The Impact of Mining Development on Settlement Patterns, Firewood Availability and Forest Structure in Porgera JERRY K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Nothofagus, Key Genus of Plant Geography, in Time

Nothofagus, key genus of plant geography, in time and space, living and fossil, ecology and phylogeny C.G.G.J. van Steenis Rijksherbarium, Leyden, Holland Contents Summary 65 1. Introduction 66 New 2. Caledonian species 67 of and Caledonia 3. Altitudinal range Nothofagus in New Guinea New 67 Notes of 4. on distribution Nothofagus species in New Guinea 70 5. Dominance of Nothofagus 71 6. Symbionts of Nothofagus 72 7. Regeneration and germination of Nothofagus in New Guinea 73 8. Dispersal in Nothofagus and its implications for the genesis of its distribution 74 9. The South Pacific and subantarctic climate, present and past 76 10. The fossil record 78 of in time and 11. Phylogeny Nothofagus space 83 12. Bi-hemispheric ranges homologous with that of Fagoideae 89 13. Concluding theses 93 Acknowledgements 95 Bibliography 95 Postscript 97 Summary Data are given on the taxonomy and ecology of the genus. Some New Caledonian in descend the lowland. Details the distri- species grow or to are provided on bution within New Guinea. For dominance of Nothofagus, and Fagaceae in general, it is suggested that this. Some in New possibly symbionts may contribute to notes are made onregeneration and germination Guinea. A is devoted a discussion of which to be with the special chapter to dispersal appears extremely slow, implication that Nothofagus indubitably needs land for its spread, and has needed such for attaining its colossal range, encircling onwards of New Guinea the South Pacific (fossil pollen in Antarctica) to as far as southern South America. Map 1. An is other chapter devoted to response ofNothofagus to the present climate. -

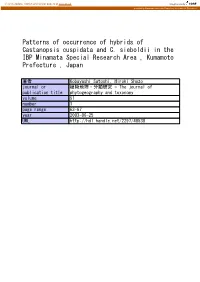

Patterns of Occurrence of Hybrids of Castanopsis Cuspidata and C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kanazawa University Repository for Academic Resources Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan 著者 Kobayashi Satoshi, Hiroki Shozo journal or 植物地理・分類研究 = The journal of publication title phytogeography and toxonomy volume 51 number 1 page range 63-67 year 2003-06-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2297/48538 Journal of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 51 : 63-67, 2003 !The Society for the Study of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 2003 Satoshi Kobayashi and Shozo Hiroki : Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan Graduate School of Human Informatics, Nagoya University, Chikusa-Ku, Nagoya 464―8601, Japan Castanopsis cuspidata(Thunb.)Schottky and However, it is difficult to identify the hybrids by C. sieboldii(Makino)Hatus. ex T. Yamaz. et nut morphology alone, because the nut shapes of Mashiba are dominant components of the ever- the 2 species are variable and can overlap with green broad-leaved forests of southwestern Ja- each other. Kobayashi et al.(1998)showed that pan, including parts of Honshu, Kyushu and hybrids have a chimeric structure of both 1 and Shikoku but excluding the Ryukyu Islands(Hat- 2 epidermal layers within a leaf. These morpho- tori and Nakanishi 1983).Although these 2 Cas- logical differences among C. cuspidata, C. sie- tanopsis species are both climax species, it is boldii and their hybrid can be confirmed by ge- very difficult to distinguish them because of the netic differences in nuclear species-specific existence of an intermediate type(hybrid). -

Ray Imaging of a Dichasium Cupule of Castanopsis from Eocene Baltic Amber

RESEARCH ARTICLE Synchrotron X- ray imaging of a dichasium cupule of Castanopsis from Eocene Baltic amber Eva-Maria Sadowski1,4 , Jörg U. Hammel2 , and Thomas Denk3 Manuscript received 30 May 2018; revision accepted 6 September PREMISE OF THE STUDY: The Eocene Baltic amber deposit represents the largest 2018. accumulation of fossil resin worldwide, and hundreds of thousands of entrapped 1 Department of Geobiology, University of Göttingen, arthropods have been recovered. Although Baltic amber preserves delicate plant Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany structures in high fidelity, angiosperms of the “Baltic amber forest” remain poorly studied. 2 Institute of Materials Research, Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, We describe a pistillate partial inflorescence of Castanopsis (Fagaceae), expanding the Max-Planck-Str. 1, 21502 Geesthacht, Germany knowledge of Fagaceae diversity from Baltic amber. 3 Department of Palaeobiology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden METHODS: The amber specimen was investigated using light microscopy and 4 Author for correspondence (e-mail: eva-maria.sadowski@ synchrotron- radiation- based X- ray micro- computed tomography (SRμCT). geo.uni-goettingen.de) KEY RESULTS: The partial inflorescence is a cymule, consisting of an involucre of scales Citation: Sadowski, E.-M., J. U. Hammel, and T. Denk. 2018. Synchrotron X- ray imaging of a dichasium cupule of Castanopsis that surround all four pistillate flowers, indicating a dichasium cupule. Subtending bracts from Eocene Baltic amber. American Journal of Botany 105(12): are basally covered with peltate trichomes. Flowers possess an urecolate perianth of 2025–2036. six nearly free lobes, 12 staminodia hidden by the perianth, and a tri-locular ovary that doi:10.1002/ajb2.1202 is convex- triangular in cross section. -

Assessing Restoration Potential of Fragmented and Degraded Fagaceae Forests in Meghalaya, North-East India

Article Assessing Restoration Potential of Fragmented and Degraded Fagaceae Forests in Meghalaya, North-East India Prem Prakash Singh 1,2,* , Tamalika Chakraborty 3, Anna Dermann 4 , Florian Dermann 4, Dibyendu Adhikari 1, Purna B. Gurung 1, Saroj Kanta Barik 1,2, Jürgen Bauhus 4 , Fabian Ewald Fassnacht 5, Daniel C. Dey 6, Christine Rösch 7 and Somidh Saha 4,7,* 1 Department of Botany, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong 793022, India; [email protected] (D.A.); [email protected] (P.B.G.); [email protected] (S.K.B.) 2 CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow 226001, Uttar Pradesh, India 3 Institute of Forest Ecosystems, Thünen Institute, Alfred-Möller-Str. 1, House number 41/42, D-16225 Eberswalde, Germany; [email protected] 4 Chair of Silviculture, University of Freiburg, Tennenbacherstr. 4, D-79085 Freiburg, Germany; anna-fl[email protected] (A.D.); fl[email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (J.B.) 5 Institute for Geography and Geoecology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Kaiserstr. 12, D-76131 Karlsruhe, Germany; [email protected] 6 Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 202 Natural Resources Building, Columbia, MO 65211-7260, USA; [email protected] 7 Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlstr. 11, D-76133 Karlsruhe, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: prem12fl[email protected] (P.P.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 19 September 2020 Abstract: The montane subtropical broad-leaved humid forests of Meghalaya (Northeast India) are highly diverse and situated at the transition zone between the Eastern Himalayas and Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspots. -

Tiof\Lal ORGANIZATION of PALAEOBOTANY

I p INTERN,~TIOf\lAL ORGANIZATION OF PALAEOBOTANY INTERNATlONAL UNION Of BIOLOGICAL SC1ENCES Secr"tary: Dr. M. C. BOULTER ·SECTION FOR PALAEOBOTANY N. E. London Polytechnic, ? ..sident: Prot. W.G. CHALONEI'\. UK Romfoyo Road, Vice Presidents: !>cof. c. 30UREAU, FRANCE London, E15 412. England. Dr. S. ARCHANGHSKY, ARGENTINA Dr. S.V. MEYEN, USSR DECEMBER 1'383 lOP NE\~S .......................................... REPORTS OF RECENT MEETINGS ......................... 1 FORTHCOMING ,'1EETINGS .......... , .................... 4 OBITUI\RIES ......................................... 5 REQUESTS FeR HE!...? ................................. 7 NE',.,IS OF ! ND! VI JU)1,LS ............................ " .. 7 SALES OF FOSS I LS .................................... 8 BiaLIOGRAPHIES ......... , ........................... 8 RE'/!SION OF INDI)1,N SPEC,ES OF Gl')ssopteris ......... l0 RECENT °UBL I CAT IONS ............................... .11 SOOK REV I E'WS .................... , ... , .... " ........ 11 PLEASE MAIL NEWS AND CORRESPONDENCE TO YOUR REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVE OR TO THE SECRETARY FOR THE NEXT NEWSLETTER 23. The views expressed in the newsletter are those of its correspondents and do not necessarily refiect the pOI icy of iOP. lOP NEWS Many members of lOP are behind with their pay~ent5 of dues now set at £4.00 or us~3.i)O 3 year. Please use the attached form when making your payment. If you pay in £ sterling directly to London please remember to use a cheque which can be negotiated at a London bank. I!\FOPJ-I!\L BUSINESS r;EUI~IG OF lOP, Edmonton, Canada, August 1384 ThE:r'e is to he 2n inforrlal business meeting of lOP during the seco;:d lOP conference next summer. As at ReDding in 1980 its purpose is tC give the membership a chance to 2xpress its views on how lOP is operating; the Executive Committee must be accoun:ab:e to the membership and these informal meetings are one way of achieving ·:his. -

Eocene Fagaceae from Patagonia and Gondwanan Legacy in Asian Rainforests”

Response to Comment on “Eocene Fagaceae from Patagonia and Gondwanan legacy in Asian rainforests” Peter Wilf1*, Kevin C. Nixon2, María A. Gandolfo2, N. Rubén Cúneo3 1Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 USA. 2Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium, Plant Biology Section, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 USA. 3CONICET, Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio, 9100 Trelew, Chubut, Argentina. *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Denk et al. agree that we reported the first fossil Fagaceae from the Southern Hemisphere. We appreciate their general enthusiasm for our findings, but we reject their critiques, which we find misleading and biased. The new fossils unequivocally belong to Castanopsis, and significant evidence supports our Southern Route to Asia hypothesis. We recently (1) reported two Castanopsis rothwellii fossil infructescences from the early Eocene (52 Ma) of Argentine Patagonia. These are (we maintain) the oldest fossils assigned to the genus by ca. eight million years (2, 3), and they co-occur with hundreds of fagaceous leaves indistinguishable from those of living Castanopsis. The same fossil beds contain numerous taxa whose close living relatives characteristically associate with Castanopsis in New Guinea and elsewhere, including Papuacedrus, Agathis, Araucaria Sect. Eutacta, Dacrycarpus, a Phyllocladus relative (4), Podocarpus, Retrophyllum, Ripogonum, Eucalyptus, Ceratopetalum, Gymnostoma, engelhardioid Juglandaceae, and Todea, as cited (1). Nearly all these lineages are well-known examples of the Southern Route to Asia confirmed by fossil evidence from one or more of Antarctica, Australasia, and Asia (5-7), and we concluded that Castanopsis most likely had similar biogeographic history. Castanopsis thrives on the Australian plate today in New Guinea, and its southern range is only a short distance over shallow water from Australia, with which New Guinea had frequent past land connections and biotic interchanges (8). -

Litterfall Dynamics After a Typhoon Disturbance in a Castanopsis Cuspidata Coppice, Southwestern Japan Tamotsu Sato

Litterfall dynamics after a typhoon disturbance in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice, southwestern Japan Tamotsu Sato To cite this version: Tamotsu Sato. Litterfall dynamics after a typhoon disturbance in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice, southwestern Japan. Annals of Forest Science, Springer Nature (since 2011)/EDP Science (until 2010), 2004, 61 (5), pp.431-438. 10.1051/forest:2004036. hal-00883773 HAL Id: hal-00883773 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00883773 Submitted on 1 Jan 2004 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ann. For. Sci. 61 (2004) 431–438 431 © INRA, EDP Sciences, 2004 DOI: 10.1051/forest:2004036 Original article Litterfall dynamics after a typhoon disturbance in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice, southwestern Japan Tamotsu SATOa,b* a Kyushu Research Center, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI), 4-11-16 Kurokami, Kumamoto, Kumamoto 860-0862, Japan b Present address: Department of Forest Vegetation, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI), PO Box 16, Tsukuba Norin, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan (Received 11 April 2003; accepted 3 September 2003) Abstract – Litterfall was measured for eight years (1991–1998) in a Castanopsis cuspidata coppice forest in southwestern Japan. -

Quercus and Lithocarpus

"Uqog"Vjqwijvu"qp"Gxqnwvkqpct{"cpf"Rj{nqigpgvke" Perspectives in the Oaks - Quercus and Lithocarpus J. Smartt and R.J. White, School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, United Kingdom Introduction - the family Hcicegcg Cp"korqtvcpv"lwuvkÞecvkqp"hqt"ectt{kpi"qwv"gzrgtkogpvcn"vczqpqoke"uvwfkgu"qp" c"nctig"itqwr"uwej"cu"vjg"qcmu"ku"vjg"dgnkgh"vjcv"vjgug"ecp"jgnr"vq"tguqnxg"fkhÞewnvkgu" cpf"codkiwkvkgu"yjkej"vjg"encuukecn"vczqpqoke"crrtqcejgu"ecppqv0"Vjg"qcmu"ctg"c" widely distributed and species-rich group with a complex evolutionary history, and it is therefore helpful to view our present perceptions of the oaks particularly in the dtqcfgt"eqpvgzv"qh"vjg"hcokn{"vq"yjkej"vjg{"dgnqpi0 The Fagaceae is not a large family; there are ten recognised genera (Nixon, 3;:;+0"Fagus - the beeches, Nothofagus - the southern beeches, Castanea - the chestnuts, Castanopsis and Chrysolepis - the chinkapins and two genera of oaks, Lithocarpus and Quercus. In terms of species richness, the oak genera are by far vjg"nctiguv0"Ecowu"*3;58/3;76+."kp"jgt"oqpwogpvcn"yqtm"Les Chenes, recognises 279 species of Lithocarpus and 430 of Quercus. In addition, there are 3 very small genera containing rare and possibly relict species, namely Trigonobalanus, Co- lombobalanus and Formanodendron0""Vjg"pwodgt"qh"urgekgu"ujg"tgeqipkugf"kp"vjg" other genera is 8 in Fagus, 12 in Nothofagus, 7 in Castanea and 27 in Castanopsis0 Although the actual number of species recognised by different authorities varies, vjgug"Þiwtgu"kpfkecvg"tgncvkxg"urgekgu"tkejpguu0"Qp"vjku"dcuku."qcmu"eqpuvkvwvg"vjg" -

Castanopsis Chinensis Hance (Fagaceae), a Newly Recorded Plant in Taiwan

Taiwania, 51(2): 148-151, 2006 Castanopsis chinensis Hance (Fagaceae), a Newly Recorded Plant in Taiwan (1) (1) (1,2) Fu-Shan Chou , Chun-Kuei Liao and Chih-Kai Yang (Manuscript received 5 December, 2005; accepted 24 January, 2006) ABSTRACT: Castanopsis chinensis Hance is a newly recorded species to be added to the flora of Taiwan. In this paper, a detailed description, a line drawing and color photos of the species are provided. KEY WORDS: Castanopsis chinensis, New record, Flora, Taiwan. INTRODUCTION Castanopsis chinenesis Hance, Journ. Linn. Soc. Bot. 10: 201. 1868; Huang, Zhang & Bruce, Fl. The genus Castanopsis (Don) Spach., a member China 4: 329. 1999; Huang et al., Fl. Reip. Pop. of Fagaceae, is represented by about 120 species in Sin. 22: 52. 1998. 桂林栲 Figs. 1-3 subtropical and warm temperate areas of the world (Wendy, 1994). The species number of Castanopsis Evergreen trees 10-20 m tall with trunk straight; in Taiwan has been reported by different authors as branches glabrous, puberulent when young. Leaves 8 (Li, 1963; Liu and Liao, 1976; Liao, 1991, 1996 ), lanceolate to rarely ovate, 7-18 cm long, 2.5-4 cm 9 (Chen, 1997; Yang et al., 1997), 10 (Liu, 1960; wide, glabrous, thickly chartaceous, concolorous at Liu et al., 1994) and 11 (Shen, 1984). both surfaces, base rounded to acute, margin serrate In September of 2005, we found an unknown at least from middle to apex, apex caudate; midvein species of Castanopsis at Machia, Pingtung, which and secondary veins adaxially elevated, secondary is distinctly different from any other known species veins 9-12 pairs; petioles 1-2.5 cm long. -

FAGACEAE 1. FAGUS Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 997. 1753

Flora of China 4: 314–400. 1999. 1 FAGACEAE 壳斗科 qiao dou ke Huang Chengjiu (黄成就 Huang Ching-chieu)1, Zhang Yongtian (张永田 Chang Yong-tian)2; Bruce Bartholomew3 Trees or rarely shrubs, monoecions, evergreen or deciduous. Stipules usually early deciduous. Leaves alternate, sometimes false-whorled in Cyclobalanopsis. Inflorescences unisexual or androgynous with female cupules at the base of an otherwise male inflorescence. Male inflorescences a pendulous head or erect or pendulous catkin, sometimes branched; flowers in dense cymules. Male flower: sepals 4–6(–9), scalelike, connate or distinct; petals absent; filaments filiform; anthers dorsifixed or versatile, opening by longitudinal slits; with or without a rudimentary pistil. Female inflorescences of 1–7 or more flowers subtended individually or collectively by a cupule formed from numerous fused bracts, arranged individually or in small groups along an axis or at base of an androgynous inflorescence or on a separate axis. Female flower: perianth 1–7 or more; pistil 1; ovary inferior, 3–6(– 9)-loculed; style and carpels as many as locules; placentation axile; ovules 2 per locule. Fruit a nut. Seed usually solitary by abortion (but may be more than 1 in Castanea, Castanopsis, Fagus, and Formanodendron), without endosperm; embryo large. Seven to 12 genera (depending on interpretation) and 900–1000 species: worldwide except for tropical and S Africa; seven genera and 294 species (163 endemic, at least three introduced) in China. Many species are important timber trees. Nuts of Fagus, Castanea, and of most Castanopsis species are edible, and oil is extracted from nuts of Fagus. Nuts of most species of this family contain copious amounts of water soluble tannin. -

(Fagaceae): Castaneoid Fruits from the Eocene of Vancouver Island,Canada1

American Journal of Botany 94(3): 351–361. 2007. CASCADIACARPA SPINOSA GEN. ET SP. NOV.(FAGACEAE): CASTANEOID FRUITS FROM THE EOCENE OF VANCOUVER ISLAND,CANADA1 RANDAL A. MINDELL,2 RUTH A. STOCKEY,2,4 AND GRAHAM BEARD3 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E9 Canada; and 3Vancouver Island Paleontology Museum, Qualicum Beach, British Columbia V9K 1K7 Canada Documenting the paleodiversity of well-studied angiosperm families serves to broaden their circumscription while also providing a time-specific reference point to mark the first occurrence of characters and appearance of lineages. More than 80 anatomically preserved specimens of spiny, cupulate fruits in various developmental stages have been studied from the Eocene Appian Way locality of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. Details of internal anatomy and external morphology are known for the cupules, fruits, and pedicels. Cupule spines branch and are often borne in clusters. Cupules lack clear sutures and are adnate to a single nut that is enclosed entirely with the exception of the apical stylar protrusion of the pistil. A central hollow cylinder of vascular tissue can be seen extending up the peduncle to the base of the fruit and along the inner wall of the cupule. The fruit has a sclerotic outer pericarp that grades into a parenchymatous mesocarp and a sclerotic endocarp lining the locules. Early in development, the two locules are divided by a thin septum to which the ovules are attached. Only one seed develops to maturity as evidenced by an embryo occupying the locule alongside an abortive apical ovule. Three-dimensional reconstructions of these fruits have allowed for comparisons to both extinct and extant fagaceous taxa.