Temple Entry Movements in Kerala- a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

Extrimist Movement in Kerala During the Struggle for Responsible Government

Vol. 5 No. 4 April 2018 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 Impact Factor: 3.025 EXTRIMIST MOVEMENT IN KERALA DURING THE STRUGGLE FOR RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT Article Particulars: Received: 13.03.2018 Accepted: 31.03.2018 Published: 28.04.2018 R.T. ANJANA Research Scholar of History, University of Kerala, India Abstract Modern Travancore witnessed strong protests for civic amenities and representation in legislatures through the Civic Rights movement and Abstention movement during 1920s and early part of 1930s. Government was forced to concede reforms of far reaching nature by which representations were given to many communities in the election of 1937 and for recruitment a public service commission was constituted. But the 1937 election and the constitution of the Public Service Commission did not solve the question of adequate representation. A new struggle was started for the attainment of responsible government in Travancore which was even though led in peaceful means in the beginning, assumed extremist nature with the involvement of youthful section of the society. The participants of the struggle from the beginning to end directed their energies against a single individual, the Travancore Dewan Sir. C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer who has been considered as an autocrat and a blood thirsty tyrant On the other side the policies of the Dewan intensified the issues rather than solving it. His policy was dividing and rule, using the internal social divisions existed in Travancore to his own advantage. Keywords: civic amenities, Civic Rights, Public Service Commission, Travancore, Civil Liberties Union, State Congress In Travancore the demand for responsible government was not a new development. -

Download Article

ISSN: 2393-8900 Impact Factor : 2.7825(UIF) Volume - 7 | Issue - 2 | Oct - 2020 Historicity Research Journal ________________________________________________________________________________________ EVOLUTION OF MODERN JUDICIAL SYSTEM AND JUDICIAL MANAGEMENT IN TRAVANCORE KINGDOM Dr. S. Pushpalatha1 and Mrs. B.Amutha2 1Assistant Professor & Head (i/c), Department of History, DDE, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai . 2(Reg. No: P5105) Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of History, DDE, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai. ABSTRACT In the history of Travancore Kingdom, there had been a series of changes in judicial system that led to the development of current system of judiciary. During the reign of Marthanda Varma, criminal disputes were disposed in front of the King or Dewan in Padmanabhapuram Palace while petty cases were disposed by local landlords. Karthika Thirunal Rama Varma had empowered the Manikarens, Adhikaries and Proverthikars to settle the disputes in administrative divisions. In the reign of Gowri Lakshmi Bai (1791– 1814), District Courts at Padmanabhapuram, Mavelikara, Trivandrum, Vaikam and Alwaye were established in 1811 and these courts had two judges from Nair or Christian community and a Brahmin Sastri and the ancient Hindu Law was followed in the courts. In addition, a Huzhur court was also established to hear the disputes of Government servants. In 1831 C.E., Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma established Munsiff’s courts for disposal of petty civil cases and police cases, for which a munsiff from the British India was appointed in each court. One year after that, Zilla courts were established in each district and a code of regulations was framed in the British style for hearing the cases in 1834. -

UNIVERSITY of KERALA No.Ad.H/30652/2017/1 N O T I F I C a T I O N Applications Are Invited from Qualified Candidates for Appoint

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA No.Ad.H/30652/2017/1 N O T I F I C A T I O N Applications are invited from qualified candidates for appointment to the posts of Assistant Professor in the following Teaching Departments of the University in the scale of pay of Rs. 15600- 39100 (AGP Rs.6000/-) (Pre revised). Appointments to the posts will be made in accordance with Section (6) Sub Section (2) of Chapter II of the Kerala University Act,1974, UGC Regulations 2010 and amendments made thereon. The turn of appointment as per the principles of rotation is given against each post. Sl. No. Department No. of Turn vacancies 1. Department of Aquatic Biology &Fisheries 1 Muslim 2. Department of Arabic 1 Open 3. Department of Biochemistry 2 OBC Open 4. Department of Commerce 1 Open 5. Department of Communication & Journalism 1 Open 6. Department of Geology 1 SC 7. Department of German 2 Muslim Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 8. Department of Hindi 1 Open 9. Department of Islamic Studies 1 SIUC Nadar 10. Department of Law 1 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya SC 11. Department of Library & Information Science 3 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya Hearing Impaired 12. Department of Linguistics 1 Open 13. Department of Malayalam 1 Open 14. Department of Mathematics 3 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya Open Open 15. Department of Philosophy 1 Open 16. Department of Physics 1 Ezhava/Billava/Thiyya 17. Department of Political Science 2 Open Open 18. Department of Psychology 1 OBC 19. Department of Russian 1 Open 20. Department of Sanskrit 2 Muslim Viswakarma 21. Department of Statistics 2 SC Open 22. -

Reportable in the Supreme Court of India Civil

Civil Appeal No. 2732 of 2020 (arising out of SLP(C)No.11295 of 2011) etc. Sri Marthanda Varma (D) Thr. LRs. & Anr. vs. State of Kerala and ors. 1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE/CIVIL ORIGINAL/INHERENT JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO.2732 OF 2020 [Arising Out of Special Leave Petition (C) No.11295 of 2011] SRI MARTHANDA VARMA (D) THR. LRs. & ANR. …Appellants VERSUS STATE OF KERALA & ORS. …Respondents WITH CIVIL APPEAL NO. 2733 OF 2020 [Arising Out of Special Leave Petition (C) No.12361 of 2011] AND WRIT PETITION(C) No.518 OF 2011 AND CONMT. PET.(C) No.493 OF 2019 IN SLP(C) No.12361 OF 2011 Civil Appeal No. 2732 of 2020 (arising out of SLP(C)No.11295 of 2011) etc. Sri Marthanda Varma (D) Thr. LRs. & Anr. vs. State of Kerala and ors. 2 J U D G M E N T Uday Umesh Lalit, J. 1. Leave granted in Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.11295 of 2011 and Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.12361 of 2011. 2. Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma who as Ruler of Covenanting State of Travancore had entered into a Covenant in May 1949 with the Government of India leading to the formation of the United State of Travancore and Cochin, died on 19.07.1991. His younger brother Uthradam Thirunal Marthanda Varma and the Executive Officer of Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Temple’) as appellants 1 and 2 respectively have filed these appeals challenging the judgment and order dated 31.01.2011 passed by the High Court1 in Writ Petition (Civil) No.36487 of 2009 and in Writ Petition (Civil) No.4256 of 2010. -

![Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3132/temple-entry-movement-for-depressed-class-in-south-travancore-kanyakumari-prathika-703132.webp)

Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika

Prathika. S al. International Journal of Institutional & Industrial Research ISSN: 2456-1274, Vol. 3, Issue 1, Jan-April 2018, pp.4-7 Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika. S Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of History and Research Centre, S.T. Hindu College, Nagercoil 629002. Abstract: The four Tamil speaking taluks of Kanyakumari Dist viz;Agasteeswaram, Thovalai, Kalkulam and Vilavancode consisted the erst while South Tavancore. Among the various religions, Hinduism is the predominant one constituting about two third of the total population. The important Hindu temples found in Kanyakumari District are at Kanyakumari, Suchindrum, Kumarakoil,Nagercoil, Thiruvattar and Padmanabhapuram. The village God like Madan,Isakki, Sasta are worshipped by the Hindus. The people of South Travancore segregated and lived on the basis of caste. The whole population could be classified as Avarnas or Caste Hindus and Savarnas or non-caste people. The Savarnas such as Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras who enjoyed special powers and privileges of wealth constituted the higher castes. The Avarnas viz the Nadars, Ezhavas, Mukkuvas, Sambavars, Pulayas and numerous hill tribes were considered as the polluting castes and were looked down on and had to perform various services for the Savarnas . Avarnas were not allowed in public places, temples, and the temple roads also. Low caste people or Avarnas were considered as untouchable people. Untouchability, one of the major debilities prevailed among the lower order of the society in South Travancore caused an indelible impact on the society. Keywords: Temple Entry Movement, Depressed Class, Kanyakumari reformers against that oppressive activities. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

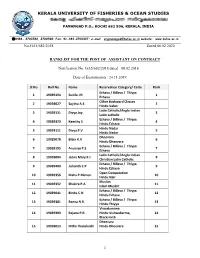

Ranklist for the Post of Assistant on Contract

KERALA UNIVERSITY OF FISHERIES & OCEAN STUDIES PANANGAD P.O., KOCHI 682 506, KERALA, INDIA 0484- 2703782, 2700598; Fax: 91-484-2700337; e-mail: [email protected] website: www.kufos.ac.in No.GA5/682/2018 Dated,06.02.2020 RANKLIST FOR THE POST OF ASSISTANT ON CONTRACT Notification No. GA5/682/2018 dated 08.02.2018 Date of Examination : 24.11.2019 Sl No Roll No Name Reservation Category/ Caste Rank Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 1 19039194 Sunila .M 1 Ezhava Other Backward Classes 2 19039027 Sajitha A.S 2 Hindu Valan Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 3 19039131 Divya Joy 3 Latin catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 4 19039323 Keerthy S 4 Hindu Ezhava Hindu Nadar 5 19039111 Divya P.V 5 Hindu Nadar Dheevara 6 19039078 Bibin K.V 6 Hindu Dheevara Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 7 19039195 Anusree P.S 7 Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 8 19039084 Jeena Mary K J 8 Christian Latin Catholic Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 9 19039403 Jishanth C.P 9 Hindu Ezhava Open Competetion 10 19039356 Nisha P.Menon 10 Hindu Nair Muslim 11 19039352 Shakira P.A. 11 Islam Muslim Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 12 19039041 Bindu.C.N 12 HIndu Ezhava Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 13 19039381 Beena N.K. 13 Hindu Thiyya Viswakarama 14 19039383 Rejana P.R. Hindu Vishwakarma, 14 Blacksmith Dheevara 15 19039013 Hitha Thanckachi Hindu Dheevara 15 1 16 Amrutha Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 16 19039336 Sundaram Hindu Ezhava Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 17 19039114 Mary Ashritha 17 Latin Catholic Latin Catholic/Anglo Indian 18 19039120 Basil Antony K.J 18 Latin Catholic Dheevara 19 19039166 Thushara M.V 19 Deevara Sreelakshmi K Open Competetion 20 19039329 20 Nair Nair Ezhava / Billava / Thiyya 21 19039373 Dileep P.R. -

FATHIMA MEMORIAL TRAINING COLLEGE, PALLIMUKKU, KOLLAM - 10 B.Ed 2019-2021 (English / General List)

FATHIMA MEMORIAL TRAINING COLLEGE, PALLIMUKKU, KOLLAM - 10 B.Ed 2019-2021 (English / General List) Sl.No Name Community Index Marks Rank Remarks 1 SHERINA S Muslim 855 1 Allotted 2 ANJALI G R General 827 2 Allotted 3 REJI R LC 815 3 Allotted 4 ARDHANA T A Ezhava 807 4 Allotted 5 KRISHNAJA KJ General 807 5 Allotted 6 ANN PAUL LC 800 6 Ch-1 7 ANEETA DAS LC 799 7 Ch-2 8 ANAGHA G General 797 8 Ch-3 9 SANAYA H NAZAR Muslim 795 9 Ch-4 10 RESHMA MOHAN General 793 10 Ch-5 11 PAVITHRA PRASAD General 790 11 Ch-6 12 SETHULEKSHMI R S General 783 12 Ch-7 13 ASWATHY S KUMAR General 777 13 Ch-8 14 SNEHA MARY ABRAHAM General 772 14 Ch-9 15 MEERA M General 771 15 Ch-10 16 ARCHA T S General 771 16 Ch-11 17 LEKSHMI A General 770 17 Ch-12 18 SARANYA KRISHNAN S General 770 18 Ch-13 19 AYISHA A Muslim 765 19 Ch-14 20 AGNES A LC 761 20 Ch-15 21 ARCHANA ANIL General 758 21 Ch-16 22 ANJALI ANAND OBH 757 22 Ch-17 23 FATHIMA S Muslim 757 23 Ch-18 24 VAISHNAVI R K General 756 24 Ch-19 25 DEVI PRAKASH General 754 25 Ch-20 26 ARDRA H S Ezhava 753 26 Ch-21 27 NISHA FRANK F LC 750 27 Ch-22 28 SWATHI KRISHNA L General 747 28 Ch-23 29 DHANALEKSHMI P General 747 29 Ch-24 30 SUMAYYA SHERIEF Muslim 742 30 Ch-25 31 STEFFY PETER LC 737 31 Ch-26 32 AJMA SUHARA Muslim 734 32 Ch-27 33 NADIYA S NOUSHAD Muslim 730 33 Ch-28 34 SARAH PAUL LC 729 34 Ch-29 35 MITHA MOHAN L Ezhava 725 35 Ch-30 36 SELIN SAM General 721 36 Ch-31 37 SNEHA M R Ezhava 717 37 Ch-32 38 AKSHARA U S General 712 38 Ch-33 39 APSARA RANI M General 710 39 Ch-34 40 THASLEENA SHAJAHAN Muslim 704 40 Ch-35 41 MAHIMADEVI S Ezhava 703 41 Ch-36 Important: Complaints related to Index marks & reservation claims will not be accepted under any circumstances, after the stipulated time. -

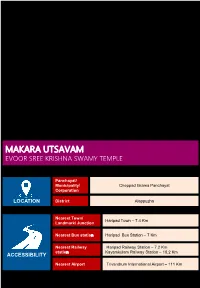

Makara Utsavam Evoor Sree Krishna Swamy Temple

MAKARA UTSAVAM EVOOR SREE KRISHNA SWAMY TEMPLE Panchayat/ Municipality/ Cheppad Grama Panchayat Corporation LOCATION District Alappuzha Nearest Town/ Haripad Town – 7.4 Km Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus station Haripad Bus Station – 7 Km Nearest Railway Haripad Railway Station – 7.2 Km station Kayamkulam Railway Station – 10.2 Km ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Trivandrum International Airport – 111 Km Evoor Sree Krishna Swamy Temple Cheppad Railway Station Road Cheppad – 690507 Contact: Cheppad Grama Panchayat CONTACT Phone: +91-479-2412264 Website: www.evoortemple.org DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME January –February (Makaram); Annual 10 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) Evoor Sreekrishna Swami Temple, also known as Onattukara's Guruvayoor is one of the major Krishna temples in Kerala. It is said to have originated thousands of years ago following Khandava Dahanam. The temple in its current form was built by Moolam Thirunal. The deity of the Lord at at Evoor is the unique Prayoga Chakra Prathishta. It is presented in the four armed Vishnu form with Panchajanya Shankha, Sudarshana Chakra and butter in three hands and the fourth arm held on hip. Raktha- pushpanjali is a special offering at the temple which is unavailable in Vishnu temples elsewhere. The Makara Utsavam starts with the hoisting of the Garuda printed flag and following various rituals and cultural events is pulled down after the Aarattu ceremony as the Lord proceeds for Pallikkuruppu (Holy Sleep). Local RELEVANCE- NO. OF PEOPLE Over 50,000 (Local / National / International) PARTICIPATED EVENTS/PROGRAMS DESCRIPTION (How festival is celebrated) Evoor festival lasts for ten days. The temple and its Flag Hoisting premises are decked up with arches, festoons and Utsavabali decorated with lights, plantain trunks and bunches of Sreebhoothabali coconut and areca nuts. -

Impact of Vaikom and Suchidram Satyagrahas in Travancore- an Historical Overview

IMPACT OF VAIKOM AND SUCHIDRAM SATYAGRAHAS IN TRAVANCORE- AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW Dr. PRAVEEN. O.K Assistant professor, Department of History, SREE KERALA VARMA COLLE, THRISSUR, KERALA, INDIA. ABSTRACT The chief social evil in Travancore, as elsewhere in India, was caste. Though the traditional caste system was not in vogue in Travancore, the Brahmins held the highest place in society. And owners of all land in the country they depended upon the Nairs for the proper management of of the land. The Nairs grew into a warrior class protecting the interests of the Brahmins to form the upper class. The Ezhavas or Tiyas, the Nadars, the pulayas and the parayas were the low caste. These low castes were subjected to glaring disabilities on account of the peculiar social customs which were very strictly followed in Travancore. The treatment which the untouchables received at the hands of the caste Hindus from time immemorial was unsympathetic and even inhuman. Broadly speaking the people of Travancore divided into Avarnas and Savarnas. The avarnas were low castes such as the Adidravidians, Alvans, Aryans, Baratars, Chakaravars, Ezhavas, Kaniyans, Kuravans, Nadars, panas, pulayas, parayas, velan, vedann etc. KEY WORDS: TRAVANCORE, SATYAGRAHA, TEMPLE, VAIKOM SATYAGRHA, SUCHIDRAM SATYAGRHA, TEMPLE ENTRY PROCLAMATION INTRODUCTION They were strictly prohibited from entering into the temples and using public wells, tanks and chatrams (rest houses). Equal opportunity of education and employment was denied to the Avarnas. Unapprochability was also very severe in Travancore. Francis Day says that, Ilava (Ezhava) must keep 36 paces from Brahmin and 12 from a Nayar while a Kaniyan would pollute a Nambudiri Brahmin at 24 ft., 96 paces as the4 distance for a Pulayan from Nair. -

Cabot Sanmar's Fumed Silica Expansion At

1 The Sanmar Group 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. Tel.: + 91 44 2812 8500 Fax.: + 91 44 2811 1902 Sanmar Holdings Ltd Sanmar Consolidations Ltd Chemplast Sanmar Ltd Sanmar Shipping Ltd TCI Sanmar Chemicals S.A.E. Cabot Sanmar Ltd Sanmar Speciality Chemicals Ltd Sanmar Engineering Technologies Ltd - Products Divn. Flowserve Sanmar Ltd BS&B Safety Systems (India) Ltd Xomox Sanmar Ltd Xomox Valves Divn. Pacific Valves Divn. Pentair Sanmar Ltd - Steel Castings Divn. Sanmar Foundries Ltd Matrix Metals LLC 2 In this issue... 4 10 13 The KS Narayanan Oration National Safety Council 2017 recognises Sanmar for 19 safety management 4 Deepak Parekh in conversation with Shekhar practices Gupta The Tenth Annual India Chemplast Sanmar meets Chemical Industry Outlook the Press 20 Conference on Innovation 15 8 Golden Jubilee and Disruption celebrations in the offing; expansion plans unveiled Business Seminar at Cairo by the Embassy of India in Cabot Sanmar’s fumed Egypt silica expansion at Mettur 10 PS Jayaraman a main 25 21 speaker KCP Platinum Jubilee Visit of CII Indian 12 N Sankar recalls Sanmar- Delegation to Cairo KCP family ties Students from Odense, Chemplast organises Denmark in India on a 22 mega medical camps for 14 study tour rural populace Annual Day and Sports Nordic Ambassadors to Chemplast provides Meet at Madhuram India on a week-long financial aid for education 25 Narayanan Centre for 15 tour of Tamil Nadu and 23 and environment upkeep Exceptional Children Puducherry Legends from the South Indian Space Research Donation to Ellen Organisation: Sharma School, 26 Swati Tirunal 16 Pride of Modern India 24 Karapakkam (1813 - 1846) Matrix can be viewed at www.sanmargroup.com Designed and edited by Kalamkriya Limited, 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086.