Hyperhidrosis As the Presenting Symptom in Post-Traumatic Syringomyelia*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIMARY HYPERHIDROSIS Prevalence and Impacts for the Individual

PRIMARY HYPERHIDROSIS Prevalence and impacts for the individual Alexander Shayesteh Afshar Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine Dermatology and Venereology Umeå 2018 Copyright © Alexander Shayesteh Afshar 2018 This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) Dissertation for PhD ISBN: 978-91-7601-822-4 ISSN: 0346-6612 New Series No 1940 Cover art: “Drop Beads” by Grant Ware and Alexander Shayesteh Afshar Electronic version available at: http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: Umu Print Service Umeå, Sweden 2018 To Ladan, Gabriel and Isabell In medicine we ought to know the causes of sickness and health. And because health and sickness and their causes are sometimes manifest, and sometimes hidden and not to be comprehended except by the study of symptoms, we must also study the symptoms of health and disease. Avicenna 973-1037 CE Table of contents Abstract ............................................................................................ iii Abbreviations .................................................................................... v Sammanfattning på svenska ............................................................ vi List of papers .................................................................................. vii Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 Sweat ................................................................................................................................. 1 Sweat glands .................................................................................................................... -

Unilateral Hyperhidrosis Associated with Underlying Intrathoracic Neoplasia

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.41.10.814 on 1 October 1986. Downloaded from Thorax 1986;41:814-815 Unilateral hyperhidrosis associated with underlying intrathoracic neoplasia D C LINDSAY, J G FREEMAN, C 0 RECORD From the Department ofMedicine, Royal Victoria Infirmary, and University ofNewcastle upon Tyne Intrathoracic neoplasia is notable for the many ways in wall. There were metastatic plaques in the right hemithorax which it may present. We would like to report two cases and abdominal cavity but no evidence of metastases in the demonstrating a rare association between unilateral local- brain or the spinal cord. ised hyperhidrosis of the thoracic cage and underlying intra- thoracic neoplasm. Discussion Case reports The association of intrathoracic malignancy with sym- pathetic neurological complications, especially Homer's CASE 1 syndrome, is well recognised, particularly in the case of A 67 year old retired shotblaster complained ofa 3 kg weight tumours occurring at the thoracic inlet. Unilateral hyper- loss, mild dyspnoea, chest pain localised to the right costal hidrosis is an unusual phenomenon which has been reported margin, and profuse sweating localised to an area below the sporadically in association with various conditions, includ- right scapula. He smoked 15 cigarettes per day. Examination ing intracranial malignancy, encephalitis, syringomyelia, confirmed a right sided localised band of sweating at the trauma, neuritis, cervical rib, osteoma of the dorsal spine, level ofT6-9 posteriorly. Apart from minimal winging ofthe and chickenpox; in several cases no obvious underlying right scapula and some wasting of the right suprascapular cause has been evident. muscles no abnormal neurological signs were detected. -

Treatment of Hyperhidrosis Dr

“ Finding a solution to my sweating problem has With advanced technology and skilled hands, wholly changed my life. After having the Botox Matthew R. Kelleher, MD provides a full Premier Dermatology spectrum of services and procedures, including: for hyperhidrosis treatment, I am a thousand • Liposculpture times more confi dent and no longer afraid to • Botox, Juvéderm®, and Voluma™ Treatment TREATMENT OF lift my arms and be completely myself. I am so of Wrinkles thankful that this treatment exists!” • Laser Removal of Age Spots and Freckles HYPERHIDROSIS • Laser Facial Rejuvenation - Olivia • Laser Hair Removal Botox for hyperhidrosis patient • Laser Treatments of Rosacea, Facial Redness, and Spider Veins • Laser Scar Reduction • Laser Treatment of Stretch Marks “ Suffering from axillary hyperhidrosis, I thought • Laser Tattoo Removal • Laser Removal of Vascular Birthmarks there was nothing I could do. My condition • Laser and Photodynamic Treatment of Acne made me reluctant to participate in any social • Sclerotherapy for Leg Veins environment. Every day was a struggle until • Thermage® Radiofrequency Tissue Tightening liposuction for hyperhidrosis changed my life! • Microdermabrasion • Botox and Liposculpture Treatment of Hyperhidrosis Dr. Kelleher gave me the confi dence to feel • Sculpsure and Kybella for nonsurgical body sculpting comfortable in my own skin, and I never have to worry about embarrassing sweat stains again!” - Matthew Liposculpture for hyperhidrosis of the underarms patient “ After dealing with my excessive sweating for many years, without fully understanding it was a medical condition, Dr. Kelleher took the time to explain the treatment options available along with their results. I experienced immediate, positive results after my fi rst treatment which gave me a new sense of confi dence and removed the insurmountable stress I carried daily. -

Hyperhidrosis: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatment with Emphasis on the Role of Botulinum Toxins

Toxins 2013, 5, 821-840; doi:10.3390/toxins5040821 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Review Hyperhidrosis: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatment with Emphasis on the Role of Botulinum Toxins Amanda-Amrita D. Lakraj 1, Narges Moghimi 2 and Bahman Jabbari 1,* 1 Department of Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT 06520, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-203-737-2464; Fax: +1-203-737-1122. Received: 12 February 2013; in revised form: 27 March 2013 / Accepted: 12 April 2013 / Published: 23 April 2013 Abstract: Clinical features, anatomy and physiology of hyperhidrosis are presented with a review of the world literature on treatment. Level of drug efficacy is defined according to the guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology. Topical agents (glycopyrrolate and methylsulfate) are evidence level B (probably effective). Oral agents (oxybutynin and methantheline bromide) are also level B. In a total of 831 patients, 1 class I and 2 class II blinded studies showed level B efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA (A/Ona), while 1 class I and 1 class II study also demonstrated level B efficacy of AbobotulinumtoxinA (A/Abo) in axillary hyperhidrosis (AH), collectively depicting Level A evidence (established) for botulinumtoxinA (BoNT-A). In a comparator study, A/Ona and A/Inco toxins demonstrated comparable efficacy in AH. For IncobotulinumtoxinA (A/Inco) no placebo controlled studies exist; thus, efficacy is Level C (possibly effective) based solely on the aforementioned class II comparator study. -

Hyperhidrosis Hyperhidrosis Is a Condition Characterised by Abnormally Increased Sweating, in Excess of That Required for Regulation of Body Temperature

20 Dermatology Hyperhidrosis Hyperhidrosis is a condition characterised by abnormally increased sweating, in excess of that required for regulation of body temperature. Hyperhidrosis can either be generalised or localised to specifc parts of the body, such as hands, feet and axillae. Hyperhidrosis can be divided into primary or idiopathic, and a secondary type. Te primary type usually starts during adolescence or even earlier, while secondary hyperhidrosis can start at any point in life. Te latter form may be due to a disorder of the thyroid or pituitary gland, diabetes mellitus, tumours, gout, menopause, or certain medications. Tis article highlights the clinical features and the treatment options for this condition. Nabil Aly, Consultant Physician, University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool email [email protected] Epidemiology Hyperhidrosis is sweating in axillae; localised hyperhidrosis, excess of that required for and generalised hyperhidrosis.1,2 normal thermoregulation. It is a Localised hyperhidrosis, unlike People of all ages can be afected condition that usually begins in generalised hyperhidrosis, by hyperhidrosis. Primary either childhood or adolescence usually begins in childhood or hyperhidrosis affects men and can affect any site on the adolescence. Localised unilateral and women equally, and most body. However, the sites most or segmental hyperhidrosis is commonly occurs among people commonly afected are the palms, rare and of unknown origin. aged 25–64 years. Some may soles, and axillae. Excessive The condition usually presents have been affected since early sweating may be primary on the forearm or forehead in childhood, and about 30–50% (idiopathic) or secondary to otherwise healthy individuals, have another family member medication use, certain diseases, without evidence of the typical afflicted, implying a genetic metabolic disorders, or febrile triggering factors found in predisposition.5 Localised illnesses. -

Unilateral Hyperhidrosis Secondary to Brainstem Meningioma Producing Mass Effect

Volume 25 Number 11| November 2019| Dermatology Online Journal || Photo Vignette 25(11):9 Unilateral hyperhidrosis secondary to brainstem meningioma producing mass effect Ashlee Margheim1 BSN, Courtney R Schadt2 MD Affiliations: 1University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky, USA, 2Division of Dermatology, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, USA Corresponding Author: Ashlee Margheim, BSN, 3810 Springhurst Boulevard, Louisville, KY 40241, Tel: 502-572-4739, Email: [email protected] lesions of the hypothalamus, and cerebral or Abstract brainstem strokes [2, 3]. We report a case of a 61- Unilateral hyperhidrosis of neurological origin has year-old man with isolated sweating on the left been associated with head trauma, cerebral palsy, side of his entire body; a right-sided brainstem spinal cord injury, peripheral neuropathy, lesions meningioma producing mass effect is the of the hypothalamus, and cerebral or brainstem suspected underlying cause. strokes. In this report, we describe a 61-year-old man with isolated sweating on the left side of his entire body. A right-sided brainstem meningioma producing mass effect is suspected as the Case Synopsis underlying etiology. A 61-year-old right-handed male with no known medical history presented to the dermatologist Keywords: unilateral hyperhidrosis, meningioma with complaints of sweating on the left side of the body, including face, trunk, left arm, and left leg for a duration of one year. He reported sweating that drenched his clothes on occasion that was Introduction worse during the summer months. The patient Hyperhidrosis is defined as a condition of emphasized a clear line of demarcation between excessive sweating that exceeds the left and right sides of his body, with excessive thermoregulatory requirements. -

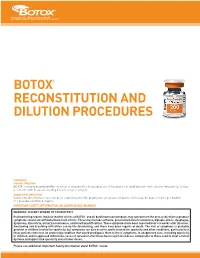

Botox® Reconstitution and Dilution Procedures

BOTOX® RECONSTITUTION AND DILUTION PROCEDURES Indication Chronic Migraine BOTOX® (onabotulinumtoxinA)for injection is indicated for the prophylaxis of headaches in adult patients with chronic migraine (≥ 15 days per month with headache lasting 4 hours a day or longer). Important Limitations Safety and effectiveness have not been established for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine (14 headache days or fewer per month) in 7 placebo-controlled studies. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION, INCLUDING BOXED WARNING WARNING: DISTANT SPREAD OF TOXIN EFFECT Postmarketing reports indicate that the effects of BOTOX® and all botulinum toxin products may spread from the area of injection to produce symptoms consistent with botulinum toxin effects. These may include asthenia, generalized muscle weakness, diplopia, ptosis, dysphagia, dysphonia, dysarthria, urinary incontinence, and breathing difficulties. These symptoms have been reported hours to weeks after injection. Swallowing and breathing difficulties can be life threatening, and there have been reports of death. The risk of symptoms is probably greatest in children treated for spasticity, but symptoms can also occur in adults treated for spasticity and other conditions, particularly in those patients who have an underlying condition that would predispose them to these symptoms. In unapproved uses, including spasticity in children, and in approved indications, cases of spread of effect have been reported at doses comparable to those used to treat cervical dystonia and upper limb spasticity and at lower -

Abstract Introduction

Volume 22 Number 10 October 2016 Letter Glycopyrrolate-induced craniofacial compensatory hyperhidrosis successfully treated with oxybutynin: report of a novel adverse effect and subsequent successful treatment Megan E Prouty1 BS, Ryan Fischer2 MD and Deede Liu2 MD Dermatology Online Journal 22 (10): 21 1 University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK 2 University of Kansas Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, Kansas City, KS Correspondence: Dr. Ryan Fischer 3901 Rainbow Blvd Division of Dermatology Kansas City, KS 66160 Tel. 859-699-8096 Email: [email protected] Abstract Hyperhidrosis, or abnormally increased sweating, is a condition that may have a primary or secondary cause. Usually medication- induced secondary hyperhidrosis manifests with generalized, rather than focal sweating. We report a 32-year-old woman with a history of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis for 15 years who presented for treatment and was prescribed oral glycopyrrolate. One month later, the palmoplantar hyperhidrosis had resolved, but she developed new persistent craniofacial sweating. After an unsuccessful trial of clonidine, oxybutynin resolved the craniofacial hyperhidrosis. To our knowledge, this is the first case of compensatory hyperhidrosis secondary to glycopyrrolate reported in the literature. The case highlights the importance of reviewing medication changes that correlate with new onset or changing hyperhidrosis. It also demonstrates a rare drug adverse effect with successful treatment. Keywords: Hyperhidrosis; Craniofacial; Glycopyrrolate; Compensatory Introduction Hyperhidrosis is characterized by excessive sweating beyond normal parameters of thermoregulatory need. Hyperhidrosis may be classified as primary or secondary. Primary hyperhidrosis occurs without an identifiable cause, whereas secondary hyperhidrosis is a result of an underlying medical condition or drug [1]. -

Sweating Bullets: Hyperhidrosis Fact Sheet

INTERNATIONAL HYPERHIDROSIS International Hyperhidrosis Society SOCIETY 2560 Township Road, Suite B Quakertown, PA 18951 USA SWEATING BULLETS: HYPERHIDROSIS FACT SHEET WHAT IS • Hyperhidrosis is a treatable medical condition that results in sweating that exceeds the normal amount HYPERHIDROSIS? required to maintain consistent body temperature. • It is estimated that up to eight million people or three percent of the U.S. population has this condition. • Patients with hyperhidrosis produce up to five times the average volume of sweat. • This excessive sweating occurs regardless of environmental surroundings – people with hyperhidrosis sweat profusely nearly all day, every day. CAUSES OF • People with hyperhidrosis are thought to produce too much of a specific neurotransmitter in the HYPERHIDROSIS sympathetic nervous system, or to have sweat glands that overreact to normal levels of the neurotrans- mitter. In either case, excessive, profuse sweating is the result. TYPES OF • Primary focal hyperhidrosis refers to excessive sweating that is not caused by another medical condi- HYPERHIDROSIS tion or as a result of a medication. ■ This type of sweating always occurs on very specific areas of the body and is usually symmetrical on the body. ■ The most common focal areas are the armpits (axillary hyperhidrosis), palms of hands (palmar hyperhidrosis), the face (facial hyperhidrosis) or the feet (plantar hyperhidrosis) ■ Primary focal hyperhidrosis of the hands and feet most often begins in childhood or adolescence. ■ People with primary hyperhidrosis usually do not experience excessive sweating while sleeping. ■ Research seems to indicate that primary focal hyperhidrosis can be inherited • Secondary generalized hyperhidrosis is excessive sweating that occurs as a symptom of other medical conditions such as anxiety disorders, diabetes, thyroid malfunction, nerve damage, and menopause or as a side effect of medication. -

BOTOX® Safely and Effectively

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION Blepharospasm: 1.25 Units-2.5 Units into each of 3 sites per affected eye These highlights do not include all the information needed to use (2.6) ® BOTOX safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Strabismus: 1.25 Units-2.5 Units initially in any one muscle (2.7) BOTOX. _____________________ _______________________ DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS BOTOX (onabotulinumtoxinA) Single-use, sterile 50 Units, 100 Units, or 200 Units vacuum-dried powder for Initial U.S. Approval: 1989 reconstitution only with sterile, non-preserved 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection USP prior to injection (3) WARNING: Distant Spread of Toxin Effect ______________________________ _________________________________ See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. CONTRAINDICATIONS The effects of BOTOX and all botulinum toxin products may Hypersensitivity to any botulinum toxin preparation or to any of the spread from the area of injection to produce symptoms consistent components in the formulation (4.1, 5.3, 6.2) with botulinum toxin effects. These symptoms have been reported Infection at the proposed injection site (4.2) hours to weeks after injection. Swallowing and breathing ________________________ ________________________ difficulties can be life threatening and there have been reports of WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS death. The risk of symptoms is probably greatest in children treated Potency Units of BOTOX not interchangeable with other preparations of for spasticity but symptoms can also occur in adults, particularly in botulinum toxin products (5.1, 11) those patients who have underlying conditions that would Spread of toxin effects; swallowing and breathing difficulties can lead to predispose them to these symptoms. -

HYPERHIDROSIS 101: Understanding Excessive Sweat

HYPERHIDROSIS 101: Understanding Excessive Sweat Hyperhidrosis is a medical condition in which excessive sweating occurs beyond what is needed to maintain normal body temperature.1,2 Excessive sweating can occur in the hands, feet, underarms or face, and it often interferes with everyday activities.1 Understanding Sweat Sweat glands are small tubular structures in the skin that secrete sweat onto the skin via a duct.3 Eccrine sweat glands are distributed throughout almost the entire human body and they secrete directly onto the surface of the skin.3 Apocrine sweat glands are ten times larger than eccrine sweat glands.3 They are localized in the axilla (underarms) and perianal areas.3 Rather than directly opening onto the skin surface, these glands secrete sweat into the pilary canal of the hair follicle.3 What is Hyperhidrosis? We all sweat. It’s the body’s way of cooling itself and preventing 1 ourselves from overheating. People living with hyperhidrosis, What Causes Us to Sweat? however, sweat when the body doesn’t necessarily need cooling.1 Their sweat is excessive, often visible to others and usually occurs The main reason we sweat is to control without physical exertion or extreme heat. our body temperature.2 There are two different types of hyperhidrosis - primary (also known as focal Here’s how it works: Sensors in our skin can detect changes in temperature hyperhidrosis) and secondary hyperhidrosis.6 Primary hyperhidrosis often begins and relay signals to our brain when we in childhood or adolescence and affects localized areas of the body, including the exercise or when it is hot outside.4 In hands, feet, underarms or face.6 The condition may be inherited and many members turn, our brain signals the sweat glands 7 of the same family may suffer from hyperhidrosis. -

Sweaty, Smelly Hands and Feet

THEME HANDS AND FEET Catherine E Scarff MBBS, MMed, FACD, is a dermatologist, Skin and Cancer Foundation, Carlton, Victoria. [email protected] Sweaty, smelly hands and feet Background Case study – Sally Palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with or without offensive Sally is a cleaner, 44 years of age, who lives alone. She has suffered from odour (bromhidrosis), can have a devastating effect on a sweaty palms and soles since her teens. She recalls being called out in patient’s life. The condition usually begins in childhood or front of the class in primary school to explain why her homework was adolescence and can impact greatly on education, career ‘smudged and ruined – again’. She left school early and started work as a cleaner. She has few friends, and a limited social network. She likes choices and social development. her work as she spends a lot of the day by herself. She has developed a Objective large number of techniques to avoid shaking hands with others and other This article describes the presentation, investigation and forms of physical contact. She has taken weeks to pluck up the courage management options for palmoplantar hyperhidrosis. to come and see you regarding her sweaty palms (Figure 1a, b) and soles. Her brother is getting married soon and as part of the bridal party, Discussion Sally knows she will have to hold hands and dance with her partner. She Clinical history and examination is often sufficient to make sits in front of you, shy and embarrassed. What do you do? a diagnosis of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis. Fortunately, Figure 1a, b.