THE NEWGATE CALENDAR

Edited by Donal Ó Danachair

Volume 6

Published by the Ex-classics Project, 2009 http://www.exclassics.com

Public Domain

-1-

THE NEWGATE CALENDAR

The Gibbets

-2-

VOLUME 6

CONTENTS

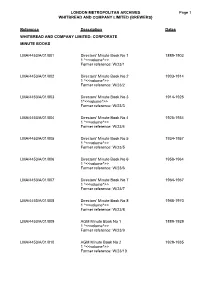

DAVID OWEN Tried and executed for a diabolical attempt to murder his sister, her

husband, and their servant maid, 4th April, 1818 .........................................................6 MARY STONE............................................................................................................11 GEORGE CHENNEL AND J. CHALCRAFT............................................................14 CHARLES HUSSEY...................................................................................................30 ROBERT JOHNSTON................................................................................................31 SAMUEL SIBLEY; MARIA CATHERINE SIBLEY; SAMUEL JONES; his son; THOMAS JONES; JOHN ANGEL; THOMAS SMITH; JAMES DODD and EDWARD SLATER....................................................................................................33

ROBERT DEAN..........................................................................................................36 HENRY STENT ..........................................................................................................40 PEI................................................................................................................................54 JOHN SCANLAN and STEPHEN SULLIVAN .........................................................59 MRS MARY RIDDING ..............................................................................................62 SIR FRANCIS BURDETT..........................................................................................64 ARTHUR THISTLEWOOD, JAMES INGS, JOHN THOMAS BRUNT, RICHARD TIDD AND WILLIAM DAVIDSON..........................................................................67

PHILIP HAINES AND MARY CLARKE..................................................................74 JOHN SMITH..............................................................................................................80 DANIEL DOODY, JOHN CUSSEN, alias WALSH, JAMES LEAHY, MAURICE LEAHY, WILLIAM DOODY, DAVID LEAHY, DANIEL RIEDY, WILLIAM COSTELLO, AND WALTER FITZMAURICE, alias CAPTAIN ROCK .................83

PHILIP STOFFEL AND CHARLES KEPPEL...........................................................86 HENRY FAUNTLEROY............................................................................................88 CORNELIUS WOOD..................................................................................................90 EDWARD HARRIS, alias KIDDY HARRIS .............................................................94 GEORGE ALEXANDER WOOD AND ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH ....101 EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD, WILLIAM WAKEFIELD AND FRANCES WAKEFIELD ............................................................................................................102

WILLIAM CORDER.................................................................................................108 JOSEPH HUNTON ...................................................................................................118 ESTHER HIBNER THE ELDER, ESTHER HIBNER THE YOUNGER, AND ANN ROBINSON ...............................................................................................................123 WILLIAM BANKS ...................................................................................................126 WILLIAM BURKE ...................................................................................................129 CAPTAIN WILLIAM MOIR....................................................................................146 JOHN SMITH, alias WILLIAM SAPWELL ............................................................149 JOHN ST JOHN LONG ............................................................................................153 JOHN TAYLOR AND THOMAS MARTIN............................................................156

-3-

THE NEWGATE CALENDAR

JOSEPH PLANT STEVENS.....................................................................................158 LEWIS LEWIS, RICHARD LEWIS, DAVID HUGHES, THOMAS VAUGHAN, DAVID THOMAS, AND OTHERS..........................................................................160 JOHN AMY BIRD BELL .........................................................................................167 JOHN BISHOP AND THOMAS WILLIAMS..........................................................169 JOHN HOLLOWAY .................................................................................................175 HENRY MACNAMARA..........................................................................................177 DENNIS COLLINS...................................................................................................179 JONATHAN SMITHERS .........................................................................................182 JAMES COOK...........................................................................................................185 WILLIAM JOHNSON...............................................................................................188 JOB COX...................................................................................................................190 GEORGE FURSEY...................................................................................................192 JAMES LOVELACE and others ...............................................................................196 PATRICK CARROLL...............................................................................................199 ROBERT SALMON..................................................................................................200 JOHN MINTER HART .............................................................................................201 JAMES GREENACRE..............................................................................................203 THOMAS MEARS AND OTHERS..........................................................................206 FRANCIS LIONEL ELIOT, EDWARD DELVES BROUGHTON, JOHN YOUNG AND HENRY WEBBER ..........................................................................................213 FRANCIS HASTINGS MEDHURST.......................................................................215 GEORGE CANT .......................................................................................................216 WILLIAM JOHN MARCHANT...............................................................................221 ROBERT TAYLOR...................................................................................................222 FRANCOIS BENJAMIN COURVOISIER...............................................................227 EDWARD OXFORD.................................................................................................232 THE EARL OF CARDIGAN....................................................................................239 WILLIAM STEVENSON .........................................................................................243 JAMES INGLETT.....................................................................................................245 HUFFEY WHITE AND RICHARD KENDALL......................................................247 RICHARD CORDUY................................................................................................250 PRIVATE HALES.....................................................................................................251 MARTHA DAVIS.....................................................................................................252 JOHN ROBINSON....................................................................................................253 LEVI MORTGEN AND JOSEPH LUPPA...............................................................255 ELIZABETH MIDDLETON.....................................................................................256 JOHN MUCKETT.....................................................................................................257 PATRICK M'DONALD ............................................................................................258 JAMES BULLOCK...................................................................................................259 FREDERICK SMITH ALIAS HENRY ST JOHN ...................................................261 SAMUEL OLIVER ...................................................................................................262

-4-

VOLUME 6

THOMAS WHITE AND WALTER WYATT..........................................................263 APPENDIX I .............................................................................................................264 APPENDIX II............................................................................................................266 APPENDIX III...........................................................................................................269 APPENDIX IV...........................................................................................................272 APPENDIX V............................................................................................................273 APPENDIX VI...........................................................................................................275 APPENDIX VII. ........................................................................................................281 APPENDIX VIII........................................................................................................284 APPENDIX IX...........................................................................................................287 APPENDIX X............................................................................................................293 APPENDIX XI...........................................................................................................296 APPENDIX XII .........................................................................................................326 APPENDIX XIII........................................................................................................333 APPENDIX XIV........................................................................................................343

APPENDIX Voluntary punishment of Gentoo widows on the death of their husbands

....................................................................................................................................357

APPENDIX Trial by ordeal of the Hindoos in the Eas t............................................360

APPENDIX Chinese punishment s.............................................................................361

APPENDIX Turkish Punishments inflicted on knavish butchers and bakers. ..........363

APPENDIX Benefit of clergy. ...................................................................................366 CONCLUDING NOTE .............................................................................................368

-5-

THE NEWGATE CALENDAR

DAVID OWEN

Tried and executed for a diabolical attempt to murder his sister, her husband, and their servant maid, 4th April, 1818

THE attempt of DAVID OWEN to murder his sister, her husband, and their maid servant, is one of those instances of desperate depravity which reflect disgrace, not merely on the age, but on human nature itself. On the 26th September, 1817, about one o'clock at noon, this man, who was a cow-keeper, came to town from Edmonton, and proceeded to the house of his brother-in-law, also a cow-keeper, in Gibraltar-row, St. George's-fields. After knocking at the door, he was admitted by the maid servant, who called out to her master and mistress that Mr Owen was there; and Jones coming forward to meet him, the execution of his diabolical purpose commenced. He first attacked the man Jones, whom he wounded dreadfully in the belly and the hand, so far as for some seconds to deprive him of sense and motion. He then flew at Mrs Jones, his own sister, and inflicted upon her several shocking wounds: he stabbed her in the forehead, cut her severely, though not dangerously, between two of her ribs, and having thrust his knife in her mouth, drew it clean through the face to the ear, lacerating her tongue, and laying her cheek completely open. The ruffian last struck at the servant girl, whom he seriously cut in the face and one of her hands, besides dividing the main artery of her arm.

The poor wretches, though faint and almost insensible with terror and loss of blood, contrived to make their way into the street, where they were immediately observed by their neighbours, and were carried into the adjoining houses till medical assistance could be procured. In the meantime, the assassin had fastened the door of Jones's house, and with loud imprecations threatened to destroy any person who should dare to approach him. This threat, together with the impression of the horrible scene before them, and the circumstance of Owen (a remarkably large and powerful man) being armed with two knives, completely deterred the multitude, though soon consisting of many hundreds, from attempting to enter the house. Police-officers, however, were sent for, and on their arrival, and after the interval of nearly an hour, it was determined to break into the house and seize the desperate villain. For this purpose a great number of persons armed with pokers and crow-bars, some with ladders at the windows, and some on the ground, made a simultaneous attack on the house, and bursting it open above and below, rushed in with great force.

They found Owen on the first landing place, standing with an air of defiance, and whetting his knives one upon the other, as if for the purpose of rendering them more effectually murderous. One of the officers, however, without a moment's delay, struck him a violent blow with a crow-bar on the head, which knocked off his hat and staggered him; and another instantly took advantage of his tottering, seized one of his legs, and threw him on the ground. Still the ruffian was able to resist, which he did so obstinately, that the officers were compelled to beat and even wound him severely about the face and body, before he was subdued to a state of acquiescence. During the scuffle within, thousands of the multitude, indignant and horrified at the dreadful deed of blood which had been perpetrated, assembled outside of the house, with arms of various kinds, in order to prevent the possibility of his escape.

-6-

VOLUME 6

When overcome by the superior force of his opponents, he exhibited all the rage of a madman, and could only be moved by main force; his arms and legs being confined by strong ropes. Holmes, the most active of the officers, then sent for a hackney-coach, and had his prisoner lifted in and driven to Union-hall, where he underwent a partial examination before Mr Evance, the Sitting Magistrate.

Nothing could exceed in horror the terrific and bloody spectacle which he exhibited on this occasion; he was covered both with his own blood and that of his unhappy victims, from his head to his feet, and had more the appearance of a demon than of a human being. On being placed at the bar, he fixed his eyes upon a Jew attorney, named Cohen, and gnashing his teeth, he exclaimed, "You have been the cause of this!" Upon the evidence of Holmes, he was committed to Horsemonger-lane gaol, whither he was followed by some hundreds of persons, who overwhelmed him with their execrations. He had received a severe cut on the head, and one of his fingers was nearly severed from his hand; his legs and arms were also severely bruised.

As to the motive of this savage barbarity, it appeared, that some years back.

Jones and his wife brought up from Wales two lads, the sons of Owen, whom they treated as their own; educating and supporting them in the best manner their circumstances would permit. The prisoner, Owen, in the mean time, carried on the business of a publican, at Edmonton, and having been guilty of some act of unkindness towards his brother-in-law, Jones, the latter thought proper to commence an action at law against him for the board and education of his two sons. In this action he employed the Jew attorney, Cohen, whom Owen addressed with so much bitterness on his entering the office. Cohen lost no time in furthering the views of his client, and proceeded without delay to serve a copy of a writ on Owen, at his house at Edmonton. The effect of this proceeding was so powerful upon Mrs Owen, that she actually died two days subsequent to the writ having been served; and to this event, melancholy as it certainly was, may perhaps be traced that hatred which at last led to the dreadful scene we have been describing. The action was, in the meantime pursued, but upon being brought into court, a reference was recommended and adopted, and the facts of the case were submitted to the arbitration of Mr Barrow and Mr Reynolds.

It appeared that a set-off was made by Owen against Jones's bill, in which he charged the latter for the work and labour of his sons, during the number of years they had been living with him; and as it appeared that the boys had been very generally employed in assisting Jones in his business of a cow-keeper, this set-off was admitted, and an award actually made in favour of Owen, over and above the sum demanded by Jones, of £100. The effect of this award was to drive Jones and his wife from the possession of some premises which belonged to Owen, situate at Newington. These premises Owen let to other tenants; and on his coming up to look after his rent, to his surprise and vexation, he found the house deserted, and the late occupants gone. It turned out, that the tenants had been detected in carrying on an unentered soap-work, and had found it convenient to fly, without the usual notice to the landlord.

The effect of this discovery on the mind of Owen was such, added to the recollection that his law-suit with his brother-in-law was the original cause, not alone of his present loss, but of his wife's death, as to produce a temporary fit of phrenzy, during which he determined to he fully avenged by the death of him whom he conceived to be the original offender. He immediately went to a house in the

-7-

THE NEWGATE CALENDAR neighbourhood, where he dined and having increased his passion by the use of spirituous liquors he set out on his atrocious expedition, in which he succeeded in the melancholy manner we have already detailed.

The parties were all Welsh; Jones and his wife about forty years of age; the servant girl about twenty; Owen between forty-five and fifty, a man of remarkably formidable size and strength. The age of the eldest son was about eleven; both this lad and his brother had always preferred the society of their uncle and aunt to that of their father; and upon the elder one devolved the whole management of his uncle's business, consisting of an extended milk-walk. The servant girl, Mary Barry, had lived with them from her infancy, and was sincerely attached to them, She was a witness for Jones before the arbitrators, a circumstance which may perhaps account for the enmity of Owen towards her.

While Owen was being removed to Union-hall, surgical aid was procured for the wounded, and the opinion given by Mr Dixon, surgeon of Newington, was, that he considered the husband likely to die; the wife dreadfully, though not mortally, wounded; and the girl, though very seriously hurt, likely to recover. The man and the servant were, at the recommendation of the surgeon, taken to one of the hospitals, and Mrs Jones was carried back to her own house.

Jones's house exhibited a most desolate appearance, from the means that were taken to apprehend the assassin. The sashes at the back of the house had been forced out; and from the numbers of persons who pressed upstairs together, the bannisters were completely demolished.

In consequence of the weak and doubtful state in which the victims of Owen's sanguinary attack remained, no further inquiry into the particulars took place till the 10th of October following; and, indeed, the wretched prisoner himself had suffered so much from the severe treatment he had necessarily received in his capture, that he also was unfit to be removed at an earlier period.

Although it was not positively known that the prisoner would be examined on that day, yet several hours previous to the examination an amazing number of persons assembled, and the business of the office suffered considerable interruption. The Magistrates therefore thought it expedient to remove the prisoner into a private room for examination.

At one o'clock Mr Jones and Mary Barry arrived in a hackney-coach from St.

Thomas's Hospital, under the care of a surgeon and two nurses; they were so weak as scarcely to be able to stand. At two the prisoner was brought into the room and confronted with Jones and the servant; the latter fainted as soon as she saw him, and it was with difficulty that Mr Jones was roused to sensibility. When he recovered, he exclaimed, "God! I thought I saw him with a knife in his hand." The magistrate ordered the prisoner to be taken out of the room, as his presence so much agitated the prosecutors. About two Mrs Jones arrived in a hackney-coach, also extremely weak, and the magistrates proceeded to hear evidence.

Mary Barry, the servant, stated, "On the 26th of September last, a little after one o'clock in the afternoon, I was at home with my master and mistress, and heard a knock at the door; I opened it, and saw the prisoner; without saying a word he forced himself in; my master was in the back room; I called out, "Mr Owen is here!" and my

-8-

VOLUME 6 master then came out of the back room into the passage, where he met the prisoner. The prisoner immediately took from under his coat a large pointed carving-knife, and without speaking made a blow at my master, who lifted his hand to defend himself, and prisoner cut and struck him dreadfully on the hand. My mistress then came out, and she and I attempted to save my master, and take away the knife. I got hold of it, and he drew it through my hand, and cut me very much, and then he began cutting and slashing away at random, and cut us all three; he cut me on the arm, stabbed me in the neck, and wounded me in the forehead. I then ran out, and called for assistance, and came back again, and found my master lying on the floor in the back room, bleeding very much, and the prisoner lying over him, with a knife under my master's clothes, and apparently sticking in his side; when I returned to the house, a young man returned with me, and he assisted, and we held Owen's arms and got the knife from him, I was then taken by some persons to the hospital.

Mr Jones deposed to the same effect, and added, that the cut he received across the hand in the passage disabled him from offering much defence; and he soon became insensible; when he recovered, he found himself dreadfully cut in the neck, and part of his left ear off, He formerly had a law suit with prisoner, but had not spoken to him since August, 1816.

Mrs Jones stated, that during the struggle between them all in the passage, she heard prisoner say, "You wretches, I'll kill you all," She received several cuts about the head and face, and a stab in the side: saw the prisoner attempt to stab her husband in the side; then became senseless, having bled excessively.