The Arabic Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Holy Father RAPHAEL Was Born in Syria in 1860 to Pious Orthodox Parents, Michael Hawaweeny and His Second Wife Mariam

In March of 1907 Saint TIKHON returned to Russia and was replaced by From his youth, Saint RAPHAEL's greatest joy was to serve the Church. When Archbishop PLATON. Once again Saint RAPHAEL was considered for episcopal he came to America, he found his people scattered abroad, and he called them to office in Syria, being nominated to succeed Patriarch GREGORY as Metropolitan of unity. Tripoli in 1908. The Holy Synod of Antioch removed Bishop RAPHAEL's name from He never neglected his flock, traveling throughout America, Canada, and the list of candidates, citing various canons which forbid a bishop being transferred Mexico in search of them so that he might care for them. He kept them from from one city to another. straying into strange pastures and spiritual harm. During 20 years of faithful On the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1911, Bishop RAPHAEL was honored for his 15 ministry, he nurtured them and helped them to grow. years of pastoral ministry in America. Archbishop PLATON presented him with a At the time of his death, the Syro-Arab Mission had 30 parishes with more silver-covered icon of Christ and praised him for his work. In his humility, Bishop than 25,000 faithful. The Self-Ruled Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of RAPHAEL could not understand why he should be honored merely for doing his duty North America now has more than 240 U.S. and Canadian parishes. (Luke 17:10). He considered himself an "unworthy servant," yet he did perfectly Saint RAPHAEL also was a scholar and the author of several books. -

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO

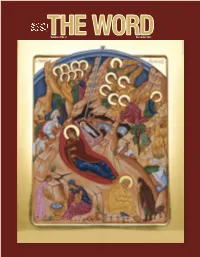

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO. 9 DECEMBER 2017 COVER: ICON OF THE NATIVITY EDITORIAL Handwritten icon by Khourieh Randa Al Khoury Azar Using old traditional technique contents [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL CELEBRATING CHRISTMAS by Bishop JOHN 5 PLEADING FOR THE LIVES OF THE DEFINES US PEOPLE OF THE MIDDLE EAST: THE U.S. VISIT OF HIS BEATITUDE PATRIARCH JOHN X OF ANTIOCH EVERYONE SEEMS TO BE TALKING ABOUT IDENTITY THESE DAYS. IT’S NOT JUST AND ALL THE EAST by Sub-deacon Peter Samore ADOLESCENTS WHO ARE ASKING THE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION, “WHO AM I?” RATHER, and Sonia Chala Tower THE QUESTION OF WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN IS RAISED IMPLICITLY BY MANY. WHILE 8 PASTORAL LETTER OF HIS EMINENCE METROPOLITAN JOSEPH PHILOSOPHERS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE ADDRESSED THIS QUESTION OF HUMAN 9 I WOULD FLY AWAY AND BE AT REST: IDENTITY OVER THE YEARS, GOD ANSWERED IT WHEN THE WORD BECAME FLESH AND THE LAST PUBLIC APPEARANCE AND FUNERAL OF DWELT AMONG US. HE TOOK ON OUR FLESH SO THAT WE MAY PARTICIPATE IN HIS HIS GRACE BISHOP ANTOUN DIVINITY. CHRIST REVEALED TO US WHO GOD IS AND WHO WE ARE TO BE. WE ARE CALLED by Sub-deacon Peter Samore 10 THE GHOST OF PAST CHRISTIANS BECAUSE HE HAS MADE US AS LITTLE CHRISTS BY ACCEPTING US IN BAPTISM CHRISTMAS PRESENTS AND SHARING HIMSELF IN US. JUST AS CHRIST REVEALS THE FATHER, SO WE ARE TO by Fr. Joseph Huneycutt 13 RUMINATION: ARE WE CREATING REVEAL HIM. JUST AS CHRIST IS THE INCARNATION OF GOD, JOINED TO GOD WE SHOW HIM OLD TESTAMENT CHRISTIANS? TO THE WORLD. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Postcolonial Syria and Lebanon

Post-colonial Syria and Lebanon POST-COLONIAL SYRIA AND LEBANON THE DECLINE OF ARAB NATIONALISM AND THE TRIUMPH OF THE STATE Youssef Chaitani Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Youssef Chaitani, 2007 The right of Youssef Chaitani to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. ISBN: 978 1 84511 294 3 Library of Middle East History 11 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Minion by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword ix Introduction 1 1The Syrian Arab Nationalists: Independence First 14 A. The Forging of a New Alliance 14 B. -

Yahya Ibn „Adi on Psychotherapy

Available online at www.globalilluminators.org GlobalIlluminators FULL PAPER PROCEEDING Multidisciplinary Studies Full Paper Proceeding ETAR-2014, Vol. 1, 60-69 ISBN: 978-969-9948-07-7 ETAR 2014 Yahya Ibn „Adi On Psychotherapy Mohd. Nasir Omar1*, Dr. Zaizul Ab Rahman2 1,2National University of Malaysia, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia. Abstract Among Christian scholars who especially distinguished themselves in the 10th/11th century Islamic Baghdad were Yahya Ibn „Adi (d.974), Ibn Zur„ah (d.1008), Ibn al-Khammar (d.1017) and Abu „Ali al-Samh (d.1027). Some of these Christian translators were no longer relying on the Caliphs or other patrons of learning, but often found their own means of living which in turn prolonged their own academic interest. Consequently, some of them were no mere translators any more, but genuine scholars. The chief architect among them was Yahya Ibn „Adi. He was not only the leader of his group but was also dubbed as the best Christian translator, logician and theologian of his times. This is justified, in addition, by his ample productivity in those fields of enquiry. A considerable number of such works have evidently been used by contemporary and later writers, an d have also reached us today. Hence we consider that it is in these aspects that his distinctive contributions to scholarship lie, and therefore he deserves more serious study. Thus, this qualitative study which applies conceptual content analysis method, seeks to make an analytical study of Yahya Ibn „Adi‟s theory of psychotherapy as reflected in his major work on ethics, Tahdhib al-Akhlaq (The Refinement of Character). -

118102 JAN. 2009 WORD.Indd

Volume 53 No. 1 January 2009 VOLUME 53 NO. 1 JANUARY 2009 contents COVER THEOPHANY: The Baptism of Christ 3 EDITORIAL by Rt. Rev. John Abdalah 4 CANON 28 OF THE 4TH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL by Metropolitan PHILIP 10 METROPOLITAN PHILIP HOSTS ANTIOCHIAN SEMINARIANS IN ANNUAL EVENT 14 FR. FRED PFEIL INTERVIEWS FR. DAVID ALEXANDER, The Most Reverend US NAVY CHAPLAIN Metropolitan PHILIP, D.H.L., D.D. Primate 17 DEPARTMENT OF YOUTH MINISTRIES The Right Reverend Bishop ANTOUN 21 ORATORICAL FESTIVAL The Right Reverend Bishop JOSEPH The Right Reverend 23 COMMUNITIES IN ACTION Bishop BASIL The Right Reverend 31 ORTHODOX WORLD Bishop THOMAS The Right Reverend 35 THE PEOPLE SPEAK … Bishop MARK The Right Reverend Bishop ALEXANDER Icons courtesy of Come and See Icons. Founded in Arabic as www.comeandseeicons.com Al Kalimat in 1905 by Saint Raphael (Hawaweeny) Founded in English as The WORD in 1957 by Metropolitan ANTONY (Bashir) Editor in Chief The Rt. Rev. John P. Abdalah, D.Min. Assistant Editor Christopher Humphrey, Ph.D. Editorial Board The Very Rev. Joseph J. Allen, Th.D. Anthony Bashir, Ph.D. The Very Rev. Antony Gabriel, Th.M. The Very Rev. Peter Gillquist Letters to the editor are welcome and should include the author’s full name and Ronald Nicola parish. Submissions for “Communities in Action” must be approved by the local Najib E. Saliba, Ph.D. pastor. Both may be edited for purposes of clarity and space. All submissions, in The Very Rev. Paul Schneirla, M.Div. hard copy, on disk or e-mailed, should be double-spaced for editing purposes. -

The Life of Yahya Ibn 'Adi: a Famous Christian Philosopher of Baghdad

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 2 S5 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy April 2015 The Life of Yahya Ibn ‘Adi: A Famous Christian Philosopher of Baghdad Mohd. Nasir Omar Department of Theology and Philosophy, Faculty of Islamic Studies, National University of Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n2s5p308 Abstract Among Christian translators who especially distinguished themselves in the 10th/11th century Baghdad were Yahya Ibn ‘Adi (d.974), Ibn Zur‘ah (d.1008), Ibn al-Khammar (d.1017) and Abu ‘Ali al-Samh (d.1027). Some of these Christians were no longer relying on the Caliphs or other patrons of learning, but often found their own means of living which in turn prolonged their own academic interest. Consequently, some of them were no mere translators any more, but genuine scholars. The chief architect among them was Yahya Ibn ‘Adi. He was not only the leader of his group but was also dubbed as the best Christian translator, logician and theologian of his times. This is justified, in addition, by his ample productivity in those fields of enquiry. A considerable number of such works have evidently been used by contemporary and later writers, and have also reached us today. Hence we consider that it is in these aspects that his distinctive contributions to scholarship lie, and therefore he deserves more serious study. Thus, this qualitative study which uses content analysis method seeks to introduce Yahya Ibn ‘Adi in terms of his history, life, career, education and writings. -

The Holy Hieromartyr Joseph of Damascus and His Companions

the akolouthia for the commemoration of The Holy Hieromartyr Joseph of Damascus and his Companions (+ 10 July 1860) The work of the Nun Mariam (Zaka) Abbess of the Holy Monastery of St John the Baptist Douma El-Batroun Lebanon Original Arabic Text 1993 – English Translation 2008 TYPIKON If the commemoration FALLS ON a Sunday AT GREAT VESPERS on Saturday evening, after the Proëmiakon (Ps. 103) Bless the Lord, O my soul and the 1st Kathisma of the Psalter (Pss. 1-8) Blessed is the man, we chant Lord, I have cried in the tone of the week with six stichera for the Resurrection in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos and four stichera for the Saints, Glory for the Saints, and Both Now and the first Theotokíon in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos. After the Entrance with the censer we chant O gladsome Light followed by the Prokeimenon of the day The Lord is King and the three lessons for the Saints. At the Aposticha we chant all of the stichera for the Resurrection in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos, Glory for the Saints, and Both Now and the Theotokíon in tone 8 from the Octoëchos. At the Apolytikia we chant that of the Resurrection in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos, Glory and that of the Saints, and Both Now and the Resurrectional Theotokíon in tone 5 from the Octoëchos. The Great Dismissal as usual. AT THE MIDNIGHT OFFICE on Sunday morning, we chant the Triadikos Canon in the tone of the week from the Octoëchos, the Litiya Troparia for the Saints, followed by It is truly meet to laud the transcendent Trinity and the other Megalynaria. -

Ghassanid’ Abokarib

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 16.1, 15-35 © 2013 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press A SYRIAC CODEX FROM NEAR PALMYRA AND THE ‘GHASSANID’ ABOKARIB FERGUS MILLAR ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, OXFORD ABSTRACT This paper concerns a Syriac codex copied near Palmyra in the mid- sixth century, whose colophon, printed and translated, refers to the ‘monophysite’ bishops, Jacob and Theodore, and to ‘King’ Abokarib. It explores the evidence for the spread of the use of Syriac in the provinces of Phoenicia Libanensis and Arabia, and the implications of the reference to Abokarib, questioning whether ‘Ghassanid’ is an appropriate term for the family to which he belonged. INTRODUCTION This paper takes as its primary topic a Syriac codex containing a translation of some of John Chrysostom’s homilies on the Gospel of Matthew which was copied in a monastery near Palmyra in the middle decades of the sixth century, and discusses the political and religious context which is revealed in a note by the scribe at the end. This colophon, printed by Wright in his great Catalogue of Syriac manuscripts in the British Museum, published in 1870-2, seems never to have been re-printed since, and is reproduced below along with an English translation. 15 16 Fergus Millar In the wider perspective which needs to be sketched out first, the codex is very significant for the history of language-use in the Late Roman Near East, for it is a very rare item of evidence for the writing of Syriac in the Palmyrene region. As we will see below, there is also some, if only slight, evidence for the use of Syriac further south in the province of Phoenicia Libanensis, namely in the area of Damascus, and also in the Late Roman province of ‘Arabia’. -

The Arabic Language and the Bible

Page 1 of 8 Original Research The identity and witness of Arab pre-Islamic Arab Christianity: The Arabic language and the Bible Author: This article argues that Arab Christianity has had a unique place in the history of World David D. Grafton Christianity. Rooted in a biblical witness, the origins and history of Arab Christianity have Affiliations: been largely forgotten or ignored. This is not primarily as a result of the fact that the Arab 1The Lutheran Theological Christian historical legacy has been overcome by Islam. Rather, unlike other early Christian Seminary at Philadelphia, communities, the Bible was never translated into the vernacular of the Arabs. By the 7th century United States of America the language of the Qur’an became the primary standard of the Arabic language, which 2Department of New then became the written religious text of the Arabs. This article will explore the identity and Testament Studies, Faculty witness of the Christian presence in Arabia and claims that the development of an Arabic Bible of Theology, University of provides a unique counter-example to what most missiologists have assumed as the basis for Pretoria, South Africa. the spread of the Christian faith as a result of the translation of the Christian scriptures into a Note: vernacular. The Reverend Dr David D. Grafton is Associate Professor of Islamic Studies and Christian-Muslim Introduction Relations and Director of Graduate Studies at The Great Missionary Age (1792–1914) has been viewed by many Protestant and Evangelical the Lutheran Theological churches in Western Europe and North America as a time through which God provided an Seminary in Philadelphia opportunity to evangelise the whole world.This was done primarily through the translation, (USA). -

July/August 2012

a St. Gregory’s Journal a July/August, 2012 - Volume XVII, Issue 7 St. Gregory the Great Orthodox Church - A Western Rite Congregation of the Antiochian Archdiocese o human being can worthily praise the holy passing of the Mother of God - not if he had ten thousand tongues Nand as many mouths! Even if all the tongues of the world’s scattered inhabitants came together, they could not From a approach a praise that was fitting. It simply lies beyond the realm of oratory. But since God loves what we offer, out of homily of longing and eagerness and good intentions, as best we know Saint John of how, and since what pleases her Son is also dear and delightful to God’s mother, come, let us again grope for words of praise... Damascus et the heavens rejoice now, and the angels applaud; let the died AD 760AD Learth be glad now [Ps. 96:911; 97:1], and all men and feast day - March 27 women leap for joy! Let the air ring out now with happy song, and let the black night lay aside its gloomy, unbecoming cloak of darkness, to imitate the bright radiance of day in sparkles of flame. For the living city of the Lord God of hosts is lifted up, and kings bring a priceless gift from the temple of the Lord, the wonder of Sion to the Jerusalem on high who is free and is their mother [Gal. 4:26]; those who were appointed by Christ as rulers of all the earth - the Apostles - escort to heaven the ever-virgin Mother of God! Inside: he Apostles were scattered everywhere on this earth, fishing for men and women with the varied and sonorous St. -

Sixth Century*

THE MARTYRS OF NAJRAN AND THE END OF THE YIMYAR: ON ?HE POLITICAL HISTORY OF SOUTH ARABIA IN THE EARL?' SIXTH CENTURY* Norbert Nebes Introduction In the spring of the year 519, or perhaps even as early as the preced- ing autumn,' an Alexandrian spice trader named CosmasZtraveling to Taprobane (known today as Sri Lanka) arrived at the ancient Port city of Adulis on the African side of the Red Sea, where he made a short ~tay.~In Cosmas' day, Adulis controlled the Bäb al-Mandab and maintained close ties with the commerciai centers along the South Arabian coast; it attracted merchants from Alexandria and Ailat, and it was from them that Cosmas hoped to obtain valuable information for his journey onward to India. Yet at this point in his account of the journey, Cosmas makes no mention of spices or other commodi- ties. His attention is focused on matters of classical philology. * 'ihe aim of this paper is to provide an oveniew of the political history of the events which took place in the period under discussion. It makes no daim to be a complete review of ail the sources available or to consider the current discussion exhaustively. For such a synopsis, See the recer,t contribution by Beaucamp et al., "Perseicution," which emphasizes the chronology of events, and which I shaii follow in placing the Start of the Himyarite era in the year 110 BCE. Müller, "Himyar," gives a thorough evaluation of the source material then available and remainc z fundamen- tal work-nie sigla of inscriptions cited follow Stein, Untersuchungen, 274-290.