Population Studies Research Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reportof the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for the Year Ended June

South BSS& Australia. REPORT CHIEF PROTECTOR OF ABORIGINALS FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30. 1925. R. E. E. Rogers Government Printer North Terrace. A 1925 Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007, RS 25.5/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library REPORT. Aboriginals Department, Adelaide, September 28th, 1925. Sir—I have the honor to submit this my report on the working of the Aboriginals Department for the year ended June 30th, 1925 ; also reports received from the Super intendents of the Aboriginal Stations and the Protectors of Aborigines in the North. POINT PEARCE STATION. The harvest results for the past season were disappointing in yield, wheat only averaging 9bush. per acre. However, as good prices for wheat, barley, and wool were obtained, the year's operations show a profit of £198 18s. 2d. The total rainfall for year ended December 31st, 1924, was 11.67in. Mr. W. R. Penhall resigned his position as Superintendent on October 31st, 1924, and Mr. J. B. Steer was transferred from Point McLeay to this position. Mr. Steer takes a keen interest in stock and agriculture and is well qualified for the position. POINT MCLEAY STATION. Owing to the increasing cost of firewood for this station, and the loss in return from the dairy, caused by the culling out of cows not up to standard, on the advice of the herd tester, also the drier season, this station shows a loss of £5,123 15s. l1d. The loss on the dairy will be only tem porary, as this system of herd testing will eventually make the dairy much more profitable, and we hope this year to reduce the cost of firewood, as we have arranged to cut and cart same with our own men and teams, instead of letting this contract to white men, which has been done previously. -

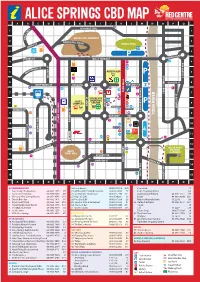

Alice Springs Cbd Map a B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 14 Schwarz Cres 1 Es 1 R C E

ALICE SPRINGS CBD MAP A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 14 SCHWARZ CRES 1 ES 1 R C E L E ANZAC HILL LOOKOUT H 2 ZAC H 2 AN ILL ROAD ST ANZAC OVAL TH SMI 3 P 3 UNDOOLYA RD STOKES ST WILLS TERRACE 4 8 22 4 12 LD ST 28 ONA 5 CD ALICE PLAZA 5 M P 32 LINSDAY AVE LINSDAY COLSON ST COLSON 4 6 GOYDER ST 6 WHITTAKER ST PARSONS ST PARSONS ST 43 25 20 21 9 1 29 TODD TODD MALL 7 38 STURT TERRACE 7 11 2 YEPERENYE 16 COLES SHOPPING 36 8 CENTRE 48 P 8 COMPLEX 15 BATH ST BATH 33 HARTLEY ST REG HARRIS LN 45 27 MUELLER ST KIDMAN ST 23 FAN ARCADE LEICHARDT TERRACE LEICHARDT 9 37 35 10 9 GREGORY TCE RIVER TODD 7 RAILWAY TCE RAILWAY 10 HIGHWAY STUART 10 24 41 46 P 47 GEORGE CRES GEORGE 44 WAY ONE 11 32 11 26 40 TOWN COUNCIL FOGARTY ST LAWNS 3 5 34 12 STOTT TCE 12 42 OLIVE PARK LARAPINTA DRV BOTANIC BILLY 39 31 GARDENS 13 GOAT HILL 13 6 13 STUART TCE 18 TUNCKS RD SIMPSON ST STREET TODD 14 19 14 17 49 15 SOUTH TCE 15 BARRETT DRV A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q ACCOMMODATION 24. Loco Burrito 08 8953 0518 K10 Centrelink F5 1. Alice Lodge Backpackers 08 8953 1975 P7 25. McDonald’s Family Restaurant 08 8952 4555 E7 Coles Shopping Centre G8 2. -

Alice Springs Region Economic Profile at a Glance

Alice Springs Region Economic Profile At a glance www.regionaldevelopment.nt.gov.au Alice Springs Region at a glance This economic snapshot of Central Australia provides some facts The Central Australia region contributes an estimated about the region and highlights key aspects of the local economy 18 per cent ($2.9 billion) of the Northern Territory Gross State and how it is changing over time. Product. Of this, the largest industry sectors are Mining Seventeen percent (41 042) of Territorians live in the Central ($552 million), Construction ($313 million) and Health care and Australia region, an area of almost 570,000 square kilometres. social assistance ($240 million). The region includes Alice Springs, the second largest population At $54 450, the average income in the Central Australia region centre in the Northern Territory and the economic, business and is lower than the NT average ($59 342). This can largely be service hub for the region. Residents from remote areas of attributed to the labour intensive service sectors associated with South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland also access the accommodation, retail, construction, public administration many services from Alice Springs such as health and retail. and health care sectors. The average cost of a basket of goods in Alice Springs is comparable with Darwin, but cheaper than Katherine and Nhulunbuy. Source: Department of Local Government www.regionaldevelopment.nt.gov.au Society What are the labour force characteristics in the region? DEMOGRAPHY Total population at Census 2006 2011 Alice Springs Region minus Alice Springs Town (T) = Alice Springs balance (bal.) Alice Springs (T) 26,467 28,080 Alice Springs bal. -

Tennant Creek Telegraph Station Self Guided Walk Information Sheet

Tennant Creek Telegraph Station Self Guided Walk Welcome to the Tennant Meanwhile, you and your team the closing of these buildings as Creek Telegraph Station are responsible for manning the a post and telegraph office. These telegraph equipment 24 hours functions were transferred to the This guide provides additional a day. You need to check and nearby town along with all of the information to the signs located maintain the line itself north original equipment. However, around the site. There is a map and south of the station. Your the buildings continued to be of the site on the last page of this blacksmith is responsible for used as accommodation for line leaflet that can help you find your repairing and making any tools maintenance staff until the 1950s. way around as you take the self- and equipment that you need. guided tour. To explore inside the You are also responsible for Pastoral Era buildings, keys are available for a garden and small allocation The telegraph station has always hire from the tourist information of sheep and cattle to provide had a pastoral history. When first desk at the Battery Hill Mining fresh food. You supply rations established it had a 20 square Centre in Tennant Creek. to local Aboriginal people and mile grazing lease, in addition to provide medical service in the the building site, and was stocked absence of practitioners. Before you start, imagine... mainly with sheep for meat with some cattle for dairy products. As you enter the site take time More than a Telegraph to look around you. -

3 Days the Ghan

ITINERARY THE GHAN South Australia – Adelaide Adelaide – Alice Springs – Darwin Travel from Australia’s south to north on one of the world’s greatest train journeys. Board in Adelaide and watch South Australia’s rolling green hills make way for desert, the rusty Red Centre and finally the tropical splendour of the Top End. AT A GLANCE DAY ONE ADELAIDE – ALICE SPRINGS Look out at the small, rustic railway Board Adelaide midday towns and vast tracts of Aboriginal land, where communities have maintained Settle into your cabin or seat and their connection with the land for watch Adelaide’s gracious edges thousands of years. In the morning, flatten into wine country, desert and you’ll cross the Northern Territory border scrubs. Pass through coastal Coonamia and travel through the small bush > Adelaide – Alice Springs (25 hours) and Port Augusta. Cross over Dog town of Kulgera and over the sandy Fence, the world’s longest fence and Finke River. Take in the multicoloured > Alice Springs – Katherine (15 hours) speed through Cadney Homestead vistas with morning tea before arriving > Katherine – Darwin (4.5 hours) at the gateway to the Painted Desert. in Alice Springs. > 2 nights on board The Ghan ITINERARY DAY TWO AND THREE USEFUL LINKS ALICE SPRINGS – KATHERINE Gorge past magnificent sandstone cliffs The Ghan http://www.greatsouthernrail.com.au/ Arrive Alice Springs midday or fly over its interconnecting gorges on a helicopter. Get up close to the birds trains/the_ghan Explore Alice Springs on one of the many and animals of Nitmiluk National Park Adelaide whistle stop tours. Learn about the area’s on a nature cruise or canoe down the outback pioneers or immerse yourself in its http://www.australia.com/en/places/ Katherine River. -

Splendors of Australia & New Zealand

AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND Guaranteed small group of no more than 24 Smithsonian travelers per departure SPLENDORS OF AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND 22 days from $9,178 total price from Los Angeles ($8,195 air & land inclusive plus $983 airline taxes and departure fees) mall group touring provides the best way S to explore the Lands Down Under. Join us on a grand adventure from Australia’s spectacular Great Barrier Reef to the storied Outback and sophisticated Sydney. In New Zealand discover vineyards, sheep farms, towering Mt. Cook, breathtaking Milford Sound, as well as high- spirited Queenstown and nautical Auckland. Destination Cairns Air Motorcoach Alice Springs Coral Sea Entry/Departure Ayers Rock AUSTRALIA Auckland Sydney Rotorua Mount Cook Christchurch National Park Tasman Sea NEW Queenstown ZEALAND Serene Milford Sound ranks as New Zealand’s most popular destination. Avg. High (°F) Jan Feb Mar Apr Oct Nov Sydney 78 78 76 71 71 74 Days 1-2: Depart the U.S. for Cairns, Australia around a campfire, enjoy musical entertainment, Alice Springs 97 95 90 81 88 93 Fly to Australia, losing a day as you cross the Inter- and look for the Southern Cross and other constella- Queenstown 72 72 68 62 60 64 national Date Line. tions at a traditional “bush” dinner. Spend the next day exploring more rugged terrain as you visit the Days 3-5: Australia’s Far North—Cairns, Kuranda, camp of the Walpiri Aboriginal people and learn the Great Barrier Reef Arrive in Cairns and about their ancient culture on a “Dreamtime” tour. Your Small Group Tour Highlights enjoy a special welcome dinner. -

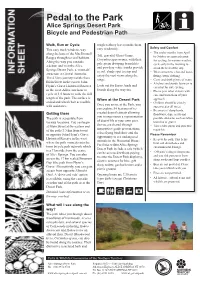

Bicycle and Pedestrian Path Map

Pedal to the Park Alice Springs Desert Park Bicycle and Pedestrian Path Walk, Run or Cycle tough leathery leaves make them Safety and Comfort This easy track winds its way easy to identify. • The cooler months from April along the base of the MacDonnell Tall, graceful Ghost Gums, Ranges through several habitats. to October are more pleasant Corymbia aparrerinja, with their for cycling. In warmer weather, Along the way you can take pale green drooping branchlets a detour and visit the Alice cycle early in the morning to and powdery white trunks provide avoid the heat of the day. Springs Desert Park, a ‘must-do’ a cool, shady spot to stop and • Wear sunscreen, a hat and loose- attraction in Central Australia. enjoy the vast views along the fitting cotton clothing. The 4.5 km journey travels from range. • Carry and drink plenty of water. Blain Street in the east to John • A helmet and sturdy footwear is Look out for Euros, birds and Flynn’s Grave Historical Reserve essential for safe cycling. in the west. Allow one hour to lizards along the way too. • Please pass other visitors with cycle or 1.5 hours to walk the full care and warn them of your length of the path. The surface is approach. When at the Desert Park sealed and wheelchair accessible • Children should be closely Once you arrive at the Park, you with assistance. supervised at all times. can explore 54 hectares of re- • Be aware of sharp bends, created desert habitats allowing Getting there floodways, dips, crests and you to experience a representation The path is accessible from possible obstacles such as fallen of desert life at your own pace. -

Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration DECEMBER 2019 Mparntwe (Pronounced M-Ban Tua) Is the Arrernte Name for Alice Springs

Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration DECEMBER 2019 Mparntwe (pronounced M-ban tua) is the Arrernte name for Alice Springs. The Aboriginal Arrernte (pronounced arrunda) peoples are the traditional custodians of Alice Springs and the surrounding region. This Declaration is made by all Australian Education Ministers: Ms Yvette Berry MLA Minister for Education and Early Childhood Development (Australian Capital Territory) The Hon Dan Tehan MP Minister for Education (Australian Government) Chair, Ministerial Council on Education The Hon Sarah Mitchell MLC Minister for Education and Early Childhood Learning (New South Wales) The Hon Selena Uibo MLA Minister for Education (Northern Territory) The Hon Grace Grace MP Minister for Education (Queensland) The Hon John Gardner MP Minister for Education (South Australia) The Hon Jeremy Rockliff MP Minister for Education and Training (Tasmania) The Hon James Merlino MP Minister for Education (Victoria) The Hon Suzanne Ellery MLC Minister for Education and Training (Western Australia) Contents Story Preamble 2 Ceremony, Karrinyarra by Nerine Tilmouth represents Water Dreaming (also called Kapi, The Education Goals for Young Australians 4 or Ngapa Tjukurrpa), from Karrinyarra and Central Mt Wedge, north of Goal 1: The Australian education system promotes Papunya in Central Australia. The circles excellence and equity 5 represent water holes, and this site is Goal 2: All young Australians become confident and strongly associated with rain making creative individuals, successful lifelong learners, ceremonies. Karrinyarra represents an and active and informed members of the community 6 important cultural point of intersection, where people come together to share in access to the resources, and to take A Commitment to Action 9 responsibility for the Country and its Law. -

Katherine Region Economic Profile at a Glance

Katherine Region Economic Profile At a glance www.regionaldevelopment.nt.gov.au Katherine Region at a glance This economic snapshot provides some facts about the Katherine The top three employing sectors in the region are public Region and highlights key aspects of the local economy and how administration and safety (1 922), health and social assistance it has changed over time. (910) and education and training (752). However, most Approximately 4.5 percent (10 641) of Territorians live in employment growth between 2006 and 2011 Census occurred in the Katherine Region, an area of 326 327 square kilometres. other services (112 percent), mining (62 percent) and electricity, Katherine is a major transport hub strategically located on a road gas, water, and waste services (59 percent). junction connecting the Ord River and the Kimberley Region of Between 2011 and 2012, the average cost of a basket of goods Western Australia, Alice Springs and Adelaide to the south, and in the Katherine Region declined approximately 4 percent. Queensland to the east. Katherine is connected by rail to the ABS geography changes are reflected in this document, therefore north and south and plays a pivotal role in connecting the trade care should be taken when making comparisons with previous route in regions located east, west and south to the major port version of this document. of Darwin in the north. Due to ABS geography changes, Katherine Region is as per ABS Statistical The Katherine Region produces an estimated 7.4 percent ($1 338 Area 3(SA3). Katherine Town is as per ABS Statistical Area 2(SA2). -

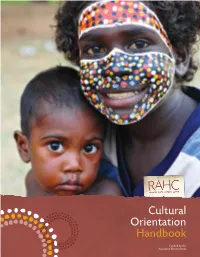

RAHC Cultural Orientation Handbook Is the First Part of the Training and Orientation Program You Will Undertake

Cultural Orientation Handbook Funded by the Australian Government Photographs used in this handbook were taken in the Northern Territory communities of Ampilatwatja, Ti Tree, Imanpa and Galiwin’ku. Permission was sought from these communities and from all individuals or guardians of individuals, before photography commenced. All photographs are copyright of the Remote Area Health Corps. © Copyright - Remote Area Health Corps, RAHC, 2013 Contents Welcome ..........................................4 Working within the Dying, death and kinship network ...........................27 sorry business .............................. 35 Introduction to this handbook ........................................5 The kinship network Dying Roles and responsibilities Death Your first days .................................7 Avoidance and Poison relationships Sorry business Permits Where do you fit in? Other cultural considerations Forbidden areas and sacred sites When offered a skin name relating to treatment ................ 39 Alcohol Working with the right members Blame and payback Introductions of the kinship network Curses Adjusting to your role Reciprocity — sharing Traditional healers Working with Elders Working within the Use of ochre Aboriginal community ..............11 Birth and childhood .................. 33 Treatment arising from The Aboriginal community Birth ceremonial activity Factionalism and politics Childhood Hair and clothing Engaging with the community Men’s and Women’s business Personal presentation Treatment compliance ............ -

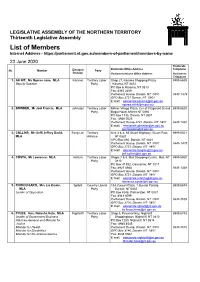

List of Members Internet Address

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Thirteenth Legislative Assembly List of Members Internet Address - https://parliament.nt.gov.au/members-of-parliament/members-by-name 23 June 2020 Electorate Electoral Electorate Office Address Telephone No. Member Party Division Parliament House Office Address Parliament Telephone 1. AH KIT, Ms Ngaree Jane, MLA Karama Territory Labor Shop 27, Karama Shopping Plaza, 8999 6659 Deputy Speaker Party Karama, NT 0812 PO Box 6, Karama, NT 0813 Fax: 8945 2090 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1479 GPO Box 3721 Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 2. BOWDEN, Mr Joel Francis, MLA Johnston Territory Labor Millner Village Plaza, Cnr of Fitzgerald St and 8999 6620 Party Bagot Road, Millner NT 0810 PO Box 1135, Darwin, NT 0801 Fax: 8948 0525 Parliament House 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 8946 1490 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 3. COLLINS, Mr (Jeff) Jeffrey David, Fong Lim Territory Unit 3 & 4, 65 Stuart Highway, Stuart Park, 8999 6501 MLA Alliance NT 0820 GPO Box 892, Darwin, NT 0801 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1475 GPO Box 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 4. COSTA, Mr Lawrence, MLA Arafura Territory Labor Shops 7 & 8, Moil Shopping Centre, Moil, NT 8999 6950 Party 0810 PO Box 41392, Casuarina, NT 0811 Fax: 8927 0988 8946 1438 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 GPO Box 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 5. -

Adelaide to Darwin Cheat Sheet

ADELAIDE TO DARWIN CHEAT SHEET THE GHAN ADELAIDE – ALICE SPRINGS – DARWIN DARWIN OPERATES ALL YEAR KATHERINE Sun 12.15 Depart Adelaide Marla | Morning Experience Mon 13.45 Arrive Alice Springs | Afternoon Excursion ALICE SPRINGS 18.15 Depart Alice Springs MARLA Katherine | Morning Excursion Tues 17.30 Arrive Darwin OPERATES JUNE 2019 TO AUGUST 2019 ADELAIDE Wed 12.10 Depart Adelaide Marla | Morning Experience Thurs 14.25 Arrive Alice Springs | Afternoon Excursion THE GHAN – ADELAIDE TO DARWIN TO – ADELAIDE THE GHAN 18.15 Depart Alice Springs Katherine | Morning Excursion Fri 19.50 Arrive Darwin * The Ghan does not operate December 2019 - January 2020 OFF TRAIN EXCURSIONS Enjoy extended touring options at key destinations along the rail route. OUTBACK EXPERIENCES Step off the train to immerse yourself in some of Australia’s most remote Outback settings. KEY SELLING POINTS OF JOURNEY o Overnight in the most popular choice of accommodation, Gold Service or KATHERINE: for the discerning traveller our highest level of service, Platinum Service o Nitmiluk Gorge Cruise o All inclusive fine dining with a regionally-inspired menu paired with a o Nitmiluk First Gorge Rock Art Cruise selection of local wines o Katherine Outback Experience o Off train excursions in each destination shown below: o UPGRADE $200 per person - Nitmiluk Gorge Helicopter Flight MARLA: o UPGRADE $400 per person – Twin Parks Fixed Wing Scenic Flight o Morning sunrise with freshly brewed coffee or juice ALICE SPRINGS: o Desert Park o Alice Explorer o Simpsons Gap Discovery Walk (long pants required in High Season) o UPGRADE $60 per person – Pyndan Camel Tracks o UPGRADE $200 per person – Spirit of Mt Gillen Helicopter Flight o UPGRADE $380 per person – Alice Springs & Surrounds Fixed Wing Scenic Flight ALL OFF TRAIN EXCURSIONS ARE INCLUDED IN YOUR CLIENTS JOURNEY UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED AND ARE BOOKED ONBOARD.