Mps and Politics in Our Time John Healey MP, Mark Gill & Declan Mchugh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland

BRIEFING PAPER Number 4258, 19 June 2015 By Cheryl Pilbeam The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Historical background 3. The Wilson doctrine 4. Prison surveillance 5. Damian Green 6. The NSA files and metadata 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 4258, 19 June 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Historical background 4 3. The Wilson doctrine 5 3.1 Criticism of the Wilson doctrine 6 4. Prison surveillance 9 4.1 Alleged events at Woodhill prison 9 4.2 Recording of prisoner’s telephone calls – 2006-2012 10 5. Damian Green 12 6. The NSA files and metadata 13 6.1 Prism 13 6.2 Tempora and metadata 14 Legal challenges 14 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring 15 Cover page image copyright: Chamber-070 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped 3 The Wilson Doctrine Summary The convention that MPs’ communications should not be intercepted by police or security services is known as the ‘Wilson Doctrine’. It is named after the former Prime Minister Harold Wilson who established the rule in 1966. According to the Times on 18 November 1966, some MPs were concerned that the security services were tapping their telephones. In November 1966, in response to a number of parliamentary questions, Harold Wilson made a statement in the House of Commons saying that MPs phones would not be tapped. More recently, successive Interception of Communications Commissioners have recommended that the forty year convention which has banned the interception of MPs’ communications should be lifted, on the grounds that legislation governing interception has been introduced since 1966. -

View to Further Education in Wales

Wednesday Volume 496 15 July 2009 No. 112 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 15 July 2009 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2009 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; Tel: 0044 (0) 208876344; e-mail: [email protected] 271 15 JULY 2009 272 in Wales through the economic downturn, and that we House of Commons always put the Welsh economy on the road to recovery— unlike the last Conservative Government, who let tens Wednesday 15 July 2009 of thousands of young people become a generation of lost workers. We are being proactive in helping the economy to get through these difficult times, and that is The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock the truth. PRAYERS Lembit Öpik (Montgomeryshire) (LD): Is the Minister aware of the excellent work conducted by the support unit at the Department for Business, Innovation and [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] Skills, together with Lord Mandelson’s office? It helped to secure a very substantial loan from the Royal Bank BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS of Scotland so that a new manufacturing operation called Regal Fayre can be set up in the town of CONTINGENCIES FUND 2008-09 Montgomery. Will the Minister pass on my thanks, specifically to John Stewart in that department? Will he Ordered, also praise the Royal Bank of Scotland for living up to That there be laid before this House, Accounts of the Contingencies its requirement to support new business? Finally, may I, Fund, 2008-09 showing:– through the Minister, ask whether the Secretary of (1) a balance sheet; State for Wales will consider opening that new plant, (2) a cashflow statement; and which is a real success story and will lift the town of (3) notes to the account; together with the Report of the Montgomery out of recession? Comptroller and Auditor General thereon. -

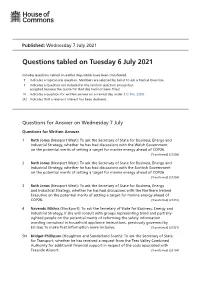

Questions Tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021

Published: Wednesday 7 July 2021 Questions tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 7 July Questions for Written Answer 1 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Welsh Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27308) 2 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Scottish Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27309) 3 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Northern Ireland Executive on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27310) 4 Navendu Mishra (Stockport): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, if she will consult with groups representing blind and partially- sighted people on the potential merits of reforming the safety information wording contained in household appliance instructions, previously governed by EU law, to make that information more inclusive. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

None of the Above: the UK House of Commons Votes on Reforming the House of Lords, February 2003

d:/1polq/74-3/mclean.3d ^ 24/6/3 ^ 16:6 ^ bp/sh None of the Above: The UK House of Commons Votes on Reforming the House of Lords, February 2003 IAIN MCLEAN, ARTHUR SPIRLING AND MEG RUSSELL The preamble to the UK's Parliament Act cent) of the members of a future house be 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c.13) states that that Act elected, but rejected the Royal Com- is a temporary measure only: mission's proposal that all appointed members be chosen by an independent Whereas it is intended to substitute for the House of Lords as it at present exists a Second appointments commission. Chamber constituted on a popular instead of This White Paper had a poor reception. hereditary basis, but substitution cannot be The Lord Chancellor's Department, immediately brought into operation . which issued it, later analysed the re- sponses to it. Of the 82 per cent of Attempts to bring the substitution into respondents who discussed election, operation in 1949 and 1968 failed. The 89 per cent `called for a house that was Labour Party's 1997 manifesto states: 50per cent or more elected'. Of the 17 per The House of Lords must be reformed. As an cent of respondents who discussed the initial, self-contained reform, not dependent future of the Church of England bishops, on further reform in the future, the right of 85 per cent opposed their continued pre- hereditary peers to sit and vote in the House sence in the house. Of the 12 per cent of of Lords will be ended by statute. -

Women Mps in Westminster Photographs Taken May 21St, June 3Rd, June 4Th, 2008

“The House of Commons Works of Art Collection documents significant moments in Parliamentary history. We are delighted to have added this unique photographic record of women MPs of today, to mark the 90th anniversary of women first being able to take their seats in this House” – Hugo Swire, Chairman, The Speaker's Advisory Committee on Works of Art. “The day the Carlton Club accepted women” – 90 years after women first got the vote aim to ensure that a more enduring image of On May 21st 2008 over half of all women women's participation in the political process Members of Parliament in Westminster survives. gathered party by party to have group photographs taken to mark the anniversary of Each party gave its permission for the 90 years since women first got the vote (in photographs to be taken. For the Labour February 1918 women over 30 were first Party, Barbara Follett MP, the then Deputy granted the vote). Minister for Women and Equality, and Barbara Keeley MP, who was Chair of the Labour Party Women’s Committee and The four new composite Caroline Adams, who works for the photographs taken party by Parliamentary Labour Party helped ensure that all but 12 of the Labour women party aim to ensure that a attended. more enduring image of For the Conservative women's participation in the Party, The Shadow Leader of the House of political process survives Commons and Shadow Minister for Until now the most often used photographic Women, Theresa May image of women MPs had been the so called MP and the Chairman “Blair Babes” picture taken on 7th May 1997 of the Conservative shortly after 101 Labour women were elected Party, Caroline to Westminster as a result of positive action by Spelman MP, enlisted the Labour Party. -

The Conservative Agenda for Constitutional Reform

UCL DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Constitution Unit Department of Political Science UniversityThe Constitution College London Unit 29–30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU phone: 020 7679 4977 fax: 020 7679 4978 The Conservative email: [email protected] www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit A genda for Constitutional The Constitution Unit at UCL is the UK’s foremost independent research body on constitutional change. It is part of the UCL School of Public Policy. THE CONSERVATIVE Robert Hazell founded the Constitution Unit in 1995 to do detailed research and planning on constitutional reform in the UK. The Unit has done work on every aspect AGENDA of the UK’s constitutional reform programme: devolution in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the English regions, reform of the House of Lords, electoral reform, R parliamentary reform, the new Supreme Court, the conduct of referendums, freedom eform Prof FOR CONSTITUTIONAL of information, the Human Rights Act. The Unit is the only body in the UK to cover the whole of the constitutional reform agenda. REFORM The Unit conducts academic research on current or future policy issues, often in collaboration with other universities and partners from overseas. We organise regular R programmes of seminars and conferences. We do consultancy work for government obert and other public bodies. We act as special advisers to government departments and H parliamentary committees. We work closely with government, parliament and the azell judiciary. All our work has a sharply practical focus, is concise and clearly written, timely and relevant to policy makers and practitioners. The Unit has always been multi disciplinary, with academic researchers drawn mainly from politics and law. -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

Hearing of Foreign Secretary Jack Straw Before the House of Commons on the Forthcoming IGC (10 September 2003)

Hearing of Foreign Secretary Jack Straw before the House of Commons on the forthcoming IGC (10 September 2003) Caption: On 10 September 2003, Jack Straw answers the questions of the House of Commons Select Committee on European Scrutiny. The Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs is heard on the subject of preparations for the IGC, the specific issues involved in the negotiations and the United Kingdom’s room for manoeuvre. Source: Select Committee on European Scrutiny, House of Commons, Examination of Witnesses – Rt Hon Jack Straw, Mr Kim Darroch and Mr Tom Drew, Minutes of Evidence, Questions 1-74, 10.09.03, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmselect/cmeuleg/1078/3091001.htm. Copyright: House of Lords - UK Parliament URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/hearing_of_foreign_secretary_jack_straw_before_the_house_of_commons_on_the_forthcoming _igc_10_september_2003-en-57a097fd-cd5d-431d-840a-0002187e45e5.html Publication date: 19/12/2013 1 / 17 19/12/2013 House of Commons – Select Committee on European Scrutiny, Minutes of evidence, Examination of Witnesses (Questions 1- 74) Wednesday 10 September 2003 – Rt Hon Jack Straw, Mr Kim Darroch and Mr Tom Drew Q1 Chairman: Foreign Secretary, welcome to the European Scrutiny Committee. I understand that you were thinking this was your first appearance in front of our Committee and, indeed, it is. It is the first time we have had the Foreign Secretary in front of our Committee. I am sure we are both looking forward to it. This particular meeting is to discuss the very important issue of the pending IGC on the Convention proposals. Could I kick off by asking the question, how much room for manoeuvre will there be at the IGC to make changes in the draft Treaty, given the pressure from many quarters to keep the text largely as it is? Mr Straw: I think there will be significant potential for manoeuvre.