An Exploration of the Tension Between Illusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

The First Critical Assessments of a Streetcar Named Desire: the Streetcar Tryouts and the Reviewers

FALL 1991 45 The First Critical Assessments of A Streetcar Named Desire: The Streetcar Tryouts and the Reviewers Philip C. Kolin The first review of A Streetcar Named Desire in a New York City paper was not of the Broadway premiere of Williams's play on December 3, 1947, but of the world premiere in New Haven on October 30, 1947. Writing in Variety for November 5, 1947, Bone found Streetcar "a mixture of seduction, sordid revelations and incidental perversion which will be revolting to certain playgoers but devoured with avidity by others. Latter category will predomin ate." Continuing his predictions, he asserted that Streetcar was "important theatre" and that it would be one "trolley that should ring up plenty of fares on Broadway" ("Plays Out of Town"). Like Bone, almost everyone else interested in the history of Streetcar has looked forward to the play's reception on Broadway. Yet one of the most important chapters in Streetcar's stage history has been neglected, that is, the play's tryouts before that momentous Broadway debut. Oddly enough, bibliographies of Williams fail to include many of the Streetcar tryout reviews and surveys of the critical reception of the play commence with the pronouncements found in the New York Theatre Critics' Reviews for the week of December 3, 1947. Such neglect is unfortunate. Streetcar was performed more than a full month and in three different cities before it ever arrived on Broadway. Not only was the play new, so was its producer. Making her debut as a producer with Streetcar, Irene Selznick was one of the powerhouses behind the play. -

Producing Tennessee Williams' a Streetcar Named Desire, a Process

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF THEATRE PRODUCING TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, A PROCESS FOR DIRECTING A PLAY WITH NO REFUND THEATRE J. SAMUEL HORVATH Spring, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Finance with honors in Theatre Reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew Toronto Assistant Professor of Theatre Thesis Supervisor Annette McGregor Professor of Theatre Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT This document chronicles the No Refund Theatre production of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. A non-profit, student organization, No Refund Theatre produces a show nearly every weekend of the academic year. Streetcar was performed February 25th, 26th, and 27th, 2010 and met with positive feedback. This thesis is both a study of Streetcar as a play, and a guide for directing a play with No Refund. It is divided into three sections. First, there is an analysis Tennessee Williams’ play, including a performance history, textual analysis, and character analyses. Second, there is a detailed description of the process by which I created the show. And finally, the appendices include documentation and notes from all stages of the production, and are essentially my directorial promptbook for Streetcar. Most importantly, embedded in this document is a video recording of our production of Streetcar, divided into three “acts.” I hope that this document will serve as a road-map for -

(Mitch) Mitchell's Role in the Demise of Blanche Dubois in a Streetcar

Article Leviathan: Interdisciplinary Journal in English No. 2, 46-53 Harold (Mitch) © The Journal Editors 2018 Reprints and permissions: Mitchell’s role in the http://ojs.statsbiblioteket.dk/index.php/lev DOI: 10.7146/lev.v0i2.104695 demise of Blanche Recommendation: Arman Teymouri Niknam ([email protected]) Dubois in A Streetcar Literature in English 1: Form and Genre Named Desire Marie Lund ABSTRACT In Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire, Stanley Kowalski has often been seen as the main reason why Blanche DuBois mentally falls apart at the end of the play. This is emphasized by the fact that he rapes her and that she subsequently is committed to a mental institution. However, I find that the role of Harold (Mitch) Mitchell thereby is downplayed and underestimated. This article argues that he in fact is the real cause of Blanche’s psychological downfall. Critics such as Judith J. Thompson refer to Mitch as elevated to the romanticized ideal of Allan Grey, Blanche’s late husband. Blanche sees a potential new husband in Mitch, and when she realizes that he knows about her troubled past, she mentally collapses. While Stanley’s final act certainly is cruel and devastating, Mitch’s rejection of Blanche is what essentially sets off her final madness. Keywords: Tennessee Williams; gender roles; mental decline; madness; homosexuality; marriage; Literature in English 1: Form and Genre Corresponding author: Marie Lund ([email protected]) Department of English, Aarhus University 47 Introduction Marlon Brando was a so-called method actor and played the role of Stanley Kowalski both on Broadway in 1947 and in the screen adaption of A Streetcar Named Desire in 1951 (Palmieri). -

POETRY in the PLUMBING Stylistic Clash and Reconciliation in Recent American Stagings of a Streetcar Named Desire

Cercles 10 (2004) POETRY IN THE PLUMBING Stylistic Clash and Reconciliation in Recent American Stagings of A Streetcar Named Desire FELICIA HARDISON LONDRÉ University of Missouri-Kansas City Perhaps nothing suggests gritty naturalism quite so graphically as plumbing problems. Broken pipes and overflowing toilets are unpleasant realities that never had a place on stage before Emile Zola and André Antoine began reconfiguring audiences’ perceptions and expanding the bounds of what could be tolerated in art—that is, exposing bourgeois playgoers to the lower- class or seamy side of life. While today’s Broadway has embraced a musical titled Urinetown, we must remember that early twentieth-century American theatre audiences were slow to accept naturalism. Rarely was a sordid milieu depicted on the Broadway stage, nor was profane language heard there before the 1920s when Eugene O’Neill gave his sailors realistically salty dialogue and when What Price Glory portrayed soldiers swearing like soldiers. It was not until 1947, when Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire opened, that Broadway saw a play in which the bathroom figured so prominently in the setting, in the plot, and in the dialogue (including vocabulary like Stanley’s crude reference to his “kidneys”). While the plumbing that undergirds A Streetcar Named Desire may well be viewed as naturalistic, the play at the same time epitomizes Jacques Copeau’s concept of a poésie de théâtre; that is, it deploys a visual poetry of scenic metaphor, alongside the verbal poésie au théâtre. For example, the clouds of steam that emanate from the bathroom whenever Blanche takes a refreshing bath are realistic, but the haze on stage also creates an atmospheric softening effect. -

FIGHTING DUELS Stanley Vs. Blanche in the Trunk and Rape Sequences

Cercles 10 (2004) FIGHTING DUELS Stanley vs. Blanche in the Trunk and Rape Sequences ANNE-MARIE PAQUET-DEYRIS Université de Rouen It’s almost cliché to say that Blanche is a living figure of division. The basic dichotomy between her lofty aspirations and debasing bodily drives finds its expression in heavily polarized spaces and bodily movements, as well as verbal sparring scenes and actual physical duels in both film and play. In Elia Kazan’s adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s 1947 play however, shots and camera angles seem to particularly frame Blanche’s character as a highly vulnerable creature. She’s often shown in high angle shots and close-ups revealing the wear and tear of the various masks she puts on. Blanche is also often filmed in two-shots, with someone else looking down on her, and these two-shots very much resemble disturbing pas de deux between an eager female and an unreliable male. As Tennessee Williams writes in his Cat on a Hot Tin Roof “Notes for the Designer,” The designer should take as many pains to give the actors room to move about freely (to show their restlessness, their passion for breaking out) as if it were a set for a ballet. [14] The most striking representation of such a ballet is probably the forceful duo played by Blanche and Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire. And one should even say forced duo here, as this “ballet” is more akin to a forced march and even a dance of death than to any type of seductive tango or ritual rumba. -

Four Traces of the Streetcar

Cercles 10 (2004) FOUR TRACES OF THE STREETCAR DOMINIQUE SIPIÈRE Université du Littoral Four “physical traces” of A Streetcar Named Desire are currently available on tape or on DVD to enrich our reading of Kazan’s play of 1947. The 1984 remake is a little difficult to find, but Jessica Lange’s Blanche of 1995, or André Previn’s opera of 1998 are easily bought. I’ll start with the latter, premiered in San Francisco half a century after the first Broadway production, since it is both a radical example of a “filmed opera” and the most different reading to be compared with Kazan’s film. Extracts from the opera will suggest a few questions for further analysis. After the credits written on a staircase background and a short orchestral prelude based on a dissonant chord suggesting the tramway hoot and brutal desire itself, Blanche emerges from a mist, singing—apparently to the audience: They told me to take a streetcar named Desire; then transfer to the one called Cemeteries. Then to ride it for six blocks to Elysian Fields. This abrupt beginning and its minimal use of words is only possible because the San Francisco audience is already familiar with a play which has become an American landmark of theatrical culture. The setting itself is supposed to conjure up the “raffish” New Orleans atmosphere, but it is above all a reminder of most nineteenth-century operas such as Puccini’s La Bohème. Yet, as one goes on viewing the DVD, it becomes obvious that Blanche was not actually addressing the audience but Eunice, who was sitting on the staircase, on the left, but who remained invisible because of the limiting frame of the camera: this “filmed opera” is not—and cannot be—an “objective photograph” of the prestigious premiere performance given in 1998, as the spectators saw Eunice and they realized Blanche was addressing her. -

Hello Stanley, Good-Bye Blanche: the Brutal Asymmetries Of

Cercles 10 (2004) HELLO STANLEY, GOOD-BYE BLANCHE The Brutal Asymmetries of Desire in Production ROBERT F. GROSS Hobart and William Smith Colleges Staging A Streetcar Named Desire. Staging in the theater. Staging in film. Staging in theatrical histories, literary histories, memoirs. Staged by reviewers, literary critics, teachers and students, publishers and readers. Each one of us has personally staged Streetcar in the past, and will no doubt do so again. Our various stagings will merge, collide, fragment and metamorphose. Our stagings will inevitably be partial and informed by personal experience. Let me begin with my staging, and then move on to others.’ When I received Professor Guilbert’s kind invitation by e-mail to present a paper at this conference, my first response was on a level of hysteria, that easily rivaled Blanche. “No!” I thought, my heart racing. “There must be some mistake! I can’t talk about that play! I’m the last person on earth who should talk about that play!” Yes, it seemed impossible to me, for, though I have published articles on plays by Tennessee Williams, edited a volume of essays on Williams, and directed productions of three of his plays, I have done my best to avoid any involvement with what is his most celebrated play, teaching it in the classroom only once, avoiding the Kazan film until I reached age 47, and never once having seen a live production of the play. While Philip C. Kolin has edited a fine volume of essays entitled, Confronting ‘A Streetcar Named Desire,’ I could write the book on avoiding it. -

A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams

A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams Copyright Notice ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale Cengage. Gale is a division of Cengage Learning. Gale and Gale Cengage are trademarks used herein under license. For complete copyright information on these eNotes please visit: http://www.enotes.com/streetcar/copyright eNotes: Table of Contents 1. A Streetcar Named Desire: Introduction 2. A Streetcar Named Desire: Summary ® Scenes 1 and 2 Summary ® Scenes 3, 4, 5, 6 Summary ® Scenes 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Summary 3. A Streetcar Named Desire: Tennessee Williams Biography 4. A Streetcar Named Desire: Themes 5. A Streetcar Named Desire: Style 6. A Streetcar Named Desire: Historical Context 7. A Streetcar Named Desire: Critical Overview 8. A Streetcar Named Desire: Character Analysis ® Blanche du Bois ® Stanley Kowalski ® Stella Kowalski ® Other Characters 9. A Streetcar Named Desire: Essays and Criticism ® Sex and Violence in A Streetcar Named Desire ® The Structure of A Streetcar Named Desire ® Theater Review of A Streetcar Named Desire 10. A Streetcar Named Desire: Compare and Contrast 11. A Streetcar Named Desire: Topics for Further Study 12. A Streetcar Named Desire: Media Adaptations 13. A Streetcar Named Desire: What Do I Read Next? 14. A Streetcar Named Desire: Bibliography and Further Reading A Streetcar Named Desire: Introduction A Streetcar Named Desire is the story of an emotionally-charged confrontation between characters embodying the traditional values of the American South and the aggressive, rapidly-changing world of modern America. The play, begun in 1945, went through several changes before reaching its final form. Although the scenario initially concerned an Italian family, to which was later added an Irish brother-in-law, Tennessee Williams changed the characters to two Southern American belles and a Polish American man in order to emphasize the A Streetcar Named Desire 1 clash between cultures and classes in this story of alcoholism, madness and sexual violence. -

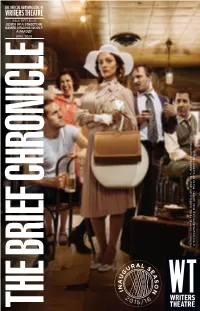

Brief Chronicle

THE OFFICIAL NEWSMAGAZINE OF WRITERS THEATRE ISSUE FIFTY-FOUR DEATH OF A STREETCAR NAMED VIRGINIA WOOLF: A PARODY APRIL 2016 PICTURED: MICHAEL PEREZ, KAREN JANES WODITSCH, JENNIFER ENGSTROM, JENNIFER ENGSTROM, KAREN JANES WODITSCH, PICTURED: MICHAEL PEREZ, TRUGLIA. PHOTO BY SAVERIO JOHN HOOGENAKKER AND MARC GRAPEY. Michael Halberstam ISSUE FIFTY-FOUR: APRIL 2016 Artistic Director Michael Halberstam Kathryn M. Lipuma Artistic Director Executive Director Kathryn M. Lipuma EDITOR Executive Director Chad Peterson Director of Marketing & Communications LEAD WRITER Bobby Kennedy LUX. BRAVE PHOTO BY JOE MAZZA, Literary Manager Dear friends, CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Jaron Bernstein Debra Pucé We seem to have been saying “Welcome” a lot lately. “Welcome to the Inaugural Season in our Director of Institutional Giving Director of Major Gifts & Planned Giving new building.” “Welcome to our new home.” Now it’s “Welcome to the first production in our Kayla Boye Daniel Reinglass intimate Gillian Theatre,” and soon it will be “Welcome to our 25th Anniversary Season!” It serves Marketing & Communications Assistant Advancement Manager as a constant reminder of the immense step that we’ve just taken, and how thrilling the journey Kelsey Chigas Collin Quinn Rice has been and continues to be. We’re delighted to have you with us throughout this experience, and Education Outreach Coordinator Design & Content Coordinator hope that you’re enjoying our new home as much as we are! Krista Damico Nicole Ripley Marketing Manager Director of Education In this edition of The Brief Chronicle, you’ll hear from the author of Death of a Streetcar Named Michael Halberstam Ryan Stanfield Virginia Woolf: A Parody and learn about his inspiration in creating this delicious piece of satire. -

Tennessee Williams's a Streetcar Named Desire

Queering and dequeering the text : Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire Georges-Claude Guilbert To cite this version: Georges-Claude Guilbert. Queering and dequeering the text : Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. Cercles : Revue Pluridisciplinaire du Monde Anglophone, Université de Rouen, 2004. hal- 02149502 HAL Id: hal-02149502 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02149502 Submitted on 6 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cercles 10 (2004) QUEERING AND DEQUEERING THE TEXT Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire GEORGES-CLAUDE GUILBERT Université de Rouen The Dead-Queer Motif Elizabeth Taylor once declared: “Without homosexuals there would be no theater, no Hollywood, […] no Art!”. In the 1940s and 1950s, America was not particularly liberal, to put it mildly, and definitely not “gay-friendly.” However, as Frederick Suppe writes, [The] cultural and artistic contributions of queers were decidedly subversive, countering attempts to smother gays and lesbians into cultural invisibility with films, plays, literature, music and art that revealed and made public a gay sensibility that spoke to queers everywhere even when the plots and vehicles used to deploy that sensibility were disguised as heterosexual. -

Masculinity Studies: the Case of Brando

Arts and Humanities in Higher Education http://ahh.sagepub.com/ Masculinity studies : The case of Brando Samantha Pinto Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 2011 10: 23 DOI: 10.1177/1474022210389575 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ahh.sagepub.com/content/10/1/23 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Arts and Humanities in Higher Education can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ahh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ahh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://ahh.sagepub.com/content/10/1/23.refs.html >> Version of Record - Feb 28, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from ahh.sagepub.com at UNIV OF TEXAS AUSTIN on June 18, 2012 Masculinity studies The case of Brando samantha pinto Georgetown University, USA abstract This reflective article interrogates the role of masculinity studies in the women’s and gender studies’ classroom by looking at the work of American film icon Marlon Brando. Brando and his risky masculinity in the film represents a locale of ‘dangerous desires’ which reveal deep conflict in student perceptions of men, women, and gender. keywords Brando, desire, feminism, gender, masculinity, pedagogy, whiteness Adrienne kennedy, african-american playwright, says of her fascination with Marlon Brando in her memoir-cum-childhood scrapbook, People Who Led to My Plays: His roles seemed to convey themes. In Viva Zapata, a person has to fight and lead. In Streetcar, there is within the world violence, danger. In On the Waterfront, a person must try to attain honor.