The History of Meteoritics - Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

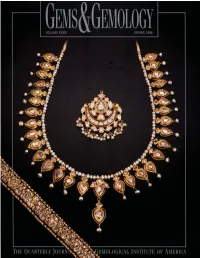

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

Cross-References ASTEROID IMPACT Definition and Introduction History of Impact Cratering Studies

18 ASTEROID IMPACT Tedesco, E. F., Noah, P. V., Noah, M., and Price, S. D., 2002. The identification and confirmation of impact structures on supplemental IRAS minor planet survey. The Astronomical Earth were developed: (a) crater morphology, (b) geo- 123 – Journal, , 1056 1085. physical anomalies, (c) evidence for shock metamor- Tholen, D. J., and Barucci, M. A., 1989. Asteroid taxonomy. In Binzel, R. P., Gehrels, T., and Matthews, M. S. (eds.), phism, and (d) the presence of meteorites or geochemical Asteroids II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 298–315. evidence for traces of the meteoritic projectile – of which Yeomans, D., and Baalke, R., 2009. Near Earth Object Program. only (c) and (d) can provide confirming evidence. Remote Available from World Wide Web: http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/ sensing, including morphological observations, as well programs. as geophysical studies, cannot provide confirming evi- dence – which requires the study of actual rock samples. Cross-references Impacts influenced the geological and biological evolu- tion of our own planet; the best known example is the link Albedo between the 200-km-diameter Chicxulub impact structure Asteroid Impact Asteroid Impact Mitigation in Mexico and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Under- Asteroid Impact Prediction standing impact structures, their formation processes, Torino Scale and their consequences should be of interest not only to Earth and planetary scientists, but also to society in general. ASTEROID IMPACT History of impact cratering studies In the geological sciences, it has only recently been recog- Christian Koeberl nized how important the process of impact cratering is on Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria a planetary scale. -

Jahrbuch Der Kais. Kn. Geologischen Reichs-Anstalt

Digitised by the Harvard University, Download from The BHL http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.biologiezentrum.at Die Meteoritensammlung des k. k. mineralogischen Hof kabinetes in Wien am I. Mai 1885. Von Dr. Aristides Breziua. Mit vier Tafe'.n (Nr. 11— V). Von dieser Saminluug, welche schon zu Chladm's Zeiten von hohem wissenschaftlichen Werthe war und seither inamer eine erste Stelle einnahm, ist seit dem Jahre 1872 keine vollständige Gewichts- liste veröffentlicht worden ; in dem genannten Jahre gab der damalige Director des Kabinetes, Hofrath G. Tschermak, ein Verzeichnisse), das er bei seinem Abgange vom Museum durch einen Nachtrag ^) bis Ende September 1877 vervollständigte. Als mir nach dem Ausscheiden Tschermak's von meinem seither verstorbenen Vorstande, Hofrath Ritter v. Hochstetter, die Obsorge über die Sammlung übertragen wurde, war es mein nächstes Ziel, die Fälle aus den letzten Jahr- zehnten zu vervollständigen und die vielen nur durch kleine Splitter von einem Gramm und darunter vertretenen Localitäten durch grössere Stücke zu repräsentiren, weil so kleine Fragmente die petrographische Beschaffenheit eines gemengten Körpers nicht genügend erkennen lassen. Es zeigte sich bald, dass ein solches Ziel nur durch Anlegung einer eigenen Meteoritentauschsammlung zu erreichen war, welche bei Gele- genheit grösserer Fälle oder Funde mit Doublettenmateriale zu billigen Preisen versehen werden konnte und dann die Erwerbung auch der selteneren und kostbareren Fallorte auf dem Tauschwege gestattete; denn die Meteoritenpreise sind gegen frühere Jahrzehnte so wesentlich gestiegen, dass eine Ergänzung der Sammlung durch vorwiegenden Ankauf nicht mehr möglich ist, während andererseits eine Abgabe an- sehnlicher Stücke aus der Hauptsammlung, wie sie unter Hoernes- Haidinger üblich war, eine gewisse Beweglichkeit der Sammlung hervorbringt, welche bei einem so kostbaren Materiale wohl vermieden werden soll ; auch ein Tausch mit kleinen, von den Hauptstücken abge- kueipten Splittern, wie er ebenfalls häufig stattfand, bringt nur einen ') Die Meteoriten des k, k. -

Planetary Surfaces

Chapter 4 PLANETARY SURFACES 4.1 The Absence of Bedrock A striking and obvious observation is that at full Moon, the lunar surface is bright from limb to limb, with only limited darkening toward the edges. Since this effect is not consistent with the intensity of light reflected from a smooth sphere, pre-Apollo observers concluded that the upper surface was porous on a centimeter scale and had the properties of dust. The thickness of the dust layer was a critical question for landing on the surface. The general view was that a layer a few meters thick of rubble and dust from the meteorite bombardment covered the surface. Alternative views called for kilometer thicknesses of fine dust, filling the maria. The unmanned missions, notably Surveyor, resolved questions about the nature and bearing strength of the surface. However, a somewhat surprising feature of the lunar surface was the completeness of the mantle or blanket of debris. Bedrock exposures are extremely rare, the occurrence in the wall of Hadley Rille (Fig. 6.6) being the only one which was observed closely during the Apollo missions. Fragments of rock excavated during meteorite impact are, of course, common, and provided both samples and evidence of co,mpetent rock layers at shallow levels in the mare basins. Freshly exposed surface material (e.g., bright rays from craters such as Tycho) darken with time due mainly to the production of glass during micro- meteorite impacts. Since some magnetic anomalies correlate with unusually bright regions, the solar wind bombardment (which is strongly deflected by the magnetic anomalies) may also be responsible for darkening the surface [I]. -

![(Sptpang Coil.) [I49] I50 Bulletin American Museum of Natural History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0767/sptpang-coil-i49-i50-bulletin-american-museum-of-natural-history-200767.webp)

(Sptpang Coil.) [I49] I50 Bulletin American Museum of Natural History

Article VIII.-CATALOGUE OF METEORITES IN THE COLLECTION OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, TO JULY i, I896. By E. 0. HOVEY. 'T'he Collection of Meteorites in the Arnerican Museum of Natural History consists of fifty-five slabs, fragments and com- plete individuals, representing twenty-six falls and finds. The foundation of the mineralogical department of the Museum was laid in I874 by the purchase of the collection of S. C. H. Bailey, in which there were a few meteorites. More were acquired with the portion of the Norman Spang Collection of Minerals which was purchased in I89I, and other meteorites have been bought by the Museum from time to time, or have been presented to it by friends. The soujrce from which each specimen came has been indicated in the following cataloguLe. This publication is made to assist. the large number of persons who have become interested in knowing the extent to which the material of various falls and finds has been distributed among collections and the present location of specimens. AEROSIDERITES. (IRON METEORI ES.) Cat. Date of NAME AND Weight No. Discovery. DE;SCRIPTION. in grams. 18 1784 Tejupilco, Toluca Valley, Mexico. A complete individual, the surface of which has scaled off somewhat. A polished and etched surface shows coarse Widmanstatten figures. 1153. (Bailey Co/i.) 17841 Xiquipilco, Toluca Valley, Mexico. A complete individual of ellipsoidal form, which had been used as a pounder by the natives. 564. (Sptpang Coil.) [I49] I50 Bulletin American Museum of Natural History. [Vol. VIII, AEROSIDERITES.-Continued. Cat. Date of NAME AND DESCRIPTION. -

Asteroids 2867 Steins and 21 Lutetia: Surface Composition from Far Infrared Observations with the Spitzer Space Telescope

A&A 477, 665–670 (2008) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20078085 & c ESO 2007 Astrophysics Asteroids 2867 Steins and 21 Lutetia: surface composition from far infrared observations with the Spitzer space telescope M. A. Barucci1, S. Fornasier1,2,E.Dotto3,P.L.Lamy4, L. Jorda4, O. Groussin4,J.R.Brucato5, J. Carvano6, A. Alvarez-Candal1, D. Cruikshank7, and M. Fulchignoni1,2 1 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, 92195 Meudon Principal Cedex, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Université Paris Diderot, Paris VII, France 3 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, via Frascati 33, 00040 Monteporzio Catone, Roma, Italy 4 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, BP 8, 13376 Marseille Cedex 12, France 5 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, via Moiariello 16, 80131 Napoli, Italy 6 Observatorio National (COAA), rua Gal. José Cristino 77, CEP20921–400 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 7 NASA Ames Research Center, MS 245-6, Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000, USA Received 14 June 2007 / Accepted 3 October 2007 ABSTRACT Aims. The aim of this paper is to investigate the surface composition of the two asteroids 21 Lutetia and 2867 Steins, targets of the Rosetta space mission. Methods. We observed the two asteroids through their full rotational periods with the Infrared Spectrograph of the Spitzer Space Telescope to investigate the surface properties. The analysis of their thermal emission spectra was carried out to detect emissivity features that diagnose the surface composition. Results. For both asteroids, the Christiansen peak, the Reststrahlen, and the Transparency features were detected. The thermal emissiv- ity shows a clear analogy to carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, in particular to the CO–CV types for 21 Lutetia, while for 2867 Steins, already suggested as belonging to the E-type asteroids, the similarity to the enstatite achondrite meteorite is confirmed. -

Metal-Silicate Fractionation and Chondrule Formation

A756 Goldschmidt 2004, Copenhagen 6.3.12 6.3.13 Metal-silicate fractionation and Fe isotopes fractionation in chondrule formation: Fe isotope experimental chondrules 1 2 2,3 constraints S. LEVASSEUR , B. A. COHEN , B. ZANDA , 2 1 1 1 1 2 2 R.H. HEWINS AND A.N. HALLIDAY X.K. ZHU , Y. GUO , S.H. TANG , A. GALY , R.D. ASH 2 AND R.K O’NIONS 1 ETHZ, Dep. of Earth Sciences, Zürich, Switzerland ([email protected]) 1 Lab of Isotope Geology, MLR, Chinese Academy of 2 Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, USA Geological Sciences, 26Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing, 3 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France China ([email protected]) 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Oxford University, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PR, UK Natural chondrules show an Fe-isotopic mass fractionation range of a few δ-units [1,2] that is interpreted either as the result of Fe depletion from metal-silicate Recent studies have shown that considerable variations of fractionation during chondrule formation [1] or as the Fe isotopes exist in both meteoritic and terrestrial materials, reflection of the fractionation range of chondrule precursors and that they are related, through mass-dependent [2]. In order to better understand the iron isotopic fractionation, to a single isotopically homogeneous source[1]. compositions of chondrules we conducted experiments to This implies that the Fe isotope variations recorded in the study the effects of reduction and evaporation of iron on iron solar system materials must have resulted from mass isotope systematics. fractionation incurred by the processes within the solar system About 80mg of powdered slag fayalite was placed in a itself. -

Australian Aborigines and Meteorites

Records of the Western Australian Museum 18: 93-101 (1996). Australian Aborigines and meteorites A.W.R. Bevan! and P. Bindon2 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 2 Department of Anthropology, Western Australian Museum, Francis Street, Perth, Western Australia 6000 Abstract - Numerous mythological references to meteoritic events by Aboriginal people in Australia contrast with the scant physical evidence of their interaction with meteoritic materials. Possible reasons for this are the unsuitability of some meteorites for tool making and the apparent inability of early Aborigines to work metallic materials. However, there is a strong possibility that Aborigines witnessed one or more of the several recent « 5000 yrs BP) meteorite impact events in Australia. Evidence for Aboriginal use of meteorites and the recognition of meteoritic events is critically evaluated. INTRODUCTION Australia, although for climatic and physiographic The ceremonial and practical significance of reasons they are rarely found in tropical Australia. Australian tektites (australites) in Aboriginal life is The history of the recovery of meteorites in extensively documented (Baker 1957 and Australia has been reviewed by Bevan (1992). references therein; Edwards 1966). However, Within the continent there are two significant areas despite abundant evidence throughout the world for the recovery of meteorites: the Nullarbor that many other ancient civilizations recognised, Region, and the area around the Menindee Lakes utilized and even revered meteorites (particularly of western New South Wales. These accumulations meteoritic iron) (e.g., see Buchwald 1975 and have resulted from prolonged aridity that has references therein), there is very little physical or allowed the preservation of meteorites for documentary evidence of Aboriginal acknowledge thousands of years after their fall, and the large ment or use of meteoritic materials. -

Re-Os ISOTOPIC CONSTRAINTS on the CRYSTALLIZATION HISTORY of IIAB IRON METEORITES

Lunar and Planetary Science XXVIII 1258.PDF Re-Os ISOTOPIC CONSTRAINTS on the CRYSTALLIZATION HISTORY of IIAB IRON METEORITES. M.I. Smoliar, R.J. Walker, J.W. Morgan. Dept. of Geol., Univ. MD, College Park, MD 20742 The IIAB group represents one of the clearest cases of face bet-ween IIA and IIB subgroups [4]. It also shows an fractional crystallization of metallic magma during core intermediate struc-ture - roughly half of this 2700 kg iron is formation. The Ni-Ir trend in the IIAB group (Fig. 1) has a a single hexahedral crystal of kamasite (typical for IIA sub- very steep negative slope which indicates a correspon- group), while the other part has the coarsest octahedral dingly high Ir distribution coefficient, and, consequently, structure, very similar to Navajo and Mount Joy - the neigh- high sulfur content in the parental metallic magma [1]. Sta- bors of Old Woman from IIB subgroup [5]. Specimens from tistical analyses of the IIAB Ni-Ir trend indicates that the both octahedral and hexahedral parts of Old Woman were observed scatter of datapoints along the ideal crystalli- analyzed. zation line is mostly due to analytical uncertainty. This Fig. 2 shows the Re-Os experimental results for the IIB implies that the Ni-Ir distribution pattern in IIAB irons re- meteorites along with previously publisued IIA isochron flects fractional crystallization, with no significant parallel ([7], age = 4.537 ± 8 Ga, initial 187Os/188Os ratio = 0.09550 or subsequent processes. Originally two separate groups ± 7, MSWD = 1.15). Low age uncertainty and low MSWD were recognized (IIA and IIB) on the basis of their different value imply that the whole IIA subgroup crystallized in a crystallographic structure and the prominent hiatus in the Ir narrow time interval not exceeding 16 m.y. -

Olivine-Dominated Asteroids and Meteorites: Distinguishing Nebular and Igneous Histories

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 42, Nr 2, 155–170 (2007) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Olivine-dominated asteroids and meteorites: Distinguishing nebular and igneous histories Jessica M. SUNSHINE1*, Schelte J. BUS2, Catherine M. CORRIGAN3, Timothy J. MCCOY4, and Thomas H. BURBINE5 1Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA 2University of Hawai‘i, Institute for Astronomy, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720, USA 3Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, Maryland 20723–6099, USA 4Department of Mineral Sciences, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560–0119, USA 5Department of Astronomy, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts 01075, USA *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 14 February 2006; revision accepted 19 November 2006) Abstract–Melting models indicate that the composition and abundance of olivine systematically co-vary and are therefore excellent petrologic indicators. However, heliocentric distance, and thus surface temperature, has a significant effect on the spectra of olivine-rich asteroids. We show that composition and temperature complexly interact spectrally, and must be simultaneously taken into account in order to infer olivine composition accurately. We find that most (7/9) of the olivine- dominated asteroids are magnesian and thus likely sampled mantles differentiated from ordinary chondrite sources (e.g., pallasites). However, two other olivine-rich asteroids (289 Nenetta and 246 Asporina) are found to be more ferroan. Melting models show that partial melting cannot produce olivine-rich residues that are more ferroan than the chondrite precursor from which they formed. Thus, even moderately ferroan olivine must have non-ordinary chondrite origins, and therefore likely originate from oxidized R chondrites or melts thereof, which reflect variations in nebular composition within the asteroid belt. -

Lost Lake by Robert Verish

Meteorite-Times Magazine Contents by Editor Like Sign Up to see what your friends like. Featured Monthly Articles Accretion Desk by Martin Horejsi Jim’s Fragments by Jim Tobin Meteorite Market Trends by Michael Blood Bob’s Findings by Robert Verish IMCA Insights by The IMCA Team Micro Visions by John Kashuba Galactic Lore by Mike Gilmer Meteorite Calendar by Anne Black Meteorite of the Month by Michael Johnson Tektite of the Month by Editor Terms Of Use Materials contained in and linked to from this website do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of The Meteorite Exchange, Inc., nor those of any person connected therewith. In no event shall The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be responsible for, nor liable for, exposure to any such material in any form by any person or persons, whether written, graphic, audio or otherwise, presented on this or by any other website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website. The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. does not endorse, edit nor hold any copyright interest in any material found on any website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website. The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. shall not be held liable for any misinformation by any author, dealer and or seller. In no event will The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be liable for any damages, including any loss of profits, lost savings, or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, consequential, or other damages arising out of this service. © Copyright 2002–2010 The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. All rights reserved. No reproduction of copyrighted material is allowed by any means without prior written permission of the copyright owner. -

Naretha Meteorite (Synonyms Kingoonya, Kingooya)

Rec. West. Aust. Mus., 1976, 4 (1) NARETHA METEORITE (Sync;>nyms: Kingoonya, Kingooya) W.H. CLEVERLY* [Received 27 May 1975. Accepted 1 October 1975. Published 31 August 1976.1 ABSTRACT Much of the missing portion of the Naretha (Western Australia) meteorite has been located in museums as an un-named specimen and as two smaller specimens masquerading under the name 'Kingoonya' (or 'Kingooya'). The use of the junior synonyms with their implications of a South Australian site of find should be discontinued. INTRODUCfION Naretha meteorite, an L4 chondrite, was found in 1915 about 3 km north of the 205-mile station during construction of the Trans-Australian Railway. It was broken into at least three major pieces which were acquired by Mr John Darbyshire, Supervising Engineer for the construction of the western end of the railway (construction was proceeding simultaneously from both Kalgoorlie and Port Augusta ends - Fig. 1). Mr Darbyshire donated the meteorite to the W.A. School of Mines in Kalgoorlie where one' piece was retained and exhibited with a photograph of the reassembled meteorite (Fig. 2). A second fragment which was passed on to the Geological Survey of Western Australia was noted briefly by Simpson (1922) who first used the name 'Naretha', the name which had been given to the 205-mile station. There is strong presumptive evidence that the third fragment was passed on to Mr S.F.C. Cook of Kalgoorlie, a private collector from whose inaccurate verbal statements and undocumented collection, the subsequent confusion arose. In late 1926 Mr Cook gave a small piece of 'meteorite to Mr G.W.