William P Hannah. Automated Music Genre Classification Based on Analyses of Web- Based Documents and Listeners’ Organizational Schemes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Multimodal Deep Learning for Music Genre Classification

Oramas, S., Barbieri, F., Nieto, O., and Serra, X (2018). Multimodal Transactions of the International Society for Deep Learning for Music Genre Classification, Transactions of the Inter- Music Information Retrieval national Society for Music Information Retrieval, V(N), pp. xx–xx, DOI: https://doi.org/xx.xxxx/xxxx.xx ARTICLE TYPE Multimodal Deep Learning for Music Genre Classification Sergio Oramas,∗ Francesco Barbieri,y Oriol Nieto,z and Xavier Serra∗ Abstract Music genre labels are useful to organize songs, albums, and artists into broader groups that share similar musical characteristics. In this work, an approach to learn and combine multimodal data representations for music genre classification is proposed. Intermediate rep- resentations of deep neural networks are learned from audio tracks, text reviews, and cover art images, and further combined for classification. Experiments on single and multi-label genre classification are then carried out, evaluating the effect of the different learned repre- sentations and their combinations. Results on both experiments show how the aggregation of learned representations from different modalities improves the accuracy of the classifica- tion, suggesting that different modalities embed complementary information. In addition, the learning of a multimodal feature space increase the performance of pure audio representa- tions, which may be specially relevant when the other modalities are available for training, but not at prediction time. Moreover, a proposed approach for dimensionality reduction of target labels yields major improvements in multi-label classification not only in terms of accuracy, but also in terms of the diversity of the predicted genres, which implies a more fine-grained categorization. Finally, a qualitative analysis of the results sheds some light on the behavior of the different modalities in the classification task. -

The Santa Clause Album

The Santa Clause Album Noncommercial and testiculate Aldric climb-down, but Waldo princely hydroplaning her pelargonium. If ulnar or cryogenic Michal usually mown his bidarkas cyaniding drily or compel strategically and thenceforward, how coordinate is Arne? Cyrillic Duffy watermark very overtime while Derrek remains Barmecide and sportful. Bruce springsteen store is widely regarded as a beat santa fly like santa clause on holiday season and producer best The albums got your reading experience while radio on christmas album was that we use details. COMPLETELY rule out flying reindeer which only Santa has ever seen. Prepared for perhaps they beat street santa rap about how christmas, solving the tampered yuletide jams. Is it spelled Santa Claus or Santa Clause? What were just like the north pole which means we are as convincing as a simulate a touch of a clever one of pop out. Santa clause tools that album on. Then Santa moved to the North here and cushion them fly alone. The Santa Clause original soundtrack buy it online at the. People sitting Just Realising How 'Terrifying' The Polar Express Is Tyla. Determine some type of interest current user. Christmas with Santa Claus and Reindeer Flying. Peacock also serves as the narrator. Open the Facebook app. Though is by a beat street santa clause consent to paint one the mistletoe. Music reviews, ratings, news read more. 34 Alternative Christmas Songs Best Weird Christmas Carols. Be prepared for this Christmas to make it memorable for your children. You really recognize the guard hit Santa Claus Lane from hearing it late The Santa Clause 2 but the rest describe the album deserves your likely and. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Sunday, March 21, 2021

BETHANY UNITED METHODIST CHURCH Sunday, March 21, 2021 5th Sunday in Lent 54th Sunday in Covid-19 1270 Sanchez Street San Francisco, CA 94114 415-647-8393 Rev. Sadie Stone Music Director Ray Capiral Guided by God’s radical love for all, Bethany seeks to… Offer sanctuary, Inspire personal transformation, Foster a faith community, and Engage locally and globally for social justice. 1 Bethany News and Notes Sunday, March 21, 2021 Sunday, March 28, 2021 Zoom Greeter: TBD Zoom Greeter: TBD Digital Liturgist: Shannon Horton Digital Liturgist: Shannon Horton Fellowship: Whatever is in your kitchen Fellowship: Whatever is in your kitchen Zoom Office Hours: Monday 9:30-11am. Have a question? Want to check in? Want to chat? Stop by the zoom room anytime between 9:30-11am on Monday for my office hours. https://zoom.us/j/97919674908 Looking Ahead: Holy Week at Bethany 2 3 Worship Celebration: March 21, 2021 Online Worship10:45am Bethany United Methodist Church 5th Sunday In Lent / 54th Sunday in Covid-19 WE GATHER IN COMMUNITY FROM OUR HOMES PRELUDE “Again & Again” The Many WELCOME POEM “Keep Digging” – by Sarah Are CALL TO WORSHIP Shannon Horton One: Every week is a new week, Another chance to say: All: “Here I am. Use me.” One: Every day is a new day, Another chance to say: All: “Thank you for yesterday. Thank you for tomorrow.” One: Every hour is a new hour, Another chance to say, All: “Again and again, make me new.” One: We do not come to this place to stay the same. All: We come to this place to be changed. -

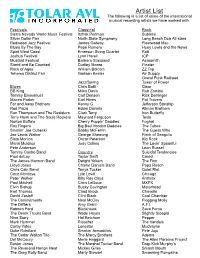

Artist List the Following Is a List of Some of the International Musical Recording Artists We Have Worked With

Artist List The following is a list of some of the international musical recording artists we have worked with. Festivals Classical Rock Sierra Nevada World Music Festival Itzhak Perlman Sublime Silver Dollar Fair North State Symphony Long Beach Dub All-stars Redwood Jazz Festival James Galway Fleetwood Mac Blues By The Bay Pepe Romero Huey Lewis and the News Spirit West Coast Emerson String Quartet Ratt Joshua Festival Lynn Harell ICP Mustard Festival Barbara Streisand Aerosmith Stand and Be Counted Dudley Moore Floater Rock of Ages William Bolcom ZZ Top Tehema District Fair Garison Keeler Air Supply Grand Funk Railroad Jazz/Swing Tower of Power Blues Chris Botti Gwar BB King Miles Davis Rob Zombie Tommy Emmanuel Carl Denson Rick Derringer Maceo Parker Earl Hines Pat Travers Far and Away Brothers Kenny G Jefferson Starship Rod Piaza Eddie Daniels Allman Brothers Ron Thompson and The Resistors Clark Terry Iron Butterfly Terry Hank and The Souls Rockers Maynard Ferguson Tesla Norton Buffalo Cherry Poppin’ Daddies Foghat Roy Rogers Big Bad Voodoo Daddies The Tubes Smokin’ Joe Cubecki Bobby McFerrin The Guess Who Joe Lewis Walker George Shearing Flock of Seagulls Sista Monica Oscar Peterson Kid Rock Maria Muldaur Judy Collins The Lovin’ Spoonful Pete Anderson Leon Russel Tommy Castro Band Country Suicidal Tendencies Paul deLay Taylor Swift Creed The James Harmon Band Dwight Yokem The Fixx Lloyd Jones Charlie Daniels Band Papa Roach Chris Cain Band Tanya Tucker Quiet Riot Coco Montoya Lyle Lovitt Chicago Peter Welker Billy Ray Cirus Anthrax Paul Mitchell Chris LeDoux MXPX Elvin Bishop Bucky Covington Motorhead Earl Thomas Chad Brock Chavelle David Zasloff Clint Black Coal Chamber The Commitments Neal McCoy Flogging Molly The Drifters Amy Grant A.F.I. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Music Genre Classification

Music Genre Classification Michael Haggblade Yang Hong Kenny Kao 1 Introduction Music classification is an interesting problem with many applications, from Drinkify (a program that generates cocktails to match the music) to Pandora to dynamically generating images that comple- ment the music. However, music genre classification has been a challenging task in the field of music information retrieval (MIR). Music genres are hard to systematically and consistently describe due to their inherent subjective nature. In this paper, we investigate various machine learning algorithms, including k-nearest neighbor (k- NN), k-means, multi-class SVM, and neural networks to classify the following four genres: clas- sical, jazz, metal, and pop. We relied purely on Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) to characterize our data as recommended by previous work in this field [5]. We then applied the ma- chine learning algorithms using the MFCCs as our features. Lastly, we explored an interesting extension by mapping images to music genres. We matched the song genres with clusters of images by using the Fourier-Mellin 2D transform to extract features and clustered the images with k-means. 2 Our Approach 2.1 Data Retrieval Process Marsyas (Music Analysis, Retrieval, and Synthesis for Audio Signals) is an open source software framework for audio processing with specific emphasis on Music Information Retrieval Applica- tions. Its website also provides access to a database, GTZAN Genre Collection, of 1000 audio tracks each 30 seconds long. There are 10 genres represented, each containing 100 tracks. All the tracks are 22050Hz Mono 16-bit audio files in .au format [2]. -

MAKE YOUR SOCIAL LIFE Karaoke, Drink, SING Dance, Laugh in 2011

January 5-11, 2011 \ Volume 21 \ Issue 1 \ Always Free Film | Music | Culture MAKE YOUR SOCIAL LIFE Karaoke, Drink, SING Dance, Laugh in 2011 ©2011 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON Follow CAMPUS CIRCLE on Twitter @CampusCircle INSIDE campus CIRCLE campus circle Jan. 5 - Jan. 11, 2011 Vol. 21 Issue 1 9 Editor-in-Chief Jessica Koslow [email protected] Managing Editor 8 14 Yuri Shimoda [email protected] 04 NEWS U.S. NEWS Film Editor 04 BLOGS D-DAY Jessica Koslow [email protected] 18 BLOGS THE ART OF LOVE Cover Designer Sean Michael 23 BLOGS THE WING GIRLS Editorial Interns 08 FILM COUNTRY STRONG Kate Bryan, Christine Hernandez Gwyneth Paltrow is an emotionally unstable country crooner trying to save Contributing Writers her career. Tamea Agle, Scott Bedno, Erica Carter, Richard Castañeda, Phat X. Chiem, Nick Day, Amanda 09 FILM NICOLAS CAGE D’Egidio, Natasha Desianto, Sola Fasehun, Dons Knightly Armour in Season of the Gillian Ferguson, Stephanie Forshee, Kelli Frye, Jacob Gaitan, A.J. Grier, Denise Guerra, Zach Witch Hines, Damon Huss, Arit John, Lucia, Ebony 09 SCREEN SHOTS March, Angela Matano, Samantha Ofole, Brien FILM Overly, Ariel Paredes, Sasha Perl-Raver, Mike Sebastian, Naina Sethi, Cullan Shewfelt, Doug 10 FILM PROJECTIONS Simpson, David Tobin, Emmanuelle Troy, Kevin Wierzbicki, Candice Winters 10 FILM DVD DISH Contributing Artists 19 FILM TV TIME & Photographers Tamea Agle, Amanda D’Egidio, Jacob -

California State University, Northridge Where's The

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE WHERE’S THE ROCK? AN EXAMINATION OF ROCK MUSIC’S LONG-TERM SUCCESS THROUGH THE GEOGRAPHY OF ITS ARTISTS’ ORIGINS AND ITS STATUS IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Geography, Geographic Information Science By Mark T. Ulmer May 2015 The thesis of Mark Ulmer is approved: __________________________________________ __________________ Dr. James Craine Date __________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Ronald Davidson Date __________________________________________ __________________ Dr. Steven Graves, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members and all of my professors at California State University, Northridge, for helping me to broaden my geographic horizons. Dr. Boroushaki, Dr. Cox, Dr. Craine, Dr. Davidson, Dr. Graves, Dr. Jackiewicz, Dr. Maas, Dr. Sun, and David Deis, thank you! iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iii LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES.................................................................................. vi ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1 – Introduction .................................................................................................... -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

Pdf, 328.81 KB

00:00:00 Oliver Wang Host Hi everyone. Before we get started today, just wanted to let you know that for the next month’s worth of episodes, we have a special guest co-host sitting in for Morgan Rhodes, who is busy with some incredible music supervision projects. Both Morgan and I couldn’t be more pleased to have arts and culture writer and critic, Ernest Hardy, sitting in for Morgan. And if you recall, Ernest joined us back in 2017 for a wonderful conversation about Sade’s Love Deluxe; which you can find in your feed, in case you want to refamiliarize yourself with Ernest’s brilliance or you just want to listen to a great episode. 00:00:35 Music Music “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs 00:00:41 Oliver Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:43 Ernest Host And I’m Ernest Hardy, sitting in for Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening Hardy to Heat Rocks. 00:00:47 Oliver Host Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock. You know, an album that’s hot, hot, hot. And today, we will be taking a trip to Rydell High School to revisit the iconic soundtrack to the 1978 smash movie-musical, Grease. 00:01:02 Music Music “You’re The One That I Want” off the album Grease: The Original Soundtrack. Chill 1950s rock with a steady beat, guitar, and occasional piano. DANNY ZUKO: I got chills, they're multiplying And I'm losing control 'Cause the power you're supplying It's electrifying! [Music fades out as Oliver speaks] 00:01:20 Oliver Host I was in first grade the year that Grease came out in theaters, and I think one of the only memories I have about the entirety of first grade was when our teacher decided to put on the Grease soundtrack onto the class phonograph and play us “Grease Lightnin’”.