar Nyckel – A Guide to the Ship and Her History 3 Table of Contents 7.1.3 The Main Deck and Its Features: .............................................. -

Van Rensselaer Family

.^^yVk. 929.2 V35204S ': 1715769 ^ REYNOLDS HISTORICAL '^^ GENEALOGY COLLECTION X W ® "^ iiX-i|i '€ -^ # V^t;j^ .^P> 3^"^V # © *j^; '^) * ^ 1 '^x '^ I It • i^© O ajKp -^^^ .a||^ .v^^ ^^^ ^^ wMj^ %^ ^o "V ^W 'K w ^- *P ^ • ^ ALLEN -^ COUNTY PUBLIC LIBR, W:^ lllillllli 3 1833 01436 9166 f% ^' J\ ^' ^% ^" ^%V> jil^ V^^ -llr.^ ^%V A^ '^' W* ^"^ '^" ^ ^' ?^% # "^ iir ^M^ V- r^ %f-^ ^ w ^ '9'A JC 4^' ^ V^ fel^ W' -^3- '^ ^^-' ^ ^' ^^ w^ ^3^ iK^ •rHnviDJ, ^l/OL American Historical Magazine VOL 2 JANUARY. I907. NO. I ' THE VAN RENSSELAER FAMILY. BY W. W. SPOONER. the early Dutch colonial families the Van OF Rensselaers were the first to acquire a great landed estate in America under the "patroon" system; they were among the first, after the English conquest of New Netherland, to have their possessions erected into a "manor," antedating the Livingstons and Van Cortlandts in this particular; and they were the last to relinquish their ancient prescriptive rights and to part with their hereditary demesnes under the altered social and political conditions of modem times. So far as an aristocracy, in the strict understanding of the term, may be said to have existed under American institu- tions—and it is an undoubted historical fact that a quite formal aristocratic society obtained throughout the colonial period and for some time subsequently, especially in New York, — the Van Rensselaers represented alike its highest attained privileges, its most elevated organization, and its most dignified expression. They were, in the first place, nobles in the old country, which cannot be said of any of the other manorial families of New York, although several of these claimed gentle descent. -

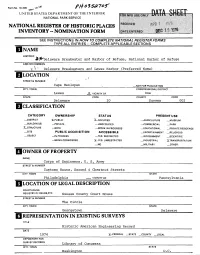

UCLA SSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 ^ -\0-' W1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ ,NAME HISTORIC . .^ il-T^belaware Breakwater and Harbor of Refuge, National Harbor of Refuge AND/OR COMMON Y \k> Delaware Breakwaters and Lewes Harbor (Preferred Name) ________ LOCATION STREETS. NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Lewes X VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 Sussex 002 UCLA SSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK X_STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -X-TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army STREET & NUMBER Customs House, Second & Chestnut Streets CITY, TOWN STATE Philadelphia VICINITY OF Pennsylvania LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Sussex County Court House STREET & NUMBER The Circle CITY, TOWN STATE Georgetown Delaware REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Engineering Record DATE 1974 X— FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D,C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X—EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The breakwaters at Lewes reflect three stages of construction: the two-part original breakwater, the connection between these two parts, and the outer break water. -

The Beauty of the Historic Brandywine Valley Proquest

1/10/2017 The beauty of the historic Brandywine Valley ProQuest 1Back to issue More like this + The beauty of the historic Brandywine Valley Kauffman, Jerry . The News Journal [Wilmington, Del] 04 Sep 2012. Full text Abstract/Details Abstract Translate The Victorian landscape movement was popular and in 1886 Olmstead recommended that the Wilmington water commissioners acquire the rolling creek-side terrain as a park to protect the city's water supply. Full Text Translate The landmark decision by the Mount Cuba Foundation and Conservation Fund to acquire the 1,100-acre Woodlawn Trustees property for a National Park was a watershed for the historic Brandywine Valley. Coursing through one of the most beautiful landscapes in America, no other river of its size can rival the Brandywine for its unique contributions to history and industry. The Brandywine rises in the 1,000-feet high Welsh Mountains of Pennsylvania and flows for 30 miles through the scenic Piedmont Plateau before tumbling down to Wilmington. The river provides drinking water to a quarter of a million people in two states, four counties, and 30 municipalities. Attracted to the pastoral countryside and nearby jobs in Wilmington and Philadelphia, 25,000 people have moved here since the turn of the century. Its watershed is bisected by an arc traced in 1682 by William Penn that is the only circular state boundary in the U.S. Though 90 percent of the catchment is in Pennsylvania, the river is the sole source of drinking water for Wilmington, Delaware's largest city. Delaware separated from Pennsylvania in 1776, but the two states remain joined by a common river.