Environmental Assessment Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Louisiana's Federal Legislators Senators

List of Louisiana's Federal Legislators Senators Senator Mary Landrieu Senator David Vitter United States Senate United States Senate 724 Hart Senate Office Building 516 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-5824 (202) 224-4623 (202) 224-9735 fax (202) 228-5061 fax http://landrieu.senate.gov http://vitter.senate.gov District Office - Baton Rouge: District Office - Alexandria: Federal Building, Room 326 2230 South MacArthur Drive Suite 4 707 Florida Street Alexandria, LA 71301 Baton Rouge, LA 70801 Phone: 318-448-0169 Phone: 225-389-0395 Fax: 318-448-0189 Fax: 225-389-0660 District Office - Baton Rouge: District Office - Lake Charles: 858 Convention Street Hibernia Tower Baton Rouge, LA 70801 One Lakeshore Drive, Suite 1260 Phone: 225-383-0331 Lake Charles, LA 70629 Fax: 252-383-0952 Phone: 337-436-6650 Fax: 337-439-3762 District Office - Lafayette: 800 Lafayette Street Suite 1200 District Office - New Orleans: Baton Rouge, LA 70808 Hale Boggs Federal Building, Suite 1005 Phone: 337-262-6898 500 Poydras Street Fax: 337-262-6373 New Orleans, LA 70130 Phone: 504-589-2427 District Office - Lake Charles: Fax: 504-589-4023 3221 Ryan Street Suite E Lake Charles, LA 70601 District Office - Shreveport: Phone: 337-436-0453 United States Courthouse Fax: 337-436-3163 300 Fannin Street, Suite 2240 Shreveport, LA 71101 District Office - Metairie: Phone: 318-676-3085 2800 Veterans Boulevard Suite 201 Fax: 318-676-3100 Metairie, LA 70002 Phone: 504-589-2753 Fax: 504-589-2607 District Office - Monroe: 1217 North 19th Street Monroe, LA 71201 Phone: 318-325-8120 Fax: 318-325-9165 District Office - Shreveport: 920 Pierremont Road Suite 113 Shreveport, LA 71106 Phone: 318-861-0437 Fax: 318-861-4865 Representatives Rep. -

Leonard Kancher

\ 4. 4. madesignificant contributions in whohave Recognition ofwomen 3. Opportunities service forpublic forwomen; 2. Nontraditional careers forwomen; 1. Leadership andpublic-policy trainingopportunities forhigh- nontraditional roles and/or public service; and/orpublic nontraditional roles ages13andabove; potential females, Th Nic PO Bo Th University State Nicholls PO Box 2062 National ibo ibodaux, LA 70310 h o d l x Women’s Leadership The Louisiana Center for Women in Government andBusiness inGovernment Women The LouisianaCenterfor Summit on National Women’s Leadership Summit Women’s National at Nicholls State University University NichollsState at SMALL BUSINESS ENTREPRENEURSHIP and promotes NON-TRADITIONAL 6. 6. intellectualproperty forwomen andpolicy initiatives Louisiana’s 5. Internships andopportunities institutionsofhigher forstudentsat OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN across the United States. theUnited States. across and andtheeconomy; business among government, servicepublic andlearn andinteraction abouttherelationship practicalexperience in ofmajor)tohave (regardless education Hosted by Louisiana Center for Women in Government and Business june 28 and 29, 2013 Hilton New Orleans Riverside New Orleans, Louisiana HONORARY CO-CHAIRS Conference registration fee is $150 which includes: Mary Landrieu, US Senator • Continuing Education credits for Professional Development, David Vitter, US Senator Nicholls State University HOST COMMITTEE • General session with Jane Campbell • US Representative Rodney Alexander Breakout sessions with national -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

US Fish & Wildlife Service

U.S. FishU.S &. FishWildlife & Wildlife Service Service Kisatchie Painted Crayfish Arlington, Texas Ecological Services Field Office Kisatchie Painted Crayfish Faxonius maletae During the winter, the mortality rate of crayfish Description increases due to mating stress, starvation, and The Kisatchie painted crayfish predation. Abiotic (Faxonius maletae) is an elusive, factors such as low freshwater crayfish endemic to the dissolved oxygen levels streams of northeast Texas and and temperature Louisiana. It is characterized by an fluctuations can also olive carapace (hard, upper shell) influence crayfish and the red marks on the chelae survival. (claws), legs, and above the eyes. Crayfish, in general, are keystone species that may indicate the health F. maletae Habitat of a watershed, and nearly half of Photo: Steve Shively, USDA Forest Service Little is known about the crayfish species are vulnerable, habitat requirements of the determined that the Kisatchie painted threatened, or endangered. The size of Kisatchie painted crayfish. They were crayfish was absent from 60% of its Kisatchie painted crayfish appears to historically collected in freshwater historical range in Texas. be influenced by water depth. streams with sand, gravel, mud, or silt Individuals found in deep water have in northeast Texas and Louisiana. been documented to reach lengths of Life History However, the Texas habitat was more 101.6 mm, while those found in The Kisatchie painted crayfish is stagnant and muddy than Louisiana. shallow water rarely reach lengths reproductively active in September Kisatchie painted crayfish may prefer over 50.8 mm. and October; unlike other crayfish that streams with varying water depth, reproduce in the spring. -

Biological Evaluation Usda - Forest Service, Kisatchie National Forest Catahoula Ranger District

Catahoula RD – North Gray Creek 2 Aug 19 BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION USDA - FOREST SERVICE, KISATCHIE NATIONAL FOREST CATAHOULA RANGER DISTRICT North Gray Creek I. INTRODUCTION This report documents the findings of the Biological Evaluation (BE) for the proposed silvicultural activities in Compartments 89-93 on the Catahoula Ranger District of the Kisatchie National Forest. It also serves to provide the decision maker with information and determinations of the effects of proposed actions on proposed, endangered, threatened and sensitive (PETS) species and habitats so that the best decisions can be made regarding these species and the proposal. PETS species are species whose viability is most likely to be put at risk from management actions. Through the BE process the proposed management activities were reviewed and their potential effects on PETS species disclosed. Evaluation methods included internal expertise on species' habitat requirements, field surveys, Forest Service inventory and occurrence records, Final Environmental Impact Statement/Revised Land and Resource Management Plan for the Kisatchie National Forest, the recovery plans for the the red- cockaded woodpecker (RCW) and Louisiana pearlshell mussel (LPM) and the draft recovery plan and candidate conservation agreement (CCA) for the Louisisana pine snake (LPS). This biological evaluation was prepared in accordance with Forest Service Handbook 2609.23R and regulations set forth in Section 7 (a)(2) of the Endangered Species Act. A botanical evaluation was done separately to address impacts on sensitive and conservation plants. PURPOSE AND NEED: Differences between current and desired conditions have been identified within the project area. In order to move the project area toward the desired conditions, specific resource management actions were identified and developed. -

2017 Pictorial Roster of Members

2017 PICTORIAL ROSTER OF MEMBERS 2017 Board of Directors 2 Pictorial Roster of Members 3 Alphabetical Listing of Registered Lobbyists 28 Alphabetical Listing by Company 90 Association of Louisiana Lobbyists P.O. Box 854 Baton Rouge, LA 70821 (225) 767-7640 Ask for Jamie Freeman, Account Manager [email protected] LouisianaLobbyists.org 1 2016-2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jody Montelaro John Walters Markey Pierre’ Ryan Ha ynie President Vice-President Secretary/ Immediate Entergy Services Associated Builders Treasurer Past-President and Contractors Southern Strategy Haynie & Group of North Associates Louisiana 2017 PICTORIAL ROSTER OF MEMBERS (as of March 20, 2017) Alisha Duhon Larry Murray Christian Eric Sunstrom Adams & Reese The Picard Group Rhodes The Chesapeake Roedel Parsons Group Drew Tessier David Tatman Union Pacific Executive Director Railroad Association of Louisiana Lobbyists 2 3 Adams, Ainsworth, Albright, Bailey, Lauren Bascle, Arwin Beckstrom, Mark E. Pete Kevin O. Jeffrey W. LA State Medical Society Arwin P. Bascle, LLC Ochsner Health System LA District Attorneys Jones Walker Independent Insurance 6767 Perkins Rd, Ste 100 2224 Eliza Beaumont Ln 880 Commerce Road Association 8555 United Plaza Blvd, Agents of LA Baton Rouge, LA 70808 Baton Rouge, LA 70808 West, Ste. 500 1645 Nicholson Dr Ste. 500 18153 E. Petroleum Dr Cell: (225)235-2865 Cell: (504) 296-4349 New Orleans, LA 70123 Baton Rouge, LA 70802 Baton Rouge, LA 70809 Baton Rouge, LA 70809 [email protected] [email protected] Work: (504) 842-3228 Work:(225) 343-0171 Work: (225) 248-2036 Work: (225) 819-8007 Fax: (504) 842-9123 Fax: (225) 387-0237 Cell: (225) 921-3311 Fax: (225) 819-8027 [email protected] [email protected] Fax: (225) 248-3136 [email protected] kainsworth@ joneswalker.com Allison, Don Ashy, Alton E. -

The Status of the Kisatchie Painted Crayfish (Faxonius Maletae) in Louisiana

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler Biology Theses Biology Spring 3-22-2019 The tS atus of the Kisatchie Painted Crayfish (Faxonius maletae) in Louisiana Jade L.M. McCarley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/biology_grad Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation McCarley, Jade L.M., "The tS atus of the Kisatchie Painted Crayfish (Faxonius maletae) in Louisiana" (2019). Biology Theses. Paper 58. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/1317 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STATUS OF THE KISATCHIE PAINTED CRAYFISH (FAXONIUS MALETAE) IN LOUISIANA by JADE L. M. MCCARLEY A thesis submitted in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Biology Department of Biology Lance R. Williams, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler May 2019 © Copyright Jade L. M. McCarley 2019 All rights reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge Dr. Bob Wagner, Quantitative Ecological Services (QES), Jody Patterson, Sarah Pearce, and the staff at Fort Polk for all of their support throughout this project. I am sincerely grateful for my advisor, Lance Williams for this opportunity. He has guided me through graduate school and has inspired me to continue as a scientist. Thank you, Marsha Williams for your dedication to field sampling and especially for welcoming me into your family while at UT. -

Special Election Dates

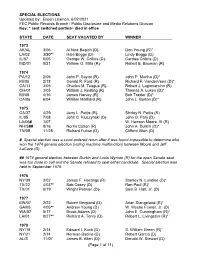

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Membership in the Louisiana House of Representatives

MEMBERSHIP IN THE LOUISIANA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 1812 - 2024 Revised – July 28, 2021 David R. Poynter Legislative Research Library Louisiana House of Representatives 1 2 PREFACE This publication is a result of research largely drawn from Journals of the Louisiana House of Representatives and Annual Reports of the Louisiana Secretary of State. Other information was obtained from the book, A Look at Louisiana's First Century: 1804-1903, by Leroy Willie, and used with the author's permission. The David R. Poynter Legislative Research Library also maintains a database of House of Representatives membership from 1900 to the present at http://drplibrary.legis.la.gov . In addition to the information included in this biographical listing the database includes death dates when known, district numbers, links to resolutions honoring a representative, citations to resolutions prior to their availability on the legislative website, committee membership, and photographs. The database is an ongoing project and more information is included for recent years. Early research reveals that the term county is interchanged with parish in many sources until 1815. In 1805 the Territory of Orleans was divided into counties. By 1807 an act was passed that divided the Orleans Territory into parishes as well. The counties were not abolished by the act. Both terms were used at the same time until 1845, when a new constitution was adopted and the term "parish" was used as the official political subdivision. The legislature was elected every two years until 1880, when a sitting legislature was elected every four years thereafter. (See the chart near the end of this document.) The War of 1812 started in June of 1812 and continued until a peace treaty in December of 1814. -

TAS Program 2018.Pdf

About The Texas Academy of Science History First founded by teachers as the Academy of Science in Texas in 1880, the organization as we know it now emerged around 1929 and included a physicist, a botanist, a mathematician and two biologists as its founding members. Now, TAS publishes a peer-reviewed journal (The Texas Journal of Science since 1949), conducts an annual meeting that highlights research across 17 sections across the sciences, provides substantial funding opportunities for students (~$25,000 awarded annually) and facilitates expert testimony on policy issues related to STEM or science education. TAS membership approaches 600 individuals, with a large portion of the membership as students. Mission As part of its overall mission, the Texas Academy of Science promotes scientific research in Texas colleges and universities, encourages research as a part of student learning and enhances the professional development of its professional and student members. TAS possesses a complex, intriguing and long-standing educational mission. Strategic Planning The Texas Academy of Science (TAS) Board of Directors recently approved a vision for a 5-year Strategic Plan: “to increase the visibility and effectiveness of TAS in promoting strong science in Texas.” As part of that initiative, the Academy seeks to reach out to foundations and organizations that support and benefit the Texas science community. We believe that a number of opportunities exist for strategic partnerships that could bolster the impact of organizations that raise the profile of science in Texas. Our ultimate goal will be to make TAS the premier state academy in the United States; however, this cannot be accomplished without funding from both individuals and corporations. -

Conservation

CONSERVATION ecapod crustaceans in the families Astacidae, recreational and commercial bait fisheries, and serve as a Cambaridae, and Parastacidae, commonly known profitable and popular food resource. Crayfishes often make as crayfishes or crawfishes, are native inhabitants up a large proportion of the biomass produced in aquatic of freshwater ecosystems on every continent systems (Rabeni 1992; Griffith et al. 1994). In streams, sport except Africa and Antarctica. Although nearly worldwide fishes such as sunfishes and basses (family Centrarchidae) in distribution, crayfishes exhibit the highest diversity in may consume up to two-thirds of the annual production of North America north of Mexico with 338 recognized taxa crayfishes, and as such, crayfishes often comprise critical (308 species and 30 subspecies). Mirroring continental pat- food resources for these fishes (Probst et al. 1984; Roell and terns of freshwater fishes (Warren and Burr 1994) and fresh- Orth 1993). Crayfishes also contribute to the maintenance of water mussels (J. D. Williams et al. 1993), the southeastern food webs by processing vegetation and leaf litter (Huryn United States harbors the highest number of crayfish species. and Wallace 1987; Griffith et al. 1994), which increases avail- Crayfishes are a significant component of aquatic ecosys- ability of nutrients and organic matter to other organisms. tems. They facilitate important ecological processes, sustain In some rivers, bait fisheries for crayfishes constitute an Christopher A. Taylor and Melvin L. Warren, Jr. are cochairs of the Crayfish Subcommittee of the AFS Endangered Species Committee. They can be contacted at the Illinois Natural History Survey, Center for Biodiversity, 607 E. Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820, and U.S. -

110Th Congress 113

LOUISIANA 110th Congress 113 Chief of Staff.—Casey O’Shea. FAX: 226–3944 Legislative Director.—Jacob Roche. Scheduler.—Jody Comeaux. 828 S. Irma Boulevard, 212A, Gonzales, LA 70737 .................................................. (225) 621–8490 District Director.—Barney Arceneaux. 423 Lafayette Street, Suite 107, Houma, LA 70360 ................................................... (985) 876–3033 210 East Main Street, New Iberia, LA 70560 ............................................................. (337) 367–8231 8201 West Judge Perez Drive, Chalmette, LA 70043 ................................................. (504) 271–1707 Parishes: ASCENSION (part), ASSUMPTION, IBERIA, JEFFERSON (part), LAFOURCHE, PLAQUEMINES, ST. BERNARD, ST. CHARLES (part), ST. JAMES, ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST, ST. MARTIN, ST. MARY, TERREBONNE. Population (2000), 638,322. ZIP Codes: 70030–32, 70036–41, 70043–44, 70047, 70049–52, 70056–58, 70067–72, 70075–76, 70078–87, 70090–92, 70301– 02, 70310, 70339–46, 70353–54, 70356–61, 70363–64, 70371–75, 70377, 70380–81, 70390–95, 70397, 70512–14, 70517– 19, 70521–23, 70528, 70538, 70540, 70544, 70552, 70560, 70562–63, 70569, 70582, 70592, 70723, 70725, 70734, 70737, 70743, 70763, 70778, 70792 *** FOURTH DISTRICT JIM MCCRERY, Republican, of Shreveport, LA; born in Shreveport, September 18, 1949; education: graduated Leesville High, Louisiana, 1967; B.A., Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, 1971; J.D., Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 1975; attorney; admitted to the Louisiana bar in 1975 and commenced practice in Leesville,