Building a Government of Laws: Adams and Jefferson 1776–1779 James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Adams Contemporaries

17 150-163 Found2 AK 9/13/07 11:27 AM Page 150 Answer Key John Adams contemporaries. These students may point out that Adams penned defenses Handout A—John Adams of American rights in the 1770s and was (1735–1826) one of the earliest advocates of colonial 1. Adams played a leading role in the First independence from Great Britain. They Continental Congress, serving on ninety may also mention that his authorship committees and chairing twenty-five of of the Massachusetts Constitution and these.An early advocate of independence Declaration of Rights of 1780 makes from Great Britain, in 1776 he penned him a champion of individual liberty. his Thoughts on Government, describing 5. Some students may suggest that gov- how government should be arranged. ernment may limit speech when the He headed the committee charged public safety requires it. Others may with writing the Declaration of Inde- suggest that offensive or obscene pendence. He served on the commis- speech may be restricted. Still other sion that negotiated the Treaty of Paris, students will argue against any limita- which ended the Revolutionary War. tions on freedom of speech. 2. Adams was not present at the Consti- tutional Convention. However, while serving as an American diplomat in Handout B—Vocabulary and London, he followed the proceedings. Context Questions Adams and Jefferson urged Congress 1. Vocabulary to yield to the Anti-Federalist demand a. disagreed for the Bill of Rights as a condition for b. caused ratifying the proposed Constitution. c. until now 3. The Alien and Sedition Acts gave the d. -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

Interpreting an Unamendable Text Thomas W

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 4 3-2018 Interpreting an Unamendable Text Thomas W. Merrill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Administrative Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas W. Merrill, Interpreting an Unamendable Text, 71 Vanderbilt Law Review 547 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol71/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interpreting an Unamendable Text Thomas W. Merrill* 'A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation." -Edmund Burke' Many of the most important legal texts in the United States are highly unamendable. This applies not only to the Constitution, which has not been amended in over forty years, but also to many framework statutes, like the Administrative Procedure Act and the Sherman Antitrust Act. The problem is becoming increasingly severe, as political polarization makes amendment of these texts even more unlikely. This Article considers how interpreters should respond to highly unamendable texts. Unamendable texts have a number of pathologies, such as excluding the people and their representatives from any direct participation in legal change. They also pose an especially difficult problem for interpreters,since the interpretercannot rely on the implicit ratificationof its efforts that comes about when an enacting body reviews and does not amend the efforts of the interpreter. -

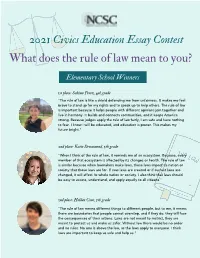

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

The Stamp Act Crisis (1765)

Click Print on your browser to print the article. Close this window to return to the ANB Online. Adams, John (19 Oct. 1735-4 July 1826), second president of the United States, diplomat, and political theorist, was born in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts, the son of John Adams (1691-1760), a shoemaker, selectman, and deacon, and Susanna Boylston. He claimed as a young man to have indulged in "a constant dissipation among amusements," such as swimming, fishing, and especially shooting, and wished to be a farmer. However, his father insisted that he follow in the footsteps of his uncle Joseph Adams, attend Harvard College, and become a clergyman. John consented, applied himself to his studies, and developed a passion for learning but refused to become a minister. He felt little love for "frigid John Calvin" and the rigid moral standards expected of New England Congregationalist ministers. John Adams. After a painting by Gilbert Stuart. Adams was also ambitious to make more of a figure than could Courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC- USZ62-13002 DLC). be expected in the local pulpits. So despite the disadvantages of becoming a lawyer, "fumbling and racking amidst the rubbish of writs . pleas, ejectments" and often fomenting "more quarrels than he composes," enriching "himself at the expense of impoverishing others more honest and deserving," Adams fixed on the law as an avenue to "glory" through obtaining "the more important offices of the State." Even in his youth, Adams was aware he possessed a "vanity," which he sought to sublimate in public service: "Reputation ought to be the perpetual subject of my thoughts, and the aim of my behaviour." Adams began reading law with attorney James Putnam in Worcester immediately after graduation from Harvard College in 1755. -

Part One the Road to the Presidency

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51421-7 - William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative Jonathan Lurie Excerpt More information Part One THE ROAD tO tHE PrESIDENCY © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51421-7 - William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative Jonathan Lurie Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51421-7 - William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative Jonathan Lurie Excerpt More information 1 The Early Years, 1857–1887 At Home with Alphonso and Louisa Chartered as a village in 1802 and incorporated as a city in 1819, Cincinnati by 1843 had become a typical Midwestern urban center. Already the city fea- tured macadamized roads, a canal and railroad system, and a bustling water- front replete with daily arrivals of cargo and passengers. In mid-century, it was home to meat packers, brewers, dry goods merchants, book sellers, printers and publishers, physicians, and above all, lawyers, who easily outnumbered all the other occupations. Names such as Wurlitzer, Proctor, and Gamble attested to the city’s success as a magnet for new commercial enterprise, while, increas- ingly, well-known politicians such as Salmon P. Chase affirmed its relevance as a community replete with significant discussions/meetings on national political issues such as the tariff, internal improvements, temperance, abolition, and the looming threat of civil war. By the 1870s, its population had reached more than 200,000.1 Numerous houses of worship dotted the greater Cincinnati area, and the city even boasted of a growing line of suburbs that had sprung up among the seven hills that surrounded the downtown area.2 One of these suburbs was known as Mt. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law. -

A Republican Abroad: John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 A Republican Abroad: John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution Robert Wilmer Smith College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Robert Wilmer, "A Republican Abroad: John Adams and the Diplomacy of the American Revolution" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625694. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ggdh-n397 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REPUBLICAN ABROAD: JOHN ADAMS AND THE DIPLOMACY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfilment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Robert W. Smith, Jr. 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Robert W.Smith, Jy. Approved, April 1991 Joh: . Selbv Edward P. Crapcjl Thomas F. Sheppa TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................ iv ABSTRACT......................................... v INTRODUCTION.....................................2 PART I. A VIRTUOUS REPUBLIC.....................5 PART II. A COMMERCIAL REPUBLIC................ 16 PART III. THE DIPLOMACY OF A SHORT WAR......... 27 PART IV. JOHN ADAMS IN PARIS...................38 PART V. -

18-966 Department of Commerce V. New York (06/27

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2018 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ET AL. v. NEW YORK ET AL. CERTIORARI BEFORE JUDGMENT TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT No. 18–966. Argued April 23, 2019—Decided June 27, 2019 In order to apportion congressional representatives among the States, the Constitution requires an “Enumeration” of the population every 10 years, to be made “in such Manner” as Congress “shall by Law di- rect,” Art. I, §2, cl. 3; Amdt. 14, §2. In the Census Act, Congress del- egated to the Secretary of Commerce the task of conducting the de- cennial census “in such form and content as he may determine.” 13 U. S. C. §141(a). The Secretary is aided by the Census Bureau, a sta- tistical agency in the Department of Commerce. The population count is also used to allocate federal funds to the States and to draw electoral districts. The census additionally serves as a means of col- lecting demographic information used for a variety of purposes. There have been 23 decennial censuses since 1790. All but one be- tween 1820 and 2000 asked at least some of the population about their citizenship or place of birth. -

American Political Thought, Spring 2019

San José State University Department of Political Science POLS 163, American Political Thought, Spring 2019 Course and Contact Information Instructor: Kenneth B. Peter Office Location: Clark 449 Telephone: (408) 924-5562 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday 2-4, Wednesday 12-1 (selected Wednesdays 2-3 instead), and by appointment Class Days/Time: Monday and Wednesday 10:30-11:45 Classroom: DMH 149A Canvas learning management system Course materials can be found on the Canvas learning management system course website. You can learn how to access this site at this web address: http://www.sjsu.edu/at/ec/canvas/ Course Description This course: Many of the political ideas which Americans take for granted were once new and controversial. This course seeks to reawaken the great debates which shaped our political heritage. American political theory is very different from the more famous tradition of European political theory. While APT has important European roots, it also reflects the unique historical and cultural circumstances of America. For example, Americans have tended to be suspicious of abstract theory (maybe this includes you!) As a result, APT tends to be less abstract, less idealistic, and more practical than European theory. Furthermore, the American experiment was faced from the start with an intense debate over inclusion--who would be included as citizens? The presence of slaves and Native Americans in a nation that was initially dominated by European colonizers led to contradictions within their political theories which they sought to suppress, to explain, or to reform. American Political Thought, Spring 2018 Page 1 of 21 This course focuses primarily on the American constitutional founding period.