Colorado WIC Formula Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studia O Poezji I Prozie Oświecenia Author: Bożena Mazurkowa Citation

Title: Z potrzeby chwili i ku pamięci... : studia o poezji i prozie Oświecenia Author: Bożena Mazurkowa Citation style: Mazurkowa Bożena. (2019). Z potrzeby chwili i ku pamięci... : studia o poezji i prozie Oświecenia. Kraków : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Wydanie książki dofinansowane ze środków Uniwersytetu Śląskiego w Katowicach. Książka udostępniona w otwartym dostępie na podstawie umowy między Uniwersytetem Śląskim a wydawcą. Książkę możesz pobierać z Repozytorium Uniwersytetu Śląskiego i korzystać z niej w ramach dozwolonego użytku. Aby móc umieścić pliki książki na innym serwerze, musisz uzyskać zgodę wydawcy (możesz jednak zamieszczać linki do książki na serwerze Repozytorium Uniwersytetu Śląskiego). Książka Bożeny Mazurkowej BOŻENA MAZURKOWA ma wymiar monograficzny. Zawarte w niej rozprawy scala naczelna idea skupienia się na faktach literackich z zakresu twórczości publiczno-okolicznościowej i osobisto-okazjonalnej. Wypada stwierdzić, CHWILIZ POTRZEBY I KU PAMIĘCI... że Bożena Mazurkowa doskonale porusza się w obrębie podjętej problematyki i przedstawionym zbiorem wkracza w grono czołowych badaczy oświeceniowej literatury okolicznościowej. Wszystkie rozprawy mają charakter nowatorski, dotyczą materii ważnych, godnych pilnej, dokładnej analizy. Książka Bożeny Mazurkowej BOŻENA MAZURKOWA Z potrzeby chwili i ku pamięci… rozprawy rozprawy Studia o poezji literackie literackie Z POTRZEBY CHWILI i prozie oświecenia w sposób istotny dopełni I KU PAMIĘCI... naszą wiedzę o rzeczywistości społeczno-literackiej tej epoki. -

The Practice of Gastrointestinal Motility Laboratory During COVID-19 Pandemic

J Neurogastroenterol Motil, Vol. 26 No. 3 July, 2020 pISSN: 2093-0879 eISSN: 2093-0887 https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20107 JNM Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility Review The Practice of Gastrointestinal Motility Laboratory During COVID-19 Pandemic: Position Statements of the Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association (ANMA-GML-COVID-19 Position Statements) Kewin T H Siah,1,2* M Masudur Rahman,3 Andrew M L Ong,4,5 Alex Y S Soh,1,2 Yeong Yeh Lee,6,7 Yinglian Xiao,8 Sanjeev Sachdeva,9 Kee Wook Jung,10 Yen-Po Wang,11 Tadayuki Oshima,12 Tanisa Patcharatrakul,13,14 Ping-Huei Tseng,15 Omesh Goyal,16 Junxiong Pang,17 Christopher K C Lai,18 Jung Ho Park,19 Sanjiv Mahadeva,20 Yu Kyung Cho,21 Justin C Y Wu,22 Uday C Ghoshal,23 and Hiroto Miwa12 1Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, The National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 3Department of Gastroenterology, Sheikh Russel National Gastroliver Institute and Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh; 4Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 5Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 6School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia; 7St George and Sutherland Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Kogarah, NSW, Australia; 8Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China; 9Department of Gastroenterology, GB Pant Hospital, New Delhi, India; -

Enviro-Watch

Issue 8 Autumn/Winter 2012 H.M.Government of Gibraltar Department of the Enviro -Watch Environment Be Waste Wise This Christmas In this issue: Be Waste Wise this Christmas Take note of what is being thrown away... Be Waste Wise this 1 Do you ever think about the amount of Christmas waste you throw out each day? How What materials take up the most about each week? Even more at space? Is anything reusable or Reducing Waste over 1 Christmas? And imagine how much you the Holidays reparable? throw away in an entire year! Recycling Facts 2 Think about reducing the number of Not only food, but paper, clothes, disposable products you use. magazines, plastic bottles, electronic Paper & Plastic 2 equipment etc., - all of this has to be Substitute products and packaging for Recycling disposed of! ones made of reusable, recyclable or non-hazardous materials. How to Produce Less 2 One of the most efficient Waste measures we can take Plan meals in advance and only buy what you need to reduce food waste. Recycling Bin 3 when it comes to waste Locations management, is to We can all start taking small steps to produce less waste in reduce the amount of waste we throw Map 4 the first place. away. New Year Green Resolutions: Reducing Waste over the Holidays I will use my car less Christmas Cards Christmas Food and walk more. This year why not try e-cards or reduce Plan meals in advance to use the food I will recycle more. cards by sending one per family. -

Introducing New Reclosable Packaging! from Nestlé Health Science All Tetra Briks® Are Moving to Reclosable Tetra Prisma® Across the Entire Portfolio of Products

Introducing New Reclosable Packaging! from Nestlé Health Science All Tetra Briks® are moving to reclosable Tetra Prisma® across the entire portfolio of products. ✔ Easy to Open ✔ Convenient Reclosable Cap ✔ Comfortable Grip ✔ Recycle Cartons with the Cap On New Tetra Prisma® Cartons with a Reclosable Cap! • Convenient Recloseable Cap: • Removal of Plastic Straws: Makes it easy to open the product With the change to a reclosable, recyclable and allows for remaining formula to cap, it is estimated that 125 million straws be easily reclosed and stored in the will be eliminated on an annual basis. refrigerator for up to 24 hours. • Easy to Grip: • Recycle Cartons with Cap On: The prismatic shape fits perfectly in hands of many sizes for a comfortable grip All new packaging will contain the during consumption or pouring. “how2recycle.com” logo, which is a standardized labeling system that • Supporting Sustainable Forestry: clearly helps communicate recycling The Tetra Prisma® is made mainly instructions to the consumer. from paper, a renewable resource, and is available with FSC™ (Forest Stewardship Council™) certified packaging material, ensuring that the wood fiber is sourced from responsibly managed forests and other controlled sources.1 Follow us at #nestleusa.com/sustainability to learn more about Nestlé’s sustainable packaging initiatives. What’s Changing? What’s Staying the Same? • Case Pack: ✔ Same great taste All cases will go from 27 count to 24 servings per case ✔ Volume/carton (237 mL/8 fl oz) • Case Specifications: The case UPC and product codes have changed, along with ✔ NDC numbers and each UPC codes* case/pallet configurations and weights. -

Packaging Influences on Olive Oil Quality: a Review of the Literature

Report Packaging influences on olive oil quality: A review of the literature Selina Wang, PhD, Xueqi Li, Rayza Rodrigues and Dan Flynn August 2014 Copyright © 2014 UC Regents, Davis campus. All rights reserved. Photo: iStockphoto/danr13 Packaging influences on Olive Oil Quality – UC Davis Olive Center, August 2014 Packaging Influences on Olive Oil Quality: A Review of the Literature Extra virgin olive oil is a fresh juice extracted from olive fruits. As with other fruit juices, the freshness and flavor quality of olive oil diminish with time, and the rate of deterioration is influenced by packaging type. To maximize shelf stability, the ideal packaging material would prevent light and air penetration, and the oils would be stored in the dark at 16 – 18 °C (61 – 64 °F). Table 1 indicates how chemical components in olive oil influence the shelf life of the oil. Table 1. How chemical components in the oil can influence shelf life Chemical component Effect on the shelf life Fatty acid profile High level of polyunsaturated fats such as linoleic acid and linolenic acid shortens shelf life; high level of saturated fats such as stearic acid and palmitic acid helps to prolong shelf life. Free fatty acidity Free fatty acids promote oxidation and shorten shelf life. Peroxide value High level of peroxide value shortens shelf life. Trace metals Trace metals promote oxidation and shorten shelf life. Oxygen Oxygen promotes oxidation and shortens shelf life. Moisture Moisture promotes oxidation and shortens shelf life. Phenolic content Phenolics are antioxidants and help to prolong shelf life. While a high quality olive oil under ideal storage conditions can be stored for months, even years, without becoming rancid, oxidation ultimately will lead to rancid flavors and aromas. -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Tetra Pak Story

Example Tetra Pak story New packaging is easier for users with reduced dexterity Tetra Pak has developed new packaging for fluid milk products. The one litre unit, dubbed Tetra Brik Edge 1000, is designed for consumers of all ages—from young to old. The Tetra Brik Edge is particularly welcomed by groups with reduced dexterity, but is also very much appreciated by other consumers. In addition, its production requires less plastic than other one-litre beverage carton. Consumers want more user-friendly packaging Elderly people represent a growing portion of the consumer research in Sweden, 30% of the population—including children market. Other groups with a reduced dexterity—such as chil- and the elderly—has trouble due to insufficient strength in their dren and arthritis patients—represent an increasingly impor- hands. Arthritis patients even account for 17% of the population, tant target group for food producers. ‘The buying behaviour of and their share is increasing. We must therefore take their specific these groups has an ever greater impact,’ says Gabriella Tomolillo, requirements and expectations into account.’ Product Communications Manager at Tetra Pak. ‘According to Small elements for additional convenience In order to meet this trend, Tetra The result is a beverage carton featuring a sloped upper sur- Pak developed a new one-litre face and a large screw cap. Gabriella Tomolillo lists its various package in 2009, the Tetra Brik benefits: ‘The cap has a 34 mm diameter and a ridged edge that Edge 1000. ‘We wanted a pack- requires less force when opening and closing it. Removing the age that is also perfectly suitable membrane also requires less effort. -

Biodegradable Esophageal Stents for the Treatment of Refractory Benign Esophageal Strictures

INVITED REVIEW Annals of Gastroenterology (2020) 33, 1-8 Biodegradable esophageal stents for the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures Paraskevas Gkolfakisa, Peter D. Siersemab, Georgios Tziatziosc, Konstantinos Triantafyllouc, Ioannis S. Papanikolaouc Erasme University Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium; Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; “Attikon” University General Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Abstract This review attempts to present the available evidence regarding the use of biodegradable stents in refractory benign esophageal strictures, especially highlighting their impact on clinical success and complications. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, using the terms “biodegradable” and “benign”; evidence from cohort and comparative studies, as well as data from one pooled analysis and one meta-analysis are presented. In summary, the results from these studies indicate that the effectiveness of biodegradable stents ranges from more than one third to a quarter of cases, fairly similar to other types of stents used for the same indication. However, their implementation may reduce the need for re-intervention during follow up. Biodegradable stents also seem to reduce the need for additional types of endoscopic therapeutic modalities, mostly balloon or bougie dilations. Results from pooled data are consistent, showing moderate efficacy along with a higher complication rate. Nonetheless, the validity of these results is questionable, given the heterogeneity of the studies included. Finally, adverse events may occur at a higher rate but are most often minor. The lack of high-quality studies with sufficient patient numbers mandates further studies, preferably randomized, to elucidate the exact role of biodegradable stents in the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures. -

Advances in Flexible Endoscopy

Advances in Flexible Endoscopy Anant Radhakrishnan, DVM KEYWORDS Flexible endoscopy Minimally invasive procedures Gastroduodenoscopy Minimally invasive surgery KEY POINTS Although some therapeutic uses exist, flexible endoscopy is primarily used as a diagnostic tool. Several novel flexible endoscopic procedures have been studied recently and show prom- ise in veterinary medicine. These procedures provide the clinician with increased diagnostic capability. As the demand for minimally invasive procedures continues to increase, flexible endos- copy is being more readily investigated for therapeutic uses. The utility of flexible endoscopy in small animal practice should increase in the future with development of the advanced procedures summarized herein. INTRODUCTION The demand for minimally invasive therapeutic measures continues to increase in hu- man and veterinary medicine. Pet owners are increasingly aware of technology and diagnostic options and often desire the same care for their pet that they may receive if hospitalized. Certain diseases, such as neoplasia, hepatobiliary disease, pancreatic disease, and gastric dilatation–volvulus, can have significant morbidity associated with them such that aggressive, invasive measures may be deemed unacceptable. Even less severe chronic illnesses such as inflammatory bowel disease can be asso- ciated with frustration for the pet owner such that more immediate and detailed infor- mation regarding their pet’s disease may prove to be beneficial. Minimally invasive procedures that can increase diagnostic and therapeutic capability with reduced pa- tient morbidity will be in demand and are therefore an area of active investigation. The author has nothing to disclose. Department of Internal Medicine, Bluegrass Veterinary Specialists 1 Animal Emergency, 1591 Winchester Road, Suite 106, Lexington, KY 40505, USA E-mail address: [email protected] Vet Clin Small Anim 46 (2016) 85–112 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2015.08.003 vetsmall.theclinics.com 0195-5616/16/$ – see front matter Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. -

1 Dr. Melody Joy V. Mique Biochemistry of Digestion 2

DR. MELODY JOY V. MIQUE BIOCHEMISTRY OF DIGESTION 2 UNIT IV BIOCHEMISTRY OF DIGESTION 2 OBJECTIVE: 1. Explain the chemical reactions involved in the process of digestion. 2. Analyze certain basic biochemical processes to explain commonly occurring health- related problems in digestion 3. Discuss the digestion of complex biomolecules in the body; TOPICS Unit 4: BIOCHEMISTRY OF DIGESTION 3. Chemical changes in the 1. Definition and factors affecting Digestion large intestines and feces 2. Phases of Digestion a. Fermentation a. Salivary Digestion b. Putrefaction b. Gastric Digestion c. Deamination c. Intestinal Digestion d. Decarboxylation d. Pancreatic Juice e. Detoxification e. Intestinal Juice 4. Feces and its Chemical Composition f. Bile CHEMICAL CHANGES IN THE LARGE INTESTINE AND FECES, CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF FECES The large intestine, also known as colon or the the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in vertebrates. The digestive tract includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and the rectum. There are 4 major functions of the large intestine: 1. recovery of water and electrolytes (Na, Cl etc) 2. formation and temporary storage of feces 3. maintaining a resident population of over 500 species of bacteria 3. fermentation of some of the indigestible food matter by bacteria. By the time partially digested foodstuffs reach the end of the small intestine (ileum), about 80% of the water content will be absorbed by the large intestine. The colon absorbs most of the remaining water. As the remnant food material moves through the colon, it is mixed with bacteria and mucus, and formed into feces for temporary storage before being eliminated by defecation In humans, the large intestine begins in the right iliac region of the pelvis, just at or below the waist, where it is joined to the end of the small intestine at the cecum, via the ileocecal valve. -

The Level of C.Pneumoniae, Cytomegalovirus, and H.Pylori Antibody in a Patient with Coronary Heart Disease

Vol 11, No 4, October – December 2002 Microorganism antibodies in CHD patient 211 The level of C.pneumoniae, Cytomegalovirus, and H.pylori antibody in a patient with coronary heart disease Dasnan Ismail Abstrak Aterosklerosis sampai saat ini merupakan penyebab utama morbiditas dan mortalitas di negara maju. Meskipun modifikasi faktor risiko di negara maju telah dapat menurunkan kekerapan aterosklerosis namun penurunan ini mulai menunjukkan grafik yang mendatar. Keadaan ini merangsang para peneliti untuk mencari faktor pajanan lingkungan termasuk faktor infeksi yang dapat mempengaruhi proses aterosklerosis. Telah dilakukan penelitian potong lintang dari bulan Maret 1998 sampai Agustus 1998 terhadap 122 orang pasien yang secara klinis menunjukkan penyakit jantung koroner yang menjalani kateterisasi jantung, terdiri dari 92 orang laki-laki dan 30 orang perempuan dengan rerata umur 55 tahun. Pasien diperiksa secara klinis dan laboratorium (gula darah, kolesterol, trigliserida dan antibodi terhadap C.pneumoniae, Cytomegalovirus dan H.pylori). Pada penelitian ini didapatkan perbedaan kadar kolesterol, trigliserida dan HDL antara kelompok stenosis koroner dan non stenosis. Sedangkan kadar antibodi C.pneumoniae, Cytomegalovirus, H.pylori tidak berbeda bermakna. Penelitian ini belum dapat menyimpulkan pengaruh antibodi terhadap aterosklerosis karena pada kelompok non stenosis tidak dapat disingkirkan kemungkinan terjadinya aterosklerosis mengingat rerata umur subyek penelitian 55 tahun. Penelitian mengenai interaksi infeksi dengan risiko tradisional serta gender dan nutrisi diperlukan untuk mendapat jawaban yang lebih jelas tentang pengaruh infeksi terhadap aterosklerosis. (Med J Indones 2002; 11: 211-4) Abstract Atherosclerosis is still the chief cause of morbidity and mortality in developed nations. Even though in developed nations the modification of risk factors is able to reduce the prevalence rate of atherosclerosis, such reduction is starting to slow down. -

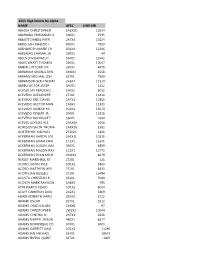

15E5 Ssgt Selects by Alpha

15E5 SSgt Selects by Alpha NAME AFSC LINE-NR ABADIA CHRISTOPHER 2A5X2D 10234 ABARAWA EMMANUEL K 3S0X1 1595 ABBOTT DANIEL PATR 2A7X3 10224 ABDULLAH MALIZIO J 3P0X1 7420 ABENDROTH MARIE CH 00XXX 11386 ABESAMIS CHAMAL JA 2S0X1 44 ABLES LOVIEANGELO 3S0X1 11062 ABLES WYATT THOMAS 2S0X1 10007 ABNER CLIFFORD LEE 3P0X1 4479 ABRAHAM SHARLA DEN 3M0X1 3558 ABRAMS MICHAEL JOH 3E7X1 7500 ABRAMSON SETH NEWM 2A6X4 11510 ABREU VICTOR JOSEP 3P0X1 1412 ACASIO JAY PEROCHO 1P0X1 8032 ACEVEDO ALEXANDER 2T3X1 11416 ACEVEDO ERIC DAVID 2A7X1 12965 ACEVEDO HECTOR MAN 1A0X1 11303 ACEVEDO JANIECE PA 3D0X1 13070 ACEVEDO ROBERT JR 2F0X1 11918 ACEVEDO RODRIGUEZ 3S0X1 2680 ACEVES ULYSSES ALE 2A3X4A 1056 ACHESON SHON THOMA 2A8X2B 5382 ACHTERHOF MICHAEL 2T3X2C 1821 ACKERMAN AARON JOS 2A3X3L 10231 ACKERMAN ADAM CRAI 1C1X1 11641 ACKERMAN LOGAN JAM 3P0X1 8889 ACKERMAN MASON RAY 1C3X1 12772 ACKERMAN RYAN MICH 2M0X3 8079 ACKLEY MARSHALL RY 2T2X1 321 ACORD JUSTIN KYLE 3D1X2 5960 ACORD MATTHEW WILL 2T2X1 5433 ACORN IAN RUSSELL 2T1X1 12494 ACOSTA CHRISTIAN R 3E3X1 7080 ACOSTA MARK RAYMON 2A6X2 495 ACRI MARCO ELIGIO 3D1X2 8009 ACUFF CAMERON DAVI 2A2X1 6869 ADAIR KENNETH HARO 3D0X2 8722 ADAME OSCAR 3E7X1 1512 ADAMS CHAD KALANI 2A6X6 97 ADAMS CHRISTOPHER 2W1X1 10004 ADAMS CYNTHIA N 2A7X3 2658 ADAMS DARRYL JEMON 4B0X1 5627 ADAMS DOMINIQUE CO 3P0X1 3003 ADAMS GARRETT DAVI 3D1X3 11290 ADAMS IAN MICHAEL 3E4X1 10643 ADAMS IRVING QUINT 3E7X1 3407 ADAMS JAMES COLBY 2T3X1 2522 ADAMS JASON ROBERT 1U0X1 7795 ADAMS JOSEPH AARON 2A9X2E 2595 ADAMS KEITH JR 3P0X1 2642 ADAMS KYLE EDWARD 3D0X2