Chapter Seven: Towards the Comprehensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOUTIQUE BUILDING AVAILABLE for LEASE, 7,199 SF in Near North Side Building at Southeast Corner of Clark and Chestnut Streets ENTIRE BUILDING AVAILABLE for LEASE

WEST CHESTNUT STREET BOUTIQUE BUILDING AVAILABLE FOR LEASE, 7,199 SF in Near North Side Building at Southeast Corner of Clark and Chestnut Streets ENTIRE BUILDING AVAILABLE FOR LEASE UP 60' - 3 1/2" 60' - 5" FIRE CONTROL ROOM 56' - 0" OFFICE 9' - 8 1/8" 8 - 9' 42' - 8 1/4" 14' - 3 3/8" MECHANICAL ROOM 26' - 11 3/4" 11 - 26' OFFICE 29' - 6 7/8" 6 - 29' 9' - 6 3/4" 6 - 9' 40' - 7 7/8" 7 - 40' 36' - 11 1/4" 11 - 36' 40' - 10 1/2" 40' - 10 CLOSET CHASE ELEVATOR ELEVATOR DN OFFICE 9' - 7 3/4" 7 - 9' ELEVATOR MACHINE ROOM 7/8" 7 - 7' 8' - 3 1/2" 3 - 8' 6' - 3 7/8" 3 - 6' STORAGE STORAGE UP 14' - 6 1/4" UP 12' - 7 7/8" 9' - 0" SCALE: 3/16"=1'-0" SCALE: 3/16"=1'-0" 0' 2'-8" 5'-4" 0' 2'-8" 5'-4" 77 WEST CHESTNUT LOWER LEVEL EXISTING PLAN X00 77 WEST CHESTNUT LEVEL 1 EXISTING PLAN X01 833 N Clark St. 10/21/15833 N Clark St. 10/21/15 Chicago, IL 60610 Lower Level NO. DATE DESCRIPTION Chicago, IL 60610 Level 1 Office/Retail Space NO. DATE DESCRIPTION 833 NORTH CLARK LLC - --/--/-- ----- 833 NORTH CLARK LLC - --/--/-- ----- 1110 JORIE BLVD., SUITE #300 - --/--/-- ----- 1110 JORIE BLVD., SUITE #300 - --/--/-- ----- OAKBROOK, IL 60523 OAKBROOK, IL 60523 - --/--/-- ----- - --/--/-- ----- 1,499 SF C:\Users\cchan\Documents\833 Clark Apartments_AA_ANNEX_ORIGINAL_cchan.rvt 11/9/2015 5:33:58 PM Approximately 1,900 SF C:\Users\cchan\Documents\833 Clark Apartments_AA_ANNEX_ORIGINAL_cchan.rvt 11/9/2015 5:33:59 PM 60' - 3 1/2" 60' - 3 1/2" OPERABLE CASEMENT WINDOW DOUBLE HUNG WINDOW DOUBLE HUNG WINDOW OPERABLE CASEMENT WINDOW DOUBLE HUNG WINDOW DOUBLE HUNG WINDOW -

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage Bus routes operating out of the North Park Garage run primarily throughout the Loop/CBD and Near Northside areas, into the city’s Northeast Side as well as Evanston and Skokie. Buses from this garage provide access to multiple rail lines in the CTA system. 2 North Park Garage North Park bus routes are some busiest in the CTA system. North Park buses travel through some of Chicago’s most upscale neighborhoods. ● 280+ total buses ● 22 routes Available Media Interior Cards Fullbacks Brand Buses Fullwraps Kings Ultra Super Kings Queens Window Clings Tails Headlights Headliners Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. Do not share North Park Garage Commuter Profile Gender Age Female 60.0% 18-24 12.5% Male 40.0% 25-44 49.2% 45-64 28.3% Employment Status 65+ 9.8% Residence Status Full-Time 47.0% White Collar 50.1% Own 28.9% 0 25 50 Management, Business Financial 13.3% Rent 67.8% HHI Professional 23.7% Neither 3.4% Service 14.0% <$25k 23.6% Sales, Office 13.2% Race/Ethnicity $25-$34 11.3% White 65.1% Education Level Attained $35-$49 24.1% African American 22.4% High School 24.8% Hispanic 24.1% $50-$74 14.9% Some College (1-3 years) 21.2% Asian 5.8% >$75k 26.1% College Graduate or more 43.3% Other 6.8% 0 15 30 Source: Scarborough Chicago Routes # Route Name # Route Name 11 Lincoln 135 Clarendon/LaSalle Express 22 Clark 136 Sheridan/LaSalle Express 36 Broadway 146 Inner Drive/Michigan Express 49 Western 147 Outer Drive Express 49B North Western 148 Clarendon/Michigan Express X49 Western Express 151 Sheridan 50 Damen 152 Addison 56 Milwaukee 155 Devon 82 Kimball-Homan 201 Central/Ridge 92 Foster 205 Chicago/Golf 93 California/Dodge 206 Evanston Circulator 96 Lunt Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. -

Moody Theological Seminary

MOODY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 2010–2011 CATALOG FROM THE WORD. TO LIFE. M OODY T HEOLOGICAL S E M INARY CATALOG 2010–2011 M OODY T HEOLOGICAL S E M INARY 820 N. LaSalle Blvd. Chicago, IL 60610-4376 FAX: 312.329.4344 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.moody.edu Admissions Office 800.967.4MBI 312.329.4400 M OODY T HEOLOGICAL S E M INARY —M ICHIGAN 41550 E. Ann Arbor Trail Plymouth, MI 48170-4308 734.207.9581 www.mts.edu WELCOME! You have picked up this catalog because you are considering semi- nary education. I applaud your decision! Graduate-level theological education will equip, shape, and mold you for a lifetime of effective ministry. Moody Theological Seminary is uniquely positioned to train you for ministry in our rapidly changing world. With campuses in both Chi- cago and Michigan, we offer you options that are rooted deeply in the Bible and provide you with ministry skills geared for today’s society. Want training in urban ministry? We can do that. Want classes in the biblical languages and exegesis? We can do that too. Want course- work leading to counseling certification? Moody is the answer. For whatever ministry role you envision in the future, Moody Theological Seminary can provide you with the training you desire. As you consider further education and service to our Lord, I encour- age you to make Moody your destination. Please let us know how we can serve you and your educational needs. Only by His grace, J. Paul Nyquist, PhD President 3 DEAR BROTHERS AND SIstERS IN CHRIst JESUS, Ezra understood the nature of his times. -

ICCAP: Amounts for Three Scheduled Distributions and Totals by Grantee

ICCAP: Amounts for Three Scheduled Distributions and Totals by Grantee First Second Third First Second Third Institution Name Institution Name Distribution Distribution Distribution Total Distribution Distribution Distribution Total June 2010 May 2012 Sept 2013 June 2010 May 2012 Sept 2013 Adler School of Prof. Psychology $ 247,525 $ 518,455 $ 379,515 $ 1,145,495 Monmouth College $ 495,049 $ 1,036,911 $ 954,172 $ 2,486,132 Augustana College 495,049 1,036,911 1,374,451 2,906,411 Moody Bible Institute 495,049 1,036,911 642,841 2,174,801 Aurora University 495,049 1,036,911 1,641,652 3,173,612 Morrison Institute of Technology 49,505 103,691 94,383 247,579 Benedictine University (see notes) 495,049 1,036,911 1,711,296 3,243,256 National University of Health Sciences 495,049 1,036,911 816,951 2,348,911 Blackburn College 495,049 1,036,911 689,385 2,221,345 National-Louis University 495,049 1,036,911 1,570,628 3,102,588 Bradley University 1,237,623 2,592,278 3,023,261 6,853,162 North Central College 495,049 1,036,911 1,351,696 2,883,656 Chicago School of Prof. Psych (see notes) 76,101 - - 76,101 North Park University 495,049 1,036,911 1,241,369 2,773,329 Columbia College Chicago 1,237,623 2,592,278 4,982,958 8,812,859 Northwestern University 1,237,623 2,592,278 7,467,401 11,297,302 Concordia University 495,049 1,036,911 1,322,046 2,854,006 Olivet Nazarene University 495,049 1,036,911 1,575,455 3,107,415 DePaul University 1,237,623 2,592,278 8,152,123 11,982,024 Principia College (see notes) - - - - Dominican University 495,049 1,036,911 1,287,913 -

Adjunct Faculty 1

Adjunct Faculty 1 ADJUNCT FACULTY MBA, DePaul University Wayne Corapi, PhD Adjunct faculty members are part-time teaching faculty who teach one or Lecturer in Biology, 2016 more classes on an occasional basis. The degree to which adjunct faculty BA, University of Colorado participate in daily campus life is limited. They are appointments of the DVM, College of Veterinarian Medicine, Colorado State University Dean of the College. The date that follows the listing of each adjunct MS, Seattle Pacific University indicates the beginning year of service at Trinity. ThM, MCS, Regent College PhD, NY State College of Veterinarian Medicine, Cornell University Allison Alcorn, PhD Lecturer in Music, 1998 Ward H. Cushman, MDiv BA, Wheaton College Lecturer in Bible, 2013 PhD, University of North Texas BA, Simpson College MDiv, Western Seminary Susan Alford, PhD Adjunct Professor of Education Alex Daye, MA BS, Wheaton College Lecturer in Graphic Design, 2016 MS, PhD, University of Nebraska BFA, Barry University MA, Savannah College of Art and Design Rich Allen, MBA Lecturer in Business, 2016 David Dillon, EdD BA, Trinity International University Lecturer in Psychology, 2016 MBA, Lake Forest Graduate School BA, Judson College BA, Aurora University Sherry Bengsch, MA MSEd, EdD, Northern Illinois University Lecturer in English, Waupun 2018 BS, MA, Marian University Chris Donato, MA Lecturer in Communication, 2021 Matt Boutilier, PhD BS, Journalism, John Brown University Lecturer in Biblical and Religious Studies, 2012 BA, English Literature, John Brown -

Alumni News Class Notes from Alumni of Moody Bible Institute

MOODY Winter 2013 Alumni News Class Notes from Alumni of Moody Bible Institute Challenged to Serve STUDENTS COMMIT TO CROSS-CULTURAL MINISTRY (Page 4) MoodyHighlights Dear friends, The Gary D. Chapman Chair for Marriage and Family Established I am amazed and thankful for what God has done as I Well-known Moody In addition, he serves as senior associate reflect on the past few months since the beginning of the alumnus and author pastor at Calvary Baptist Church in school year. I hope you’ll be encouraged about the news of the New York Times Winston-Salem, North Carolina. bestseller The 5 Love of a new endowed chair, growing enrollments, and student Dr. Chapman holds B.A. and M.A. Languages, Dr. Gary commitments to service at Missions Conference. I think degrees in anthropology from Wheaton Chapman ’58, and you will also be inspired, as I was, when you read about College and Wake Forest University, his wife, Karolyn, Moody alumni who are serving in inner city ministries and about five Moody respectively. He received M.R.E. and gave an endowment alumni who are working together in Haiti. Ph.D. degrees from Southwestern that established The Gary D. Chapman Baptist Theological Seminary and Chair for Marriage and Family, the first As we look forward to what God will do in the new year, I ask for your help completed postgraduate work at the in Moody’s 126-year history. The Moody in influencing the future of the Alumni Association with your vote for the University of North Carolina and Duke Theological Seminary (MTS) chair will Alumni Board of Directors (see insert card). -

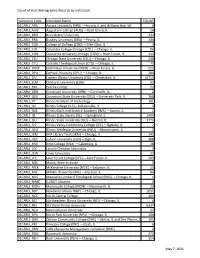

Count of Host Bibliographic Records by Institution

Count of Host Bibliographic Records by Institution Institution Code Institution Name COUNT 01CARLI_ARU Aurora University (ARU) —Aurora, IL and Williams Bay, WI 6 01CARLI_AUG Augustana College (AUG) —Rock Island, IL 16 01CARLI_BEN Benedictine University 332 01CARLI_BRA Bradley University (BRA) —Peoria, IL 144 01CARLI_COD College of DuPage (COD) —Glen Ellyn, IL 3 01CARLI_COL Columbia College Chicago (COL) —Chicago, IL 86 01CARLI_CON Concordia University Chicago (CON) —River Forest, IL 133 01CARLI_CSU Chicago State University (CSU) —Chicago, IL 348 01CARLI_CTU Catholic Theological Union (CTU) —Chicago, IL 79 01CARLI_DOM Dominican University (DOM) —River Forest, IL 212 01CARLI_DPU DePaul University (DPU) —Chicago, IL 280 01CARLI_EIU Eastern Illinois University (EIU) —Charleston, IL 16713 01CARLI_ELM Elmhurst University (ELM) 92 01CARLI_ERK Eureka College 22 01CARLI_GRN Greenville University (GRN) —Greenville, IL 2 01CARLI_GSU Governors State University (GSU) —University Park, IL 160 01CARLI_IIT Illinois Institute of Technology 191 01CARLI_ILC Illinois College (ILC)—Jacksonville, IL 3 01CARLI_IMS Illinois Math and Science Academy (IMS) —Aurora, IL 1 01CARLI_ISL Illinois State Library (ISL) —Springfield, IL 1495 01CARLI_ISU Illinois State University (ISU) —Normal, IL 3775 01CARLI_IVC Illinois Valley Community College (IVC) —Oglesby, IL 7 01CARLI_IWU Illinois Wesleyan University (IWU) —Bloomington, IL 3 01CARLI_JKM JKM Library Trust (JKM) —Chicago, IL 345 01CARLI_JUD Judson University (JUD) —Elgin, IL 388 01CARLI_KNX Knox College (KNX) —Galesburg, -

Moody Bible Institute 7:00 P.M. Lindner Fitness Center

#50 Tiana Forrest Gameday December 5, 2009 Moody Bible Institute 7:00 p.m. Lindner Fitness Center women’s basketball schedule women’s basketball schedule judson university eagles (elgin, illinois) moody bible institute archers (chicago, illinois) 2009-10 Probable Starters Probable Starters 2009-10 Date Opponent Result No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. PPG RPG No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. PPG RPG Date Opponent Result Nov. 5 VITERBO (WI) L, 66-50 Nov. 12 Madonna L, 78-38 Nov. 9 @ Western Illinois (exh) L, 68-30 13 Kirstin Johns G 5-7 Sr. 11.0 3.9 12 Christina Classen F 6-2 Sr. 23 ShaRhonda Huff F 5-10 Fr. 7.6 3.3 Nov. 14 Andrews W, 68-51 Nov. 12 #17 AQUINAS L, 91-47 15 Sarah Sparks G 5-6 Fr. Nov. 20 Grace Bible W, 74-43 Nov. 14 ST. MARY of the Woods L, 89-85 OT 32 Alicia Rovertoni F 6-0 Sr. 13.5 10.7 22 Emily Sparks G 5-3 Sr. Nov. 24 Trinity Christian L, 73-51 Nov. 18 @ Ashford L, 57-37 33 Rachel McBride F 5-11 Fr. 4.1 5.6 30 Stephanie Homontowski G 5-4 Fr. Dec. 3 Indiana-NW L, 70-39 Nov. 20 HOLY CROSS ! W, 66-45 50 Tiana Forrest F 6-0 Sr. 3.7 4.7 42 Jacqui Mitchell F 6-2 So. Dec. 5 Judson 7:00 p.m. Nov. 21 INDIANA-NW ! W, 68-60 Dec. 10 MARIAN 7:00 p.m. Nov. 24 @ #8 St. Xavier L, 78-40 No. -

The American Bible College: an Eye to the Future

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1996 The American Bible College: An Eye to the Future Larry J. Davidhizar Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Davidhizar, Larry J., "The American Bible College: An Eye to the Future" (1996). Dissertations. 3615. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3615 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1996 Larry J. Davidhizar LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE AMERICAN BIBLE COLLEGE: AN EYE TO THE FUTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND POLICY STUDIES BY LARRY J. DAVIDHIZAR CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 1996 Copyright by Larry James Davidhizar, 1996 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was made possible by the loving encouragement of Dona, Jamie, Brian and Ben-my wife and children. The financial commitment by the administration of the Moody Bible Institute was greatly appreciated as was the professional and pastoral support provided by F. Michael Perko, S.J. Thanks must also be expressed to the many Bible college administrators and faculty members who provided time, information, and even food and lodging for this study. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii Chapter 1. -

Moody Alumni News 2018 Winter

MOODY Alumni News Winter 2018 Hope Never Ends Three Moody Aviators Remembered by Their Wives From the Executive Director Dear friends, Some Christians live long lives of service. Others finish their work on earth much too soon, while still in their prime. In this issue, you’ll hear from Dr. Gene Getz—still going strong for the Lord in his 80s—and from three young widows whose husbands died in a Moody Aviation plane accident last July. You’ll read about an alumna who’s redeeming the There is a time lives of sex-trafficked women and another who provides jobs for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. for everything. “There is a time for everything,” Solomon wrote in Ecclesiastes . “a time to be born and a time to die, a time to plant and a time to uproot” (3:1–2). As we celebrate the birth of our Savior, we remember that Christ was born to die—yet his resurrection assures us that we too will rise, along with our loved ones who love the Lord. Serving Christ together, Nancy (Andersen ’80) Hastings Executive Director, Moody Alumni Association P.S. I hope to see you during Founder’s Week—and Alumni Day on Friday, February 8! And don’t miss a tour of the new Chapman Center on campus. The Alumni Association appreciates the variety of news it receives from alumni. Due to space and other restrictions, it may not be possible to publish all of the announcements we receive. Moody Alumni News, Winter 2018 (Vol. 68, No. 3): Executive Director: Nancy (Andersen ’80) Hastings; Managing Editor: Linda Piepenbrink; Art Director: Lynn Gabalec; Alumni Notes Editor: Loren Joseph ’18; Alumni Board of Directors: Cherie (Bruchan ’75) Balog, Tobias Brown ’05, Chris Drombetta ’14, Steve Dutton ’86, Peter Grant ’83, Col. -

2017 Annual Report Table of Contents

The Power of We. THE CHICAGO COMMUNITY TRUST 2017 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS In Appreciation: Terry Mazany . 2 Year in Review . 4 Our Stories: Philanthropy in Action . 8 In Memoriam . 20 Competitive Grants . 22 Grants from the Searle Funds at The Chicago Community Trust . 46 Searle Scholars . 47 Donor Advised Grants . 48 Designated Grants . 76 Matching Gifts . 77 Grants from Identity-Focused Funds . 78 Grants from Supporting Organizations . 80 Grants from Collaborative Funds . 84 Funds of The Chicago Community Trust and Affiliates . 87 Contributors to Funds at The Chicago Community Trust and Affiliates . 99 The 1915 Society . 108 Professional Advisory Committee and Young Professional Advisory Committee . 111 Financial Highlights . 112 Executive Committee . 116 Trustees Committee and Banks . 117 The Chicago Community Trust Staff . 118 Trust at a Glance . 122 The power to reach. The power to dream. The power to build, uplift and create. The power to move the immovable, to align our reality to the best of our ideals. That is the power of we. We know that change doesn’t happen in silos. From our beginning, The Chicago Community Trust has understood that more voices, more minds, more hearts are better than one. It is our collective actions, ideas and generosity that propel us forward together. We find strength in our differences, common ground in our unparalleled love for our region. We take courage knowing that any challenge we face, we face as one. We draw power from our shared purpose, power that renews and emboldens us on our journey – the world-changing power of we. Helene D. -

Catalog 2013–2014

M OODY T HEOLOGICAL S E M INARY AND G RADUA T E S CHOOL CATALOG 2013–2014 M OODY T HEOLOGICAL S E M INARY AND G RADUA T E S CHOOL 820 N. LaSalle Blvd. Chicago, IL 60610-4376 FAX: 312.329.4344 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.moody.edu/seminary Admissions Office 800.967.4MBI 312.329.4400 M OODY T HEOLOGICAL S E M INARY AND G RADUAT E S CHOOL —M ICHIGAN 41550 E. Ann Arbor Trail Plymouth, MI 48170-4308 734.207.9581 www.moody.edu/seminary WELCOME! You have picked up this catalog because you are considering seminary education. I applaud your decision! Graduate-level theological education will equip, shape, and mold you for a lifetime of effective ministry. Moody Theological Seminary is uniquely positioned to train you for ministry in our rapidly changing world. With campuses in both Chicago and Michigan, we offer you options that are rooted deeply in the Bible and provide you with ministry skills geared for today’s society. Want training in urban ministry? We can do that. Want classes in the biblical languages and exegesis? We can do that too. Want coursework leading to counseling certification? Moody is the answer. For whatever ministry role you envision in the future, Moody Theological Seminary can provide you with the training you desire. As you consider further education and service to our Lord, I encourage you to make Moody your destination. Please let us know how we can serve you and your educational needs. Only by His grace, J.