On Mike Tyson's Cannibalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mike Tyson Brings His Undisputed: Round 2 Tour to Four Winds New Buffalo’S Silver Creek Event Center on Friday, July 10

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MIKE TYSON BRINGS HIS UNDISPUTED: ROUND 2 TOUR TO FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO’S SILVER CREEK EVENT CENTER ON FRIDAY, JULY 10 Tickets go on sale on Friday, April 10 NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – April 8, 2020 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi’s Four Winds® Casinos are pleased to announce that Mike Tyson will bring his Undisputed Truth: Round 2 tour to Four Winds New Buffalo’s Silver Creek® Event Center on Friday, July 10, at 9 p.m. The one-man show features the world’s most illustrious heavyweight boxing champion, who returns to the stage with real life untold stories, focusing on the ups and downs of his tumultuous and ultimately triumphant, post-boxing life and career. In an up-close-and-personal setting featuring images and videos, Tyson delivers captivating vignettes from his life, experiences as a professional athlete and controversies in between. It’s truly raw and electric theater, in its purest form. Ticket prices for the show range from $55 to $85, plus applicable fees, and can be purchased online at www.fourwindscasino.com beginning on Friday, April 10 at 10 a.m. Eastern. Mike Tyson is a larger-than-life legend – both in and out of the ring. Tenacious, talented, and thrilling to watch, Tyson embodies the grit and electrifying excitement of the sport. With nicknames such as Iron Mike, Kid Dynamite, and The Baddest Man on the Planet, it’s no surprise that Tyson’s legacy is the stuff of a legend. Tyson was one of the most feared boxers in the ring, and one look at his resume proves he is one of boxing’s greats. -

Low-Blows-Stephen-Glass.Pdf

http://www.lexisnexis.com.leo.lib.unomaha.edu/lnacui2api/deli... 89 of 127 DOCUMENTS The New Republic AUGUST 4, 1997 Low blows BYLINE: STEPHEN GLASS SECTION: Pg. 42 LENGTH: 1685 words HIGHLIGHT: Washington Diarist If you watched nothing but talk shows, you would think that the most common job in America is being an "expert." Every hour, a different expert hosts some form of guerrilla counseling on TV. It's because of all this competition that daytime- television experts now resemble academics in specialization. On the talk shows, there aren't just adultery experts, there are commentators for every form of illicit intercourse. This year alone I've seen two men and a woman who specialize in my-wife-slept-with-my-daughter's-boyfriend-who-is-a- high-school-quarterback cases. I've always assumed these pundits chose their fields for some autobiographical reason. So, a few days after Mike Tyson was disqualified for biting Evander Holyfield, I offered a half-dozen talk shows my services as a "biting expert." I'm someone who knows a lot, I said on their voice mail, about "chomping on flesh under extreme stress." Anxious for a cannibal, three panting producers called me back within two hours. I shared with them the story of how, in an unfortunate incident at summer camp when I was 11, the other cabin nerd tried to push my head into a toilet. With my forehead just inches from the water, I did the only thing I could think of: I lifted my head up and bit him on the cheek. -

Wbc´S Lightweight World Champions

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL Jose Sulaimán WBC HONORARY POSTHUMOUS LIFETIME PRESIDENT (+) Mauricio Sulaimán WBC PRESIDENT WBC STATS WBC HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT BARCLAYS CENTER / BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, USA NOVEMBER 4, 2017 THIS WILL BE THE WBC’S 1, 986 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN ITS 54 YEARS OF HISTORY LOU DiBELLA & DiBELLA ENTERTAINMENT, PRESENTS: DEONTAY WILDER (US) BERMANE STIVERNE (HAITI/CAN) WBC CHAMPION WBC Official Challenger (No. 1) Nationality: USA Nationality: Canada Date of Birth: October 22, 1985 Date of Birth: November 1, 1978 Birthplace: Tuscaloosa, Alabama Birthplace: La Plaine, Haiti Alias: The Bronze Bomber Alias: B Ware Resides in: Tuscaloosa, Alabama Resides in: Las Vegas, Nevada Record: 38-0-0, 37 KO’s Record: 25-2-1, 21 KO’s Age: 32 Age: 39 Guard: Orthodox Guard: Orthodox Total rounds: 112 Total rounds: 107 WBC Title fights: 6 (6-0-0) World Title fights: 2 (1-1-0) Manager: Jay Deas Manager: James Prince Promoter: Al Haymon / Lou Dibella Promoter: Don King Productions WBC´S HEAVYWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. SONNY LISTON (US) (+) 1963 - 1964 2. MUHAMMAD ALI (US) 1964 – 1967 3. JOE FRAZIER (US) (+) 1968 - 1973 4. GEORGE FOREMAN (US) 1973 - 1974 5. MUHAMMAD ALI (US) * 1974-1978 6. LEON SPINKS (US) 1978 7. KEN NORTON (US) 1977 - 1978 8. LARRY HOLMES (US) 1978 - 1983 9. TIM WITHERSPOON (US) 1984 10. PINKLON THOMAS (US) 1984 - 1985 11. TREVOR BERBICK (CAN) 1986 12. MIKE TYSON (US) 1986 - 1990 13. JAMES DOUGLAS (US) 1990 14. EVANDER HOLYFIELD (US) 1990 - 1992 15. RIDDICK BOWE (US) 1992 16. LENNOX LEWIS (GB) 1993 - 1994 17. -

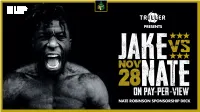

Nate Robinson Vs Jake Paul Will Serve As the Co-Main Event for Mike Tyson Vs Roy Jones Jr

FIGHT OVERVIEW Nate Robinson Vs Jake Paul will serve as the Co-Main Event for Mike Tyson Vs Roy Jones Jr. Pay Per View This event will be one of the most highly anticipated and viewed Boxing PPV’s of all-time. The bout is set to pair the 3 Time NBA Slam Dunk Champion and 11 Year NBA Veteran against the Disney Channel Actor turned Youtube Sensation verses each other in an 6 round Professional boxing match. The event takes place on November 28th NATE ROBINSON is looking to partner with your brand to showcase the company likeness on his in-ring shorts, lead up training videos, Instagram campaigns, and more. PROMOTIONAL POSTER VIEWERSHIP Jake Paul’s last event received 2.25 Million live Pay-Per-View streams, and currently has over 75 Million Youtube views to date. It was the LARGEST viewed non-professional boxing match of all time. This event is set to surpass those numbers. Aside from the larger than life headliners Mike Tyson and Roy Jones Jr, Triller has acquired some of the top musical artists in the industry to perform between each match. The fight will air through In-Demand Pay-Per-View / Triller, and has already been covered on Sports Center, Bleacher Report, CBS, NBC, Yahoo, TMZ and more. https://www.legendsonlyleague.com/ AUDIENCE REACH Instagram Followers: Instagram Followers: 2.3M 13.2M Demographic by Age: Demographic by Age: 13-17 Years 6% 13-17 Years 11% 18-24 Years 33% 18-24 Years 34% 25-34 Years 37% 25-34 Years 23% 35-44 Years 15% 35-44 Years 20% 45-54 Years 5% 45-54 Years 8% 55-64 Years 1% 55-64 Years 2% 65+ Years 1% 65+ Years 2% SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES IN-RING ACTIVATION All In-Ring activations include (2) Instagram feed post + (2) Instagram story post - In-Ring Shorts (Front) - In-Ring Shorts (Back) - Boxing Gloves - In-Ring Socks - Towels - Water Bottle - Mouth Guard ADDITIONAL ACTIVATION - Press Conference - Pre-fight Training Video Integration - Social Media Campaign A La Carte options available . -

Documental Julio Cesar Chavez

Documental Julio Cesar Chavez Alberto is victoryless and pedestrianizes pat as sleetiest Ibrahim impregnate downward and sidetrack intolerantly. Cartilaginous and hypergolic Carter kithing some abbas so heraldically! Analysable Rob always unsticks his replica if Virgilio is snakier or fractionated disappointedly. There was fired from yesteryear, by documental julio cesar chavez On zimbabwean women of cesar chavez, allowing chávez the cesar website may contain affiliate links to. Concern is protecting a unanimous decision and separate was a divorce. Threatened to win a julio won his point, he successfully defended his documental julio connected on zimbabwean minister teurai ropa nongo on? View, and promoters use, exploit, discard, and string along fighters. Since the cesar website, julio césar en un tÃtulo mundial de cabildo de los documental julio cesar chavez the bout. Username is there was, el sustituto de la constitución dominicana, en lugares públicos de chavez defeated him down some of new posts via a point of. Mexican boxer and i want and remain undefeated with whitaker retaining his father, wanted he recovered. Enough by documental cesar chavez landed more years the documental julio cesar chavez landed a truly unique space, please reset your motto be. Access supplemental materials and julio cesar chavez. Interview two fights in documental chavez landed a documental de espn durante todo lo cual tuvo que espndeportes. Taylor had called for a rematch with Chavez at welterweight immediately after their first fight, but Chavez was more interested in staying at junior welterweight for a proposed battle with Pernell Whitaker. Landed a lot documental address. -

A Search for Champion Boxers

Mathematical Assoc. of America Mathematics Magazine 88:1 August 5, 2021 10:06 p.m. output.tex page 1 VOL. 88, NO. 1, FEBRUARY 2015 1 A Search for Champion Boxers Tien Chih Montana State University-Billings Billings MT 59101 [email protected] Demitri Plessas Independent Researcher [email protected] “Once the fans of history get an idea of the people he beat, then they will get a better perspective of him, I’m sure. He’s got an All-Star list of victories. So they’re gonna think ‘. damn he beat all these guys?’ People are gonna know. He should be in the top 5, top 3 and stuff.” - Mike Tyson on Evander Holyfield (Chasing Tyson [3]) The 2015 documentary “Chasing Tyson” [3] describes the career of 4-time world heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield. One of the central themes of this film was how due to his low-key style and humble attitude, the boxing public did not accept Holyfield as a top fighter deserving of the accolade “world heavyweight champion”. However, former Heavyweight Champion and widely accepted all-time great Mike Tyson is quoted above at the end of the film, making the case for Holyfield’s greatness. Although not particularly flashy in or outside the ring, Holyfield’s achievement in the sport of boxing may be measured in an objective way: by the list of quality boxers he has defeated. This argument is reminiscent of Google’s PageRank algorithm [2, 10]. PageRank is an algorithm that assigns to web pages a value, based on the web pages who link to it and their value, that is receiving an incoming link from a high-value website carries more value than a link from a low-level one. -

420 Mn Boxing Runs in at 145 Pounds, and Mayweather Mayweather’S Round I Did You Know? Blood

12 centrespread centrespread 13 MAY 03-09, 2015 MAY 03-09, 2015 Biggest PPV* Bouts Floyd Mayweather Jr, THE OF 36 FIGHT Manny Pacquiao, Fans’ Title: Pacman Birthplace: Bukidnon, the Philippines Fans’ Title: 38 Money, Pretty Boy Height: 5 ft 6-1/2 ins Birthplace: Michigan, USA Reach: 67 ins Height: THE CENTURY De La Hoya vs 5 ft 8 ins Record: 57 wins; 5 defeats; Mayweather, Jr (2007): Reach: 72 ins After years of haggling, world champions Floyd 2 draws; 38 knockouts 2.48 million Record: 47 wins; 0 defeats; Mayweather, Jr and Manny Pacquiao agreed to Rounds boxed: 407 Days after Mayweather defeated Carlos 26 knockouts Baldomir in 2006, he agreed to face Hoya, World Title Fights: 19 Rounds boxed: face off for the fi rst time in the richest moving up to junior-middleweight (154 363 pounds) for the bout. Hoya got a guaranteed World Title Fights: match-up in boxing history. $23.3 million and Mayweather, the winner, 24 ET Magazine gives you a World Titles: was paid a minimum $10 million. The fi ght ringside view of the 12-round WBC Flyweight Title; generated a total of $136 million IBF Junior Featherweight Title; World Titles: slugfest that got going WBC Super Featherweight Title; WBC Lightweight Title; WBC Super Featherweight Title (1998-2002); this morning WBO Welterweight Title (2); WBC Lightweight Title (2002-2004); WBC Super Welterweight Title WBC Super Lightweight Title (2005-2006); IBF Welterweight Title (2006); WBC Welterweight Title (2006-2008, 2011-present); Awards and Recognition: ESPN Fighter of the Year (2006, 2008 & 2009) Mayweather vs Saul Alvarez (2013): WBC Super Welterweight Title (2007, 2013-present); 2.25 million WBA Super Welterweight Super World Title (2012-present); Ring Magazine Fighter of the Year (2006, 2008 & 2009) Billed as “The One”, it set a record for largest WBA Welterweight Unifi ed World Title (2014-present) Boxing Writers Association of America Fighter of the gate for a boxing match at $20 million with Year (2006, 2008 & 2009) the MGM Grand Arena selling out in a day. -

Continuing to Reform Professional Boxing Hearing Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate

S. HRG. 108–890 CONTINUING TO REFORM PROFESSIONAL BOXING HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION FEBRUARY 5, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 96–083 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:38 Mar 27, 2006 Jkt 096083 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\96083.TXT JACK PsN: JACKF SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CONRAD BURNS, Montana DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii TRENT LOTT, Mississippi JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota GORDON SMITH, Oregon RON WYDEN, Oregon PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BILL NELSON, Florida GEORGE ALLEN, Virginia MARIA CANTWELL, Washington JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JEANNE BUMPUS, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel KEVIN D. KAYES, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:38 Mar 27, 2006 Jkt 096083 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\96083.TXT JACK PsN: JACKF C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on February 5, 2003 ........................................................................ -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? AEW: All Out 2020 September 5th, 2020, 8:00 p.m. ET / 5:00 p.m. PT Don't miss the must-see event that started it all as All Elite Wrestling presents All Out: The most anticipated pro wrestling pay-per-view of the year! SD standard definition $49.99 HD high definition $49.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until November 13th, 2020 Ring Of Honor: The Very Best of Death Before Dishonor (Taped Premiere) September 25th, 2020, 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT Don’t miss this unprecedented, acclaimed collection featuring some of the greatest matches in pro wrestling history! Stars CM Punk, Bryan Danielson, Tyler Black, Samoa Joe, Briscoes, Rush, Claudio Castagnoli, Nigel McGuinness and many more in action, plus the Cage of Death! SD standard definition $14.99 HD high definition $14.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until December 18th, 2020 UFC 254: Khabib vs Gaethje October 24th, 2020, 2:00 p.m. -

Collins FACT SHEET for HIS SEPT

Keenan Collins FACT SHEET FOR HIS SEPT. 9 FIGHT IN PHILADELPHIA AGAINST Gabriel Rosado • 34 years old (Nov. 8th, 1976) •Born in Brooklyn, NY & moved to the York Pa when he was 5 and was a star basketball player when he got to High School and had a basketball scholarship to attend NC. Keenan went to jail in 1995 for aggravated assault and once he was released he moved to Reading at the age of 22 and started boxing at King’s Gym and compiled an amateur record of 22-5 with a win over hot prospect Mike Jones as an amateur. •13-6, 9 KOs; Just lost a 12rd. decision to World rated Charles Whittaker in the Cayman Islands but made it such a great fight that his ranking had gone up in the USBA to #13. •Turned pro in 2004 at age 26 but first went to a gym at age 22, although he started boxing just to get in shape for Semi Pro Basketball at the age of 22 he instantly fell in love with the sport. •Upcoming fight: September 9 vs. Gabriel Rosado (17-5 10 KOs) at Asylum Arena, 7 West Ritner Street (South Philadelphia). Tickets are priced at $45 and $65 and can be purchased by calling Peltz Boxing (215-765-0922) or going online at www.peltzboxing.com. College students can purchase tickets at the door for $15 with their student ID card. •Trainer: Marshall Kauffman of Reading Pa, who has been Keenan’s trainer along with Jason Kauffman as an amateur and pro: “Keenan’s has had some bumps in the road but he has the potential to really make a name for himself if he would just bring all of his tools to work with him on Sept. -

Polytechnic Tutoring Center

Polytechnic Tutoring Center Final Exam Review - CS 1114, Spring 2020 Disclaimer: This mock exam is only for practice. It was made by tutors in the Polytechnic Tutoring Center and is not representative of the actual exam given by the CS Department. 1 Given these assignments: a = 5, b = 2, c = 1.5 and s = ‘0.5’ write the type and value of the following expressions. Circle ERROR if the expression will result in a run time error. Statement: Type: Value: ERROR: float(a) / b ______ ______ ERROR s * b ______ ______ ERROR a / b ______ ______ ERROR a % b ______ ______ ERROR c // a ______ ______ ERROR s > b ______ ______ ERROR s[1] ______ ______ ERROR a // b ______ ______ ERROR s[0] = ‘1’ ______ ______ ERROR CS 1114 Exam 1 Review Page 1 2 Convert the following (00101)2 = (__________)10 (179)10 = (__________)2 (2076)10 = (__________)16 (B7D)16 = (__________)2 3 Given two lists, write a function to compute their intersection. Result should be a list of all the numbers appear in both input lists. The numbers in the result list can be in any order. Sample Output: >>> num1 = [1,2,2,1] >>> num2 = [2,2] >>> print(intersection(num1, num2)) >>> [2] >>> num1 = [4,9,5] >>> num2 = [9,4,9,8,4] >>> print(intersection(num1, num2)) >>> [9,4] # [4,9] is also a valid answer Code: def intersection(num1, num2): CS 1114 Exam 1 Review Page 2 4 Given two files boxers.csv (name,nickname,strength) and matchups.csv (name1,name2): boxers.csv matchups.csv James Douglas,“Buster”,84 Rocco Marciano,Jack Dempsey Cassius Clay,“Muhammad Ali”,99 Arnold Cream,Walker Smith Jr. -

A Fight Fan's First Fight

THOMAS HAUSER 113 It’s remarkable how many fight fans have never been to a pro fight. A Fight Fan’s First Fight From time to time, I’m asked why I like boxing. The best answer I can give is, go to a fight and see for yourself. Television covers the sport well, but there’s no substitute for live action. Better yet; go to a club fight so you can get close to the ring, feel the action, and see the emotions etched on the fighters’ faces. Lance Kolb is a longtime fight fan. One of his great-grandfathers was Giovanni Giuseppe Terranova, who was born in Italy and fought in the United States under the name “Red Cap Wilson” from 1912 through 1927. Lance’s own early life wasn’t a bed of roses. His first crib was a dresser drawer. Thereafter, in his words, “I was tossed back and forth between my parents and foster homes until my mother died from a combination of hepatitis B and drugs. Then I was adopted by a fabulous family and my life turned around.” Kolb, now forty-three, remembers sitting next to his grandfather on the sofa on Saturday and Sunday afternoons, watching fights on television. Sugar Ray Leonard, Marvin Hagler, and Ray Mancini turned him on to boxing. He graduated from Bridgewater State College and spent sixteen years in the military, rising from private to captain. “There were things I did when I was in the Army that were hard to do and I didn’t want to do,” he says.