O:\RSWL\ECF Ready\17-3123, Alexander V. MGM Et Al. Mtn To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 31, Number 50 Thursday, December 24, 2015

VVolumeolume 331,1, NNumberumber 5500 TThursday,hursday, DDecemberecember 224,4, 22015015 HHappyappy HolidaysHolidays THE Page 2 December 24, 2015 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 • FAX 219/879-8070 In Case Of Emergency, Dial e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] email: Classifieds - [email protected] http://www.thebeacher.com/ PRINTED WITH Published and Printed by TM Trademark of American Soybean Association THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden 911 Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills. The Beacher is also delivered to public places in Michigan City, New Buffalo, LaPorte and Sheridan Beach. Home Sweet Home For Golf Pro, Long Beach is Where He Always Wanted to Be by Kayla Weiss When Brian God- “When he came to frey left Long Beach Chesterton for the after fi nishing college, fi rst interview, he had he didn’t quite know some extra time to kill, where life would take so he decided to drive him...nor that it would around the area, to get bring him back to the a feel for the kind of only place he’s truly environment he could called home. be bringing his family Today, the resident into...and he just fell PGA Head Golf Profes- in love with the area, sional at Long Beach so much so that he de- Country Club for al- cided to accept the job most 13 years has cre- in Chesterton with- ated a life for himself out even interviewing that not only involves out in California,” he his wife, Julie, and said. -

Creed - Nato Per Combattere

Creed - Nato per combattere Creed - Nato per combattere (Creed) è un film del 2015 co-scritto e diretto da Ryan Coogler, con protagonisti Michael B. Jordan e Sylvester Stallone. Si tratta di uno spin-off della saga di Rocky, la cui storia si svolge dopo il sesto film della serie. 1 Trama Sylvester Stallone, Tessa Thompson e Michael B. Jordan durante la promozione del film al Philadelphia Art Museum. Adonis, figlio di Apollo Creed (deceduto prima della sua nascita), viaggia per Filadelfia, dove incontra Rocky Bal- boa (ex campione dei pesi massimi) nella speranza di tro- 2.1 Riprese varlo e chiedergli di essere suo allenatore e mentore, per poter diventare un pugile professionista e vincere il titolo Le riprese sono iniziate il 19 gennaio 2015 in Inghilterra, di campione con il nome del padre. dove la prima scena del film è stata girata durante l'intervallo della partita di calcio tra Everton FC e West Bromwich Albion FC al Goodison Park di Liverpool.[8][9] Le restanti riprese si sono svolte a Filadelfia.[10][11] Nei primi di febbraio, un negozio vuoto di Philadelphia viene 2 Produzione trasformato in una palestra di boxe, dove sono state girate alcune scene di allenamento.[12][13] Il 24 luglio 2013, viene annunciato che la Metro- Il 13 febbraio, la troupe del film è avvistata al The Vic- Goldwyn-Mayer ha firmato un contratto con il regista di tor Café per altre riprese.[14] Il café è stato trasformato Prossima fermata Fruitvale Station, Ryan Coogler, per di- nell'Adrian’s Restaurant, e la troupe è nuovamente avvi- rigere uno spin-off della serie di film di Rocky, che Coo- stata per le riprese lì il 16 febbraio.[15] Stallone e Jor- [1] gler co-scrive insieme a Aaron Covington. -

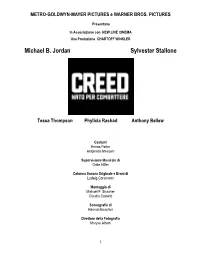

Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone

METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER PICTURES e WARNER BROS. PICTURES Presentano In Associazione con NEW LINE CINEMA Una Produzione CHARTOFF WINKLER Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone Tessa Thompson Phylicia Rashad Anthony Bellew Costumi Emma Potter Antoinette Messam Supervisione Musicale di Gabe Hilfer Colonna Sonora Originale e Brani di Ludwig Goransson Montaggio di Michael P. Shawver Claudia Castello Scenografie di Hannah Beachler Direttore della Fotografia Maryse Alberti 1 Produttore Esecutivo Nicolas Stern Prodotto da Irwin Winkler, p.g.a Robert Chartoff, p.g.a Charles Winkler William Chartoff David Winkler Kevin King-Templeton, p.g.a. Sylvester Stallone, p.g.a Soggetto di Ryan Coogler Sceneggiatura di Ryan Coogler & Aaron Covington Diretto da Ryan Coogler Distribuzione WARNER BROS. PICTURES Durata: 132 minuti Uscita italiana: 14 Gennaio 2016 I materiali sono a disposizione sul sito “Warner Bros. Media Pass”, al seguente indirizzo: https://mediapass.warnerbros.com sito: www.warnerbros.it/scheda-film/genere-azione/creed-nato-combattere FB: www.facebook.com/CreedIlFilm Ufficio Stampa Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia US Ufficio Stampa Riccardo Tinnirello Alessandro Russo [email protected] [email protected] Emanuela Semeraro Valerio Roselli [email protected] [email protected] Cinzia Fabiani [email protected] Antonio Viespoli [email protected] Egle Mugno [email protected] 2 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, Warner Bros. Pictures e New Line Cinema presentano “Creed”, del regista pluripremiato Ryan Coogler, che torna a lavorare con la star del suo “Prossima fermata Fruitvale Station”, Michael B. Jordan, nel ruolo del figlio di Apollo Creed, ed esplora un nuovo capitolo della storia di “Rocky”, con il candidato agli Oscar Sylvester Stallone nel suo ruolo storico. -

Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone

METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER PICTURES e WARNER BROS. PICTURES Presentano In Associazione con NEW LINE CINEMA Una Produzione CHARTOFF WINKLER Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone Tessa Thompson Phylicia Rashad Anthony Bellew Costumi Emma Potter Antoinette Messam Supervisione Musicale di Gabe Hilfer Colonna Sonora Originale e Brani di Ludwig Goransson Montaggio di Michael P. Shawver Claudia Castello Scenografie di Hannah Beachler Direttore della Fotografia Maryse Alberti 1 Produttore Esecutivo Nicolas Stern Prodotto da Irwin Winkler, p.g.a Robert Chartoff, p.g.a Charles Winkler William Chartoff David Winkler Kevin King-Templeton, p.g.a. Sylvester Stallone, p.g.a Soggetto di Ryan Coogler Sceneggiatura di Ryan Coogler & Aaron Covington Diretto da Ryan Coogler Distribuzione WARNER BROS. PICTURES Durata: 132 minuti Uscita italiana: 14 Gennaio 2016 I materiali sono a disposizione sul sito “Warner Bros. Media Pass”, al seguente indirizzo: https://mediapass.warnerbros.com sito: www.warnerbros.it/scheda-film/genere-azione/creed-nato-combattere FB: www.facebook.com/CreedIlFilm Ufficio Stampa Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia US Ufficio Stampa Riccardo Tinnirello Alessandro Russo [email protected] [email protected] Emanuela Semeraro Valerio Roselli [email protected] [email protected] Cinzia Fabiani [email protected] Antonio Viespoli [email protected] Egle Mugno [email protected] 2 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, Warner Bros. Pictures e New Line Cinema presentano “Creed”, del regista pluripremiato Ryan Coogler, che torna a lavorare con la star del suo “Prossima fermata Fruitvale Station”, Michael B. Jordan, nel ruolo del figlio di Apollo Creed, ed esplora un nuovo capitolo della storia di “Rocky”, con il candidato agli Oscar Sylvester Stallone nel suo ruolo storico. -

School Board Favors Reopening Slater FINAL DECISION on NEW CAMPUS PLANS SET for DEC

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Holiday Gift Guide NOVEMBER 27, 2015 VOLUME 23, NO. 44 www.MountainViewOnline.com 650.964.6300 MOVIES | 23 School board favors reopening Slater FINAL DECISION ON NEW CAMPUS PLANS SET FOR DEC. 10 By Kevin Forestieri The final decision is set for the Dec. 10 board meeting. A moun- our of the five Mountain tain of questions still remain, View Whisman School including how the district would FDistrict’s board members fund the new school and whether agreed on Nov. 19 that it’s time Google will continue to lease to open a new elementary school. a portion of the campus for For years, residents in the its day care center. Concerns northeast corner of the city over whether there are enough have decried the students to sup- lack of a neigh- port nine elemen- borhood school in ‘We are really tary schools in the Whisman and the district, both Slater neighbor- asking the financially and MICHELLE LE hood area. Since academically, are Naomi Nakano-Matsumoto is the new executive director at the Community Health Awareness the closure of community to still unaddressed. Council, one of the nonprofits serving local residents that is supported by contributions to the Voice’s Slater in 2006, the Board Presi- annual Holiday Fund. northeast “quad- do so much dent Ellen Wheel- rant” of the city er was not put has been without to open Slater.’ off by these unan- Mental health doesn’t take a holiday a local school, BOARD MEMBER BILL LAMBERT swered questions, creating a patch- and said she fully CHAC’S NEW LEADER LOOKS TO EXPAND SERVICES TO TEENS, LOW-INCOME FAMILIES work of district supports opening boundaries that send students in a school at Slater. -

{PDF} Creed Ebook, Epub

CREED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kristen Ashley | 360 pages | 15 Apr 2013 | Kristen Ashley | 9780615803876 | English | Place of publication not identified, United States Creed PDF Book Archived from the original on 4 September Retrieved February 25, Rolling Stone. December 7, Ivan Drago Florian Munteanu Undaunted, Donnie travels to Philadelphia in hopes of getting in touch with his father's old friend and rival, former heavyweight champion, Rocky Balboa. Plot Keywords. Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free! Creed disbanded in ; Stapp pursued a solo career while Tremonti, Marshall, and Phillips went on to found the band Alter Bridge with Myles Kennedy in The previous holder of this record was Justin Timberlake. His first album with the band was released in March , and is titled The Madness. If they didn't, I wouldn't be offended. Stapp and Tremonti supported the idea of Marshall going to rehab and attempted to talk Marshall into going, but he refused. Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? Archived from the original on June 27, Technical Specs. Archived from the original on September 13, Metacritic Reviews. Robert Balboa Robbie Johns He concluded that the director "offered a smart, kinetic, exhilaratingly well- crafted piece of mainstream filmmaking". Rocky Balboa Tessa Thompson Derived forms of creed creedal or credal , adjective. Archived from the original on July 2, San Francisco Film Critics Circle. Once Rocky begrudgingly gives in, things begin to coalesce. Creed is often recognized as one of the prominent acts of the post-grunge movement that began in the mids. -

AARON COVINGTON. Ref: 22533

Famous or Infamous Covingtons 12 August 2021 Return to Site Map AARON COVINGTON. Ref: 22533. Born: 5 Jun 1984 in Indiana IN. Father: not known, Father Ref: 0. Mother: not known, Mother Ref: 0. An American screenwriter and sound designer from Northwest Indiana. He attended Ohio State University and graduated from the University of Southern California in 2011 with a MFA in film production. He took part in numerous productions for the USC School of Cinematic Arts as a sound designer. Covington co-wrote the screenplay for the 2015 film Creed, a spin-off-sequel to the Rocky film series, starring Sylvester Stallone and Michael B. Jordan, with Ryan Coogler, who also directed the film. Covington is a personal friend of Coogler, and the two worked together with Stallone to green-light the film with MGM studios. Covington wrote and directed the storyline for the MyCareer mode in the video game NBA 2K17. He also worked on the US 2017 TV series "Minimum Wage". Article: 'Creed' Co-Writer to Pen 'Black Panther' Comic - January 09, 2018 7:30am by Graeme McMillan "Mario Del Pennino/Marvel Entertainment, Ryan Coogler collaborator Aaron Covington will write a two-issue storyline in 'Long Live the King.' The creatives making decisions in Wakanda are changing — for two issues, at least. Aaron Covington, who co-wrote Creed with Black Panther movie director Ryan Coogler, is joining artist Mario DelPennio for a two-issue storyline as part of Marvel’s digital Black Panther: Long Live the King comic book series. The two creators take over from Nnedi Okorafor and Andre Lima Araujo with the third issue of the series (the original pair will return for the series' final two issues to close out their storyline). -

Music.Felix@ Imperial.Ac.Uk

ISSUE 1623 FRIDAY 22nd JANUARY 2016 The Student Newspaper of Imperial College London Rewinding time in Where have all the Life Is Strange. maintenance grants gone? PAGE 10 GAMES PAGE 3 NEWS Medic boat club stopped on way to Belgium for being too drunk The annual trip to Leuven ended abruptly at Dover when students were sent home ast week’s ICSM Boat Grace Rahman the driver at 3:30am over the getting close to his legal driving arranged to fly or take the train to club’s annual trip to Editor-in-Chief students’ behaviour. The coach left limit time, this would be impossible. Leuven instead. These members got Belgium ended before it Hammersmith as scheduled at a The Dover port police were called, to their destination without a hitch. really even began – at the quarter past midnight on Saturday. to help the coach get out of the This news comes after last year’s ferry port in Dover. captain told members that “[P&O] The coach company alleges that one way system before the group shenanigans on the same club’s LCurrent medics and alumni were were willing for us to be allowed on some students caused damage at were driven back to Hammersmith. annual Leuven trip, when a coach prevented by P&O ferry staff from after a 2-3 hour wait. Unfortunately, Maidstone service station, which Upon returning, the group tried to window was smashed on the way boarding the boat which would have the coach drivers were unwilling P&O ferries confirmed. Thebook another coach in an attempt to Dover. -

In Motion 2016

THE ANNUAL PUBLICATION OF THE SCA FAMILY FALL 2016 IN MOTION Virtual Reality BeginsNATIONAL REGULAR Here REMEMBERING Kenneth Hall and Ian Sander Andrew Marlowe on CASTLE’S EPIC RUN UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Departments MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN IN MOTION FALL 2016 3 YEAR IN REVIEW 4 Dean Elizabeth M. Daley ALUMNI QUICKTAKES Senior Associate Dean, 34 Quick Read External Relations Marlene Loadvine ALUMNI TV AND FILMS 36 IN RELEASE STUDENT ACADEMY AWARDS Associate Dean of 14 Communications & PR, In Motion Managing Editor Kristin Borella IN MEMORIAM 38 DIVERSITY COUNCIL 26 Communications & Development Writer/Editor, In Motion Story Editor Desa Philadelphia Contributors Brendan Cowles Keryl Brown Stories Kacie Chow Ryan Dee Gilmour Claudia Guerra Hugh Hart Sabrina Malekzadah Matthew Meier Desa Philadelphia Justin Wilson Photographers Carell Augustus Alan Baker Ted Catanzaro Eric Charbonneau Steve Cohn Michal Czerwonka Charles Hess Board of Councilors Frank Price (Chair) SCA Takes The Lead In Creating VR Content Frank Biondi, Jr. Barry Meyer 18 Barry Diller Les Moonves Lee Gabler Sidney Poitier David Geffen Shonda Rhimes Jim Gianopulos John Riccitiello Brian T. Grazer Barney Rosenzweig Brad Grey Scott Sassa Jeffrey Katzenberg Steven Spielberg Kathleen Kennedy Kevin Tsujihara Alan Levine John Wells George Lucas Jim Wiatt Michael Lynton Paul Junger Witt Don Mattrick Robert Zemeckis Bill M. Mechanic Andrew Marlowe Alumni Reflection: MEGA: A Community Alumni Development Council Revisits His Roots Jason Michael Berman For Game Play John August -

Movie Review: ‘Creed’

Movie Review: ‘Creed’ By Kurt Jensen Catholic News Service NEW YORK – “One step, one punch, one round at a time” is the mantra of Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky Balboa in “Creed” (Warner Bros.). This seventh “Rocky” film is an imaginative and – if you can believe it – somewhat gentle reboot of the blockbuster franchise. The same patient motto sums up director Ryan Coogler’s approach to his task. In the screenplay he co-wrote with Aaron Covington, Coogler is wise enough to touch lightly on all the familiar notes of the 1976 original, thus reminding his audience that he respects the past even as he reinvents for the future. Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan) is the illegitimate son of Apollo Creed (played by Carl Weathers; the character was killed in the ring in “Rocky IV”). Adonis is determined to fulfill his destiny as a boxer. This resolve justifies just enough flashbacks to show that the kid had it tough in foster care and a series of juvenile detention facilities. He uses his fists instinctively. Indeed, even after being rescued from poverty by Creed’s last wife, Mary Anne (Phylicia Rashad), and despite a promising future in finance, Adonis knows he belongs in the ring. So he abandons weekend bouts in Tijuana and the trappings of luxury in Los Angeles for training in scruffy, cold Philadelphia. His coach, of course, is the legendary former heavyweight champ, now widowed and operating an Italian restaurant. Adonis doesn’t pummel any slabs of beef in a meat locker, but the regimen is otherwise intact: Rocky has him chasing chickens and performing one-armed pushups. -

CREED Written by Ryan Coogler and Aaron Covington Based On

CREED Written by Ryan Coogler and Aaron Covington Based on, Characters from the ROCKY Series Written by Sylvester Stallone Draft 9/30/14 1 INT. FIGHT CLUB/ BAR- TIJUANA MEXICO- DAY 1 We open on a mural of Jesus Christ, painted on the wall of the bar. We pan down to reveal dank surroundings where disinterested patrons are watching a brutal flyweight match between TWO HISPANIC FIGHTERS. 2 INT. DRESSING ROOM- FIGHT CLUB/ BAR- TIJUANA MEXICO 2 More of a water stained box where ADONIS JOHNSON (20’S, Black) leans from one side to another, attempting to stay loose. FLORES (30’s) a battle scarred Mexican fighter, stands across from Adonis, thick and menacing, with a neutral expression. Adonis glances at his opponent, who stares back emptily. The door opens off screen. REFFEREE (O.S.) Vamanos! The two fighters stand up. 3 INT. RING- FIGHT CLUB/ BAR- TIJUANA MEXICO 3 Adonis, prances around the ring, avoiding Florez who is struggling to make contact, and growing tired. Florez corners Adonis up against the ropes, and after missing a few jabs, WHAM he ducks into Adonis and lands a pretty deliberate head but above his left eye, opening a deep gash. As Adonis tries to recover: WHAM WHAM, he lands two bone crunching hooks to the gut. Adonis takes an airless breath and stumbles back to the middle of the ring, wiping blood from the gash as the bell sounds. Adonis heads to the corner, where a WAITRESS (40s) puts a stool down. He sits and she squirts water into his mouth.