The Jewish Labor Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

Hyman Weintraub and William Goldberg Collection of Socialist Party Material, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt92902225 No online items Hyman Weintraub and William Goldberg Collection of Socialist Party Material, ca. 1924-1946 Processed by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Hyman Weintraub and William 831 1 Goldberg Collection of Socialist Party Material, ca. 1924-1946 Descriptive Summary Title: Hyman Weintraub and William Goldberg Collection of Socialist Party Material, Date (inclusive): ca. 1924-1946 Collection number: 831 Creator: Weintraub, Hyman Extent: 26 boxes (13 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Provenance/Source of Acquisition Collection was originally assembled by Hyman Weintraub and William Goldberg. -

"The Crisis in the Communist Party," by James Casey

THE CRISIS in the..; COMMUNIST PARTY By James Casey Price IDc THREE ARROWS PRESS 21 East 17th Street New York City CHAPTER I THE PEOPlES FRONT AND MEl'tIBERSHIP The Communist Party has always prided itself on its «line." It has always boasted of being a "revolutionary work-class party with a Marxist Leninist line." Its members have been taught to believe that the party cannot be wrong at any time on any question. Nonetheless, today this Communist Party line has thrown the member ship of the Communist Party into a Niagara of Confusion. There are old members who insist that the line or program has not been changed. There are new members who assert just as emphatically that the line certainly has been changed and it is precisely because of this change that they have joined the party. Hence there is a clash of opinion which is steadily mov ing to the boiling point. Assuredly the newer members are correct in the first part of their contention that the basic program of the Communist Party has been changed. They are wrong when they hold that this change has been for the better. Today the Communist Party presents and seeks to carry out the "line" of a People's Front organization. And with its slogan of a People's Front, it has wiped out with one fell swoop, both in theory and in practice, the fundamental teachings of Karl Marx and Freidrick Engels. It, too, disowns in no lesser degree in deeds, if not yet in words, all the preachings and hopes of Nicolai Lenin, great interpretor of Marx and founder of the U. -

The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 11:01 Labour Journal of Canadian Labour Studies Le Travail Revue d’Études Ouvrières Canadiennes The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A. Zumoff Volume 85, printemps 2020 Résumé de l'article Dans les premières années de la Grande Dépression, le Parti socialiste URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070907ar américain a attiré des jeunes et des intellectuels de gauche en même temps DOI : https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0006 qu’il était confronté au défi de se distinguer du Parti démocrate de Franklin D. Roosevelt. En 1936, alors que sa direction historique de droite (la «vieille Aller au sommaire du numéro garde») quittait le Parti socialiste américain et que bon nombre des membres les plus à gauche du Parti socialiste américain avaient décampé, le parti a perdu de sa vigueur. Cet article examine les luttes internes au sein du Partie Éditeur(s) socialiste américain entre la vieille garde et les groupements «militants» de gauche et analyse la réaction des groupes à gauche du Parti socialiste Canadian Committee on Labour History américain, en particulier le Parti communiste pro-Moscou et les partisans de Trotsky et Boukharine qui ont été organisés en deux petits groupes, le Parti ISSN communiste (opposition) et le Parti des travailleurs. 0700-3862 (imprimé) 1911-4842 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Zumoff, J. (2020). The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935. Labour / Le Travail, 85, 165–198. -

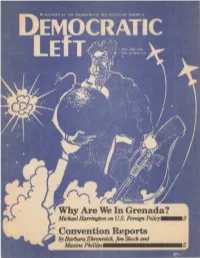

Why Are We in Grenada? Michael Harrington on U.S

Why Are We In Grenada? Michael Harrington on U.S. Foreign Policy - Convention Reports by Barbara Ehrenreich, Jim Shoch and Maxine PhilliPs STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT, AND ClRCULATION Sale! (Act of Aul!Usl 12. 1970: Sectinn 3611.'i. Title 39. Unitdl Slalt'' Code) l. TnleofPublica1n1-0EMOCRATICLEFT 2. Dale ofFihnir. November 29. 1983 3. Frcqut>1wv of lssU<.. Monthlv, except Jul)·. Aui..'Usl and Sale! Ocl'lber 4. [.ocaL10n of lmu\\n nffkt' of pubficatKm: ll.'i.1 Broadway. Room 801. New York -.. Y 1000.'l. 5. Location of Lilt.> ht.-adquarters or l?l'ot'ral busiot'M of fices nf th<! Publisht-r 115.1 Broadwav. Room Ml. Nl'W Sale! York. N. Y Hl003. 6. Name• and addrl'sM's of Publishers. Editor and Man ~l(l n !( Editor: Dcmocratit' Socialists of Am.,rica. Mi.:hae-1 Harrington. Maxin.- Phillips. all of 8.5.1 Broadwa~·. Ne"' / KRAZY KARL'S RED HOT LIT SALE! York. N Y 10003. 7. Owner; O..mo<Tat1<· Soc 1~l i sts of Am1•nca. l\S.1 Rrnad wav, New Yolii. N Y. 10003. ~~- I 8. Known bundholck·rs. mortJ,!ffi;!e<'S. and other ......'tint)' Don't miss these holiday bargains! Krazy Karl has to make room for holder. nwnmg or holdm)! l J>l'rrent or mor<' of IOlaJ amount• •fhondo; mort)?a)?t'S or ntht'r St'('UJ1tit-s: :"<lflt'. 1984 inventory. Prices have been slashed. Stock up now. 9. The purpnst'. function and nonprofit slat"" ulf~hi, 11r i:armatii111 and tilt- <'Xt'mpt status lur Ft-dt'ral lllrnfllt' tax purposes ha\" lll>t <·han1tt'd durini: prt'C<"<linl? l'.? month~ . -

A Symposium from SWEDEN to SOCIALISM

A Symposium Hobert Heilbroner FROM SWEDEN TO SOCIALISM A Small Symposium on Big Questions have recently posed a question to which I quire an extensive change—I will not say have no answer, but which seems to me to go "fall" —in its living standards. Wasteful private to the heart of the outlook for democratic consumption would have to yield to economical socialism, at least in the advanced capitalist public consumption, automobiles making way countries. The question is: how far beyond the for busses and trains, washing machines for borders of what I call "real but slightly Laundromats. How can a population that clearly imaginary Sweden" would we have to go enjoys its wasteful standard way of life be per- before a visitor to that land knew that he or she suaded to make such a change? was in a socialist, not a capitalist, country? 4. Bourgeois life itself may be a matter of Let me suggest some of the more obvious concern. Sweden is a highly pragmatic, comfort- answers—and the problems they raise: minded, nonideological place. Is that a culture 1. A small number of large corporations that socialism would seek? What other? constitute the dynamic core of the Swedish There are no doubt many ways in which economy. Would these corporations have to Sweden would have to change before the go? With what would they be replaced? The imaginary land to which we refer was unmis- one thing we know is that they should not be takably socialist. To indicate those ways, and nationalized. Then how governed? Or if to consider their economic and political costs, dismantled, into what sorts of units, themselves seems to me the manner in which democratic how governed? socialists should measure the challenge of the 2. -

Interracial Unionism in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and the Development of Black Labor Organizations, 1933-1940

THEY SAW THEMSELVES AS WORKERS: INTERRACIAL UNIONISM IN THE INTERNATIONAL LADIES’ GARMENT WORKERS’ UNION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF BLACK LABOR ORGANIZATIONS, 1933-1940 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Julia J. Oestreich August, 2011 Doctoral Advisory Committee Members: Bettye Collier-Thomas, Committee Chair, Department of History Kenneth Kusmer, Department of History Michael Alexander, Department of Religious Studies, University of California, Riverside Annelise Orleck, Department of History, Dartmouth College ABSTRACT “They Saw Themselves as Workers” explores the development of black membership in the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) in the wake of the “Uprising of the 30,000” garment strike of 1933-34, as well as the establishment of independent black labor or labor-related organizations during the mid-late 1930s. The locus for the growth of black ILGWU membership was Harlem, where there were branches of Local 22, one of the largest and the most diverse ILGWU local. Harlem was also where the Negro Labor Committee (NLC) was established by Frank Crosswaith, a leading black socialist and ILGWU organizer. I provide some background, but concentrate on the aftermath of the marked increase in black membership in the ILGWU during the 1933-34 garment uprising and end in 1940, when blacks confirmed their support of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and when the labor-oriented National Negro Congress (NNC) was irrevocably split by struggles over communist influence. By that time, the NLC was also struggling, due to both a lack of support from trade unions and friendly organizations, as well as the fact that the Committee was constrained by the political views and personal grudges of its founder. -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2010 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Title: Albert Glotzer papers Date (inclusive): 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes(27.7 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1991. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Albert Glotzer papers, [Box no., Folder no. -

The Socialist Party Convention

THE SOCIALIST PARTY CONVENTION By GENE . DENNIS Social Legislation in Massachusetts P. FRANKFELD The Schools and the People's Front RICHARD FRANK Farm Problems and Legislation ROBERT CLAY Steel Workers on the March B. K. GEBERT The Railway Labor Act JACK JOHNSTONE Youth in Industry D. DORAN Tv\'ENTY CENTS SPECIAL OFFER A free copy of Earl Browder's WHAT IS COMMUNISM? cloth edition, list price $2.00, will be given with every subscription to one of the following periodicals: The Communist A monthly magazine issued by the Communist Party of the U.S.A., dealing with the most vital social, economic and political issues of the day. Single copies 20 cents. ~ubscription $2.00 The Communist International Monthly publication of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, containing articles by outstanding leaders of the world Communist Parties. ;ingle copies 15 cents. Subscription $1.75. International Press Correspondence (Inprecorr) A weekly review of political events on the international arena. Single copies 10 cents. Subcription $5.00 Special Combinatirm Offer A subscription to all three of these important publications for one year may be had for the special price of $ 7. 2 0 Send your subscription to WORKERS LIBRARY PUBLISHERS P. 0. Box 148, Sta. D New York City NEW MASSES 31 East 27th S.reet New York, N. Y. I enclose $1 for which please send me the 15-week offer. Name------------------------------------------------------------ Address __________ ------------------------------------------- City_____________ _ _______________ State _________________ _ Occupation _________________ ----------------------- (c) DARN TOOTJN•..... WE•RE DIFFERENT You don't usually find the coupon right up here at the top. -

Exclusive Story of SP Convention Shows Collapse: Party Disintegrating and in Complete Control of Communists, Milwaukee

Exclusive Story of SP Convention Shows Collapse: Party Disintegrating and in Complete Control of Communists, Milwaukee Delegate Writes [events of March 26-29, 1937] by Frederic Heath Published in The New Leader [New York], vol. 20, no. 14 (April 3, 1937), pp. 1-2. The author of this story was a Wisconsin delegate to the national con- vention of the Norman Thomas-led Socialist Party. Held behind closed doors, this is the only uncensored story that has come out of the conven- tion. Fred Heath belongs to the generation of Victor L. Berger, Eugene V. Debs, Morris Hillquit, and other democratic Socialists and was one of the founders of the Socialist Party now captured by the Communists. • • • • • CHICAGO, Ill., March 26 [1937].1— It has fallen to Wisconsin Socialists to sit in a Socialist national convention and find themselves the only remnants of the once powerful American Socialist Party, sur- rounded by leering, victorious Communists who have made a com- plete capture of the movement we have given much of our lives to help build up. We had to take it here in Chicago today, for here was a national Socialist convention completely in the control of the enemy, a miracle that had been made possible by the arch betrayer, Norman Thomas. 1 This article seems to have been written in two parts and posted from Chicago to New York for publication following conclusion of the convention. 1 I am writing to The New Leader as, unfortunately, we of Wiscon- sin have no medium that we can freely use to enlighten each other on inner party matters. -

Labor and Migration; an Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION City Univ

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 044 500 VT 011 779 AUTHOR Brooks, Thomas R. TITLE Labor and Migration; An Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION City Univ. of New York, Brooklyn, N.Y. Brooklyn Coll. PUB DATE Feb 70 NOTE 40p. AVAILABLE FROM Director, Center for Migration Studies, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, New York 11210 ($5.00) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$2.10 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Employment Opportunities, *Immigrants, *Labor Economics, *Labor Unions, *Manpower Utilization, Migration ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography is intended to contribute toward an understanding of labor and migration, both of which have helped to shape our nation. A total of 131 works, including a few periodicals and newspapers, focus on immigration and internal migration as it affects organized and unorganized labor. (BH) I OfloANIVIMCG mtatII tbutikKY4 stS111,11/ °Ma lOvtistr04 04I 100.VES IS SUN 411.0tx.K40 IICIS 0/(5 Nit ofC t1 ettso. pa okzonvi011 ce,IviANG it100 % et* poos.co.,s voter DO rot %:(15 S"I'ttiVt Mrt.lt est,c1 Of :SerC CI CVO, Ito.4"0464118911 6M*FOR ) BROOKLYN, NEW YORK Halo Co Lt1 4. PREFACE -41 O "The stranger" has always presented problems and encountered problems. The biblical uJ injunction on the treatment of strangers is an early instance in our lvdeo-Christian heritage of an attempt to improve attitudes and actions toward the stranger. We in the United States must be sensitive to the presence of strangers. We are, as has been said many times, "a nation of immigrants." Even the Indians found by the first Europeans had only been here some 25 or 30,000 years, newcomers in a geological time sense. -

The Many Worlds of American Communism

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2019 The Many Worlds Of American Communism Joshua James Morris Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Morris, Joshua James, "The Many Worlds Of American Communism" (2019). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2178. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2178 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE MANY WORLDS OF AMERICAN COMMUNISM by JOSHUA JAMES MORRIS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 MAJOR: HISTORY (American) Approved By: _________________________________________ Advisor Date _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY JOSHUA JAMES MORRIS 2019 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have so many to thank for this project, starting with my mom and my dad for always believing in me. I also want to thank my committee, Elizabeth Faue, Fran Shor, Aaron Retish, Vicki Ruiz, and Louis Jones, without which I would not have been able to fully develop my research. My inspiration to continue studies in history I owe to Harold Marcuse and John Lloyd; they always made history something to embrace as both a passion and a challenge. I want to give a special thanks to Ronald Aronson for helping me with some of my research here in Detroit. I also want to give a tremendous thank you to all those whom I interviewed and took part in this project: Armando Ramirez, Beatrice Lumpkin, Danny Rubin, Marc Brodine, Rossana Cambron, Arturo Cambron, Luis Rivas, Rita Verner, Michele Artt, Scott Marshall, and Betty Smith.