Struggling with Scale: Ebola's Lessons for the Next Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angola Moose 100 Years

Serving the Steuben County 101 lakes area since 1857 Buck Lake Concert to benefi t woman Showers and Weather battling cancer storms early, mostly cloudy, Page A2 high 86. Low 70. Page A9 Angola, Indiana FRIDAY, AUGUST 22, 2014 kpcnews.com 75 cents GOOD Angola Moose 100 years old BY JENNIFER DECKER MORNING [email protected] ANGOLA — An Angola family Love’s to make fraternity has performed hundreds of good deeds and charitable acts donation to over the years. Make that 100 years’ Literacy Coalition worth in the city. ANGOLA — Oklahoma The Loyal Order of Moose, City, Oklahoma-based Angola Lodge No. 1568, 108 N. Love’s Travel Stops & Martha St., will mark its 100th Country Stores opened its year with a centennial celebration 12th Indiana location at Tuesday from noon to 10 p.m. at Interstate 69 and U.S. 20 the Angola Moose Family Center. Thursday. A special Moose ceremony will be At a Thursday, Sept. 4, held at 7 p.m. The celebration will ribbon cutting at 4 p.m., a highlight awareness of all which news release said Love’s will the Moose accomplish present a $2,000 donation to The Moose is an international the Steuben County Literacy family-fraternal organization Coalition. of men and women helping the The new Love’s travel community. It was founded in the stop features a Hardee’s 1800s with the goal of offering restaurant, gourmet coffee, men the chance to gather socially. travel items and gift Year round, the Moose stay merchandise. The new 24/7 busy with steak fries, barbecues location also offers 118 and other benefi ts to help funding truck parking spaces, seven assistance with children. -

Inside the Ebola Wars the New Yorker

4/13/2017 Inside the Ebola Wars The New Yorker A REPORTER AT LARGE OCTOBER 27, 2014 I﹙UE THE EBOLA WARS How genomics research can help contain the outbreak. By Richard Preston Pardis Sabeti and Stephen Gire in the Genomics Platform of the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They have been working to sequence Ebola’s genome and track its mutations. he most dangerous outbreak of an emerging infectious disease since the appearance of H.I.V., in the early nineteen-eighties, seems to have begun on DTecember 6, 2013, in the village of Meliandou, in Guinea, in West Africa, with the death of a two-year-old boy who was suffering from diarrhea and a fever. We now know that he was infected with Ebola virus. The virus is a parasite that lives, normally, in some as yet unidentified creature in the ecosystems of equatorial Africa. This creature is the natural host of Ebola; it could be a type of fruit bat, or some small animal that lives on the body of a bat—possibly a bloodsucking insect, a tick, or a mite. Before now, Ebola had caused a number of small, vicious outbreaks in central and eastern Africa. Doctors and other health workers were able to control the outbreaks quickly, and a belief developed in the medical and scientific communities that Ebola was not much of a threat. The virus is spread only through direct contact with blood and bodily fluids, and it didn’t seem to be mutating in any significant way. -

Eradicating Ebola: Lessons Learned and Medical Advancements Hearing

ERADICATING EBOLA: LESSONS LEARNED AND MEDICAL ADVANCEMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 4, 2019 Serial No. 116–44 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/, http://docs.house.gov, or http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–558PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York, Chairman BRAD SHERMAN, California MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Ranking GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York Member ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JOE WILSON, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TED S. YOHO, Florida DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois AMI BERA, California LEE ZELDIN, New York JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JIM SENSENBRENNER, Wisconsin DINA TITUS, Nevada ANN WAGNER, Missouri ADRIANO ESPAILLAT, New York BRIAN MAST, Florida TED LIEU, California FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida SUSAN WILD, Pennsylvania BRIAN FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania DEAN PHILLIPS, Minnesota JOHN CURTIS, Utah ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota KEN BUCK, Colorado COLIN ALLRED, Texas RON WRIGHT, Texas ANDY LEVIN, Michigan GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania ABIGAIL SPANBERGER, Virginia TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania GREG PENCE, Indiana -

Africa Update

ML Strategies Update David Leiter, [email protected] ML Strategies, LLC Georgette Spanjich, [email protected] 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Sarah Mamula, [email protected] Washington, DC 20004 USA 202 296 3622 202 434 7400 fax FOLLOW US ON TWITTER: @MLStrategies www.mlstrategies.com SEPTEMBER 18, 2014 Africa Update Leading the News West Africa Ebola Outbreak On September 10th, the United Nations (U.N.) World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the number of Ebola cases in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) had doubled over the past week to total 62 cases. Thirty-five of the patients infected with Ebola have died, including seven health care workers. The Ebola outbreak in the DRC is separate from the worsening Ebola crisis in West Africa. All of the cases in the DRC are localized in Jeera country and can all be traced to one initial case that was reported on August 26th. The new statistics for the Ebola outbreak in the DRC were posted here. On September 11th, Liberian Finance Minister Amara Konneh held a press conference on the impacts of the Ebola outbreak in Liberia, warning that the country is at war with an enemy that it cannot see. Minister Konneh’s remarks echo those delivered last week by Liberian Defense Minister Brownie Samukai, who cautioned that the Ebola crisis poses a serious threat to Liberia’s national existence. Both ministers reported that the epidemic has disrupted the country’s ability to function normally and put further strains on Liberia’s already weak health care infrastructure. Excerpts from both press conferences were highlighted here. -

Police Can't Find Items Sought for DNA Testing in 1980 Death

oelweindailyregister.com OELWEIN DAILY REGISTER FRIDAY, AuG. 2, 2019 — 5 TODAY IN HISTORY Police can’t find items sought Today is Friday, Aug. 2, the 214th day of 2019. There are 151 days left in the year. for DNA testing in 1980 death LOCAL HISTORY HIGHLIGHT By RYAN J. FOLEY prepared and he signed But officials with the Di- Beeman’s lawyers say that Associated Press at the end of a two-day vision of Criminal Investiga- if DNA from the sperm can IOWA CITY — Law en- interrogation. Prosecutors tion and Muscatine County be analyzed and is consistent forcement officials say they argued at trial that Beeman Sheriff’s Office said in court with another man’s profile, have lost track of evidence and Winkel randomly met filings last week that they that could prove their client from a 1980 murder case in Muscatine on April 21, have searched and cannot has been wrongly impris- that an Iowa inmate wants 1980. They allege he took find the evidence. They say oned for 39 years. They say to examine for DNA that her for a motorcycle ride retired investigators who Beeman’s claims of inno- could prove his innocence or to the park and raped and worked the case also have cence are bolstered by a lack confirm his guilt. killed her after she rejected no idea of its whereabouts. of evidence tying him to the William Beeman is his advances. Muscatine County Attorney scene and testimony that serving a life sentence in the Winkel had been kicked in Alan Ostergren has asked a put Beeman elsewhere and stabbing death of 22-year- the head, choked and stabbed judge to deny the request for Winkel with another man at old Michiel Winkel. -

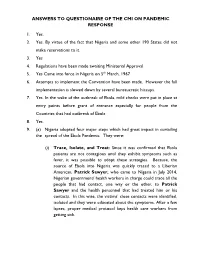

Nigeria MLA Replies to the Pandemic Response Questionnaire

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONAIRE OF THE CMI ON PANDEMIC RESPONSE 1. Yes. 2. Yes. By virtue of the fact that Nigeria and some other 190 States did not make reservations to it. 3. Yes 4. Regulations have been made awaiting Ministerial Approval 5. Yes Came into force in Nigeria on 5th March, 1967 6. Attempts to implement the Convention have been made. However the full implementation is slowed down by several bureaucratic hiccups. 7. Yes. In the wake of the outbreak of Ebola, mild checks were put in place at entry points before grant of entrance especially for people from the Countries that had outbreak of Ebola 8. Yes. 9. (a) Nigeria adopted four major steps which had great impact in curtailing the spread of the Ebola Pandemic. They were: (i) Trace, Isolate, and Treat: Since it was confirmed that Ebola patients are not contagious until they exhibit symptoms such as fever, it was possible to adopt these strategies. Because, the source of Ebola into Nigeria was quickly traced to a Liberian American, Patrick Sawyer, who came to Nigeria in July 2014, Nigerian government/ health workers in charge could trace all the people that had contact, one way or the other, to Patrick Sawyer and the health personnel that had treated him or his contacts. In this wise, the victims’ close contacts were identified, isolated and they were educated about the symptoms. After a few lapses, proper medical protocol kept health care workers from getting sick. (ii) Early Detection before many people could be exposed: It is generally believed that anyone with Ebola, typically, will infect about two more people, unless something is done to intervene. -

Annual Report 2019 New Museum Bedford /Artworks! Art a Special Thanks to the Following for Supplying Photos to NBAM for Use in the 2019 Annual Report

Annual Report 2019 New Bedford Art /ArtWorks! Bedford Museum New A special thanks to the following for supplying photos to NBAM for use in the 2019 annual report: Carly Costello Tobey DaSilva Vilot Foulk John Maciel Mark Medeiros Ashley Occhino Deb Smook Virginia Sutherland Jamie Uretsky Designed by Carly Costello www.carlycostellodesigns.com CONTENTS Letter From The Director 2 Exhibitions 4 Education & Outreach 6 Creative Courts 8 artMOBILE 10 Barr-Klarman Massachusetts Art Initiative 12 Feasibility Study 14 Experiences & Events 16 Media & Press 18 Year In Numbers 20 Donors 22 Staff 24 Letter From The Director Letter From The Director: REAFFIRMING OUR COMMITMENT TO THE COMMUNITY Dear Friend of the Museum, There are many ways to measure success. As this Annual Report shows, 2019 was a resoudingly successful year by many of them. With your help: • We exceeded our artMOBILE campaign goal, raising $50,000 to replace our oldest vehicle, a 1995 minivan that has clocked nearly 300,000 miles allowing this outreach program to continue. • Our outreach programs expanded further into the New Bedford and across the SouthCoast with initiatives driven by the Community Foundation of Southeastern Massachusett’s Creative Commonwealth with Get Out & Art and Creative Courts. • We concluded the second phase of our feasibility study with the campaign totaling more than $111,000 in incredibly generous contributions from friends of the Art Museum, Massachusetts Cultural Council, and the City of New Bedford’s Community Preservation Act. • We served more than 8,000 people in our galleries, it was our second-busiest year ever with 25% of our guests traveling from out-of-state and from as far away as Australia and Portugal. -

Hello, and Welcome to Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, NY

Hello, and welcome to Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, NY. Our museum features a wide variety of American art, including folk art, fine art, American Indian art, and photography. This fall, the Fenimore is fortunate to be showcasing the special exhibit, Pete Souza: Two Presidents, One Photographer. Pete Souza was the official White House photographer for two extremely influential presidents on opposite ends of the political spectrum: Republican Ronald Reagan, our 40th president from 1981 to 1989, and Democrat Barack Obama, our 44th president and first African American president, from 2009 to 2016. Souza had unprecedented access while photographing these two men, recording moments that were central not only to their own lives but to the history of the United States and even the entire world. In this program, we'll explore some of these photographs and dig deeper into the moments they capture. Before his life as a politician, Ronald Reagan was an actor in Hollywood, playing parts in many films in the 1940s and 1950s. He became more and more politically active, and in 1967 he was elected Governor of California as a Republican. He remained in this position until 1975 and the next year he made his first attempt to run for president but he would have to wait for the 1980 campaign for it to become a reality, defeating Jimmy Carter handily in the electoral vote, carrying 44 of the 50 states. Pete Souza became one of Reagan's official white house photographers in 1983, and soon afterwards he found himself recording the events after the deadliest attack against US Marines since world war two. -

Good Things on the Rise: the One-Sided Worldview of Hans Rosling

Good Things on the Rise: The One-Sided Worldview of Hans Rosling By Christian Berggren, Prof. emer. Industrial Management, Linköping University, Sweden, October 12, 2018 Charisma and positive messages about world development made Hans Rosling (1948– 2017), a former professor of international health at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, an international star. His posthumous gospel, Factfulness (1), which contains a collection of illustrative statistics and imaginative insights, has reached a global audience. In the United States, Bill Gates recently announced that he will hand out the book to all graduating university students, and 32 more translations are in the pipeline. An article in the science journal Nature praised the book in glowing terms: “This magnificent book ends with a plea for a factual world view. …Like his famous presentations, it throws down a gauntlet to doom-and-gloomers in global health by challenging preconceptions and misconceptions.” (2) However, Factfulness actually employs a biased selection of variables, avoids analysis of negative trends, and does not discuss any of the serious challenges related to continual population growth. A policy based on the simplistic worldview presented in Factfulness could have serious consequences. Who will dare stand up to media sensation Hans Rosling? This question asked by four writers in a leading Swedish daily in October 2015. Their criticism of his cavalier attitude toward the rapid rise in Africa’s population went unanswered. Perhaps the famous lecturer was leery of entering into a dialogue that might reveal the weaknesses of his analysis. Despite his position as a professor at the Karolinska Institute, Rosling’s research production was meager. -

Global and Local Health – Legacy of Hans Rosling

Seminar Global and Local Health – Legacy of Hans Rosling When: 26th October, 2017. 9.00 – 13.00. Where: Jacob Berzelius, Berzelius väg 3 Please register for the event here: https://sv.surveymonkey.com/r/PC3JR9Z In 2006, Hans Rosling presented his TED talk, which made him known internationally and changed the way we look at the world. However, long before that Hans Rosling had discovered a disease related to Cassava toxicity. It is an interesting story of a researcher who went to Mozambique to work as a health worker. Hans Rosling and his wife had traveled from Sweden to Mozambique. He had studied medicine and public health. In mid-1981, a disease appeared in the province of Nampula, north of Mozambique causing paralysis, with blurred vision and difficulty speaking. Soon over 1,000 cases were reported. The condition was called Konzo, which, in the Yaka language (spoken in a village of southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo) means “tied legs.” Cassava is the third most important food crop in the tropics, after rice and maize. Esteemed by smallholder farmers for its tolerance to drought and infertile soils, the crop is inherently eco-efficient, offering a reliable source of food and income. Half a billion people in Africa eat cassava every day, and this high-starch root is also an important staple in Latin America and the Caribbean. The seminar “Global and Local Health – Legacy of Hans Rosling will discuss the disease Konzo in the context of research carried out by Hans Rosling. The seminar is a collaboration between Swedish Agriculture University, Uppsala (SLU – Global) and Centre for global health, Karolinska Institutet. -

Responding to the Ebola Epidemic in West Africa: What Role Does Religion Play? Case Study

WFDD CASE STUDY RESPONDING TO THE EBOLA EPIDEMIC IN WEST AFRICA: WHAT ROLE DOES RELIGION PLAY? By Katherine Marshall THE 2014 EBOLA EPIDEMIC was a human and a medical drama that killed more than 11,000 people and, still more, devastated the communities concerned and set back the development of health systems. Its impact was concentrated on three poor, fragile West African countries, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, but the tremors reverberated throughout the world, gen- erating reactions of compassion and fear, spurring mobilization of vast hu- man and financial resources, and inspiring many reflections on the lessons that should be learned by the many actors concerned. Among the actors were many with religious affiliations, who played distinctive roles at various points and across different sectors. This case study is one of a series produced by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University and the World Faiths De- velopment Dialogue (WFDD), an NGO established in the World Bank and based today at Georgetown University. The goal is to generate relevant and demanding teaching materials that highlight ethical, cultural, and religious dimensions of contemporary international development topics. This case study highlights the complex institutional roles of religious actors and posi- tive and less positive aspects of their involvement, and, notably, how poorly prepared international organizations proved in engaging them in a systematic fashion. An earlier case study on Female Genital Cutting (FGC or FGM) focuses on the complex questions of how culture and religious beliefs influ- ence behaviors. This case was prepared under the leadership of Katherine Marshall and Crys- tal Corman. -

Resolution Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on the Establishment of the United Nations Population Award

Information note on the United Nations Population Award United Nations Population Award 2017 Edition United Nations Population Award The United Nations General Assembly established the United Nations Population Award in resolution 36/201 on 17 December 1981. The Award is presented annually to an individual or individuals, or to an institution or institutions, or to any combination thereof, for the most outstanding contribution to the awareness of population questions or to their solutions. The Committee for the United Nations Population Award selects the laureates of the Award. The Committee is composed of ten representatives of Members States of the United Nations (Antigua and Barbuda, Bangladesh, Benin, Islamic Republic of the Gambia, Ghana, Haiti, Islamic Republic of Iran, Israel, Poland and Paraguay) elected by the Economic and Social Council for a term of three years (2016-2018). Laureates of the 2017 Award 1. Individual (posthumous) Professor Hans Rosling was selected in recognition of his dedication and unwavering commitment to public health, population dynamics and the eradication of poverty in his multiple capacities as a physician, a researcher and a teacher, and for his remarkable contribution to a better understanding of international and global health through his numerous publications and initiatives. While serving as a Medical Officer in Northern Mozambique in the 1980s, Dr. Rosling’s investigations led to the discovery of an epidemic paralytic disease now known as Konzo, and spent two decades studying outbreaks of this disease in remote rural areas across Africa. As a champion of international cooperation, Dr. Rosling led health research collaborations with universities in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.