An Imminent Clash As Experienced by Three Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

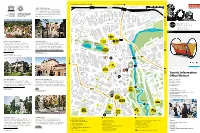

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Galerie Thomas Spring 2021

SPRING 20 21 GALERIE THOMAS All works are for sale. Prices upon requesT. We refer To our sales and delivery condiTions. Dimensions: heighT by widTh by depTh. © Galerie Thomas 20 21 © VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21: Josef Albers, Hans Arp, STephan Balkenhol, Marc Chagall, Serge Charchoune, Tony Cragg, Jim Dine, OTTo Dix, Max ErnsT, HelmuT Federle, GünTher Förg, Sam Francis, RupprechT Geiger, GünTer Haese, Paul Jenkins, Yves Klein, Wifredo Lam, Fernand Léger, Roy LichTensTein, Markus LüperTz, Adolf LuTher, Marino Marini, François MorelleT, Gabriele MünTer, Louise Nevelson, Hermann NiTsch, Georg Karl Pfahler, Jaume Plensa, Serge Poliakoff, RoberT Rauschenberg, George Rickey, MarTin Spengler, GünTher Uecker, VicTor Vasarely, Bernd Zimmer © Fernando BoTero, 20 21 © Lucio FonTana by SIAE / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © PeTer Halley, 20 21 © Nachlass Erich Heckel, Hemmenhofen 20 21 © Rebecca Horn / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Nachlass Jörg Immendorff 20 21 © Anselm Kiefer 20 21 © Successió Miró / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Nay – ElisabeTh Nay-Scheibler, Cologne / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © STifTung Seebüll Ada und Emil Nolde 20 21 © Nam June Paik EsTaTe 20 21 © PechsTein – Hamburg/Tökendorf / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © The EsTaTe of Sigmar Polke, Cologne / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Marc Quinn 20 21 © Ulrich Rückriem 20 21 © Succession Picasso / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © Simon SchuberT 20 21 © The George and Helen Segal FoundaTion / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 © KaTja STrunz 2021 © The Andy Warhol FoundaTion for The Visual ArTs, Inc. / ArTisTs RighTs SocieTy (ARS), New York 20 21 © The EsTaTe of Tom Wesselmann / VG Bild-KunsT, Bonn 20 21 All oTher works: The arTisTs, Their esTaTes or foundaTions cover: ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY PorTraiT of a Girl KEES VAN DONGEN oil on cardboard, painTed on boTh sides – Farmhouse Garden, p. -

The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 Denali Elizabeth Kemper CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/661 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 By Denali Elizabeth Kemper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis sponsor: January 5, 2021____ Emily Braun_________________________ Date Signature January 5, 2021____ Joachim Pissarro______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents Acronyms i List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Points of Reckoning 14 Chapter 2: The Generational Shift 41 Chapter 3: The Return of the Repressed 63 Chapter 4: The Power of Nazi Images 74 Bibliography 93 Illustrations 101 i Acronyms CCP = Central Collecting Points FRG = Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany GDK = Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) GDR = German Democratic Republic, East Germany HDK = Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) MFAA = Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program NSDAP = Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s or Nazi Party) SS = Schutzstaffel, a former paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany ii List of Illustrations Figure 1: Anonymous photographer. -

Berger ENG Einseitig Künstlerisch

„One-sidedly Artistic“ Georg Kolbe in the Nazi Era By Ursel Berger 0 One of the most discussed topics concerning Georg Kolbe involves his work and his stance during the Nazi era. These questions have also been at the core of all my research on Kolbe and I have frequently dealt with them in a variety of publications 1 and lectures. Kolbe’s early work and his artistic output from the nineteen twenties are admired and respected. Today, however, a widely held position asserts that his later works lack their innovative power. This view, which I also ascribe to, was not held by most of Kolbe’s contemporaries. In order to comprehend the position of this sculptor as well as his overall historical legacy, it is necessary, indeed crucial, to examine his œuvre from the Nazi era. It is an issue that also extends over and beyond the scope of a single artistic existence and poses the overriding question concerning the role of the artist in a dictatorship. Georg Kolbe was born in 1877 and died in 1947. He lived through 70 years of German history, a time characterized by the gravest of political developments, catastrophes and turning points. He grew up in the German Empire, celebrating his first artistic successes around 1910. While still quite young, he was active (with an artistic mission) in World War I. He enjoyed his greatest successes in the Weimar Republic, especially in the latter half of the nineteen twenties—between hyperinflation and the Great Depression. He was 56 years old when the Nazis came to power in 1933 and 68 years old when World War II ended in 1945. -

Irrational / Rational Production-Surrealism Vs The

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D/CI) Spring 2012 Professor Caroline A. Jones Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section. Department of Architecture Lecture 14 PRODUCTION AND (COMMODITY) FETISH: key dates: Lecture 14: Irrational Rational Production: Bauhaus 1919 (Sur)realism vs. the Bauhaus Idea Surrealism 1924 “The ultimate, if distant, objective of the Bauhaus is the Einheitskunstwerk- the great building in which there will be no boundary between monumental and decorative art.” -Walter Gropius (Bauhaus Manifesto. 1919) “Little by little the contradictory signs of servitude and revolt reveal themselves in all things.” - the Surrealist. Georges Bataille, 1929 “Bauhaus is the name of an artistic inspiration.” - Asger Jom, writing to Max Bill, 1954. “Bauhaus is not the name of an artistic inspiration, but the meaning of a movement that represents a well-defined doctrine.” -Bill to Jorn. 1954 “If Bauhaus is not the name of an artistic inspiration. it is the name of a doctrine without inspiration - that is to say. dead.'” - Jom 's riposte. 1954 “Issues of surrealist heterogeneity will be resolved around the semiological functions of photography rather than the formal properties … of style.” -Rosalind Krauss, 1981 I. Review: Duchamp, Readymade as fetish? Fountain by “R. Mutt,” 1917 II. Rational Production: the Bauhaus, 1919 - 1933 A. What's in a name? (Bauhaus” was a neologism coined by its founder, Walter Gropius, after medieval “Bauhütte”) The prehistory of Reform. B. Walter Gropius's goal: “to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftstnan and artist. [...] painting and sculpture rising to heaven out of the hands of a million craftsmen, the crystal symbol of the new faith of the future.” C. -

The Creative Output of Alexej Von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864

The creative output of Alexej von Jawlensky (Torzhok, Russia, 1864 - Wiesbaden, Germany, 1941) is dened by a simultaneously visual and spiritual quest which took the form of a recurring, almost ritual insistence on a limited number of pictorial motifs. In his memoirs the artist recalled two events which would be crucial for this subsequent evolution. The rst was the impression made on him as a child when he saw an icon of the Virgin’s face reveled to the faithful in an Orthodox church that he attended with his family. The second was his rst visit to an exhibition of paintings in Moscow in 1880: “It was the rst time in my life that I saw paintings and I was touched by grace, like the Apostle Paul at the moment of his conversion. My life was totally transformed by this. Since that day art has been my only passion, my sancta sanctorum, and I have devoted myself to it body and soul.” Following initial studies in art in Saint Petersburg, Jawlensky lived and worked in Germany for most of his life with some periods in Switzerland. His arrival in Munich in 1896 brought him closer contacts with the new, avant-garde trends while his exceptional abilities in the free use of colour allowed him to achieve a unique synthesis of Fauvism and Expressionism in a short space of time. In 1909 Jawlensky, his friend Kandinsky and others co-founded the New Association of Artists in Munich, a group that would decisively inuence the history of modern art. Jawlensky also participated in the activities of Der Blaue Reiter [the Blue Rider], one of the fundamental collectives for the formulation of the Expressionist language and abstraction. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Matters of Life and Death, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Hyman Bloo

HYMAN BLOOM Born Brunoviski, Latvia, 1913 Died 2009 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Hyman Bloom American Master, Alexandre Gallery, New York 2013 Alpha Gallery, Boston Massachusetts Hyman Bloom Paintings: 1940 – 2005, White Box, New York 2006 Hyman Bloom: A Spiritual Embrace, The Danforth Museum, Framingham, Massachusetts. Travels to Yeshiva University, New York in 2009. 2002 Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom, The National Academy of Design, New York 2001 Hyman Bloom: The Lubec Woods, Bates College, Museum of Art. Traveled to Olin Arts Center, Lewiston Maine. 1996 The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: Sixty Years of Painting and Drawing, Fuller Museum, Brockton, Massachusetts 1992 Hyman Bloom: Paintings and Drawings, The Art Gallery, University of New Hampshire, Durham 1990 Hyman Bloom: “Overview” 1940-1990, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1989 Hyman Bloom Paintings, St. Botolph Club, Boston 1983 Hyman Bloom: Recent Paintings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1975 Hyman Bloom: Recent Paintings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1972 Hyman Bloom Drawings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1971 Hyman Bloom Drawings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1968 The Drawings of Hyman Bloom, University of Connecticut of Museum of Art, Storrs. Travels to the San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Boston University School of Fine and Applied Arts Gallery, Boston. 1965 Hyman Bloom Landscape Drawings 1962-1964, Swetzoff Gallery, Boston 1957 Drawings by Hyman Bloom, Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH. Travels to The Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design; and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT Hyman Bloom Drawings, Swetzoff Gallery, Boston 1954 Hyman Bloom, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. -

Die Brücke Der Blaue Reiter Expressionists

THE SAVAGES OF GERMANY DIE BRÜCKE DER BLAUE REITER EXPRESSIONISTS 22.09.2017– 14.01.2018 The exhibition The Savages of Germany. Die Brücke and Der DIE BRÜCKE (“The Bridge” in English) was a German artistic group founded in Blaue Reiter Expressionists offers a unique chance to view the most outstanding works of art of two pivotal art groups of 1905 in Dresden. The artists of Die Brücke abandoned visual impressions and the early 20th century. Through the oeuvre of Ernst Ludwig idyllic subject matter (typical of impressionism), wishing to describe the human Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Alexej von Jawlensky and others, the exhibition inner world, full of controversies, fears and hopes. Colours in their paintings tend focuses on the innovations introduced to the art scene by to be contrastive and intense, the shapes deformed, and the details enlarged. expressionists. Expressionists dedicated themselves to the Besides the various scenes of city life, another common theme in Die Brücke’s study of major universal themes, such as the relationship between man and the universe, via various deeply personal oeuvre was scenery: when travelling through the countryside, the artists saw an artistic means. opportunity to depict man’s emotional states through nature. The group disbanded In addition to showing the works of the main authors of German expressionism, the exhibition attempts to shed light in 1913. on expressionism as an influential artistic movement of the early 20th century which left its imprint on the Estonian art DER BLAUE REITER (“The Blue Rider” in English) was another expressionist of the post-World War I era. -

Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture

AT UR8ANA-GHAMPAIGN ARCHITECTURE The person charging this material is responsible for .ts return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below '"" """"""'"9 "< "ooks are reason, ™racTo?,'l,°;'nary action and tor di,elpl(- may result in dismissal from To renew the ""'*'e™«y-University call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN I emp^rary American Painting and Sculpture University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1959 Contemporary American Painting and Scuipttfre ^ University of Illinois, Urbana March 1, through April 5, 195 9 Galleries, Architecture Building College of Fine and Applied Arts (c) 1959 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A4 8-34 i 75?. A^'-^ PDCEIMtBieiiRr C_>o/"T ^ APCMi.'rri'Ht CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE DAVID D. HENRY President of the University ALLEN S. WELLER Dean, College of Fine and Applied Arts Chairman, Festival of Contemporary Arts N. Britsky E. C. Rae W. F. Doolittlc H. A. Schultz EXHIBITION COMMITTEE D. E. Frith J. R. Shipley \'. Donovan, Chairman J. D. Hogan C. E. H. Bctts M. B. Martin P. W. Bornarth N. McFarland G. R. Bradshaw D. C. Miller C. W. Briggs R. Perlman L. R. Chesney L. H. Price STAFF COMMITTEE MEMBERS E. F. DeSoto J. W. Raushenbergcr C. A. Dietemann D. C. Robertson G. \. Foster F. J. Roos C. R. Heldt C. W. Sanders R. Huggins M. A. Sprague R. E. Huh R. A. von Neumann B. M. Jarkson L. M. Woodroofe R. Youngman J. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement.