Philosophy of Language in the Twenty-First Century Scott Soames Since

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sentence Types and Functions

San José State University Writing Center www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter Written by Sarah Andersen Sentence Types and Functions Choosing what types of sentences to use in an essay can be challenging for several reasons. The writer must consider the following questions: Are my ideas simple or complex? Do my ideas require shorter statements or longer explanations? How do I express my ideas clearly? This handout discusses the basic components of a sentence, the different types of sentences, and various functions of each type of sentence. What Is a Sentence? A sentence is a complete set of words that conveys meaning. A sentence can communicate o a statement (I am studying.) o a command (Go away.) o an exclamation (I’m so excited!) o a question (What time is it?) A sentence is composed of one or more clauses. A clause contains a subject and verb. Independent and Dependent Clauses There are two types of clauses: independent clauses and dependent clauses. A sentence contains at least one independent clause and may contain one or more dependent clauses. An independent clause (or main clause) o is a complete thought. o can stand by itself. A dependent clause (or subordinate clause) o is an incomplete thought. o cannot stand by itself. You can spot a dependent clause by identifying the subordinating conjunction. A subordinating conjunction creates a dependent clause that relies on the rest of the sentence for meaning. The following list provides some examples of subordinating conjunctions. after although as because before even though if since though when while until unless whereas Independent and Dependent Clauses Independent clause: When I go to the movies, I usually buy popcorn. -

The Meaning of Language

01:615:201 Introduction to Linguistic Theory Adam Szczegielniak The Meaning of Language Copyright in part: Cengage learning The Meaning of Language • When you know a language you know: • When a word is meaningful or meaningless, when a word has two meanings, when two words have the same meaning, and what words refer to (in the real world or imagination) • When a sentence is meaningful or meaningless, when a sentence has two meanings, when two sentences have the same meaning, and whether a sentence is true or false (the truth conditions of the sentence) • Semantics is the study of the meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences – Lexical semantics: the meaning of words and the relationships among words – Phrasal or sentential semantics: the meaning of syntactic units larger than one word Truth • Compositional semantics: formulating semantic rules that build the meaning of a sentence based on the meaning of the words and how they combine – Also known as truth-conditional semantics because the speaker’ s knowledge of truth conditions is central Truth • If you know the meaning of a sentence, you can determine under what conditions it is true or false – You don’ t need to know whether or not a sentence is true or false to understand it, so knowing the meaning of a sentence means knowing under what circumstances it would be true or false • Most sentences are true or false depending on the situation – But some sentences are always true (tautologies) – And some are always false (contradictions) Entailment and Related Notions • Entailment: one sentence entails another if whenever the first sentence is true the second one must be true also Jack swims beautifully. -

David Lewis on Convention

David Lewis on Convention Ernie Lepore and Matthew Stone Center for Cognitive Science Rutgers University David Lewis’s landmark Convention starts its exploration of the notion of a convention with a brilliant insight: we need a distinctive social competence to solve coordination problems. Convention, for Lewis, is the canonical form that this social competence takes when it is grounded in agents’ knowledge and experience of one another’s self-consciously flexible behavior. Lewis meant for his theory to describe a wide range of cultural devices we use to act together effectively; but he was particularly concerned in applying this notion to make sense of our knowledge of meaning. In this chapter, we give an overview of Lewis’s theory of convention, and explore its implications for linguistic theory, and especially for problems at the interface of the semantics and pragmatics of natural language. In §1, we discuss Lewis’s understanding of coordination problems, emphasizing how coordination allows for a uniform characterization of practical activity and of signaling in communication. In §2, we introduce Lewis’s account of convention and show how he uses it to make sense of the idea that a linguistic expression can come to be associated with its meaning by a convention. Lewis’s account has come in for a lot of criticism, and we close in §3 by addressing some of the key difficulties in thinking of meaning as conventional in Lewis’s sense. The critical literature on Lewis’s account of convention is much wider than we can fully survey in this chapter, and so we recommend for a discussion of convention as a more general phenomenon Rescorla (2011). -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

Perspectives on Ethical Leadership: an Overview Drs Ir Sophia Viet MTD

Perspectives on ethical leadership: an overview drs ir Sophia Viet MTD Paper submitted to the International Congress on Public and Political Leadership 2016 Draft version. Do not site or quote without the author’s permission Abstract There is a growing scientific interest in ethical leadership of organizations as public confidence in organizational leaders continues to decline. Among scholarly communities there is considerable disagreement on the appropriate way to conceptualize, define and study ethical leadership. This disagreement is partly due to the ontological and epistemological differences between the scholarly communities, resulting in different views of organizations, on the role of organizational leadership in general, and on ethical leadership of organizations in particular. Because of the differences in their ontological and epistemological assumptions scholars endlessly debate the concept of ethical leadership. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of the academic concepts of ethical leadership by classifying these concepts in terms of their ontological and epistemological assumptions and views of organizations into the modern, symbolic and the critical perspectives of postmodernism and communitarianism. Each category represents a particular set of perspectives on organizations, business ethics, and ethical leadership. The overview can serve as a guide to decode the academic debate and to determine the positions of the scholars participating in the debate. In addition it can serve as a multi-perspective-framework to study lay concepts of ethical leadership of (executive) directors of contemporary organizations. In this article the overview serves as a guide of how to classify some of the most common concepts in the debate on ethical leadership. Introduction There is a growing scientific interest in ethical leadership of organizations as public confidence in organizational leaders continues to decline. -

Lewis on Conventions and Meaning

Lewis on conventions and meaning phil 93914 Jeff Speaks April 3, 2008 Lewis (1975) takes the conventions in terms of which meaning can be analyzed to be conventions of truthfulness and trust in a language. His account may be adapted to state an analysis of a sentence having a given meaning in a population as follows: x means p in a population G≡df (1a) ordinarily, if a member of G utters x, the speaker believes p, (1b) ordinarily, if a member of G hears an utterance of x, he comes to believe p, unless he already believed this, (2) members of G believe that (1a) and (1b) are true, (3) the expectation that (1a) and (1b) will continue to be true gives members of G a good reason to continue to utter x only if they believe p, and to expect the same of other members of G, (4) there is among the members of G a general preference for people to continue to conform to regularities (1a) and (1b) (5) there is an alternative regularity to (1a) and (1b) which is such that its being generally conformed to by some members of G would give other speakers reason to conform to it (6) all of these facts are mutually known by members of G Some objections: • Clause (5) should be dropped, because, as Burge (1975) argued, this clause makes Lewis's conditions on linguistic meaning too strong. Burge pointed out that (5) need not be mutually known by speakers for them to speak a meaningful language. Consider, for example, the case in which speakers believe that there is no possible language other than their own, and hence that there is no alternative regularity to (1a) and (1b). -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

Epistemology After the Modal Turn Traditionally

Philosophy 513/Topics in Recent and Contemporary Philosophy: Epistemology after the Modal Turn Princeton University Spring 2019 Tuesdays 7-9:50 Marx 201 Professor Thomas Kelly 221 1879 Hall [email protected] Traditionally, philosophers have often given a starring role to notions like evidence and reasons for belief when theorizing about knowledge. However, in the last decades of the twentieth century and the opening decades of the twentieth-first, this traditional paradigm has been largely supplanted by alternative approaches. There are at least two complementary sources for this relatively recent, radical break with tradition. First, Edmund Gettier’s apparent refutation of “the traditional analysis of knowledge,” along with the failure of early, theoretically conservative attempts to “patch” that analysis, loosened the hold of the traditional paradigm on the philosophical imagination and created a demand for novel theoretical frameworks. More constructively, that demand for innovative approaches was met when the modal revolution, which had first entered analytic philosophy through logic and metaphysics (think Kripke, Lewis) hit epistemology. When epistemology took the modal turn, the result was an entirely new set of intriguing frameworks and powerful conceptual tools for theorizing about knowledge and related notions. Among these are the ideas that that we should think of knowledge in terms of the elimination of contextually salient possibilities (Lewis), that it consists in tracking facts (Nozick, Roush), and the increasingly influential picture of knowledge as safe belief (Williamson, Sosa). We will critically examine this currently flourishing tradition, beginning with seminal accounts by Lewis and Nozick, and continuing up to some of the latest developments. -

Freedom and Determinism (Topics in Contemporary Philosophy)

1 Determinism: What We Have Learned and What We Still Don’t Know John Earman 1 Introduction The purpose of this essay is to give a brief survey of the implications of the theories of modern physics for the doctrine of determinism. The survey will reveal a curious feature of determinism: in some respects it is fragile, re- quiring a number of enabling assumptions to give it a fighting chance; but in other respects it is quite robust and very difficult to kill. The survey will also aim to show that, apart from its own intrinsic interest, determinism is an excellent device for probing the foundations of classical, relativistic, and quantum physics. The survey is conducted under three major presuppositions. First, I take a realistic attitude toward scientific theories in that I assume that to give an interpretation of a theory is, at a minimum, to specify what the world would have to be like in order for the theory to be true. But we will see that the demand for a deterministic interpretation of a theory can force us to abandon a naively realistic reading of the theory. Second, I reject the “no laws” view of science and assume that the field equations or laws of motion of the most fundamental theories of current physics represent science’s best guesses as to the form of the basic laws of nature. Third, I take deter- minism to be an ontological doctrine, a doctrine about the temporal evo- lution of the world. This ontological doctrine must not be confused with predictability, which is an epistemological doctrine, the failure of which need not entail a failure of determinism. -

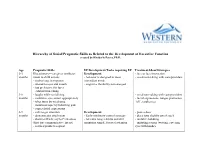

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple,