Downloaded From: Version: Accepted Version Publisher: Edinburgh University Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Machinations in Fleet Street: Roy Thomson, Cecil King, and the Creation of a Magazine Monopoly

Machinations in Fleet Street: Roy Thomson, Cecil King, and the creation of a magazine monopoly Howard Cox and Simon Mowatt ABH Annual Conference UCLAN 27-28 June 2013 Leading English Magazine Publishers Jan 1957 ODHAMS PRESS AMALGAMATED PRESS • Daily Herald • Daily Telegraph • The People • Woman’s Weekly • Woman • Woman’s Illustrated • Illustrated • Everybody’s • Southern Television HULTON PRESS • Picture Post GEORGE NEWNES • Woman’s Own • Tit-Bits Leading English Magazine Publishers Jan 1959 ODHAMS PRESS FLEETWAY PRESS • Daily Herald • Daily Mirror • The People • Sunday Pictorial • Woman • Woman’s Weekly • Woman’s Realm • Woman’s Illustrated • Illustrated • Everybody’s • Associated Television HULTON PRESS • Picture Post GEORGE NEWNES • Woman’s Own • Woman’s Day • Tit-Bits Leading English Magazine Publishers in Jan 1961 ODHAMS PRESS FLEETWAY PRESS • Daily Herald • Daily Mirror • The People • Sunday Pictorial • Woman • Woman’s Weekly • Woman’s Realm • Woman’s Illustrated • Woman’s Own • Everybody’s • Woman’s Day • Associated Television • Tit-Bits • Illustrated A Marriage of Convenience ODHAMS PRESS THOMSON NEWSPAPERS • Daily Herald • The Scotsman • The People • Sunday Times • Woman • Other newspapers, • Woman’s Realm mainly provincial • Woman’s Own • Scottish Television • Woman’s Day • Tit-Bits • Illustrated A Monopoly of Convenience ODHAMS PRESS FLEETWAY PRESS • Daily Herald • Daily Mirror • The People • Sunday Pictorial • Woman • Woman’s Weekly • Woman’s Realm • Woman’s Illustrated • Woman’s Own • Everybody’s • Woman’s Day • Over 100 -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

X-Men, Alpha Flight, and all related characters TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 0 8 THIS ISSUE: INTERNATIONAL THIS HEROES! ISSUE: INTERNATIONAL No.83 September 2015 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 featuring an exclusive interview with cover artists Steve Fastner and Rich Larson Alpha Flight • New X-Men • Global Guardians • Captain Canuck • JLI & more! Volume 1, Number 83 September 2015 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Steve Fastner and Rich Larson COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Martin Pasko Howard Bender Carl Potts Jonathan R. Brown Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: International X-Men . 2 Rebecca Busselle Samuel Savage The global evolution of Marvel’s mighty mutants ByrneRobotics.com Alex Saviuk Dewey Cassell Jason Shayer FLASHBACK: Exploding from the Pages of X-Men: Alpha Flight . 13 Chris Claremont Craig Shutt John Byrne’s not-quite-a team from the Great White North Mike Collins David Smith J. M. DeMatteis Steve Stiles BACKSTAGE PASS: The Captain and the Controversy . 24 Leopoldo Duranona Dan Tandarich How a moral panic in the UK jeopardized the 1976 launch of Captain Britain Scott Edelman Roy Thomas WHAT THE--?!: Spider-Man: The UK Adventures . 29 Raimon Fonseca Fred Van Lente Ramona Fradon Len Wein Even you Spidey know-it-alls may never have read these stories! Keith Giffen Jay Williams BACKSTAGE PASS: Origins of Marvel UK: Not Just Your Father’s Reprints. 37 Steve Goble Keith Williams Repurposing Marvel Comics classics for a new audience Grand Comics Database Dedicated with ART GALLERY: López Espí Marvel Art Gallery . -

Mass Circulation Periodicals and the Harmsworth Legacy in the British Popular Magazine Industry

Mass Circulation Periodicals and the Harmsworth Legacy in the British Popular Magazine Industry Howard Cox University of Worcester Paper prepared for the European Business History Association Annual Conference, Bergen, Norway, 21-23 August 2008. This is a working draft and should not be cited without first obtaining the consent of the author. Professor Howard Cox Worcester Business School University of Worcester Henwick Grove Worcester WR2 6AJ UK Tel: +44 (0)1905 855400 e-mail: [email protected] 1 Mass Circulation Periodicals and the Harmsworth Legacy in the British Popular Magazine Industry Howard Cox University of Worcester Introduction This paper reviews some of the main developments in Britain’s popular magazine industry between the early 1880s and the mid 1960s. The role of the main protagonists is outlined, including the firms developed by George Newnes, Arthur Pearson, Edward Hulton, William and Gomer Berry, William Odhams and Roy Thomson. Particular emphasis is given to the activities of three members of the Harmsworth dynasty, of whom it could be said played the leading role in developing the general character of the industry during this period. In 1890s Alfred Harmsworth and his brother Harold, later Lord Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere respectively, created a publishing empire which they consolidated in 1902 through the formation of the £1.3 million Amalgamated Press (Dilnot, 1925: 35). During the course of the first half of the twentieth century, Amalgamated Press held the position of Britain’s leading popular magazine publisher, although the company itself was sold by Harold Harmsworth in 1926 to the Berry brothers in order to help pay the death duties on Alfred Harmsworth’s estate. -

Monopoly, Power and Politics in Fleet Street: the Controversial Birth of IPC Magazines, 1958-63

Monopoly, Power and Politics in Fleet Street: The Controversial Birth of IPC Magazines, 1958-63 Howard Cox and Simon Mowatt Britain’s newspaper and magazine publishing business did not fare particularly well during the 1950s. With leading newspaper proprietors placing their desire for political influence above that of financial performance, and with working practices in Fleet Street becoming virtually ungovernable, it was little surprise to find many leading periodical publishers on the verge of bankruptcy by the decade’s end. A notable exception to this general picture of financial mismanagement was provided by the chain of enterprises controlled by Roy Thomson. Having first established a base in Scotland in 1953 through the acquisition of the Scotsman newspaper publishing group, the Canadian entrepreneur brought a new commercial attitude and business strategy to bear on Britain’s periodical publishing industry. Using profits generated by a string of successful media activities, in 1959 Thomson bought a place in Fleet Street through the acquisition of Lord Kemsley’s chain of newspapers, which included the prestigious Sunday Times. Early in 1961 Thomson came to an agreement with Christopher Chancellor, the recently appointed chief executive of Odhams Press, to merge their two publishing groups and thereby create a major new force in the British newspaper and magazine publishing industry. The deal was never consummated however. Within days of publicly announcing the merger, Odhams found its shareholders being seduced by an improved offer from Cecil King, Chairman of Daily Mirror Newspapers, Ltd., which they duly accepted. The Mirror’s acquisition of Odhams was deeply controversial, mainly because it brought under common ownership the two left-leaning British popular newspapers, the Mirror and the Herald. -

The Beano and the Dandy: Discover a Long Lost Hoard of Vintage Comic Gold

FREE THE BEANO AND THE DANDY: DISCOVER A LONG LOST HOARD OF VINTAGE COMIC GOLD... PDF DC Thomson | 144 pages | 01 Aug 2016 | D.C.Thomson & Co Ltd | 9781845356040 | English | Dundee, United Kingdom Mother Nature's Cottage | Comics, Creepy comics, Comic covers The comic first appeared on 30 July[1] and was published weekly. In SeptemberThe Beano and the Dandy: Discover a Long Lost Hoard of Vintage Comic Gold. Beano' s 3,th issue was published. Each issue is published on a Wednesday, with the issue date being that of the following Saturday. The Beano reached its 4,th issue on 28 August The style of Beano humour has shifted noticeably over the years, [4] though the longstanding tradition of anarchic humour has remained. Historically, many protagonists were characterised by their immoral behaviour, e. Although the readers' sympathies are assumed to be with the miscreants, the latter are very often shown punished for their actions. Recent years have seen a rise in humour involving gross bodily functions, especially flatulence which would have been taboo in children's comics prior to the swhile depictions of corporal punishment have declined. For example, the literal slipper — the most common form of chastisement for characters such as Dennis, Minnie the Minx and Roger the Dodger — has become the name of the local chief of police Sergeant Slipper. InD. Thomson had first entered the field of boys' story papers with Adventure. Although The Vanguard folded inthe others were a great triumph and became known as "The Big Five"; they ended Amalgamated Press's near-monopoly of the British comic industry. -

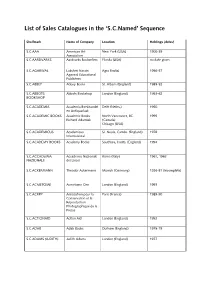

List of Sales Catalogues in the 'S.C.Named' Sequence

List of Sales Catalogues in the ‘S.C.Named’ Sequence Shelfmark Name of Company Location Holdings (dates) S.C.AAA American Art New York (USA) 1900-39 Association S.C.AARDVARKS Aardvarks Booksellers Florida (USA) no date given S.C.AGARWAL Lakshmi Narain Agra (India) 1956-57 Agarwal Educational Publishers S.C.ABBEY Abbey Books St. Albans (England) 1989-92 S.C.ABBOTS Abbots Bookshop London (England) 1953-62 BOOKSHOP S.C.ACADEMIA Academia Boekhandel Delft (Neths.) 1950 en Antiquariaat S.C.ACADEMIC BOOKS Academic Books North Vancouver, BC 1995 Richard Adamiak (Canada) Chicago (USA) S.C.ACADEMICUS Academicus St. Neots, Cambs. (England) 1978 International S.C.ACADEMY BOOKS Academy Books Southsea, Hants. (England) 1994 S.C.ACCADEMIA Accademia Nazionale Rome (Italy) 1961, 1963 NAZIONALE dei Lincei S.C.ACKERMANN Theodor Ackermann Munich (Germany) 1926-81 (incomplete) S.C.ACMETOME Acmetome One London (England) 1993 S.C.ACRPP Association pour la Paris (France) 1989-90 Conservation et la Réproduction Photographique de la Presse S.C.ACTIONAID Action Aid London (England) 1992 S.C.ADAB Adab Books Durham (England) 1975-79 S.C.ADAMS (JUDITH) Judith Adams London (England) 1977 S.C.ADDISON Reginald Addison London (England) no date given S.C.ADDISON WESLEY Addison Wesley Reading, Mass. (USA) 1961, 1962, 1964 Publishing Company S.C.ADER Etienne Ader Paris (France) 1933-67 (incomplete) Ader Picard Tajan 1981-91 S.C.ADLER Arno Adler Lubeck (Germany) no date given S.C.AEGIS Aegis Buch- und (Germany) 1959, 1962, 1964-65 Kunstantiquariat S.C.AEROPHILIA Aerophlia -

Look and Learn a History of the Classic Children's Magazine By

Look and Learn A History of the Classic Children's Magazine By Steve Holland Text © Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 2006 First published 2006 in PDF form on www.lookandlearn.com by Look and Learn Magazine Ltd 54 Upper Montagu Street, London W1H 1SL 1 Acknowledgments Compiling the history of Look and Learn would have be an impossible task had it not been for the considerable help and assistance of many people, some directly involved in the magazine itself, some lifetime fans of the magazine and its creators. I am extremely grateful to them all for allowing me to draw on their memories to piece together the complex and entertaining story of the various papers covered in this book. First and foremost I must thank the former staff members of Look and Learn and Fleetway Publications (later IPC Magazines) for making themselves available for long and often rambling interviews, including Bob Bartholomew, Keith Chapman, Doug Church, Philip Gorton, Sue Lamb, Stan Macdonald, Leonard Matthews, Roy MacAdorey, Maggie Meade-King, John Melhuish, Mike Moorcock, Gil Page, Colin Parker, Jack Parker, Frank S. Pepper, Noreen Pleavin, John Sanders and Jim Storrie. My thanks also to Oliver Frey, Wilf Hardy, Wendy Meadway, Roger Payne and Clive Uptton, for detailing their artistic exploits on the magazine. Jenny Marlowe, Ronan Morgan, June Vincent and Beryl Vuolo also deserve thanks for their help filling in details that would otherwise have escaped me. David Abbott and Paul Philips, both of IPC Media, Susan Gardner of the Guild of Aviation Artists and Morva White of The Bible Society were all helpful in locating information and contacts. -

465 Chapter Nineteen Woman Appeal. a New Rhetoric of Consumption: Women's Domestic Magazines in the 1920S and 1930S Fiona Hack

Chapter Nineteen Woman Appeal. A New Rhetoric of Consumption: Women’s Domestic Magazines in the 1920s and 1930s Fiona Hackney When in 1926 two brothers from South Wales, William and Gomer Berry, struck a deal to acquire the entire business of the Amalgamated Press (AP), they took on the mantle of ‘Britain’s leading magazine publishing business,’ after the untimely death of AP owner and press magnate, Alfred Harmsworth (Lord Northcliffe) (Cox and Mowatt 2014: 60–3). The continued importance of magazines aimed at the female reader for the Berry’s empire was emphasised by William in his first speech as chairman, and in the coming years a host of new titles including Woman and Home, Woman’s Journal, Woman’s Companion, Wife and Home, Woman and Beauty and Home Journal were added to established staples such as Home Chat, Women’s Pictorial, Woman’s World and Woman’s Weekly. The launch of over fifty titles by AP and its rivals Newnes and Pearson, and Odhams Press, put women and their magazines at the forefront of popular publishing in the interwar years. By the end of the 1930s Odhams Press, under the direction of its dynamic managing director Julias Elias (Lord Southwood), had usurped the AP’s position with its innovative publication Woman, which brought the visual appeal of good quality colour printing to a tuppeny weekly, something that previously had only been available in expensive, high-class magazines. The interwar years witnessed expansion and consolidation, struggle and innovation as these publishing giants competed to command the lucrative market for women’s magazines. -

Odhams (Watford) Ltd (1935-1983)

ODHAMS (WATFORD) LTD (1935-1983) Odhams (Watford) Ltd. was a pioneering printing company, established in 1935, situated in North Watford on the site where ASDA is currently located. When building started there in 1935, the area was mainly fields, and the coming of Odhams transformed not only the site, but also the neighbourhood, as houses, shops and schools were built to serve the expanding workforce.1 Little more than 20 years after arriving in Watford, Odhams was described as “one of the largest and most modern photogravure factories in the world, standing as it does on a 17½ acre site and employing nearly 2,500 work people”.2 It was established primarily to undertake high-speed colour photogravure printing of magazines, but it also had letterpress machines, which printed trade publications, magazines, catalogues, and books, published by its parent company, Odhams Press, as well as other publishers.3 Odhams (Watford) Ltd. was a subsidiary company of Odhams Press Ltd., and its story must begin with that of its parent company. ODHAMS PRIOR TO 1935 The founder of Odhams was William Odhams, who was born about 1812 in Sherborne, Dorset. He came to London in his 20s and worked as a compositor at the ‘Morning Post’. He started up in business about 1847, initially in partnership with a fellow compositor at the ‘Morning Post’, William Biggar.4 In 1847, the business obtained the contract for printing the ‘Guardian’, an ecclesiastical paper, which it held for over 75 years.5 The printing premises were originally at Beaufort Buildings, Savoy, and then moved to Burleigh Street.6 Other papers printed at Burleigh Street were the ‘Railway Times’, the ‘Investors’ Guardian’, and the ‘County Council Times’.7 In 1892, William Odhams sold the business, ‘William Odhams’, to his sons, William James Baird Odhams, and John Lynch Odhams. -

The Joseph M. Bruccoli Great War Collection at the Unversity of South Carolina: an Illustrated Catalog Elizabeth Sudduth [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Rare Books & Special Collections Publications Collections 2005 The Joseph M. Bruccoli Great War Collection at the Unversity of South Carolina: An Illustrated Catalog Elizabeth Sudduth [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/rbsc_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Sudduth, Elizabeth, ed. The Joseph M. Bruccoli Great War Collection at the Unversity of South Carolina: An Illustrated Catalog. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2005. http://www.sc.edu/uscpress/books/2005/3590.html © 2005 by University of South Carolina Used with permission of the University of South Carolina Press. This Book is brought to you by the Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rare Books & Special Collections Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOSEPH M. BRUCCOLI GREAT WAR COLLECTION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Joseph M. Bruccoli in France, 1918 Joseph M. Bruccoli JMB great war collection University of South Carolina THE JOSEPH M. BRUCCOLI GREAT WAR COLLECTION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA AN ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE Compiled by Elizabeth Sudduth Introduction by Matthew J. Bruccoli Published in Cooperation with the Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS © 2005 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Joseph M. -

Periodicals: Post 1850

PERIODICALS: POST 1850 ACE MALLOY, no. 62. London: Arnold book company, [n.d.] [1954?], 25.5 x 17.6 cm.Opie JJ 1 ACTION, 4th Dec. 1976. [2 copies] London: I.P.C. magazines, ltd., 27.9 x 22.7 cm. Opie JJ 2 ACTION COMICS [new series], no. 10: The lone avenger. Sydney: Action comics pty, 25.8 x 17.9 cm. Opie JJ 3 ADVENTURE, no. 18, 14th Jan. 1922; no. 1415, 1st Mar. 1952; no. 1549, 25th Sept. 1954; nos. 1598-99, 3rd-10th Sept. 1955; no. 1653, 22nd Sept. 1956; no. 1772, 3rd Jan. 1959; no. 1804, 15th Aug. 1959. London: D.C. Thomson & co., [dimensions vary]. Incorporated into ROVER, Jan. 1961 and retitled ROVER AND ADVENTURE. Opie JJ 4 Added entry ADVENTURE see also ROVER AND ADVENTURE. Added entry ADVENTURE INTO FEAR see FEAR. ADVENTURES INTO THE UNKNOWN, no. 116, April-May, 1960. New York: American comics group, 25.9 x 17.4 cm. Opie JJ 5 Added entry The ADVISER: a book for young people, nos. 1-3, Jan.-Mar. 1866; nos. 5-9. May - Sept. 1866; no. 11. Nov. 1866; nos. 8-11. Aug. - Nov. l868; nos. 1-3. Jan. - Mar. 1872; nos. 5-12. May - Dec. 1872. Glasgow: Scottish temperance league, 19.4 x 15.3 cm. (Bound with The BAND OF HOPE TREASURY) Opie JJ 835 (2) Added entry AGNEW, Stephen H. Silver spurs see The NEW BLACK BESS, no. 1: Silver spurs; or, The secret of the veiled princess. See also The NUGGET LIBRARY and DICK TURPIN LIBRARY, no. 125. -

Television-Annual-19

THE `T LIal_tVIgLio B ANNUAL FOR 1961 Every Viewer's Companion, with Souvenir Pictures of BBC and ITV Programmes and Personalities Edited by KENNETH BAILY ODHAMS PRESS LIMITED, LONG ACRE, LONDON CONTENTS EDITOR'S REVIEW:The Many-sided Vision page 7 FONTEYN COMES TO TELEVISION 26 LET ME PRAISE TEENAGERSwrites ALFIE BASS 28 ARE THERE TOO MANY TV DETECTIVES?asks RAYMOND FRANCIS 34 IN LEEDS I SOUGHT EXCITEMENTsays MARION RYAN 41 HOW THEY PUT THE SPORT INTO SATURDAY'S GRAND- STAND 46 I MIX STAGE AND TVsays DICKIE HENDERSON 51 ROBERT HORTONreports on Ridin' Along With Flint 55 PLAYS AND PLAYERSRemain the Best -loved TV Programmes 59 DAME EDITH SITWELL:a TV Enigma 71 MUSIC IN TELEVISION 74 TV FAME WAS TOO SOON FOR MEsays ROY CASTLE 77 THEY ARE WILY TV HOODWINKERS:The Effects Men 82 THEY DON'T KNOW MY NAMEan unexpected confession by BILLIE WHITELAW 87 REPORT ON YOUR FAVOURITE PROBATION OFFICER 93 JAZZ IS VISUAL-SoLet's HaveItOn TV says JOHNNY DANK WORTH 97 4 THE TELEVISION ANNUAL FOR 1961 Oneof the studio moments the riewer does not see. Variety' artistes waiting to do a "puppet" routine "stand-by" while cameramen, (glimpsedtopandright)"take" another act. 2 THE ADVENTURE OF NEWS ON TELEVISION by HUW THOMAS 100 WORK AND MARRIAGE MAKE A COSY FITforTEDDY JOHNSON andPEARL CARR 108 AN AGE OF KINGS 114 DAVID ATTENBOROUGH :A Profile 116 YANA SINGS 122 VARIETY TRIES TO BE THE SPICE OF TV 124 TELEVISION IS A WATCHDOG says JOHN FREEMAN 129 FOUR FEATHER FALLS:Western in Miniature 134 WITH RUPERT DAVIES IN THE WORLD OF MAIGRET 136 THE TEENAGE CULT: AProblem for TV 142 ALAN WHICKER: ADiagnosis of To -Night's Pertinent Reporter 145 V.I.P.s LIKE TOUGH INTERVIEWING says ROBIN DAY 150 IT'S TEAM WORK:"Emergency - Ward 10" 153 TV WATCHES THE WORLD:But Is it ImportantAsks ELAINE GRAND 156 YOUR FRIENDS THE STARS Bernard orchard page 39 Ken Dodd page 113 krthurI lanes 40 Sidne) James 121 Rosalie Crutchley 73 AlmaCogan 141 Russ Conway 76 Arthur Howard 144 Adrienne Corrie 81 Angela Bracewell 149 Kenneth Kendall 92 I.)fe Robertson 152 5 THAT OLD-TIME TELEVISION "This is the camera .